In The Art of Love (1975) Kenneth Koch said that some poets like to save up for their poems, others like to spend incessantly what they have. Spendthrift is better than thrift, according to Koch, because the pocket is bottomless, “your feelings are changing every instant,” and the available combinations of language are endless. In practice, as in the practice of The Art of Love, the big spenders write on the assumption that if you shoot a lot of lines, some of them are bound to hit the mark. If you feel inclined to out-Byron the Byron of Don Juan, you can write a long poem like Koch’s The Duplications (1977), keeping the stanzas going with a little plot and a lot of virtuosity, rhyming Hellas with fellas, and so forth.

Virtuosity takes verve. Koch’s poems are attractive not because they draw us into the charming circle of their rhetoric but because they “so serenely disdain” to edify us: they maintain power by rarely choosing to exert it. When they fail to be attractive, it is not because they take themselves too seriously but because they presume upon their grace and leave it compromised.

The Burning Mystery of Anna in 1951 is a new collection of ten fairly long poems, written in a loping, phrasal style, casual in its connectives if careful enough in its general direction. The poems have sturdy themes (anxiety; light and shadow; love; loss), but the themes are not taken as if they stood waiting to be glossed, explored, and understood. They are not even means to an end: rather, means of discovery, pursued not in the hope that they will lead to an end but that they will postpone every proffered end, endlessly. In “The Language of Shadows” Koch writes that

…Everything’s extinguished in desire

In fact and action

and he wants to fend off extinction by postponing fact and action, lest desire, too, die. The method is revery rather than argument or summary. It is what Wallace Stevens meant by “the hum of thoughts evaded in the mind”; evaded, presumably, so that thinking may persist.

Not themes, then, but talk, an aesthetic of talk, as in The Art of Love and one of the new poems, “The Problem of Anxiety,” where desultoriness gives the poet’s mind room to move and whatever time it needs to say something helpful to somebody. Nearly any theme will do. “One sidewalk leads everywhere, you don’t have to be in Estapan.” Koch likes to come upon things when they are just about to happen; like water about to boil, the telephone about to ring. Sarajevo an hour before the event. More interested in Sarajevo than in its cause, he likes to pick up a theme the first moment it becomes available and give it an unofficial future according to his revery.

The risk is that revery becomes whim or some other form of self-indulgence. Koch is not immune to this vanity. Like nearly every other poet of the so-called New York School, he has produced yet again the usual garrulous dribble about what it was like, back in 1951, to rap with Frank and Larry and John and Jane on West 10th Street:

…Larry sat on the stairs

And John said Um hum and hum and hum I

Don’t remember the words Frank said Un hun

Jane said An han and Larry if he

Was there said Boobledyboop so always

Said Larry or almost and I said

Aix-en-Provence me new sense of

These that London Firenze Florence

Now Greece and un hun um hum an

Han boop Soon I was at Larry’s

And he’s proposing we take a

House in Eastham….

James said we must concede to the artist his donnée, and so we must, but this particular donnée has been done to a self-regarding turn so often that I hope it has now been done to death.

The superb poems in The Burning Mystery of Anna in 1951 are “In the Morning,” “The Boiling Water,” and “To Marina,” each not only good but virtuous in the sense described in The Art of Love as

excellence which does not harm

The material but ennobles and refines it.

“To Marina” ends the book, heart-breakingly, and tells why the kissing had to stop and why the love could not stop. The aesthetic of talk hates to stop talking, but sometimes it must, and “To Marina” is a love poem desolate in its conclusion:

…I am over fifty years old and there’s no you—

And no me, either, not as I was then,

When it was the Renaissance

Filtered through my nerves and weakness

Of nineteen fifty-four or fifty-three,

When I had you to write to, when I could see you

And it could change.

“In the Morning” and “The Boiling Water” are nearly as good, nearly as virtuous with the civility of good talk, but they do not bring one, as “To Marina” does, close to tears.

Advertisement

James Schuyler and Kenneth Koch practice many similar themes, but the phrasing is different, the fingering. What they mainly practice is reluctance to allow a desire to settle for its premature resolution in a thought.

The Morning of the Poem is in three sections: fourteen new poems, quite short; the “Payne Whitney Poems,” eleven drastic reports from a psychiatric hospital; and the title poem, sixty pages long, a verse-letter to a friend, a painter. In the short poems the themes are variants of change and repetition:

Discontinuity

in all we see and are:

the same, yet change,

change, change.

