Jean-François Revel believes that the democracies are in imminent danger of collapse, because of a failure of will, and of intelligence. According to him, the democracies neither understand the nature of the Soviet threat nor possess the will to resist it. The Soviet system, as represented by this author, combines the grossest incompetence, in the management of its own economy, with the most farsighted logic in the conduct of its foreign policy. The democracies, on the other hand, have combined great success, in economic affairs, with abject failure in the domain of foreign policy. So the Soviet system is doomed through its internal failures, but before it collapses, the logical continuity of its foreign policy is likely to destroy the democracies. As M. Revel puts it, in the concluding words of his fourth chapter, “Survival of the Least Fit”: “Communism may be a ‘spent force,’ as Milovan Djilas has repeatedly said. Some might even call it a corpse. But it is a corpse that can drag us with it into the grave.”

Much of How Democracies Perish consists of peremptory (and repetitious) affirmations studded with striking images, like the bit about the corpse. As a writer, M. Revel is an heir to Rousseau, that master of “seismic slogans” (J.H. Huizinga’s phrase). Still, also like Rousseau, M. Revel does argue, part of the time, and even produces evidence; although the ratio of evidence to affirmation and phrase making is quite low, and the quality of the evidence not always high.

M. Revel’s best chapter, the one that contains the most argument, and is the core of his reasoned case, is Chapter 6, “After Poland: An Autopsy.” The chapter begins with a Western summit held at Versailles, in June 1982, six months after the declaration of martial law in Poland. At that June summit, the Americans asked the Europeans to raise their interest rates to the Soviet Union, denying them the preferential rate usually accorded to poor countries. The Europeans refused, arguing that higher interest rates would not improve Soviet behavior in international relations. M. Revel goes on:

So, after a dozen years of pleading that economic aid to the East bloc would pacify the Soviet Union, the Europeans in 1982 declined to reduce that aid because it would not make the Russians less belligerent. Incoherence on a grand scale! Economic cooperation did not bring the hoped-for détente, but neither would non-cooperation. That’s a fine, blind maze we’ve shut ourselves into; appeasement and reprisal, we find, are equally incapable of making the Communists behave themselves and of slowing their aggressive drive. By this reasoning, our only choice is whether we’re going to pay to be rolled, and we are opting to die paying.

M. Revel reproaches the West for responding to martial law in Poland by showing their own “unshakable determination to live up unilaterally to their Helsinki commitments [of 1975] without so much as pretending to ask anything in return.” And M. Revel sets out—by implication—how he thinks the West should have responded to martial law in Poland:

Obviously, the democracies could not dream of making the slightest show of armed force. The problem was what it has always been: how to use the economic and political means we have to moderate Soviet policy. Such tactics have never, to my knowledge, endangered the peace, whatever is said by Westerners toeing the Communist line. In fact, they perfectly fit the definition of peacetime diplomacy. No one can be accused of warmongering because he seeks to suspend or curtail favors that are never repaid. Consequently, the only real question after the December 13 declaration had nothing to do with military posturing. It was whether the democracies were going to consider the Polish declaration as intolerable and end the era of unilateral Western concessions. There would have been nothing wild or dangerous in such a stance; in dealing with a Communist world tormented by its inner contradictions, it might even have been reasonably effective.

That is not a negligible case. But whether or not you can accept it depends—in part at least—on one of these peremptory affirmations of M. Revel’s: “[The Soviet Union, in Poland] was contending with a peaceful revolution it could not put down by any of its usual methods.”

Could not? How can we know that? We know that the Soviet Union did not deploy its tanks and other forces in Poland in December 1981, or since. It preferred indirection and Polish martial law. But preference does not mean that the alternative rejected in December 1981—direct intervention—was impossible then, or has become impossible now. The Soviets chose Jaruzelski, and martial law, that December, rather than direct intervention. But how if Jaruzelski should fail, in their opinion, to stop the rot: Poland’s tendency to slip out of the Soviet orbit? Would they apply their ultimate sanction: direct intervention? M. Revel does not adduce any argument—in support of that flat “could not”—that would suggest a likelihood that the Soviets would accept the development of Polish independence, rather than intervene directly. It seems probable in the circumstances—and especially because of Poland’s geographical position between the Soviet Union and Germany—that the real alternative to Polish martial law was not Polish independence but Soviet intervention.

