A lot of Gregor von Rezzori’s autobiographical novel is about the overwhelming difficulty of getting it written and how it was begotten by despair upon impossibility. In the end (if it is the end: the English, though not the original German, version finishes with the legend END OF BOOK ONE) it runs to 632 pages. You need to think big about it: think of terms like epoch (1918–1968), epoch-making, Gargantuan, Promethean, apocalypse, holocaust, maelstrom, Götterdämmerung, Wirtschaftswunder, The Decline of the West, A la recherche du temps perdu, the mega-Mann of The Magic Mountain, Dr. Faustus, and The Confessions of Felix Krull. At times you may think it is a case of overkill, especially in the hall of sex where every dazzling trophy on the wall is a grand twelve-pointer, whether she be a Francophone mulatto impresario, a freaked-out WASP model, rich Romanian Jewish femme du monde, poor Polish Jewish concentration-camp survivor, French hooker, German hooker, German Hausfrau, German aristocrat, German movie starlet, or French movie star. Sexual boasting is matched by cultural boasting, with classy quotations in every European language dropping like crystals from a chandelier in an air raid. And all this is delivered by a Torvill and Dean of the typewriter, dancing the zapateado upside down on ice.

Though less so in the feeble English translation by Joachim Neugroschel. This lurches from fourth-grade literalness to vulgar banality (and not just when Rezzori mimics, as he often does, the jargon of some modern hate-world of his, like public relations). It ranges from the quaintly archaic “tiding” for “message” to plain ignorance, like “Lake Wörther” for “Lake Wörth.” People pout when they should be sulking—the activities can overlap, and one word does for both in German, but not in English.

Even in translation, though, Rezzori’s alter ego buttonholes you, convinces you that what he has to say is not just important but vital, your great, your last, your only chance of understanding what happened in and to Europe between 1918 and 1968. Scourging hype is one of his favorite activities, and yet one wonders every now and then whether one isn’t falling a victim to his own hype as he preens, puns, parries, parodies, pirouettes, pontificates, and prophesies in a selection of typefaces according to whether the first-person narrator is narrating, thinking, writing a letter, or apostrophizing his dead friend Schwab, a failed novelist.

It will be obvious by now that the verbal exhibitionism is catching. But the important thing is that Rezzori has something to exhibit besides his extravagant dexterity with words and conjurer’s sleight of hand at transforming idées reçues into revelations: he is amazingly funny, clever, committed, and his chutzpah is of a transcendental order—in spite of (or possibly because of) the fact that here, as in his earlier Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, he specializes in not being Jewish and illuminating anti-Semitism from the inside.

His hero is born just after the First World War in Bessarabia, supposedly the son of a local landowner with a passion for field sports. His promiscuous mother is the child of an Austro-Dalmatian family hovering between petite bourgeoisie and petite noblesse without ever brushing against the haute bourgeoisie. This lovely poule de luxe follows the café-society seasons with her little boy from St. Moritz to the Cap d’Antibes to the Scottish grouse moors. Her lovers include an Armenian oil magnate, a Bolivian tin millionaire, both not too thinly disguised real personages, and a Romanian prince of Byzantine extraction who is probably the narrator’s real father. Urbane, humane Uncle Ferdinand is a repository of the values of a dying aristocratic age, and he passes them on to his putative son. These values, originating in medieval chivalry, were not extinguished in the early twentieth-century plutocrats. Though their blood was not blue, Armenian Uncle Agop Garabetian and Bolivian Uncle Bully Olivera were aristocrats—uninhibited, generous, brave, and free from envy. The bad new age begins with the rise to power of the petite bourgeoisie whose sole motivation is mean, resentful jealousy. This idea is an important thread in the novel and not difficult to keep hold of.

Between trips to the playgrounds of Europe, the little boy grows up in remote, unspoiled Carpathia, where the forests are full of game, the peasants real peasants, and the tea, bath soap, and nanny of the finest English quality. Rezzori’s descriptions of the countryside throb with the verdant, flat-out, heart-stopping lyricism of German romantic poetry and are among the best things in the book.

