To a chorus of political mudslinging and inflammatory editorials provided by Athens’s volatile daily press, Greece is moving toward a fall election between the two perennial elements of Hellenic society—the conservative-authoritarian and the demagogic-liberal. On the right, George Rallis, the incumbent premier, has been the leader of Constantine Karamanlis’s New Democracy party ever since Karamanlis himself was, by the narrowest of squeaks, elevated from the premiership to the presidency in 1979. As long ago as the summer of 1975 the opposition had predicted this move, if ever Karamanlis were to feel his political base threatened,1 and the prediction came true, with Rallis playing Pompidou to Karamanlis’s de Gaulle.

The candidate of the left, Andreas Papandreou, founder of the radical Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), former Berkeley economist, ideologically ambivalent, a master of public rhetoric, is regarded by many as a power-hungry political saltimbanque. He and Rallis are natural, almost archetypal opponents. Anyone with a sense of the Greek past will feel on familiar ground here. It is like the rivalry of Charilaos Trikoupis and Theodore Deliyannis, who for the last two decades of the nineteenth century alternated as leaders somewhat in the manner of Gladstone and Disraeli. The parallel, indeed, can be taken further. New Democracy’s economic program is historically reminiscent of Trikoupis’s methods, while Papandreou, like Deliyannis, certainly goes in for “demagogic exploitation of Greek irredentism.” 2 Earlier still one thinks of oligarchs against democrats, Cimon versus Ephialtes. Is this a scholar’s illusion, or does Greek political history really repeat itself to this degree?

The current scene certainly does tempt one to more or less plausible ancient parallels. In 1974, after the overnight collapse of Brigadier Ioannides’s totalitarian regime3—a result chiefly of the Cyprus debacle, in which a right-wing group working on loannides’s orders clumsily failed to assassinate Archbishop Makarios4—Karamanlis returned to Athens. He was, understandably, given a hero’s reception (joined by many quick-change artists who had hitherto backed the junta), and had an enormous bank of goodwill on which to draw for the immediate political future. This for the most part he used tolerantly and carefully, although the problems of the vast, polluted, overbuilt, and corrupt Athenian megalopolis remained intractable. Now, seven years later—the length of the Colonels’ repressive dictatorship—there are signs, not least after the elections of November 1977 (when New Democracy’s share of the vote fell from 54 to 42 percent), that the account may be close to overdrawn. Karamanlis, like Trikoupis, aimed for long-term economic development, primarily by getting Greece into the Common Market. Whether he was right or not remains to be seen; but short-term economic hardships and uncomfortable adjustments were as inevitable as they were predictable, and Papandreou has been making the most of them, wearing his economic hat when he does so.

In Greece more than most other places, political gratitude maintains its sense of favors to come. Karamanlis has escaped, as it were, by apotheosis: but Rallis may well be pondering the story Plutarch tells of how the young Themistocles, strolling with his father along the beach at Phaleron (where, with symbolic aptness, the main Athens sewer now discharges its ever-increasing load), was shown the salt-caked frame of an old, abandoned trireme: “That, my son,” said Neocles, “is how the Athenians treat their statesmen when they have no further use for them.” Like so many of the best Greek historical anecdotes, this one is probably apocryphal, but it contains an essential truth, as applicable today as two and a half millennia ago. In February 1945, the British made a deal with the Greeks, the so-called Varkiza agreement, after the communist attempt at a takeover in Athens had failed. ELAS, the National Popular Liberation Army, with official communist approval, agreed to the terms, which included the surrender of arms, and elections under Allied auspices. Many communists, and in particular Aris Veloukhiotis, the brilliant wartime guerrilla leader, regarded the Varkiza agreement as a betrayal. When Aris refused to surrender, he found himself denounced by his own former comrades, pursued by the national guard, and betrayed by villagers. Finally, in despair, he shot himself; his head was stuck up on a pole in Tríkkala outside party headquarters.5

