There are times when one wishes that the great art historians and theorists of the past who wrote biographies of their contemporaries had been more like the art historians of today…. Put like that the wish appalls by its condescension and Philistinism. Can one really imagine the intelligence and imagination of Vasari or Bellori confined within the pages of an “Outstanding Dissertation in the Fine Arts” or of a contribution to the Art Bulletin or Burlington Magazine? Nonetheless the fact remains that Marcantonio Michiel (who in the first half of the sixteenth century was planning to write a history of Italian art) could have asked Giorgione himself, or at least one of his friends, whether his (Michiel’s) description of the Tempesta as “the small landscape…with the storm, the gypsy and soldier” was an adequate one, or whether this beautiful and enigmatic picture in the Accademia in Venice did not really represent an abstruse legend involving Hermes Trismegistus (or whatever fanciful theory currently holds the field). The answer might perhaps have spared us several dozen articles in the learned journals of today.

Bellori, who was surely among those who would sometimes accompany Poussin on his early morning walks on the Pincio, during which he would “engage in curious and learned conversations with his friends,” could easily have inquired of the master whether in some of his late mythologies (such as The Birth of Bacchus, now in the Fogg Art Museum) he was thinking of the philosophy of Campanella (as has recently been claimed) or merely of the poetry of Ovid (as Bellori himself tells us). If any such question was put (and what Ph.D. student of today would not have put it?), the answer was not committed to paper.

The absence of both any (recorded) question and any (recorded) answer could have its own significance. As far as I know only one attempt has been made to account for the apparent lack of concern shown by the great writers of the past to some of the problems that most tantalize us today. In a challenging article published a few years ago1 Leo Steinberg suggested that Vasari’s famous (or notorious) description of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel was deliberately intended to be misleading in order to protect the artist from any danger to him that might have arisen from the possibly heretical implications of his fresco. Vasari gives a brief and somewhat conventional account of the principal figures and sums up Michelangelo’s aims as

none other than to paint the most perfect and best proportioned composition of the human body in the most varied attitudes—and not just this, but at the same time, the effects of the torments and gratifications of the soul: satisfying himself with this part of the art, in which he has been superior to all other artists, and has demonstrated the way to the grand manner and the treatment of the nude and his knowledge of the difficulties of design; and he has facilitated the approach to the principal aim of art—the human body.

Whether or not we accept, wholly or in part, Steinberg’s ingenious argument that this account of the fresco is meant to distract attention from its deeper and by then perhaps subversive meaning (and such tactics would bring to mind Zola’s description of Manet’s potentially indecent Déjeuner sur l’herbe as a sort of abstract pattern of shapes and colors), it is at least tempting to speculate that the art historians of the past could, on occasion, wrestle with issues that are bound to interest us—and then deliberately conceal the fact: for much surviving evidence makes it very difficult to believe that they were indifferent to such issues or that (as obviously sometimes happened) they felt it unnecessary to discuss what would have been perfectly obvious to their own contemporaries.

From the early nineteenth century onward those interviews whose earlier absence so teases us (“But what does Neoplatonism actually mean to you, Signor Vecellio?”) begin to make an appearance in the art-historical literature—but by now it was too late: for with the coming of Romanticism the best artists often claimed to be doing something for which by definition no verbal explanation could be given. How often we hear them complaining that meanings have been read into their works that had never occurred to them. Not always complaining, of course: for many of them were understandably delighted with being given the credit for having plumbed greater depths than they had actually been aware of and welcomed the most preposterous “explanations” of their work.

But before the French Revolution (to take an approximate but convenient date) it had been accepted for some centuries that there was a clear relationship between painting and literature (or the literary approach) and that in that relationship painting was, so to speak, the junior partner. It is not therefore wholly absurd to imagine Antoine Watteau giving perfectly coherent answers to some of the questions we would like to have been able to put to him after visiting the beautiful exhibition of his works that closed in Washington in September and—in even more splendid versions—has moved on to Paris (until February) and Berlin.

Advertisement

Contrary to what is sometimes claimed, the biographies of Watteau are in many respects remarkably full and informative—more so than those of almost any other artist in eighteenth-century France, and they help to make up for the fact that not a single authentic letter from him has certainly survived. He evidently made a very striking impact on his friends and contemporaries, and at least seven of them wrote about him—though some of them very briefly indeed. Despite their differences in approach a consistent pattern emerges of a moody, difficult, restless painter whose attitude of pessimistic fatalism is summed up in the chilling remark he once made to a worried friend who was trying to encourages him: “le pis-aller, n’est-ce pas l’hôpital? On n’y refuse personne“2—and this was apparently said before the onset of the tuberculosis that was to kill him in 1721 at the age of thirty-seven.

