The hundredth anniversary of Marx’s death is a good occasion to reflect on one of the central themes in his work: the problem of freedom. Strangely enough, this aspect of Marx’s thought is relatively neglected by Marxologists. And yet its relevance cannot be disputed. It is no exaggeration to say that Marx’s conception of freedom has proved to be extremely effective in “changing the world.” As an instrument of the most severe and powerful criticism of the classical liberal view of freedom, Marx’s concept exposed some important weaknesses of the early nineteenth-century version of liberalism. At the same time Marx’s concept produced dangerous consequences by radically questioning the central value of the liberal conception—individual freedom. This was so because, as I shall try to show, Marx replaced the idea of individual freedom safeguarded by law with an idea of the emancipation of humanity, conceived as collective salvation in history.

The term “freedom” has become notorious for the multiplicity of its meanings. It might be argued, however, that its basic and most generally used meaning coincides with the classical liberal view defining freedom “negatively”—as “independence of the arbitrary will of another.” According to this definition only man-made obstacles to individual effort can be described as a limitation of freedom. We can be free from constraint, from compulsion, but we cannot be free from natural necessity. Objective obstacles, independent of anybody’s will, put definite limits on our ability to do things; ability, however, should not be confused with freedom.

In contrast with this view, Marx saw freedom as man’s ability to exercise conscious rational control over his natural environment and over his own social forces. Thus he criticized liberalism from a position wholly outside the liberal tradition. Nevertheless, his criticism served, and still serves, as a mighty catalyst, making liberal theorists more alive to the social dimensions of freedom. How has this been possible?

First, Marx made liberals increasingly aware that in social life the distinction between objective impossibility and man-made obstacles is not clear enough. If poor people cannot afford to buy a great many things (although nobody forbids them to buy anything) this can be treated as a lack of capacity, and not as a limitation on their freedom; if, however, social relations and, by the same token, the distribution of national income are seen as man-made, the very fact that poor people are poor can be treated as the result of a man-made social order and, thus, as an enforced limitation of freedom. True, it would be straining matters somewhat to apply this interpretation to nineteenth-century capitalist societies, in which uncontrolled economic forces functioned, as Marx so often stressed, like natural forces. On the other hand, such an application grew less and less strained as the conscious regulation of the economy and the predictability of its social consequences increased. This explains, I think, the growing complication of the liberal conception of freedom and the increasing readiness of some left-wing liberals to learn from Marxism.

Secondly, Marx impressed liberal thinkers by invoking the idea of freedom as unfettered self-realization, the fullest possible development of the personality. This idea, which is firmly rooted, of course, in the liberal tradition, cannot be reduced to the narrow concept of negative freedom—freedom from arbitrarily imposed constraints; it implies also something positive, namely the possibility of the free development of one’s inherent capacities. It cannot be denied that in this particular sense the ideal of freedom demands not only independence from the arbitrary will of another but also the removal of those social and economic conditions which hamper the fullest possible development of the individual. The ideal of freedom, that is, demands not only minimizing external constraints, but also creating optimal conditions for everyone’s fullest personal development.

We can turn now to the exposition of Marx’s views and, in particular, his criticism of liberalism, which highlights the peculiarities of his own conception.

Marx was indeed an uncompromising unmasker of what he called bourgeois freedom, by which he meant primarily economic freedom, freedom as nonintervention by the state in the sphere of civil society. The latter he defined, following Hegel, as a sphere of conflicting egoistic interests competing or struggling with one another within the framework of private law. Freedom so conceived he labeled “the liberty of capital freely to oppress the worker.” He attacked it with fury, treating liberals as shameless apologists of bourgeois exploitation. He refused to agree that the pressure to sell one’s labor, unlike direct compulsion, was compatible with freedom, and repeatedly asked how a contract between a proletarian and a capitalist could be called free if the former acted under threat of death by starvation.