The Arcadian period ends with his mother’s suicide. He is sent to Vienna to be brought up by her sister. Aunt Hertha and her husband Uncle Helmuth belong to the disappointed, disgruntled post-1918 middle class, the seedbed of Nazism, which—along with spiritualism—they embrace even before the Anschluss.

Advertisement

They live in a poky flat, scrimping, keeping up appearances, and hating equally the classes above and below their own: the poor for being dangerous lumpen proletarians, and the rich because they are undeserving, immoral, and irresponsible. The narrator detests his uncle and aunt and their priggish son Wolfgang with whom he has to share a room until he is nineteen and Stella comes along and sets him up in a garçonnière. Stella is an intellectual heiress, a Romanian Jewess married to a British aristocrat in the diplomatic service and formerly one of the narrator’s mother’s lovers. John is the best mannered of maris complaisants. Like Uncle Ferdinand, he and Stella have a set of values to teach the hero—an avant-garde disdain for the obvious in life as in art. Stella is captured by the Nazis when she makes a foolhardy trip to Germany for a last meeting with her young lover. This is in 1940, by which time the narrator has succeeded in joining the Romanian rather than the German army, thereby making sure of a comparatively safe war.

After it he attends the Nuremberg trials as a witness in the case against Stella’s concentration-camp murderers. He meets his future wife Christa there in the court-house canteen where she is wolfing as much American food as she can get down. This gorgeous blonde is an East Prussian aristocrat by birth but a mean-minded bourgeoise at heart. The young couple set up in a bombed house in Hamburg. For the next two years it seems always to be winter, with the water frozen solid and the potatoes frozen black. Christa complains while her husband dreams banal dreams about Germany’s future, with a group of intellectual cronies. To feed Christa and their baby son he goes to work as a script-writer for the “movie piglets” of the renascent German film industry.

The marriage breaks up but the despicable and despised job goes on: he has to earn the money for Christa’s alimony, their son’s education, and his own “partridge and Mouton Rothschild” habits. He resents it bitterly, because it stands in the way of the great book that he knows he must write:

I want to say everything in this book: everything I know, presume, believe, recognize, and sense: everything I have gone through and lived through; the way I have gone through it and lived through it; and, if possible, why and to what end I went through it and lived through it.

Like The Death of My Brother Abel, his book, of course, has to be about

a man who wants to write a book about a man who wants to write a book about a man who wants to write a book…and this diabolical circle is our case, dear friend: we dash around in it in a ring like rats in a trap, without ever reaching each other; and when we ask about the meaning and purpose of the whole business and what impels us to ask about a meaning and purpose, then we really get into a maelstrom. But, whatever, I am nothing but my story. And this story is my book. So I can say: I am my book.

The dear friend to whom this passage is addressed is Schwab, the failed novelist. He works as editor for a German publishing tycoon, and persuades him to pay an advance on the hero’s unfinished novel. It is really Schwab’s novel too, but he has been unable to write it. In a sense he dies of it, drinking himself to death as he urges his friend on with the great work. He is as stiffly and uncomfortably German as Rezzori is cosmopolitan and nimble. He is not a survivor. Rezzori is. And, according to one possible exegesis of this intricate text, surviving is a form of murder. In any case, Schwab is cast as Rezzori’s brother Abel, his conscience and his victim; besides, he is not a real person, but a fictional creation by the fictional Rezzori.

The book ends with Rezzori delivering the funeral address over his coffin. But since the narrative leaps backward and forward between the present (1968) and various layers of the past, the hero and the reader know of Schwab’s death long before the end of the book. As soon as it occurs, the hero begins to suffer a recurrent nightmare in which he has to murder a terrible crone (probably a descendant of Raskolnikov’s victim) because she knows of another murder—Schwab’s—that he has committed, even though he himself has no recollection of it.

The novel Schwab and Rezzori are bent on creating is a grimly determinist work, written by the Zeitgeist whose helpless creatures they are:

Advertisement

As redeemers or wanton strivers, as geniuses or run-of-the-mill morons, we are tiny particles of some collective whole whose will we carry out—thereby fulfilling its destiny. None of our gestures can be dissociated from these states and currents, which furrow us like a wheat field in the wind—in the wind of the Zeitgeist.