The Comte de Caylus, the scholar and theorist who reports this episode, was—though much derided by Diderot and others as a bully and a pedant—the most interesting, cultivated, and (in some ways) sympathetic of Watteau’s biographers. For in his account of the artist, which was given as a lecture to the students of the Academy, he found himself having to reconcile his deep personal affection for him, which had evidently been reciprocated, with his own views on painting, which were utterly at variance with everything he believed to be characteristic of the dangerously seductive work of his dead friend. For these reasons Caylus is, in some ways, just the kind of articulate and critical biographer whose evidence (as I suggest) ought to be most welcome to us: much modern writing about Watteau is devoted to disputing what Caylus has to tell us about him.

“When we used to draw together from the model,” Caylus recalled nostalgically,

we experienced, he and I…, the pure joy of youth, combined with the free play given to our imaginations…. I can say that Watteau who everywhere else was so somber, so atrabilious, so shy and so caustic was, on these occasions, simply the Watteau of his own paintings: that is to say, pleasant, gentle and perhaps a little rustic or unsophisticated, as indeed we would conceive of him from looking at his pictures.

For Caylus, Watteau was an artist whose achievement failed to match his ambition. (This may, of course, have been Caylus’s ambition for him.) Despite his admirable devotion to the practice of drawing from life, he was never able to master the nude; he could not cope with history and allegorical painting, and he was infinitely mannered. Above all, according to Caylus, Watteau’s refusal to make preliminary studies for his paintings, and his habit of selecting for them figures picked almost at random from his stock of drawings and only then making a composition, meant that these compositions “have no subject.” Because Watteau did not depict the “passions,” his pictures are void of true “action”—and in this context the word “passions” surely means the overt expression of states of mind and feeling, while “action” implies legible narrative.

Thus Caylus, the witness, made use of his account of Watteau’s working methods (an account which research has shown to be substantially, though not invariably, accurate) in order to interpret the essence of his finished pictures, and his interpretation can be justified insofar as it provides a perfectly reasonable explanation of what we actually see on most of the canvases: elegantly dressed men and women engaged in some sort of relationship to one another, but a relationship so imprecise that commentators have often been prepared to consider the imprecision itself as constituting the poetry, rather than as detracting from it as did Caylus.

The aim of Donald Posner’s new book (and also of some of the entries in the exhibition catalog) is—partly at least—to challenge both these approaches and to argue that “the meanings of Watteau’s fêtes galantes are far more explicit and more accessible than often thought.” Whereas too many writers have been less concerned to understand meanings than to concoct a suitably musical language with which to match the music of the pictures (the analogy is inescapable), Posner’s admiration is characterized by steady concentration and curiosity, and he makes careful use of the titles given to them in the engravings made soon after Watteau’s death, for these may well reflect the artist’s intentions.

Advertisement

Posner’s insights are often valuable and convincing, though they are sometimes expressed in unfortunate prose: “In La Lecon d’amour [Stockholm]…the scene centers on the efforts the company makes to establish relationships.” This suggests a session of group therapy, but Posner more usually discusses the pictures themselves with tact and sensitivity. Indeed, the fact that his thoughtful book constitutes the most stimulating investigation into the art of Watteau now available makes it all the more regrettable that so many of the plates are of such indifferent quality. The hefty and very informative Washington catalog is well illustrated, but obviously the selection of works reproduced reflects those actually exhibited, which means that some masterpieces have had to be excluded.

Posner’s interpretations (and those by some of his predecessors) demonstrate that for all Watteau’s mastery of “patterns of behavior and emotional content in order to reveal psychological under-currents, the tensions, frustrations and longings in human relationships and social intercourse,” the pictures can only very rarely in themselves be made to reveal their secrets (if they have any), and it is often necessary to call upon extraneous evidence—with varying degrees of success. Like the artists of the seventeenth-century Low Countries to whom his art owed so much, Watteau probably made use of puns and proverbs in a manner that would have been obvious to his contemporaries.