This was the aspect of Marx’s view of freedom that most deeply impressed his contemporaries. It was central to his entire theory of capitalist development: to his conception of primitive accumulation as necessarily entailing the wholesale expropriation of small producers, to his view of the nature of bourgeois exploitation and of the proletarian condition, which he ironically described as “freedom from the means of production,” and, finally, to his analysis of the historical role and alienating function of the social division of labor.

Advertisement

Much less well known, although equally revealing, is Marx’s attitude toward the legal rights of man as safeguards of individual freedom. It is expressed most clearly in his early article “On the Jewish Question” (1844), where he makes a sharp distinction between the rights of man and the rights of a citizen. The first are the rights of private men seeking a legal guarantee of their negative freedom; the second are rights of political participation in the public sphere of human existence which give people their share in political decision making. Marx condemned the first category outright. “The right of man to liberty,” he argued, “is based not on the association of man with man, but on the separation of man from man.” It guarantees the freedom of man as an isolated, self-sufficient monad; the practical application of such freedom is man’s right to private property, and its essence is the law of egoism which “makes every man see in other men not the realization of his own freedom, but the barrier to it.”

Marx made this severe condemnation of the very concept of the rights of man, the cornerstone of the liberal world view, because, as Allen E. Buchanan has aptly put it, he “thought of rights exclusively as boundary markers which separate competing egoists.” To put it differently, the concept of a person as essentially a bearer of rights was in his eyes “a radically defective concept that could only arise in a radically defective form of human society.”1 Man as the subject of rights and the egoistic economic subject of capitalist civil society were for him two sides of the same coin.

Marx’s attitude toward the second group of rights—the rights of the citizen, rights of political participation—was much more complex. Like many other German thinkers, including the young Hegel, he was under the spell of the ancient polis democracy; he deplored the privatization of life in modern times and sharply contrasted the public freedom of the ancient Greek citizen with the private, egoistic freedom of the modern bourgeois. In his early Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law (1843) he even expresses a hope that universal suffrage, i.e., making universal the rights of political participation, will abolish the dualism of state and civil society by liquidating the autonomy of the private sector and making civil existence inessential by contrast to political existence. This would amount, he thought, to a restoration of the ancient heroic virtues, as contrasted with bourgeois egoism.

We can see from this how inimical Marx was to liberal values even in the precommunist stage of his ideological development. He saw no positive value in privacy; his ideal of the total subordination of the private sphere to the public sphere, of extending the scope of political decisions to all spheres of life and thus abolishing the autonomous existence of economy, deserves to be classified as a kind of democratic totalitarianism.

The wholly different liberal approach to these problems was shown by Benjamin Constant in his famous lecture “Of modern freedom compared with the freedom of the ancients” (1819). He defines ancient (democratic) liberty as participation in political power, by which the citizen takes an active part in collective sovereignty—in other words, as political democracy extending its rule over all spheres of human life. In contrast to this, he argues, the essence of modern (liberal) freedom is precisely the existence of a private sphere with which no state, even the most democratic, has the right to interfere.

Thus the ancient freedom, unlimited popular sovereignty, is fundamentally incompatible with modern freedom—the freedom of the private individual, as the Jacobin phase of the French Revolution all too clearly showed. Therefore political freedom can be accepted by liberals only if the rights of man are recognized as something prepolitical and inalienable, limiting the scope of political power, regardless of its source. In this case, if the autonomy of the private sphere is sufficiently protected, political democracy may function as a guarantee of modern liberty; if not, an undemocratic but limited government is greatly preferable to the omnipotence of a democratic state.

Marx’s view was diametrically opposite—he accepted political freedom only on condition that it was not combined with the rights of man and not used as their safeguard. Commenting upon the French “Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen,” he wrote:

Advertisement

It is puzzling enough that a people which is just beginning to liberate itself, to tear down all the barriers between its various sections, and to establish a political community, that such a people solemnly proclaims [“Declaration” of 1791] the rights of egoistic man separated from his fellow men and from the community, and that indeed it repeats this proclamation at a moment when only the most heroic devotion can save the nation, and is therefore imperatively called for, at a moment when the sacrifice of all the interests of civil society must be the order of the day, and egoism must be punished as a crime [“Declaration of the Rights of Man,” etc., of 1793]. This fact becomes still more puzzling when we see that the political emancipators go so far as to reduce citizenship, and the political community, to a mere means for maintaining these so-called rights of man, that therefore the citoyen is declared to be the servant of egoistic homme, that the sphere in which man acts as a communal being is degraded to a level below the sphere in which he acts as a partial being, and that, finally, it is not man as citoyen, but man as bourgeois who is considered to be the essential and true man.