One must also bear in mind how easily and quickly Greeks get bored, above all with virtuous public figures. St. Paul was neither the first nor the last visitor to Athens who noticed the passion for change and novelty dominating the local population. During one ostracism held about the time of the Persian Wars, an illiterate peasant, looking around for someone to scratch Aristides’ name on his voting sherd, happened to accost Aristides himself. When the latter, understandably, asked him (without revealing his identity) why he wanted Aristides ostracized, the peasant is said to have replied: “Because I’m sick and tired of hearing him called ‘The just.’ ” A similar attitude in the electorate could well hurt Rallis, who lacks Karamanlis’s personal appeal. As in the recent French elections, many people may simply feel it’s time for a change.

Advertisement

On the other hand, Papandreou’s unpredictability, rhetorical violence, and apparent opportunism have left many Greeks of varying political views deeply suspicious of him as a prospective prime minister. It was observed, for instance, that as soon as he felt he might actually be within reach of forming a government, he began to back off from his more extreme attacks against NATO, the EEC, and the US. This got him labeled a “water carrier” or “catspaw” of the right by KODESO, an alliance of communist splinter parties, the word for “catspaw,” ourá, being only a change of accent away from the common term meaning “piss.” “Andreas,” people told me in Athens last summer, “ah yes, he’s a splendid entertainer, keeps things lively, never a dull moment, great hand at getting students out on the streets. But to run the country, now…po po po, it’s not as though he was his father.”6 But PASOK is certainly the best organized of the present political parties, and commands a surprising degree of intellectual support: its propaganda, like its posters, comes in the brightest primary colors. For a foreigner one of its slogans, everywhere spraypainted on walls, has an impact that was certainly not intentional. “PASOK, the People’s Movement,” it proclaims. The word for “movement” (also, suggestively, the word for coup or Putsch) is kínema, and popular cinema is precisely what Andreas provides as he goes from rally to rally denouncing both the government and the communists. Whether that will be enough we shall see. Recent reports from Athens suggest that the communists may do better than expected, though such predictions are common enough around election time, and more often than not originate in party propaganda.

Though still deeply scarred by their political past, the Greeks seem doomed, like the Mycenaean House of Atreus, to work through a recurrent and self-perpetuating curse in the pursuit of their public destiny. Against this it might be argued that today two great differences exist between ancient and modern Greece, both making for a unity that the city-states could never achieve: the presence of the Greek Orthodox Church, and the fact of nationhood, painfully won for the first time in the early nineteenth century, to be defended with passionate patriotism thereafter. But have these unifying forces really made all that much difference? The political emergence of Hellas as a country has not abolished that chronic divisiveness with which Greece has been plagued since Solon’s day: it has merely shifted its terrain. “A nation of nine million political splinter groups” was one popular recent definition. The Greek war of independence during the 1820s left at least three rival factions competing for power, and during World War II the various partisan groups spent almost as much time fighting each other as they did the Germans.

As for the Orthodox Church, what it primarily took over, and reinforced, was that sense of cultural identity proclaimed by Herodotus (8.144), when he speaks of “our being of the same stock and the same speech, our common shrines of the gods and rituals, our similar customs.” Though its part in preserving this heritage under the Turkish occupation has sometimes been underestimated (Richard Clogg’s Short History of Modern Greece is a good case in point), it has also, at times, taken up some very odd positions. In 1798, for instance, the Patriarch Anthimos of Jerusalem argued that the Greeks “should remain loyal to their Ottoman masters, for the Ottoman Empire was in itself a creation of the Divine Will, raised up specifically to protect Orthodoxy from contamination by the heresy of Latin Catholicism.”7 To understand that attitude we need to look as far back as the Fourth Crusade, which ended, paradoxically, with the forces of Western Christendom sacking Christian Constantinople in 1204.