Advertisement

If we take account of that dimension, it does not appear that the Western reaction to Polish martial law was necessarily as craven or as callous—or as “doomed”—as M. Revel represents it. If Soviet direct intervention remained a real possibility—pace M. Revel—the West might surely be justified in keeping its limited panoply of sanctions in reserve for that emergency. The availability of those sanctions might increase Soviet hesitations about intervening and offer a limited, marginal protection for the Poles. To expend sanctions against martial law would have reduced Soviet inhibitions about replacing martial law with the more thoroughgoing expedient of Russian intervention. Western economic sanctions would have been used up; and Western military sanctions are not a realistic option—as M. Revel appears to admit.

Of course, it is impossible to know how much thought the Western governments gave to the interests of the Poles, as a factor in the calculations. The calculations of the Western governments were necessarily dominated by their conception of their own selfish interests: that is the case with all governments, at all times. But the calculations of democratic governments—much more than those of nondemocratic governments—involve an obligation to look good to their own people. And it would be difficult for Western governments to look good, while the Russians were crushing the Poles, if the Western governments had no sanctions in reserve, other than the impossible military one, to apply to the Russians.

So if the Western governments did not respond to the Polish crisis in the way M. Revel thinks they should have, it is indeed probable that, as M. Revel believes, they were acting selfishly. But it does not follow that their course of action was necessarily at variance with the interests of the Polish people. There are probably few Poles who would prefer Russian occupation to Polish martial law. Clearly the Catholic Church in Poland does not entertain that preference. And the Polish bishops have quite possibly a better idea of what Poles can realistically hope for than M. Revel can have, or than I can have.

M. Revel quite rightly discounts much of the anticommunist rhetoric of Western statesmen. They are all ready, as he shows, to do a deal with the Communists at any time, if there is money to be made, or votes to be won. Witness the European deal over the Siberian pipeline; witness Ronald Reagan’s sales of American grain to “the evil empire.” Interest prevails over rhetoric, every time. True, but is this necessarily a bad thing? Would the world be a better place, and would democracy in particular be in better shape, if President Reagan consistently pursued the line indicated by his own anticommunist rhetoric, and never compromised—with an eye, for example, to regional interest groups, and the electoral prospects of himself and his party?

M. Revel’s argument assumes, throughout, that the answer to that question ought to be a resounding “Yes!” In his view, real and consistent economic pressure on the Soviet Union would induce it to behave better—pull out of Afghanistan, relax its pressure on Poland, etc.—or face a collapse, which only Western aid staves off.

That seems a large assumption. It may be correct. Who knows enough about Soviet decision making to be sure? Is it not at least equally possible that a Kremlin under such pressure, and facing the possibility of internal collapse, might respond with a willingness to run far higher risks, in its defense and foreign policy, than anything yet seen?

As between the optimistic Revel assumption, and the alternative pessimistic hypothesis, I think prudent democratic statesmen would be justified in declining M. Revel’s advice. They will probably decline it in any case, both for short-term reasons of interest, and because of a practical politician’s lack of confidence in long-term political prophets. Democratic politicians—as indeed M. Revel points out—are not, and cannot be, foreign-policy chess players. (And M. Revel’s one chess metaphor—on page 35—suggests that he is not a chess player either.)*

Confidence in M. Revel’s argument is not increased when he takes his illustrations from outside Europe. Take, for example, his treatment of the Middle East. In this region, as elsewhere, according to M. Revel, the Soviets have been steadily gaining, and the West losing. As he says in Chapter 11, “Long-range Vision and Hindsight”:

Advertisement

If Soviet diplomacy is successful, it is not because the men in the Kremlin are endowed with any particular genius. It is because they stick to a method that includes the principles of long-term continuity of action, constant review of the reasons for that action, and acceptance of the fact that solid, irreversible results can be slow in coming. On the other hand, Western diplomacy, however intelligent its practitioners (intelligence that, more often than not, shines outside of politics), is discontinuous. Leadership changes frequently, and the new teams tend to forget or mistrust the reasoning behind their predecessors’ decisions. And the democracies’ diplomacy is guided by a need to feed public opinion with quick, spectacular results. The upshot of all this is that Western diplomacy is more easily led by the nose than Soviet diplomacy is. Moscow wins the advantage over the long haul, a fact Westerners refuse to believe; to them, the idea that everything the Soviets do is the fruit of long-term calculations is a sign of paranoia. For example, in 1974, during the first oil crisis, and in 1980, after the invasion of Afghanistan, it was considered bad taste in the West to suggest that the Soviets might be trying to weaken Western Europe indirectly through its dependence on Mideastern oil.