Soon after writing these words in “On the Jewish Question,” Marx ceased to be puzzled by the fate of the rights of the citizen in capitalist societies. Having become a full-fledged communist and the founder of historical materialism, he came to the conclusion that under capitalism politics must serve the egoistic interests of man as “bourgeois” and that to think otherwise amounted to cherishing petty-bourgeois democratic illusions. As long as capitalism exists, civil society is stronger than the state and the political sphere is merely a superstructure whose autonomy in relation to the economic sphere can only be relative.

With this conclusion Marx’s attitude to political democracy underwent a considerable change. Political freedom ceased to be for him an end in itself, becoming instead a means of struggle; a means whose value was relative, depending on many different factors. He no longer thought of it as being able to resurrect the ancient public virtues and curb bourgeois egoism; on the contrary, it followed from his analysis of the capitalist system that it was always more formal than real, serving the interests of the propertied classes and, therefore, deserving to be unmasked rather than glorified.

The Russian populists, who were among the most ardent readers of Capital, concluded from it that political freedom is merely a deception, an instrument of bourgeois class rule, and hence that it is not worthwhile to fight for its introduction. Similar views were developed in the West by anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists, who also tried to support their nihilist attitude toward political democracy by invoking the authority of Marx. It is appropriate therefore to stress that Marx himself was very far from such ideas. He did not deny the relative value of parliamentarianism, he deeply hated “patriarchal feudal absolutism” and repeatedly emphasized that capitalism with political democracy is, as a rule, much better, much more progressive than capitalism combined with a different kind of political superstructure.

So Marx should not be accused of a nihilist attitude toward political freedom. On the other hand he cannot be seen as supporting political freedom for its own sake, as a principle. Under capitalism, he thought, political freedom can further capitalist progress, sometimes it can even serve as a means of proletarian class struggle, but as a part of the capitalist superstructure it can never be a form of true freedom.

In making a general assessment of Marx’s views of freedom on the legal and political plane, we must always remember his sharp distinction between the rights of man and the rights of the citizen. If his attitude toward the latter was ambiguous, his attitude toward the former was unambiguously negative and utterly contemptuous. In contrast to this, the classical liberal tradition emphasized just those nonpolitical human rights; the modern liberal-democratic tradition ceased to make a sharp distinction between nonpolitical rights and the rights of political participation, emphasizing rather their practical inseparability. We may conclude therefore that Marx’s views on political and civil liberty are incompatible not only with classical liberalism (to which they were diametrically opposed) but with the new democratic liberalism as well.

We can now proceed to Marx’s positive conception of freedom. It is impossible in a short article to analyze all the complexities of this conception, to explain, for instance, in what sense Marx saw the historical process as necessary and meaningful. But in order for us to understand Marx’s idea of freedom, it is necessary to introduce here a somewhat difficult concept of self-enriching alienation—a concept that underlies the entire Marxian philosophy of history.

The term “alienation”—originally a theological term, taken up and developed by Hegel, Feuerbach, and other German thinkers—means, first, the process by which something goes out of itself, becoming something different from and alien to its essence, and, second, giving something away, relinquishing something of one’s own being, undergoing an amputation, as it were. In this sense the Incarnation was the alienation of God, who had to relinquish his divine attributes to assume a nondivine corporeal form. In a similar sense Hegel wrote about the alienation of the Spirit (Geist) which had to become exterior to itself to constitute the material world. Self-enriching alienation is the concept of a dialectical movement through alienation to self-enrichment. Thus the entire period of man’s separation from God after the Fall could be interpreted as a journey from paradise lost to paradise not only regained but also enriched—enriched by the knowledge of what is good and what is bad, by freedom and consciousness. Similarly, in Hegelian philosophy the Absolute Spirit alienates itself in time, in order, after achieving the climax of alienation, to absorb into itself its alienated content and thereby to enrich itself, raise itself to the level of self-consciousness.