Looking for continuity can be a risky game. Several of the Colonels’ more populist agrarian measures, including the moratorium on peasant debts and the floating of easy agricultural loans, sounded, at the time, as though the new dictators had been taking tips from an old one, Pisistratus. In fact, Colonel Papadopoulos, who led the coup in 1967, was probably borrowing his policies from a far more recent autocrat, General John Metaxas, who ruled between 1936 and 1941.8 The Greek system of education, still heavily biased in favor of the classics, must have left its mark on both of them: Papadopoulos’s much-quoted, much-abused statement about Greece being a patient to be kept immobilized in plaster till fit to walk was simply an adaptation of an ancient commonplace.

But a great deal of this floating knowledge goes back less than two centuries. Apart from isolated efforts like that of Gemistus Plethon, 9 during the last century of Byzantine rule before the fall of Constantinople (1453), the classical heritage was only rediscovered, in any real sense, at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Worse, it was then forced on an often recalcitrant Greek public by foreign philhellenes and Westernizing intellectuals.

Advertisement

This grafting on to old Byzantine stock of what had become, in effect, alien cultural values and wholly unfamiliar forms of government not only set up grave social tensions, but was to condition the whole subsequent history of modern Greece. If continuity exists, and I think it does, it lies not in any obvious classical echoes picked up at school, but rather in a deep, temperamental identity of attitude that, for good or ill, emerges most plainly in conflict and stress—a condition about as endemic to Greece as its limestone landscape and indented coastline.

For most people the complex history of Greece between the fall of Rome (at latest) and the Greek war of independence (at earliest) is hazy. Until very recently there was some justification for such ignorance in a general dearth of books on the period. That is no longer the case. Dearth is rapidly turning into glut. One gap, however, has only now been filled. The extraordinary; and romantic, episode of the Latins in Greece, the period during which the French crusader and adventurer William de Villehardouin built the great Spartan keep of Mistra (1249), has not been generally treated in English since 1908, when William Miller published The Latins in the Levant.10 Now, however, we have Nicolas Cheetham’s Mediaeval Greece, the work of a scholar and former diplomat, and delightfully written. It is a richly informative book that revivifies the Frankish presence in the Peloponnese, capturing the strange, magical interlude when there were Dukes of Athens and Princes of Achaea,when Catalans and Venetians and Florentines roamed the islands and established their transient rule (which left so many permanent legacies behind).

This was a time when the Parthenon was a Christian cathedral, and the Greeks (known to the Franks as “grifons”), while despising their new overlords’ uncouth manners, sensed that the rule of the Villehardouins and de la Roches was likely to be more secure, more prosperous even, than what they had known before. It is easy to forget how long it had been since the heady days of freedom prior to Chaeronea in 338 BC, under how many masters—Macedonians, Romans, Byzantines, Franks, Turks—the Greeks contrived to keep their culture intact.

A fascinating study of this long process (minus the Latin incursion, which never reached the lonian coast) is provided by Clive Foss’s Ephesus After Antiquity, which traces the vicissitudes of this famous classical city through the Byzantine and Turkish era down to modern times. War, devastation, and the silting-up of a once-fine harbor all took their toll: the city was finally rescued only by the coming of the railroad and the boom in archaeology.

To impose some kind of perspective on this vast stretch of history requires clear thinking, and a special gift for selection and organization, all of which the British scholar Richard Clogg possesses in abundance. His Short History of Modern Greece at once takes its place as the standard textbook (and will, I suspect, be revised and updated at regular intervals). It offers a neat and compact précis of events from the sack of Constantinople by the Latins in 1204 down to the latter part of 1978, with Greece teetering on the brink of entering the Common Market. Clogg’s approach is brisk, liberal, and discreetly anticlerical. A certain shrillness of tone is noticeable as we approach the Colonels’ coup of 1967 (the treatment of recent events is much fuller than that of earlier periods), but by and large Clogg sets out the evidence as fairly as anyone could expect so soon afterward.

This book is an admirable introduction for beginners, who will learn much that they need to know, including the anti-Latin bias of Orthodoxy (and its genesis), balanced by the symbiotic relationship that developed between the Patriarchate and the Ottomans; and the interchangeable role of brigands (klephts) and local government-sponsored irregulars (armatoloi), which was to have interesting repercussions on later resistance movements.