Posner is clearly right to claim that La Marmotte (Hermitage) and its pendant La Fileuse (known through an engraving) provide examples of sexual innuendo based on such assumptions. But the theory that because it was apparently difficult to tune a lute we should always look upon the musicians holding these instruments in his pictures as “bumbling lovers” is by no means convincing, and Posner’s interpretation of Les Charmes de la vie (Wallace Collection) along these lines strikes me as a dangerous example of the extent to which ambiguous visual evidence can be stretched in order to fit a preconceived pattern.

I am by no means sure, moreover, that when in the Rendez-vous de chasse (Wallace Collection) Watteau copied the figure of the lady dismounting from a detail of Callot’s print of The Fair at Impruneta he “knew, of course, that his sophisticated audience would recognize the source of the group.” It is always chastening to discover how rarely even the most “sophisticated” art lovers seem to have recognized quotations of this kind before the installation of university photographic libraries. Nonetheless Posner’s exploration of the world of Watteau’s admirers, friends, and patrons (supplemented by further information in the catalog) is of notable interest and value.

We learn that the artist was mainly (but not, of course, exclusively) supported by men who were not very prominent in the cultural life of their time, “people of average abilities and ambitions,” who were often more interested in speculation than in building up representative or coherent collections. Posner, in fact, shrewdly suggests that many of Watteau’s clients purchased his pictures on the recommendation of his friends and were not likely to be familiar with developments in the contemporary art world. There is a certain irony in the thought that it was such men who were promoting one of the most remarkable of all pictorial revolutions. It does make one wonder yet again how far they would be likely to appreciate some of the more ingenious intentions attributed by Posner and others to the artist.

Our perplexities when faced with the problems of trying to unravel Watteau’s narratives (if such they are) and his relationship to his public become even more frustrating when we consider an aspect of his art which is obviously more fundamental and which, we feel, ought to be less baffling: its mood. To his friends there appeared to be a clear conflict between the gaiety of his themes and the melancholy of his temperament. But more than a hundred years after his death, when the Revolution had swept away the world that he had celebrated, this conflict was resolved to many people’s satisfaction by the suggestion that his pictures were themselves melancholy in feeling—art lovers have always been fascinated by the proposition that “le style c’est l’homme même,” and we have seen that Caylus tried to resolve the discrepancy between art and life by claiming that, when in a good mood, Watteau could be as “agréable” as his pictures. To Posner, however, the supposed “melancholy” of Watteau’s art is a historical misconception, and it is partly for this reason that he rejects what has been one of the most enlivening contributions made to our interpretation of Watteau’s paintings in recent years.

Caylus specifically excluded the picture that he called L’Embarquement de Cythère (Louvre) from his complaints about the lack of any real subject in Watteau’s compositions, but in fact hardly had it been presented to the Academy in 1717 under the ambiguous title Le Pèlerinage à l’Isle de Cithère (“Pilgrimage to” or “on the Island of Cythera”) before these words were crossed out in the record to be replaced by the more noncommittal feste galante. However, when it was inventoried some sixty years later it was called L’Embarquement pour l’Isle de Cythère—the name under which another, somewhat different, version of the theme by Watteau (now in Berlin) had been engraved for Jean de Julienne, its owner and the artist’s close personal friend. As such it was described thereafter until 1961 when Michael Levey, basing himself partly on the melancholy which nineteenth- (but not eighteenth-) century observers detected in the paintings of Watteau, assembled some very telling evidence to suggest that the pilgrims were actually leaving, rather than setting out for, the island of Love.

This view accords well with what we actually see (the term of Venus has already been garlanded, the lovers have already been paired off), even if we refuse to recognize in the picture “an air of transience and sadness” and to interpret the gestures and physiognomies in the light of it. However, the arguments for a scene of departure are not decisive, and Posner rejects them, only to concur in the conclusion of some other writers that “‘going or coming’ is in any event irrelevant for understanding the picture”—a curious conclusion for someone who is so keen to demonstrate that “the meanings of Watteau’s fêtes galantes are far more explicit and more accessible than often thought.”

Even more curious is the surely meaningless (not to say desperate) claim of the exhibition catalog that “both interpretations are correct: the painting is as much a departure toward the isle as a departure from the isle”—a claim which is later glossed with the (perhaps necessary) comment that “Cythera is an ambiguous work that has given rise to and still engenders interpretations that could appear contradictory but are in reality complementary.”