Change is felt mostly as loss: lost love, lost lovers. But Schuyler’s stress is on survival: look, he has come through. He thinks it a miracle that anything exists and has surmounted the forces all set to destroy it; not least, himself:

…When I think

of that, that at

only fifty-one I,

Jim the Jerk, am

still alive and breathing

deeply, that I think

is a miracle.

Poetry consists in reporting the miracle that things are what they are, that at the poet’s elbow there is a wicker table, that the fields beyond the feeding sparrows are brown

yet with an inward glow

like that of someone of a frank good nature

whom you trust.

Schuyler’s favorite mood is the indicative, he loves to say that something is the case. If time is the category of loss, there is always place. Places make up for times, as a garden, for instance, lets you feel that the past is no longer a burden. Schuyler writes glowingly of gardens, and allows one to think that botany is the most majestic science.

I hope I have not made Schuyler sound like a pastoralist, thrilled to discover that seeds become flowers. His poems don’t resort to the natural world as to an Eden: they never call upon Nature to rebuke Culture. In fact, his language tells the other story, not that Nature is our lost Paradise but that human feeling provides the “fiction of accord”—I take the phrase from Frank Kermode—in which Nature and Culture are reconciled. I go further to remark that in Schuyler’s poems the natural world is drawn into complicity with Culture, as if horticulture, for instance, testified to our best way of being in the world. Schuyler writes of landscapes as if they were landscape paintings, which they are, if certain epistemologists are right. Snowflakes in one poem are compared to torn bits of paper; a man seen through snow is compared to an exclamation point; a sky to a swimming pool. In “The Morning of the Poem” lilies are said to “bloom with their foxy adolescent girl smell.” Leaves of trees move

…like fingers improvising on a keyboard

Scriabin in his softest mood, and the wind rises and it all goes Delius.

The racing water of Cazenovia Creek is “a tossed-out length of coffee-colored satin.” A road in rain shines “slick as though greased with Vaseline.” In an earlier poem from Schuyler’s The Home Book (1977) “the sky’s orangerie slushes coffee ice.” I read these gestures as Schuyler’s way of eluding alienation; by assimilating nature to culture, he can make bridges instead of burning them. And I find no irony whatever in a produced shopping list, again in “The Morning of the Poem,” which goes from Bread (Arnold sandwich) and Taster’s Choice to Noxzema medicated shave foam, Baume Bengué, and K-Y. Schuyler is one of the few poets who write with equally unembarrassed respect of coffee beans and Folger’s Coffee Crystals. And who else has written of shampoo and rain without offense to either?

Rain! this morning I liked it more than sun, if I were younger I would have

Run out naked in it, my hair full of Prell, chilled and loving it, cleansed,

Refreshed, at one with quince and apple trees.

“The Morning of the Poem” is a long autobiographical poem. If it were a film, it would get a PG rating and might be entered for the Gay Film Festival. Its method is the free fall of recollection, its morality the poet’s conviction that whatever his feeling touches is absolutely privileged:

the truth, the absolute

Of feeling, of knowing what you know, that is the poem.

So the poem traverses sundry lovers, a poison-suicide in Virginia, certain roses, nephew Mike, syphilis, a performance of Springtime for Henry, Diaghilev’s tomb, a whippet, Joyce’s Ulysses, Fairfield Porter, John Ashbery, Edwin and George and Donald and Roy, the Catholic understanding of sin, watching the Olympics on TV, Ned Rorem, and a problem of urination in Paris. Themes are evidently not as important as the grace of being among them. Schuyler’s language is not always alive. I was surprised to find him reporting that an Olympic diver “cut the water like the blade of a knife.” But the poem is wonderfully vivid, like Vermont in January, Schuyler’s place and time, and I renew my faith in miracles when I find Schuyler surviving his resort to themes I have some difficulty in not regarding as disgraceful.

Advertisement

Frederick Seidel has long been saving up for Sunrise, a collection of thirty-one short or fairly short poems, one of them reprinted from his earlier book Final Solutions (1963) as if to indicate that the way to perfection does not necessarily run, as Pater thought it did, through a sequence of disgusts. Seidel is still loyal to his first book, as well he may be. Even then he had a gift of style, though in some poems it seemed mostly a gift of Robert Lowell’s style:

Once, his nerves would have stood and stared, prongs on a mace,

His meatless Jansenist hooked face….

