PROVINCETOWN 1932

—On rainy days and in dreary winter weather you felt cooped up on the narrow land,…like all places where life is so much the water.—A sailboat slipping by at night refreshing the night by a tracing of silent life across it—the dark church of Truro set high on its hill on one side of the harbor and white Long Point light at the end of its sand-spit on the other.

—pack of German police dogs on the sand flats

—children in kayaks like water bugs

—Sunset: the oystershell harbor—the water roughened and shell-blue, the Long Point lighthouse and the building behind clear white like bits of shell—then a sail and the lighthouse sharp white on a uniform dim pink-gray of sea and sky, the sea now smooth—then the sea delicate pink over blue, silken, the sky a baby blue at the horizon that deepens toward smoke-blue of night and above it a layer of cloud a slightly brighter pink than that of the water—the sailboat and the houses on the point came out suddenly, it seemed, clear yellow as the color of the sun struck them—then a pink pale ruby came out in the lighthouse.

CHICAGO 1932

Unemployed. In schools, factories, warehouses, old jails—whitewashed furniture—factory walls, yellow school walls soiled, blackboards punched through, thin blankets and a sheet, men in holey socks and slit union suits, tattooed with fancy designs and with the emblems of services they no longer served, with fallen arches taken out of their flattened shoes and done up with bandages of adhesive tape, or lying wrapped up in their blankets on their backs, their skin stretched tight over their cheekbones and jawbones almost like the faces of the dead—the smell, peppery-sweetish stink: sulphur fumigations, cooking food, sweat, creosote disinfecting, urinals, one element or the other figuring more prominently from time to time but in the same inescapable fumes of humanity not living and functioning naturally but dying on its feet and being preserved as best one could, venereal disease, Negroes with t.b., lonely as a pet coon, men poisoned with wood alcohol—fifteen cents a pint—two sick and one to the psych hospital—benzine, kerosene, and milk—I say, which will you have, your bottle or a bed?—and they won’t give up the bottle—I wouldn’t be surprised if a hearse drove up and a dead man got up and walked out and asked for a flop—a cripple drunk again—one man so lousy no one would go nearum and they puttum in the stable with the horse and the horse tried to get away and then the next morning they gaveum a shower and scrubbedum with a long-handled brush.—They fumigate the clothes and if they’re moist it ruins them.

Chicago is probably doing as good a job as anybody.—Entertainments so that they won’t hold meetings and get ideas of revolt—the recreation hall (Hoover Hotel), thick with smoke, men sitting on the steps of the platform and flopping on the floor, newspapers lying around, people sitting in the gallery waiting for the show to begin (Thurston the magician, Tarzan, prize fights in gyms)—honest, good, and capable faces—the floors covered with spit—don’t let them into the dormitories till five—humanity being reduced to the grayness or rather the colorlessness of the monotonous streets—lice “crumbs,” bedbugs, spinal meningitis, nine cases—the Salvation Army excludes drunkards—razor frays in the basement down with the urinals where the bad characters are sent and the newcomers have to go when there’s no room for them yet up above—obscure shootings—less since the four-dollar-a-week arrangement—men who run shelters are afraid of losing their jobs, insist that four dollars come back, there’s no use in giving them that, they’re worthless—old men in showers with thin arms, flat chests, and round bellies—humanity reduced to the primal neutral undifferentiated grayness, even the human glow of life which marks life off from its background extinguished—mess men and officials right out of the line—blue shirts, loose ties, no ties—food—slum, clanking of trays, dumping what was left in GI cans like the army—coughing and colds in the infirmary—a few cuts of meat, the cattle and pigs at the packing houses being killed and cured to feed people—white-collar men with phones in relief offices—tailor shops in basement—playing cards—library—

basements in most shelters only available places for lounging—“bull pens”—

Christian Industrial Union. The Blood of God Can Make the Vilest Clean—Jesus the Light of the World—same smell—men lying with one hand behind their heads or with the sheets pulled up over their faces—the old yellow oak woodwork and scraped walls of the courthouse—GI can for slops in the mess hall—only two meals a day—fat men, old thin men, men of all nationalities—Communist meetings, entertainers—blue shirts—men pillowed on newspapers—army cots—two tiers of bunks—wooden benches that they slept on with coats—old Cicero policeman who had been saved, they routed them to mess through the prayer-meeting hall so they’d be exposed to religion on the way, prefaced it with waltz to get people to come—people in infirmaries for starvation: weakness, exhaustion, bad kidneys, sores—four of the meningitis cases had tied themselves up in knots and died—sitting under dark bridges—The Shadows.

Advertisement

—the stagnant smell of humanity

On Harrison Street. The snow, big dull dark square industrial buildings around it—blackened weeds old springs, picked bones of old cars and black old metallic junk unsalvageable even for the scaly-scabrous-looking huts that have fastened to the vacant lot like barnacles, made out of old tar paper and tin, with stovepipes all slightly crooked and buttresses of packing boxes—people who can’t stand for the shelters—a pole flying a black torn rag, the flag of despair.