Clogg writes vividly about the gallery of “cranks, do-gooders and out-and-out rogues” who helped to compound the rivalries and inefficiencies of the freedom fighters during the war of independence (the Turks, it has been suggested, lost the war rather than the Greeks winning it); and about the clash, then and during Greece’s subsequent independence, between the klephts in their foustanellas and the liberal civilians who dressed alafranga, i.e. Western style. The autocracy of Capodistrias (who held, understandably, that the bankrupt, anarchic Greece of 1828 was in no state for the divisive luxuries of democratic rule) led to that odd importation, a Bavarian monarch. Great Power meddling in Greece has seldom produced happy results.

As Clogg carries his story into modern times we find ourselves in increasingly familiar territory. Conspiracies by army officers (sometimes for liberal objectives, e.g. the 1844 constitution, sometimes, alas, not) recur with depressing regularity. Corruption is rampant, insolvency endemic. Ethnic propaganda flourishes unchecked. The liberal reformer Eleftherios Venizelos, the nearest thing to a hero this book has to offer, introduces minimum wages for women and children, mandates free primary education, makes civil service appointments conditional on entrance examinations. And, true to historical form, a lot of good it did him: he was forced out of office in 1933, nearly assassinated, driven into exile, condemned to death in absentia, and died in Paris.

Political parties, like the factions of Clisthenes’ day in the sixth century BC, remain basically personal, “coalescing around powerful personalities rather than platforms,” so that government and its offices are regarded as “prizes to be captured by rival cliques of politicians.” Cleon or Hyperbolus or Demetrius of Phaleron would feel quite at home in this atmosphere. The Balkan wars of 1912 were followed by the traumatic Greco-Turkish conflict culminating in the defeat of the Greeks at Smyrna in 1922. This finally collapsed the so-called “Great Idea,” the plan to recapture the lost Byzantine empire. The monarchy was out, in, out again (one king died inopportunely from the bite of a pet monkey). General Pangalos, a kind of poor man’s Nero, staged his brief opéra bouffe dictatorship in the 1920s, and the tough and efficient General Metaxas came to power just in time to clean up the army and say “No,” loudly, to an insulting Italian war ultimatum in 1940. Thus Greece was led into the conflict against the Axis, with all of the occupation, famine, and civil war that followed, a bitter interlude from which the country has arguably not recovered to this day.

It is during this charged period that the timeless quality of the Greek experience—and the Greek dilemma—most clearly emerges. The pattern is one that Thucydides recognized all too well. His memorable analysis (3.82-84) of the nature of civil war (stasis), as he found it on the island of Corcyra (Corfu) in 427 BC, was seldom far from my mind as I reread C.M. Woodhouse’s authoritative study The Struggle for Greece 1941-1949 (first published in 1976, but only recently made available in this country). “Society,” Thucydides wrote, “had become divided into two ideologically hostile camps, and each side viewed the other with suspicion.” As a result, “to fit in with the change of events, words, too, had to change their usual meanings.”

Fanatical opinions, he wrote, were at a premium, devious plotting became a mark of intelligence: familial ties were eclipsed by factional alliances. The ideals put forward sounded unexceptionable; but in fact public service became a cover for power-seeking, and the end always justified the means. Into just such a snakepit Woodhouse—an Oxford double-first in classics, a fluent Greek linguist, who was to become a historian, director of Chatham House and Tory minister—was dropped (literally) as a member of the sabotage team that in 1942 blew up the Gorgopotamos bridge (the most successful commando operation in mainland Greece), and stayed on, an incredibly youthful colonel, as commander of the Allied Military Mission to the guerrillas in German-occupied territory. Polybius, for one, would surely have approved his credentials.