Marx is known to have been deeply impressed by Feuerbach’s reversal of the Hegelian (and Christian) view of alienation: by the claim that it was not the Absolute Spirit that had alienated itself in the world and in man, but, on the contrary, that it was man who had alienated his generic essence by externalizing it in the image of God. This so-called religious alienation was seen as self-enriching: true, by creating God man had impoverished himself, as it were, and, moreover, had become dominated by his own creation; however, to overcome this alienation would entail the absorption of the divine attributes by man, thus making man a truly divine being.

Marx followed Feuerbach in relating his theory of alienation to the generic essence of man; but his own theme was the socioeconomic alienation that occurred through the social division of labor in conditions of private ownership of the means of production—a process that entered its culminating phase with the development of modern capitalism. He saw the capitalist market as a force created by man but alien to man, having its own quasi-natural laws of development, opposing man and dominating him, thwarting man’s plans instead of being subjected to plans consciously settled by producers. Thus man became enslaved by his own products, by things; even interhuman relations became “reified,” i.e., took on the appearance of the objective relations between commodities in process of exchange, completely independent of man’s will. This “commodity fetishism,” or reification, was in Marx’s view the worst, and a peculiarly capitalist, form of alienation.

By contrast, Marx described communism as “the positive transcendence of private property“; as “the real appropriation of the human essence by and for man”; as “the complete return of man to himself as a social (i.e., human) being—a return accomplished consciously and embracing the entire wealth of previous development”; as “the riddle of history solved” and knowing itself to be this solution.

This quotation from the young Marx is remarkably revealing. It perfectly fits the pattern of self-enriching alienation since man’s return to himself is seen as self-enrichment, as a return on a higher level. It shows communism as the preordained goal of history, thus exposing the teleological structure of the Marxian philosophy of history. Finally, it describes communism as necessary for the sake not of equality but of the full self-actualization of the human essence, that is, for the sake of freedom, as Marx understood it. And it should be added that, despite many qualifications, despite the appearance of a naturalist scientism, the same pattern of thought is to be found in the works of the mature Marx, the author of Capital.

The self-actualization of the human essence in history, i.e., the realization of freedom, was, in Marx’s view, a process of liberating man from the domination of things—both in the form of physical necessity and in the form of reified social relations. In order to liberate himself, to develop all capacities inherent in his generic essence, man must be able to exercise conscious rational control over his natural environment and over his own social forces. Hence freedom in this conception has two aspects. In the relation “man versus nature” it consists in maximizing the power of the human species, achieved through the development of productive forces; because of this Marx indignantly rejects romantic protests against alienating industrialism in the name of preindustrial harmony; he does not even hesitate to praise Ricardo for voicing the principle of “production for production’s sake,” since that principle means for him “the development of the wealth of human nature as an end in itself.” In the relation “individual-society,” freedom means for Marx a conscious shaping by men of the social conditions of their existence and so eliminating the impersonal power of alienated, reified social forces; in this context he describes the future free society as “the association of individuals [assuming the advanced stage of modern productive forces, of course] which puts the conditions of the free development and movement of individuals under their control.”

In both cases freedom is conceived as the ability to control one’s fate, as positive freedom; in both cases freedom is opposed not to arbitrary coercion but to the uncontrolled objectivity of impersonal forces—both natural forces and the forces of historically produced “second nature,” that is, the quasi-natural functioning of alienated social forces. Finally, freedom thus conceived is inseparable from rationality, from rational predictability, and opposed to the irrationality of chance. Capitalism is condemned as not being rational enough and the final victory of freedom is seen as the replacement of market mechanisms with “production by freely associated men, consciously regulated by them in accordance with a settled plan.”