“a sense of lost personality—quiet and despair”—“fear”

—young men coming of age during workless period—forced out of their respectable wage-earning class into casual status, associate with confirmed casuals, get discouraged about idea of working

—the abyss of grayness and death—the neutral, the nonhuman, an undifferentiated plasm that is less than human and then nothing

NEW YORK 1932 AND 1933

Scott and Hemingway. Scott fixed me with basilisk stare the moment I came into the room—he had still never been able to get over my having been three years ahead of him at Princeton—wouldn’t talk and wouldn’t let us talk.—What happened to you? he asked me—Where’s Mary Blair?—Hemingway took a victoria to the Aurora restaurant because he wanted to do something for the horse—to make it up to them for bullfights—Scott with his head down on the table between us like the dormouse at the Mad Tea Party—lay down on floor, went to can and puked—alternately made us hold his hand and asked us whether we liked him and insulted us—told him he was a good writer—complimented him on story in Mercury, “Absolution,” and asked him whether it was part of a novel, and he answered, None of your business.—Said at first he was looking for a woman—Hemingway said he was in no condition for a woman—then that he was done with men—perhaps he was really a fairy—Hemingway said they used to kid like that but not to overdo it.—Hemingway said, We’ll have to be careful because some of the best kids are so darn close to insults!—but he lectured him on his overhead—had to cut it down now, but he could have cut it down in Paris and had been so proud of his overhead!—Scott would say to me of Hemingway, Don’t you think he’s a strong personality?

—At the Plaza, I stayed behind after Hemingway left, thinking Scott might open up, but he simply took off his coat, vest, pants, and shoes and put himself to bed and lay looking at me with his expressionless birdlike eyes.—I had asked him what he did in Baltimore—he replied truculently, The usual things!—I said I’d heard the theory advanced (by Dos Passos) that he was never really drunk but used the pretense of drunkenness as a screen to retire behind—this only made him worse if anything in order to prove that he was really drunk—though his answers to questions and remarks suggested he was in pretty good possession of his faculties.

—Hemingway told him he oughtn’t to let Zelda’s psychoanalysis ball him up about himself—he was yellow if he didn’t write.—It was a good thing to publish a lousy book once in a while.—Hemingway sang a little Italian song about General Cadorna to the waiter.—Next morning Scott called me up and apologized for things he had said which might have wounded me and called Hemingway up and asked him to repeat something he’d said.—I remarked on the cold eye Scott had fixed me with when I’d first come in—He said, No confidence, eh? Well, you’ll have to learn to take it.—He’d also said apropos of nothing, Shall I hit him?

When Scott was lying in the corner on the floor, Hemingway said, Scott thinks that his penis is too small. (John Bishop had told me this and said that Scott was in the habit of making this assertion to anybody he met—to the lady who sat next to him at dinner and who might be meeting him for the first time.) I explained to him, Hemingway continued, that it only seemed to him small because he looked at it from above. You have to look at it in a mirror. (I did not understand this.)—It seemed to me that ideas of impotence were very much in people’s minds at this period—on account of the Depression, I think, the difficulty of getting things going. I had one adventure myself when I was unable to get myself going. It was true that I had been drinking and that I had never before even kissed the woman, who was a fairly close friend but who did not enormously attract me. I have the impression that various kinds of irregular sexual ideas are feared or become fashionable at different times: incest, homosexuality, impotence.

Advertisement

* * *

[From a visit to the Fitzgeralds at their house in Towson, Maryland.] Zelda very cute in blue sweater that matched her eyes and light-brown riding breeches that matched her hair, subdued, a plaintive note in her voice and sometimes a sort of mumbling as of an old person who had lost her teeth—not drinking. Scott began by giving me a cocktail for lunch, not drinking himself—a little wine at meals, one glass to two of mine, a highball before dinner, and he would disappear from the conversation from time to time for a moment—finally gave Zelda a little thimbleful of wine—a little treat, honey, in honor of Bunny—the next day I didn’t drink and he was snitching them regularly—when I refused, he said, It seems so puritanical somehow, breaking off (entirely) like that!—he gave Zelda another little thimbleful of wine—when he put me on the train, he said he was having a hard time with Zelda because she’d begun stealing drinks.—The next morning he said at our noon breakfast: Drunkenness is an awful thing, isn’t it?