Woodhouse not only survived his ordeal with distinction, but went on, eventually, to write the most thorough, scholarly, penetrating, and above all, impartial account of the resistance years and subsequent civil war. The publishers describe this as the “definitive history,” and for once that hyperbolic claim is well justified. Woodhouse goes to striking lengths to be fair to everyone, from royalists to communists: if almost everyone emerges looking singularly soiled, that is not his fault. Ideological posturings are given a heavy coat, in hindsight, of Thucydidean irony. The Greek Communist Party (KKE) was sold down the river by Stalin with callous indifference long before its cadres knew it, years before their heroic last stand (1949) in the Pindus mountains of northern Greece.

Woodhouse (like the Greeks themselves) divides their struggle into three episodes. First there was the period during the occupation, when the National Liberation Front was working to regain control of the country (and, more than incidentally, to get rid of the monarchy). Next came the abortive attempt by the communists to seek power in December 1944, at the time of the German evacuation, an attempt frustrated by the British. Finally, there was the long, escalating conflict of the civil war between 1946 and 1949. From the very beginning—though they did not learn, or admit, the awful truth until long after it was too late—KKE’s leaders, and a fortiori its rank and file, had been expendable, and as Woodhouse says, “without a trace of compunction, Stalin let them go to their doom.”

Yet it is hard to feel great sympathy for his victims, whose own execution squads, the dreaded “Units for the Protection of the People’s Struggle” (OPLA), were as ready to knock off supposedly deviationist comrades as mere bourgeois prisoners. They left a trail of mass executions behind them that, in 1945, shocked the fact-finding mission sent by the British Trades Union Congress out of its comradely British complacencies. Clogg reports11 that ELAS murdered some of the 8,000 civilians it took as hostages, and reasonably suspects a “backlash” in consequence. How far the right was provoked into counter-terrorism by such episodes, and how far the notorious right-wing Chi (X) brigades regarded their many indiscriminate killings as part of the game from the start (the latter is essentially Woodhouse’s view), remains uncertain. No one’s hands looked clean by the end. Some, like the noncommunist resistance leader General Zervas at least avoided organized wartime atrocities. Yet in 1947, as minister for public order, Zervas was to have so many communists arrested, and such a high proportion of them executed, that there were international protests.

By 1950 the government had lost an estimated 70,000 dead, the communists 38,000. But it was the communist terror that remained as a bloody ghost to haunt the Greek psyche: there is hardly a village in Greece, even today, where you are not likely to hear a litany of horror stories. “The rebels failed,” Woodhouse says, “because the mass of the people were against them, and when the Greek people had to choose, on balance, if without enthusiasm or euphoria, they deliberately chose the nation-state they knew rather than the communist paradise they were offered.” They had seen the dark side of that paradise, and knew its cost. “Nothing too much,” said the Delphic Oracle, an admonition only necessary in a country liable to recurrent bouts of excess. When the trauma was over (and what happened in Greece during those years was of immense historical significance, its consequences still with us today), the Greeks opted for constitutional rule, an avoidance of excess. Anyone who wonders why the Colonels’ stories of communist conspiracy found so ready an audience, or why Andreas Papandreou is so singularly ambivalent in his dealings with Moscow (or even with Eurocommunism) should bear this legacy in mind.

In diplomatic relations, the story is one of ineptitude rather than betrayal. If the KKE and ELAS had no leader such as Tito to unite them and canalize their energies (the story might well have ended differently if they had), then British policy in Greece suffered from a plethora of conflicting decision-making agencies, none of them fully coordinated. The Foreign Office worked through the Secret Intelligence Services (SIS), the Ministry of Economic Warfare used the special Operations Executive (SOE) as its agent, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff sent their directives through the Commander-in-Chief, Middle East, based in Cairo.

Woodhouse worked for SOE (which got a reputation for going its own way, regardless of Greek or British official policy), and clearly believes that it was largely responsible, by providing an alternative to KKE’s otherwise unique clandestine wartime network, for stopping the communists from forcing themselves on the Greek people. He may well be right. Certainly SOE’s field agents became alert to the political implications of ELAS much earlier than the diplomats, either British or American. As late as June 1944 Woodhouse was still briefing the American ambassador, Lincoln MacVeagh, on the communist domination of the National Liberation Front (EAM), which controlled ELAS.