In the exhibition in Washington the beauty of one picture soared above that of all the others (just as it inspires Posner’s most perceptive and eloquent writing)—the wonderful Shop Sign (in Berlin) which Watteau painted in order to “stretch his fingers” a few months before his death. In this quite exceptionally large picture we see a group of fashionable men and ladies inspecting the pictures and other objects in the shop of the art dealer Gersaint, the painter’s friend, while to the left a packer is crating a portrait of Louis XIV (the shop was called Au Grand Monarque). The scene looks real enough, though in fact neither the pictures nor the people nor the place corresponds to reality. Posner suggests that, in painting an ephemeral shop sign liable to perish through exposure to the open air, Watteau was—at the end of his career—in some way returning to his earliest years of penury; but returning to them in the light of his experience as a triumphantly acclaimed painter. “To make the very ordinary extraordinary by the magic of art must have seemed to Watteau a supreme exercise of the powers he possessed.” Above all, he could appreciate “with a sense of easy acceptance” the fragility of human life and artistic creation while at the same time demonstrating that art was “the very force that heightens the reality of life and dignifies human activity.”

Gersaint tells us that The Shop Sign was completed in eight mornings. It may be that this speed of execution was responsible for the picture’s excellent condition, for the saddest feature of the exhibition was the wretched state of so many of Watteau’s pictures—something that was already noticed in the eighteenth century and put down to his faulty technique. Despite the presence of some other superb paintings, many visitors must have felt—as did the artist himself and a number of contemporary admirers—that it was in his drawings that Watteau was really seen at his greatest.

We are told by Caylus and other friends that whenever Watteau “enjoyed a moment of freedom, on holidays, or even at night, he spent his time drawing from life,” and the exhibition provided a superlative selection of such works. But Watteau was not—as this quotation might seem to imply today—a purveyor of reportage. Only very rarely do his drawings record ordinary scenes from daily life. More often than not he drew single figures, sometimes in a variety of poses on the same sheet, and—with some very conspicuous exceptions—he usually omitted any setting or background for his figures.

As a rule it is not to Watteau’s drawings that we turn for an impression of the shops, the fairgrounds, the balls, the pleasures (or the miseries) of eighteenth-century Paris. But—and the point can hardly be exaggerated—the fluent delicacy of his style and his mastery of gesture and attitude rather than of physiognomy (how often he drew his figures from the back!) opened the way to other artists who were to eternalize just these fleeting moments of transient life. “The painter of modern life” whom Baudelaire was to find in Constantin Guys makes his first appearance with the incomparably finer Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, whose indefatigable recording of contemporary scenes led Greuze to comment that he had “un priapisme du dessin.” And Gabriel de Saint-Aubin’s exquisite, and yet spirited, drawings can hardly be conceived of without the precedent of Watteau.3

The Goncourt brothers, who had a very restricted view of eighteenth-century French art, claimed in their fine essay on Watteau that he was “the dominant Master who subjected all eighteenth-century painting to his manner, his taste, his vision.” Posner, like other recent art historians, reacts strongly against this and asserts—too emphatically—that “one may well question whether the history of French painting would have been significantly different without him.” Be that as it may, in another sense the impact of Watteau has surely been underestimated: it was given to him, as to no other single artist before or since, to enable much of his own century to see itself through his eyes—and for posterity to accept this vision as genuine.

This was made possible largely through the enterprise of his friends who (soon after his death) organized the engraving of the great bulk of his work—both his paintings and his drawings—so that the oeuvre of Watteau was probably more accessible than that of any other artist until the appearance of fully illustrated monographs in the twentieth century. It was not just specific details that could be imitated, plagiarized (and forged), but a whole style and a whole attitude to life that became available for inspection. And it at once became apparent that Watteau had been able to present the aristocratic, and would-be aristocratic, society of the ancien régime with an image of itself that was highly acceptable, however little relationship it bore to reality. In the words of someone writing within ten years of his death, “he painted the Figures finely drest in Gowns, and was the first who gave them genteel Airs, and not Stiff, as many did in Flanders, though otherwise theirs were well painted; such were called Conversations.”

Such was the reputation of Watteau as the celebrator of agreeable social occasions that Horace Walpole (who owned a picture attributed to him) could go on a musical picnic at Esher and see it as “Parnassus, as Watteau would have painted it”; and the Venetian Pietro Longhi who specialized in prosaic, not to say pedestrian, palace interiors could be described as “un autre Watteau.” By 1884 (the bicentenary of his birth) it had become absolutely standard practice for biographers to refer to him as “la personnification de ce XVIIIème siècle spirituel et aimable…” etc., etc.