Yet in Andrei Sakharov’s book My Country and the World we find the following passage referring to a period well before the oil crisis, before the Soviets took control in South Yemen and Afghanistan and began the process of destabilizing the Persian Gulf emirates and Saudi Arabia. “I often recall a talk given in 1955 by a high official of the USSR Council of Ministers to a group of scientists assembled at the Kremlin. He said that at that time (in connection with a trip to Egypt by D.T. Shepilov, a member of the Central Committee Presidium) the principles of the new Soviet policy in the Middle East were being discussed in the Presidium. And he observed that the long-range goal of that policy, as it had been formulated, was to exploit Arab nationalism in order to create difficulties for the European countries in obtaining crude oil, and thereby to gain influence over them. Today, when the world economy has been disorganized by the oil crisis, one can plainly see how crafty and effective is the subtext of the oil policy (‘defending the just cause of the Arab nations’)—although the West pretends that the USSR has played no role in the situation.”

M. Revel adds that it was he who italicized the words in the Sakharov quote in order to bring out “how long the plan was in the works before it bore its first fruit in 1973, the clarity of its conception, and the high level of the meeting at which the analysis was made—in the Kremlin itself.”

Fair makes your blood run cold. “In the Kremlin itself….” Br-r-r!

On closer inspection, however, one or two little flaws begin to appear. The Yom Kippur attack was preceded by Sadat’s expulsion of the Soviet advisers. Was that part of the Great Design of the chess grandmasters in the Kremlin? If it was, the move should be marked with a point of exclamation. There is a touch of Morphy—the most flamboyant of chess masters—about the notion of the Kremlin’s instigating an expulsion of Soviet advisers: sacrificing a castle for a decisive positional advantage….

So far, so good. But was the decisive positional advantage actually obtained? There is some reason to doubt that it was, since the peace process after the Yom Kippur war was conducted entirely under American auspices, with the Soviets helpless on the sidelines, and culminated in a separate peace between Egypt and Israel, with Egypt passing into the American camp….

The same Egypt that eighteen years before had been the center of anti-Western propaganda in the Middle East, and apparently the newest, brightest jewel in the Soviet crown! That was in 1955—the year, remember, when the Great Game began, “in the Kremlin itself.”

It reminds me a bit of an episode in recent Ghanaian history. A coup had taken place and a gentleman who claimed to have “masterminded” the coup rushed back from London to Accra to take his place at the head of a grateful nation. That same evening, the poor man appeared on Ghana television, with submachine guns leveled at his head. An interviewer asked him: “Are you the man who masterminded the coup?” The interviewer replied with appropriate care: “I did mastermind a coup, but it seems that the coup that has actually taken place is not the coup that I masterminded.” History is often like that.

It is true that the Yom Kippur war was accompanied and followed by action severely damaging to the Western economy: the use by the Saudis and others of the so-called “oil weapon.” No doubt the Soviets were pleased with that development, and no doubt they had long hoped that something of the kind would happen. But what reason is there to suppose that they actually brought it about?

The most parsimonious hypothesis to make about the actions of the Saudis, etc., as about those of other potentates, is that they act in their own perceived self-interest. It was very much in their interest, at that time, to raise the price of oil. It was also in their interest to time and legitimize their action in tune with Arab nationalism. Principle, profit, and prestige all concurred, in 1973. No dilemma there, or need to suppose a Soviet plot.

In 1982, however, when principle and prestige pointed one way, and profit the other, the Saudis and their associates opted firmly for profit. The Israeli attack on the PLO in Lebanon was a far greater outrage against Arab nationalism than Yom Kippur could be (since Yom Kippur had been an attack by Arabs against Israelis). Yet there was no question, this time, of the use of the “oil weapon.” There was an oil glut. The Saudis, etc., acted unwaveringly in accordance with their own interests. There seems no reason to suppose either that they had been more quixotically inclined back in 1973, or that they were at any time pawns on a chessboard set up in the Kremlin.

M. Revel throughout supposes that the democracies are at a permanent disadvantage, in the conduct of foreign policy, as compared with the Kremlin. Many officials, in the foreign offices of the West, are strongly of the same opinion: indeed it is quite a useful professional alibi, when things go wrong.