MacVeagh is an intriguing, and often elusive, figure in this drama, about whom we now have, with the publication of a thick (and impeccably edited) volume of his ambassadorial reports, diary entries, and personal letters to Roosevelt, almost too much information to digest. He served in Athens from 1933 (about the time of the Venizelos assassination attempt) to 1940; and then, after tours in Iceland and South Africa, again until 1947, when he lost a battle of wills with the political appointee sent to run the Mission for Aid to Greece (AMAG)and was transferred to the Lisbon embassy.

From accounts by Woodhouse and by Bruce R. Kuniholm, as well as from his own reports, he comes across as a civilized, percipient diplomat of the old school, who nevertheless somehow failed to make quite the impact he should have done. To be fair, he did push for the regency that was established after December 1944 and he did, in theory at least, understand the nature of Greek communism early on. There was a streak of gentlemanly softness somewhere in MacVeagh. Roosevelt read his advice but by and large ignored it, his good contacts produced little action, his civilized manners were no match for the new ruthlessness of the cold war. Yet the State Department deprecated what it referred to as his “adventurism”!

He stayed on the sidelines—sometimes but not always by choice—during many of the serious crises. This was especially true of the attempted ELAS takeover in December 1944. Churchill’s cable to the British commander, General Scobie, telling him to treat Athens as a conquered city, and to shoot to kill if necessary, had been leaked to the American press. MacVeagh, already ruffled by the highhanded behavior of the British, who for several months had been virtually running the’ Greek government themselves, was caustic in private and pursued a studious official neutrality in public. He even refused British troops access to the well in his garden. Later, with the implementation of the Marshall Plan, it was America’s turn to play Big Brother in Athens; but by then MacVeagh was in Portugal.

As Bruce R. Kuniholm says in his book The Origins of the Cold War in the Near East, “first a battleground, then an occupied country, and then the scene of a bloody civil war, Greece—except for a brief moment in 1940-1941—was never able to draw upon the cohesive bonds formed by successful opposition to a common adversary.” It is the lesson of the Persian Wars and their aftermath all over again. The passions polarized by KKE and the monarchy were essentially negative. The chronic instability of Greek politics is a longterm product of Greek history, reaching back far beyond the Great Power rivalries and social schisms that Kuniholm isolates—schisms growing out of the localized loyalties of mountain brigands incapable of allegiance to a larger community or nation.

Such national unities as do exist have been forged largely by the Church, the armed services, and the kind of drumbeating ethnic and moral propaganda that these two institutions tend naturally to generate.12 In the 1940s, KKE tried for a different sort of unity, and failed catastrophically. Now Andreas Papandreou seems to be opting for the pseudo-neutralism of so-called thirdworld alignment, with the almost inevitable anti-American propaganda that this entails. Since it was the American food-relief program that largely staved off famine in 1944, since Andreas himself is (whether he likes it or not) heavily Americanized, and since, moreover, it has been Marshall Plan economics plus countless loyal Greek Americans that have borne a heavy share of the Greek financial burden in postwar hard times,13 this looks like a case of both beating one’s nurse and biting the hand that fed one. But PASOK’s political dilemma is all too clear—on the one hand, how to promote a radical; neutralist program without scaring the public too much; on the other, how to get votes with anti-American and anti-NATO rhetoric while not too seriously antagonizing the Western nations with which it will have to deal if it comes to power.

