In response to:

The Cold War Revisited from the October 25, 1979 issue

To the Editors:

In his review-essay on the Cold War (NYR, October 25), Arthur Schlesinger states several times—mistakenly—that Charles Bohlen and George Kennan shared the same unorthodox view of the Soviet Union, and therefore neither of them had any influence on American policy during the 1950s. Kennan and Bohlen, he says, felt that “Soviet policy may have sprung neither from revolutionary ideology nor from traditional Realpolitik but rather from the requirements of a ruling class determined to maintain itself in power”—a summary which ignores the fundamental difference between those two diplomats.

Kennan believes that Soviet leaders are a ruling class largely motivated by the goals and fears of a nineteenth-century country: except for nuclear and naval arms, “the outside world, and particularly the United States, would have little more to fear from Russia today than it did in 1910.” In contrast, Bohlen saw them as a ruling class very strongly motivated by ideology—saying in 1973, “For the United States, the ideological element of Soviet policy is of vital importance. It means that there can be no harmonious relations with Moscow in the customary sense of the word.” And Bohlen concludes, “The only hope, and this is a fairly thin one, is that at some point the Soviet Union will begin to act like a country rather than a cause.” Partly because of this difference, Kennan quit the Kennedy administration and had no influence in the Eisenhower years. Bohlen, on the other hand, held important posts all through this period except during the two years after 1956, when he was replaced in Moscow by an ambassador with similar views, Llewellyn Thompson.

Professor Schlesinger’s own interpretation of Soviet motives seems closer to that of Kennan, though it is hard to tell from his ambiguous summary. Surely an insecure ruling elite can be motivated by traditional concerns or by Bolshevik ideology—and in either case it can use Realpolitik as an instrument of policy.

John Taft

Washington, DC

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. replies:

Mr. Taft misreads my piece. I did not say that Bohlen and Kennan held identical views about the Soviet Union. I said that they both believed that the Soviet Union had legitimate security interests and that both rejected the so-called Riga axioms. They diverged on a number of points, but the distinction drawn between their views in the Taft letter is far too rigid. While Kennan on occasion emphasized the historical element and Bohlen the ideological element in Soviet policy, neither excluded the other element. It is not, as Taft implies in his last paragraph, an either-or situation. Obviously both elements helped shape Soviet international behavior.

I take it that, in the next to last sentence of his second paragraph, Taft means the Truman administration, not the Kennedy administration. Kennan left the Kennedy administration, not out of disagreement over Soviet policy, but out of a sense of futility over congressional intervention in US relations with Yugoslavia. Nor is it correct to suggest that Bohlen had influence in the Eisenhower years. In his memoirs, Bohlen describes how John Foster Dulles forced his removal from his post as ambassador to the Soviet Union. Bohlen adds: “He did not want me in Washington, because he would have to put me in a policymaking job” (Witness to History, p. 442).

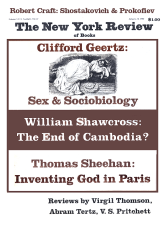

This Issue

January 24, 1980