And yet there was a problem, as many writers have emphasized. Watteau saw little enough of that “witty and amiable eighteenth century” for which so much nostalgia was felt during the period between about 1870 and 1920, when enthusiasm for the artist reached its peak. “There is hardly any period in the history of modern France quite as calamitous as the first decade of the eighteenth century,” as François Moureau points out in the catalog of the exhibition: “During his short life…Watteau witnessed a country almost continually at war, a territory invaded several times, his native Hainaut overrun with foreign troops, Paris threatened by siege and by an army rabble on the rampage”—and the dreadful winter of 1709 (the year of Watteau’s first successes) was marked by defeat, famine, and cannibalism.

For some historians these apparently inconvenient facts were almost welcome for they helped to dispose of the view propagated by Taine and his determinist followers that any artist was the product of three forces, “la race, le milieu, le moment.” And in the case of Watteau such disposal was particularly desirable because his “race” gave rise to the most complicated and humiliating embarrassment. There was no getting away from the fact that the Flemish town of Valenciennes had been ceded by Spain to France only six years before he had been born there; and yet how could one doubt that he was quintessentially French—that, in the words of one of his many patriotic biographers, “in Dresden, Potsdam and Berlin I have never come across Watteau without feeling refreshed by a breath of native air”? With Tainian theories out of the way, there remained the problem of how to account for the lyrical fêtes galantes produced under the most inauspicious circumstances. Fortunately, another formula presented itself. Watteau did not receive his sensibility or poetry from his own time. He “foresaw and anticipated” the Regency (il la devine, il la devance).

Ironically enough this was the very formula that had been used (for the first time, I believe) of the painter who had—temporarily, as it later turned out—obliterated the legacy of Watteau and his followers. As early as 1790 the genius of Jacques-Louis David was said (by David) to have “devancé la Révolution.” The full documentation about this—and a great many related issues—is to be found in Philippe Bordes’s extremely interesting book, which has recently been published in France. This will provide essential ammunition to both sides in an art-historical controversy which was first raised nearly two centuries ago and which has surfaced intermittently ever since: it is now raging with particular vigor.

Put in its simplest form (indeed in a form so oversimplified that it will lay me open to dangerous reprisals from all sides), the debate concerns the degree to which the canvases of David were politically motivated, consciously or unconsciously, or thought of as having political or social implications, before the outbreak of the Revolution. Because of David’s later career (his great painting The Death of Marat, now in Brussels, his vote for the execution of the king) it has inevitably been very tempting (irresistibly so for David and some of his admirers) to suggest that he had been antagonistic to the ancien régime well before July 14, 1789. And even after we have dismissed mystical theories about his gift of prophecy, the issues raised are of real importance and do not belong merely to the gossip columns of art history. For in stylistic terms no one has even disputed that The Oath of the Horatii (Louvre), painted in Rome in 1784-1785 and exhibited in Rome and Paris in 1785; The Death of Socrates (Metropolitan Museum), exhibited in 1787; and the Brutus…with the lictors bringing back the bodies of his executed sons (Louvre), exhibited in 1789, are among the most “revolutionary” pictures ever produced—for all the antecedents that have been ingeniously tracked down in recent years.

How natural then to claim that the grand austerity of their treatment of civic virtue was determined by rising bourgeois expectations, as used to be argued by some Marxist art historians postulating inevitable laws of stylistic change. Such “laws” are now somewhat discredited, as is the part once supposed to have been played by the rising bourgeoisie in preparing the ground for the Revolution. Moreover, some very inconvenient facts stand in the way of identifying David with “pre-Revolutionary” beliefs. In the first place, did any such beliefs actually exist? Second, The Oath of the Horatii was commissioned by the king, and its huge critical and popular success immediately led to David’s being given another important commission by the Court. Third, it has been shown that nothing in the antique subjects chosen by David before the Revolution had subversive implications. And, fourth, throughout these years David was also painting pictures for patrons who belonged to the most “reactionary” circles in France.

Some years ago Robert Herbert very convincingly argued that while the Brutus probably had no relevant political connotations when David began to work on it in 1788, it could certainly have acquired many as the crisis preceding the storming of the Bastille grew more alarming. More recently Thomas Crow has introduced two new elements into the discussion.4 He has claimed that the brutal, almost self-consciously clumsy, style of the Horatii of itself carried hostile overtones—not just to the prevailing artistic orthodoxies—regardless of subject matter, and that this explains why Beaumarchais’s polished Le Mariage de Figaro aroused far less antagonism than might have been expected. He has also demonstrated that some of the critics who did enthusiastically welcome this picture certainly could be associated with those embittered dissenters of the 1780s, many of whose careers and attitudes have been so thrillingly investigated by Robert Darnton.