The first poem in Final Solutions, “Wanting to Live in Harlem,” was also the best, so it is good to find it taken up again for Sunrise, where it may be read beside other poems just as good.

Many of Seidel’s new poems are on public themes: Robert Kennedy, Antonioni filming Zabriskie Point in Arizona, Francis Bacon and bohemian life in London, Elaine of restaurant fame, the Marquis de Sade, Dean Rusk, Vietnam, the New Frontier, certain famous motorcyclists. The poems are all formidably inventive, and some of them are as moving as their themes suggest they should be. But I am not always as sure as I would like to be that Seidel has distinguished between face value and true value. He writes of motorcyclists with a certain metallic sheen more appropriate to their vehicles. I found it hard to take the poem about Antonioni seriously, since I recall Zabriskie Point as a vain and bloated film. I don’t need to be persuaded that Robert Kennedy was in some respects heroic, but was it really possible, even in RFK’s America, to “love politics for its mind”? Some of Seidel’s poems are insecure in their attitudes. A remarkably gifted and serious poet, he gives me the impression, in some poems, of having lost or given up his confidence in the official forms seriousness has been supposed to take. It may be significant that these poems were written during the years in which the word “sophisticated” gave up its severity to become a term of easily earned praise, and the word “style” gave up its depth to become surface.

Despite that, Sunrise is an even stronger book than Final Solutions. Seidel’s voice is now securely his own. Lowell and Yeats are incorporated so fully in his language that they are no longer present as separable excitements. Seidel is capable of metaphysical conceits, but they are his own, as in the first line of “Sunrise.” “The gold watch that retired free will was constant dawn.” How appropriate to begin a long poem with the sun, seen for a moment as token of retirement, but with its own version of constancy and new life! Later in the same poem there are passages which virtually allude to Lowell, but only by showing for the moment an equal mastery of a certain tone:

O Israel! O Egypt!

The enemy’s godless campfire at night, meat roasting

As you breathed near, sword drawn. Cut. Juice that dripped—

Later—from the dates from the hand of your daughter

Placed on your tongue in joy. Salute the slaughter.

This, too, is from “Sunrise,” the longest and most powerful poem in the book, an intensely personal poem arising from an appalling accident that happened to a friend. In forty stanzas the disaster is pondered, not to take it out of sight or out of mind but to make it in some sense bearable, involved with other events, not all disasters. The watch becomes “watch he has no use for now, goodbye,” and the poem, like the poet, goes through an elaborate circuit, diversion to several foreign cities and reflections, ending still in rage. The disaster is borne, which does not mean that it is bearable.

“Sunrise” is the most powerful, but “The Soul Mate” is the most beautiful poem in the book, a love poem as touching as anything I have read in years.

Trader is Robert Mazzocco’s first book of poems, and already he has his theme. Many of the poems are desperate colloquies about sameness and difference, as between two people, brothers it may be, who have come to know such things the hard way. Sameness and difference provide Mazzocco with his persistent trope as he writes about the past one repeats in dreams, shadows waiting for the light to create them, the ghost that never changes:

The ghost of the owner

The spirit of the father

Slowly entering the mirror the chair.

Imagine expecting two things to be different, only to discover that they are the same:

The spaces of night the remembered steps

The torn and the whole

Are one and the same the branches of loss

The branches of fullness the sycamore

And summer blood the hunger

That turns us from death to breath and back.

Such poems are “hymns against the volcano.”

Mazzocco’s special feeling is dread, italicized by the menacingly exotic setting in which it is met. Some forms of it come as if from myths, terrible anecdotes of suffering that have never accepted the companionship of being civic or historical. These truths exist not at one remove but at one refusal, they refuse to be assimilated to our cultural processes and models. Moral lessons are recited by powers to which (to whom) we have not conceded the privilege of such ministry:

The bent grass whispering

It’s right it had to be

Gradually, the whole book becomes suffused with the light in which things recede from their appearances: it ends with a poem in which Van Gogh writes to his brother Theo:

There are mountains everywhere

He said but no shrinesIf I lose my self

My self does not lose me…

As a collection, Trader is rather unvaried. Mazzocco writes all-out, but mostly all-out in one direction, intimations of dread. I would like to find in the book a few poems in which the mind would lay by its trouble and relent; that, it appears, must be sought in the next. But he has made a most impressive start.

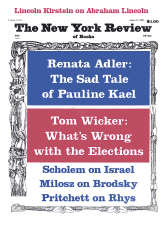

This Issue

August 14, 1980