Such a notion of freedom was deeply rooted in the classical German idealist tradition, which saw man’s dependence on things (subject on object, consciousness on elemental and uncontrolled processes) as deeply humiliating and unworthy of a rational creature. The antiliberal implications of such a hierarchy of values are visible most clearly not in the mature Hegel, who accepted the existence of “civil society” as an autonomous sphere of particular, private interests (and was severely criticized by the young Marx for it), but in the young Hegel and especially in Fichte. Freedom for Fichte had nothing in common with the free pursuit of individual desires, inevitably resulting, as he thought, in the irrational reign of accident. He was interested not in the liberty of empirical men but in the positive freedom (i.e., maximum power) of the transcendental ego, the noumenal subject. In his utopia of “the closed state” (considered to be socialist by some Marxists of the Second International) the rational, totalitarian state was treated as an instrument of freedom—an instrument of the collective rational ego, which controls and determines itself, and in this way liberates itself from the power of blind necessity governing the world of things.

According to Marx, the two aspects of freedom represented two successive stages in the history of self-enriching alienation: maximizing the productive powers of the species at the cost of alienation (capitalism) and the disalienation of these powers by rational planning (socialism). Following Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit he saw the capitalist epoch as the most alienated and most progressive so far, since in the past progress had to be paid for by alienation. With respect to the development of man’s productive powers, capitalism was, of course, a triumph of freedom; but with respect to man’s control over his own social relations, it represented at the same time the greatest denial of freedom, the most complete domination by alienated and reified forces.

On this view, we read in The German Ideology (1845-1846), it is merely a bourgeois illusion that capitalism has liberated the individual; in fact what the bourgeoisie calls personal freedom boils down to leaving the fate of individuals to chance, which is the other aspect of the blind necessity that governs social relations as a whole. “Thus, in imagination, individuals seem freer under the dominance of the bourgeoisie than before, because their conditions of life seem accidental; in reality, of course, they are less free, because they are to a greater extent governed by material forces.”

Another and even more important reason for seeing capitalism as a system destructive of freedom was the capitalist division of labor, separating the productive powers of the species from individual human beings. From this angle Marx’s Capital turns out to be a contribution to the philosophical debate on freedom. The development of the division of labor—at first inside the factory and subsequently within the frame of society as a whole—is there interpreted as a process of the “socialization of labor,” which leads to the maximum development of human productive forces at the cost of their alienation: in other words, a process that attains an economically integrated society at the cost of the utter disintegration and fragmentation of the individual. The products of “socialized” labor, i.e., divided and specialized labor, are the products of all and at the same time of nobody—things wholly impersonal, living an independent life and subjugating their producers. The collective laborer develops at the expense of the individual laborer: “in order to make the collective laborer, and through him capital, rich in social productive power, each laborer must be made poor in individual productive powers.”

Similar accusations were leveled against capitalism by the conservative-romantic critics of modern civilization and by representatives of “economic romanticism,” such as Sismondi. Marx wholly agreed with their gloomy descriptions of the facts but rejected their conclusions. He repeatedly emphasized that capitalist development, with all its cruelties, was an “iron necessity,” an inevitable phase in universal progress, and ridiculed its moral condemnation as based on unhistorical judgment, sentimentalism, and utopianism. Regardless of the correctness of this view, his attitude toward what he believed to be the necessary price of capitalist progress revealed a peculiar trait of his thinking: his readiness to sacrifice the present generation, or several generations, for the sake of the future. Using the Nietzschean distinction one may say that he passionately loved what was far off (Fernstenliebe) and exhibited a conspicuous lack of love for his neighbor (Nächstenliebe).