Mary Pickford at Sherry-Netherland. She was little and simply dressed—I was disconcerted at first by the effects of the horrible face-lifting process which she had had performed and which tightened the skin so over all the lower part of her face that she couldn’t smile with her mouth, which was nothing but a little stiff red-lined orifice in the face of a kind of mummy, nor change her expression at all. Only the upper part of her face was alive—the eyes, dark agatelike blue which glowed, even flashed, from time to time, with a slate-blue power of energy and will—and intelligent humor coming out in the brows—human and very attractive, while the lower part of her face remained immobile. Her profile was not good—nose common and not straight, somewhat recessive chin, accentuated no doubt by the shrinking of skin which suppressed her cheeks. What had been intended to make her look young for the public had the uncomfortable effect at close range of making her look old. Businesslike, practical, clear in her mind, fairly intelligent—an American small-town girl, probably Irish, who by dint of her peculiar position had become something of a woman of the world. I liked her.—It seemed to me that for a moment when she first came into the room, and for a moment when I was leaving, there was a little despiteful look—or was it the tightening of the skin around the mouth—as of resentment and disappointment against a world to which she was no longer irresistibly winning.

[Arthur Hopkins, who had read my play Beppo and Beth and who talked about producing it, had suggested that I might collaborate with her (Mary Pickford) on a play she wanted to write—I forget about what. She amused me by talking in movie terms—asking whether my “options” would leave me free.]

NEW YORK, 1937

Gausses. [Christian Gauss was the teacher for whom Wilson had the most respect at Princeton and they kept in touch. Axel’s Castle was dedicated to him.] It was just after Paddy Chapman’s death and the death of Gauss’s grandson, and they seemed much to have aged since I had seen them. Gauss had, besides, just had to have a tumor—which he said was not malignant—removed from the back of his head. After Coindreau (a little bright and appreciative, but probably not profound, coffee-colored Frenchman [whom Gauss had installed at Princeton]) and I had talked about André Gide’s recent assertion that he had ceased to write “from disgust,” Gauss said, later, that he felt the same way; and it seemed to me that it was true that he had less aim and direction than usual, but he was in a way not any less impressive: he gave somewhat the effect of a radio, which you shift from feature to feature.

There was the journey during the Middle Ages of a traveler from Rome to Avignon or Nîmes—he wouldn’t have any feeling of having entered a different country. This, at a turning of the little knob, would give way to the contemporary subject of mental disorders among the students—8 percent, he thought, needed the psychiatrist, and he told me about a boy who had threatened to saw off his companions’ heads but had afterwards gotten married and apparently worked out all right, of a boy who had thought he had worked out a prescription for the salvation of all mankind—Reconciliation Peace, mathematical formulas, etc.—and had gone down to Washington to get it patented—had thought people were after him to steal it from him and had sat up all night in the pay toilet of the station—Gauss described his adventures with the same precise imagination with which he had recounted the journey of the traveler from Rome to Nîmes—then the boy had attracted the attention of someone as he prowled around the capital in sneakers and was eventually sent back to college. Another boy was apparently a potential sex criminal, had attacked several women and finally a little colored girl.

Then he would shift to the question of “historicity,” greatly overemphasized nowadays—he thought; people devoted too much attention to dating things rather than appreciating their general importance. There was a man at Yale and there were others who “had a stake in” establishing the idea that there were more Giorgiones in existence than had previously been supposed (only sixteen), so they had moved up Titian’s birth twenty-five years in order to make it impossible for Giorgione to have studied in his studio (the old tradition was that Titian had died at ninety-nine), but Gauss thought that a face and certain other things in some of Giorgione’s pictures—he seemed to have them right before his eyes—had probably been painted by Titian. Or it would be Hutchins at the University of Chicago or contemporary French fiction or the Aoi that set off the stanzas in the Chanson de Roland.

I had never seen so clearly before how he lived in an intellectual world of which he was perfect master, which included many centuries and countries, the past and the immediate present, but where he wandered rather than worked, one thing leading to another, ideas leading to trains of thought which carried him without effort through the ages, but not giving rise to definite lines of inquiry or the establishment of definite principles on which he should act—like the physicist’s continuum of time and space—from which he never emerged, absent-minded about daily matters for all his grasp in such detail of the administrative affairs of the college—on the cold day, after putting on his coat, he started to go out without his hat. But it was what made him such a wonderful teacher—he seemed to have infinite learning, infinite range of interest, infinite intelligence and sympathy. He suggested all kinds of lines of thought, was always sprouting fresh ideas, which, though he himself never far developed them, provided leads for other people. And at the same time, in connection with his duties, he had succumbed to some of the stupidities of Princeton: signs of anti-Semitism; the knowing glance and smile which he and Nat Coindreau exchanged over the prejudice against Jews which they shared—many Jews seemed to love coming into the scientific side at Princeton, especially since the ascendancy of Hitler. Gauss seemed to have seen little of Einstein. Gauss said that in the teaching profession there was no criterion of competence, as in medicine or the bar. He gave as an example that some reactionary man in the History or Economics Department had a panacea for all the ills of society—as if I were supposed to draw the conclusion that this constituted an incompetence for which he ought to be fired.—When I asked Walter Hall about academic freedom, he replied: “You know what Conant says—if we want to preserve our academic freedom, we’ll have to watch our promotions.”

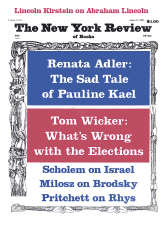

This Issue

August 14, 1980