Yet the supposed advantage of the Kremlin is merely a guess, and can be no more. We know all—or at any rate a lot—about the incoherences and improvisations of democratic foreign policy, the demands of interest lobbies, the simplifications of television, etc. But about the Kremlin’s decision-making processes, we can only guess. M. Revel has a perfect right to his own guess, though it might be better if he presented his guess a bit less dogmatically and dramatically.

Let me end my review by setting up my own guess, about Soviet foreign policy:

The guessing starts out from one premise which I take to be a certitude. The “chess” metaphor—which is implicit throughout M. Revel’s argument, though-explicit in only one place—has to be misleading. In chess, the moves, on each side, are planned by one person, animated by only one purpose: winning the game. The notion that the foreign policy of either superpower today can be conducted like that seems to me romantic. Soviet foreign policy today, at any rate, is conducted by a bureaucracy. Bureaucracies play all sorts of games, within themselves, but they don’t engage in a straightforward, single-minded, collective game of chess—one for all, and all for one—against an outside party. Adversarial games go on within the bureaucracy itself, between ambitious people, for whom the real enemy is not the outsider, but the rival for promotion, within the same bureaucracy. Such rivalries exist in all bureaucracies but it seems a reasonable guess that they are likely to be particularly intense in the closed, hierarchical, centralized Soviet system: the pressure cooker of the Kremlin.

What role does ideology play in all this? Here we are indeed guessing. M. Revel’s guess seems to be that ideology—in the sense of promoting world revolution—is dominant. My own guess is that ideology provides the language, the concepts, and the counters through which internal struggles for power are waged between interest groups and among rival individuals making use of interest groups. The appearance of strict Party orthodoxy has to be a competitive asset, within the system, and this factor seems likely to affect foreign policy, on the whole adversely.

Since I am guessing at this point, let me present a hypothetical scenario, concerning the Politburo’s decision to invade Afghanistan.

Suppose that most of the Politburo knew that the invasion of Afghanistan was a stupid idea: unnecessary and costly. But some members also knew that it might be profitable for them, in terms of perceived Party orthodoxy, to advocate such a move (“nipping counter-revolution in the bud”). Others knew that it might be risky to oppose it, for similar reasons. Still others may have had more subtle calculations. Bureaucrat X may think it crafty to express his reservations, but not to press them, letting himself be overruled by Bureaucrat Y. In that way, when the damned thing goes wrong, X will look good, and Y bad, which is the object of the decision-making process, as Bureaucrat X sees things.

That may be the way it works, at least some of the time. As a guess, it seems to me to have the advantage, over M. Revel’s, that it supposes the Kremlin to be inhabited by human beings (of the bureaucratic subspecies) and not some icily logical collective brain.

M. Revel is being presented, it seems, as the intellectual successor to the late Raymond Aron, the eminent French foreign affairs analyst. If that were so, it would be a symptomatic corroboration of M. Revel’s thesis: democracy in decline. But it is not so. M. Revel is a different kind of being from Aron, who was a political thinker (like Walter Lippmann). M. Revel is a prophet, who thinks only in short intervals, in between being carried away by his own visions. Reading him, I was often reminded of Camus: bad Camus, the eloquent certitudes of Camus’s cold-war journalism, and the vision of the war in Algeria as fomented by “the imperialism of Cairo,” with behind it the Kremlin.

That kind of stuff, it seems, is back in fashion. It is a pity, and a source of weakness, not strength, to democracy. In present conditions, M. Revel’s vision helps those Americans who want to intervene in Nicaragua. And the people who are likely to benefit most from such an intervention are the very people whom M. Revel is warning us against.

Perhaps M. Revel should take time off to reread some good Camus. I would recommend La Chute, the story of the penitent judge.

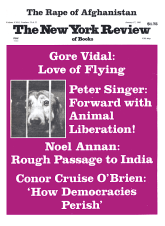

This Issue

January 17, 1985

-

*

The Revel chess metaphor: “In this chess game, the USSR is always playing white, with the advantage of the opening move; when it’s black’s turn to play, all the West does is make a clumsy sweep that wipes the board clean.” Wiping the board clean would be difficult to accomplish in a single move (“black’s turn to play”). Perhaps it is M. Revel’s translator who is at fault here.

↩