This feature of his thought and of his moral world view was inherited by most of his disciples in different countries. They were indeed rarely sentimental. The nineteenth-century Russian Marxists ridiculed the Russian populists, who wanted to defend the Russian peasants against the cruelties of primitive accumulation, as described in Capital. They saw the expropriation of the small producers as a prerequisite of capitalist industrialization, as an objective necessity, and the very idea of defending the victims of progress was for them the quintessence of petty-bourgeois reactionary utopianism. What was done to the peasants and to other groups after the Russian disciples of Marx had seized power is only too well known. “Historical inevitability” and “the necessary price of progress” became an excuse for anything.

In the communist future, of course, the contradiction between the interests of the species and the interests of the individual was expected to disappear, to “wither away” like the state, law, and other forms of alienation. It seems amazing today that Marx really did believe in the miraculous power of nationalizing the means of production. This rather simple device seemed to him to do away with the separation of man’s capacities as a species from his capacities as an individual, and to create a many-sided, universal man, a “species man,” who would contain in himself “the entire wealth of previous development.” In The German Ideology he wrote:

The appropriation of these forces [of production] is itself nothing more than the development of the individual capacities corresponding to the material instruments of production. The appropriation of a totality of instruments of production is, for this very reason, the development of a totality of capacities in the individuals themselves.

“Scientific socialism,” that is, the socialization of the means of production, thereby liberating man from the alienating power of the economy, was defined by Engels as “the ascent of man from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom.” It is proper to stress that Marx held a somewhat different, more sophisticated view. For him the higher possible development of productive forces and their subjection to conscious, planned control was only an indispensable condition of authentic freedom. In the third volume of Capital he abandoned his earlier vision of alienated specialized labor that would be replaced by free, diversified activity, and he put forward instead a distinction between true freedom and “freedom within the realm of necessity.” “In fact,” he wrote, “the realm of freedom actually begins only where labor, which is determined by necessity and mundane considerations ceases; thus in the very nature of things it lies beyond the sphere of actual material production.” In the sphere of production, freedom

can only consist in socialized man, the associated producers, rationally regulating their interchange with Nature, bringing it under their common control, instead of being ruled by it as by the blind forces of Nature; and achieving this with the least expenditure of energy and under conditions most favorable to, and worthy of, their human nature. But it nonetheless still remains a realm of necessity. Beyond it begins that development of human energy which is an end in itself, the true realm of freedom, which, however, can blossom forth only with this realm of necessity as its basis. The shortening of the working-day is its basic prerequisite.

Thus the attainment of freedom in the realm of necessity will enable men to acquire the material means and free time needed to satisfy comprehensive, “abundant,” truly human needs, creating thereby the conditions for true freedom—the unhampered realization of all faculties of man’s species nature. In other words, the victory of communism will usher in the appearance of the new, regenerate, superior man. As we see, this ideal has nothing in common with the egalitarian leveling down that is characteristic, to quote Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, of primitive communism, which postulates “the regression to the unnatural simplicity of the poor and crude man who has few needs and who has not only failed to go beyond private property, but has not yet even reached it.” Marx’s vision of the ultimate ideal could be described rather as a kind of superman—a superman, not in the Nietzschean sense of a new species transcending humanity, but, on the contrary, a superman by virtue of his full realization of man’s species capacities, a “true” man as opposed to “real men,” i.e., the underdeveloped and degraded human beings of the presocialist epochs of history.

This is, I think, an impressive utopian vision. Its purely utopian character is manifest in Marx’s belief that after the means of production have been socialized, the new, superior race of men will appear of its own accord as the result of the creative drive for self-development inherent, as he thought, in human nature. He did not foresee the possibility that, even in a socialist welfare state, men might still be dominated by a bourgeois scale of values, that their needs and aims might remain just as mean and egoistic, just as “inhuman” (by his standards) as under capitalism. And it never occurred to him that actual human beings might not want to be “liberated” from their egoism, particularism, and other features incompatible with what he saw as man’s generic essence. This is why it is not enough to say that his ideal of the emancipation of mankind was different from the liberal ideal of individual freedom; we must realize that the two ideals are incompatible, mutually exclusive.