There seems, sometimes, an impassable gulf fixed between these harsh realities and the sunlit Greece of white-washed island chapels and bare bleached ruins, that summer paradise promoted in tourist guidebooks and the reminiscences of early classical dons, where Greeks, if they appear at all, do so as a piece of local color—the picturesque fisherman, the gnarled Cretan peasant, the bouzouki player. Looking, for instance, through a glossy book like The Greek World, one might be forgiven for supposing, on the basis of Eliot Porter’s photographs, that this was a world of dead stone, without a single living figure in the landscape. (By a nice, and I hope intentional, paradox, Peter Levi, in his prologue, identifies the main attraction of Greece for him as, precisely, people.) Too many visiting egotists, like Henry Miller in The Colossus of Maroussi, have simply used Greece as a backdrop on which to project their own outsize fantasies, and then have left again. Their passports free them to enjoy the beauty, ignore (or sneer at) the society; they get the best of both worlds. Yet of course both worlds are real, both form an integral part of the whole Greek (not foreign) experience. As Elytis so memorably demonstrated in The Axion Esti, politics, war, and landscape are indissolubly wedded, the beauty sustains the suffering, the suffering deepens and gives dark new meaning to the beauty.

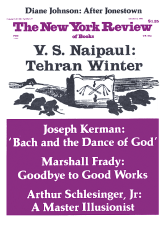

This Issue

October 8, 1981

-

1

Richard Clogg, A Short History of Modern Greece (Cambridge University Press, 1979), p. 211.

↩ -

2

Clogg, Short History of Modern Greece, p. 92.

↩ -

3

No serious, objective account of the junta’s collapse (or indeed of the whole period 1967-1974) has yet, to my knowledge, appeared. What I have read so far, by critics of the regime and its apologists alike, is rendered virtually worthless by the usual hysteria, special pleading, suppressio veri, exaggerated allegations, undocumented claims, and downright lies. If C.M. Woodhouse (see below) would consent to pluck this new apple of discord, we should all be greatly in his debt. No other student of the modern Greek political scene has half his qualifications—or one quarter of his impartiality.

↩ -

4

Taki Theodoracopulos, The Greek Upheaval (Caratzas Brothers, 1978), pp. 11-90. This maddening book, marred by unsupported gossip and disingenuous projunta whitewashing, nevertheless contains much valuable—and embarrassing—material. If ruthlessly re-edited and provided with a proper apparatus of documentation, it could be of real use to a future historian.

↩ -

5

C.M. Woodhouse, The Struggle for Greece 1941-1949 (Beekman Publishers, 1979), p. 141; cf. The Economist, January 31, 1976, p. 93. It is still widely believed in Greece (though Woodhouse does not mention this and therefore presumably regards it as a false rumor) that Aris Veloukhiotis did not commit suicide but was executed by order of Nikos Zakhariadis, secretary general of the Greek Communist Party (KKE). For a typical expression of this belief, see Theodor Kallifatides. Masters and Peasants (Doubleday, 1977), p. 140

↩ -

6

George Papandreou (d. 1968), prime minister of the wartime government-in-exile, and again in 1963 and 1964 as leader of the Center Union (EK). His resignation in 1965, after a clash with the young King Constantine, was followed by a succession of makeshift governments and, in April 1967, by the Colonels’ coup.

↩ -

7

Clogg, Short History of Modern Greece, p. 40.

↩ -

8

Clogg, Short History of Modern Greece, pp. 133-135; cf. Woodhouse, The Story of Modern Greece (Faber, London, 1968), pp. 229-237.

↩ -

9

See Nicolas Cheetham, Mediaeval Greece (Yale University Press, 1981), pp. 200ff.

↩ -

10

On Mistra itself we have the fine recent study by Sir Steven Runciman, Mistra, Byzantine Capital of the Peloponnese (Thames and Hudson, 1980).

↩ -

11

Clogg, Short History of Modern Greece, p. 156.

↩ -

12

While I was in Greece last summer the Church hit the Athens headlines twice: once directing the vials of its wrath against nude foreign bathing in the Peloponnese (which provoked some hilarious and irreverent cartoons), and once over the threatened prosecution of a priest for having the temerity to conduct the liturgy in demotiki, the vernacular, which to the Western observer might suggest that Orthodoxy is still in a pre-Wyclif phase.

↩ -

13

Kuniholm, Origins of the Cold War in the Near East, p. 99, n. 67; cf. Charles C. Moskos, Jr., Greek Americans: Struggle and Success (Prentice-Hall, 1980).

↩