All this (and very much more) has made it imperative to examine far more closely all the available sources that can throw light on David’s personal and political affiliations before he became involved not only with the early stages of the Revolution but also with its later, more extreme, manifestations. This is what Bordes’s book sets out to achieve, although he begins his story only with the triumphant aftermath of The Oath of the Horatii and devotes the main part of it to the genesis of just one painting which was never completed, The Oath of the Tennis Court (now at Versailles).

Bordes makes his own view clear enough. He presents us with a David who, although he was welcomed everywhere and although (as was natural enough under the ancien régime) he was ready to paint for patrons of all kinds, fairly soon found one circle particularly congenial. This was not (as has so often been suggested) the group around the Duc d’Orleans, which was bitterly hostile to the court at Versailles—though David certainly had close contacts with some members of the duke’s entourage. His real friends were the Trudaine brothers (for whom he painted his masterpiece, The Death of Socrates). Their salon brought together many men of liberal sympathies of whom the most notable was André Chenier, later to be guillotined. David and Chenier were very close for a number of years, and Chenier dedicated a poem to him, as he was to recall after their break in 1792: “Du stupide D[avid] qu’autrefois j’ai chanté.”

David was probably also in touch with Thomas Jefferson (a great admirer of The Death of Socrates) and was certainly very friendly with Filippo Mazzei, who had gone to America to take part in the War of Independence (and whose portrait by David was reproduced a few years ago on a forty-cent stamp). Other members of the same circle were the artist Maria Cosway (to whom Jefferson wrote his famous love letter, “My Head and My Heart”) and John Trumbull, who was engaged in painting The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown (Yale University Art Gallery). The general pattern seems consistent enough, and Bordes argues that, although like all the members of his group—not to mention countless other men and women throughout France and the world—David welcomed the fall of the ancien régime, his commitment to politics had not gone any further than that when it occurred. Only some three years later did he break with his old friends and move, hesitantly at times but ruthlessly, toward Robespierre and the left.

Bordes’s book, though short, is very fully annotated, and because of the issues I have raised here, it is bound to be analyzed with a rigor worthy of nineteenth-century higher criticism of the Bible. Before this gets fully underway, I will mention one curious omission, not because it is particularly relevant to Bordes’ argument but because it continues to cause unnecessary confusion. He reprints in full the French text of the much-discussed letter (known only at second hand) said to have been written by Sir Joshua Reynolds to the press describing the impact that The Death of Socrates had made on him at the Salon: “the greatest artistic achievement since the Sistine Chapel and Raphael’s Stanze in the Vatican.” But (like virtually everyone else who has referred to this mysterious communication) he fails to investigate whether Reynolds actually went to Paris in 1787. In fact, it seems almost certain that he did not, and the document was probably a deliberate concoction designed to give backing to David’s hopes (first published more than fifty years ago, but not mentioned here) of exhibiting at the Royal Academy in London.

More to the point, it must be said that while Bordes squeezes to the utmost any evidence that supports his thesis, he is somewhat less concerned with those nuances that conflict with it. The revisionists (or are they counterrevisionists by now?) will certainly feel that there is more to their case than appears here; and indeed one is sometimes driven to wonder whether there is any historian in the world who would be prepared to examine the precise nature of David’s political commitments without feeling that his own personal integrity was at stake. Nonetheless, Bordes’s book is an important one about an important subject that will continue to arouse interest as well as passion.

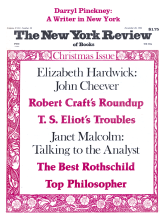

This Issue

December 20, 1984

-

1

“A Corner of the Last Judgment,” in Daedalus, vol. 109, no. 2 (Spring 1980), p. 210.

↩ -

2

“If worst comes to worst, isn’t there always the charity ward? They turn away no one.”

↩ -

3

Watteau’s contribution to another essential feature of eighteenth-century art—rococo decoration—is carefully assessed in the extremely important book by Marianne Roland-Michel, Lajoue et l’Art Rocaille—which has recently been published, in Paris (Arthena).

↩ -

4

Art History, vol. 1, no. 4 (December 1978).

↩