This was perfectly understood by Georg Lukács—a thinker who, I believe, penetrated most deeply the Promethean and romantic spirit of the Marxian utopia. The “freedom” of men now alive, he reasoned, is “the freedom of the individual isolated by the fact of property which both reifies and is itself reified.” It can “only be corrupt and corrupting” and, therefore, the conscious commitment to true freedom “must entail renunciation of individual freedom. It implies the conscious subordination of the self to that collective will that is destined to bring real freedom into being…. This conscious collective will is the Communist Party.”2

To be fair, we should add here that Marx himself did not draw such a conclusion. He thought it would suffice to remove such obstacles as the humiliating dependence on things and the alienation of social forces, and did not foresee that even then the human essence might be reluctant to reveal its richness. On the other hand, he cannot and should not be exonerated from blame for the deeds of those of his disciples who decided that in such a case it would be necessary to teach men their true “generic essence” through forcible indoctrination (“socialist education”) and other coercive means, including physical elimination of the incorrigibly unregenerate. His utopian vision of earthly salvation was combined with lack of concern, if not outright contempt, for the real human beings in whom the noumenal essence of man was manifested in a distorted way. Experience has shown that such a combination is bound to produce totalitarian consequences.

At the beginning of this essay I acknowledged that Marxism has served as catalyst in the progressive evolution of liberal thought. Now, however, I would like to stress that, in spite of this, the gap between genuine, undiluted Marxism and left-wing liberalism or liberal socialism cannot be bridged, except, of course, at the cost of surrendering liberal values. It is a grave mistake to present Marx as a kind of ethical individualist in the liberal sense, since he never shared Kant’s view that each person must be treated as an “end in itself,” and never as a means. He never accepted the principle that “society’s obligation runs first to its living citizens.”3 On the contrary, he was always ready to sacrifice the present generation for the sake of the future.

This was so because he was concerned with the “liberation” of the superior capacities inherent, as he thought, in the species nature of man; he was not concerned with individual freedom, seeing it, quite correctly from his point of view, as sanctifying different kinds of particularism and incompatible with his scheme for subjecting socioeconomic development to planned, conscious control. And, most surely, he was as far removed as possible from liberal political doctrine. He thought that the true legitimation of any social and political order is provided by the inner logic of history, which he claimed to know, and not by the will of the electorate. No wonder therefore that his true followers derived from his views the certainty that history itself gave them a mandate to exercise power in the name of its final goal, that its verdict is irreversible, and that in no circumstances therefore can they give up this power.

Kautsky, Plekhanov, and other Marxists of the Second International made absolute the quasi-scientific side of Marxism: its economic determinism and the theory of development leading, allegedly, to the inevitable breakdown of capitalism (Zusammenbruchstheorie). This side of Marxism, bound up with an optimistic belief in automatic progress, is now almost completely forgotten; we are witnessing instead an amazing revival of the voluntarist, activist, and utopian elements of Marxism. The Sorelian term “myth” is an even better description of what has happened: the Marxian legacy has become the most fertile ground for breeding different kinds of myths, some of them intellectually inspring but most of them generating a millenarian faith in earthly salvation and, therefore, dangerous and destructive of the relative but more tangible achievements of human progress.

On the other hand it is undeniable that Marxism gave birth to a fruitful and academically respectable methodological approach to the social sciences; that it provided, and continues to provide, some valuable insights for the criticism of modern civilization and culture. We should ask therefore: is it possible to preserve Marxism as a part of our cultural heritage, to assimilate it, and, at the same time, to be immune to its myth-creating political influence?

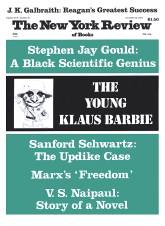

This Issue

November 24, 1983

-

1

Allen E. Buchanan, Marx and Justice: The Radical Critique of Liberalism (Rowman and Littlefield, 1982), pp. 163, 51.

↩ -

2

Georg Lukács, History and Class Consciousness (MIT Press, 1971), p. 315.

↩ -

3

Ronald Dworkin, “Why Liberals Should Believe in Equality” (The New York Review, February 3, 1983), p. 34.

↩