But the Zeitgeist also imposes a terrible anxiety on the writer: he must be first with its message:

You can be sure that when you have an idea that is extraordinarily interesting because it is new and previously unuttered, at the same moment several dozen equally clever men all around the globe are having the same notion…a good dozen other authors of the masterpiece of the era.

…And he who wishes to hear the mystery of the Zeitgeist, that which says itself through us but is not yet named—he who wishes to name it must make himself so taut that sooner or later he will snap…. When our throats tighten with fear lest we are late with everything, forgotten by our Zeitgeist, never its mouthpiece, when we are epigoni after all, adding only frills, unable to say anything fundamental to our era, then our situation will affect our mind, dear friend. No one could be more aware of this than you.

The you, of course, is once again “my brother Schwab, and he took the logical consequences and kicked the bucket.”

The chronicle dictated by the Zeitgeist has three turning points: the first is March 12, 1935, the day of the Anschluss, “the day the sun stood still,” an obscene event, “a tremendous mass coitus”; the second is the Nuremberg trials; and the third the German currency reform of 1948. The first marked the end of an era of acceptable values and ways of living and “amputated” the early half of the hero’s life; his perpetual reminiscing is an attempt to recover that half and the undamaged person he was before he became a displaced person. The last turning point, the currency reform, ushered in the age of bullying materialism, with greed and petty bourgeois manners and morals spread like margarine over all layers of society. Like Evelyn Waugh, Rezzori writes worst when he loves (especially, in Rezzori’s case, when he loves women) and best when he hates.

He hates himself, though less than you might think when you consider he has stamped himself with the mark of Cain. But otherwise his hatred is on a Swiftian scale, and he hates a lot of things the reader can happily hate along with him. He hates hype, hypocrisy, consumerism, snobbery, the “media,” the film industry, the ruin of the countryside, the phony preservation of the countryside with restored cottages inhabited by pop stars and film writers, the Americans for being crude, the British for being smug, the Germans for being greedy and wordy, unincinerated Jews like his New York-Romanian agent Brodny for surviving so sleekly, the Austrians for being the eagerest Nazis, and the self-contained French—with more envy, really, than hatred—because through their peculiar attachment to their language they have preserved a glimmer of individual culture amid the standardization of the rest of Europe where, from your car window, there is no way of telling whether you are driving through Hamburg, Seville, or Detroit. “Maggots teeming in the carcasses of cities” have crowded out the dream of “ANTHROPOLIS” which he and Stella and John used to try to inhabit.

As for the Nuremberg trails, they demonstrated that mass murderers are quite ordinary people and humanity a trivial bunch unable to deal with enormity. Listening to the interminable speeches of prosecutors, defendants, and judges, the narrator reflects that

the dreadful thing, the ridiculous thing, the poignant thing about the Nuremberg Trial is that it is built upon claptrap and has nothing else to put forward but simply claptrap. It is the desperate attempt at inflating the claptrap on which our civilization rests, the noble, sad, quixotic tilting of Western fictions at the windmills of the reality of human nature.

Standing over Schwab’s coffin Rezzori addresses his alter ego’s alter ego:

Nothing more was happening to us. There were no murderers anymore and no victims, because there was no more human reason able to distinguish between good and evil. Madness was growing hybridly, welling and swelling and forming metastases like everything else around us. There was no more guilt and hence certainly no more atonement, hence no destiny and thus nothing more to narrate. We should have known this, my brother Schwab. We shouldn’t have pushed one another to write. Why? For whom? To what end? Peace could have been with us long ago, my brother Cain.

But what makes him Cain?

—afflicted with most annoying of all birth defects, which arouses no pity like other strokes of stepmotherly Nature, such as a cleft palate, for instance, or a harelip, or other bizarre deformations and malformations: a hump, a hydrocephalus, all kinds of nervous and mental ailments, cretinism, falling sickness, and the like. No, indeed. This is a far more repulsive handicap, evoking arbitrary hatred against people who are totally different, fundamentally alien:

the mark of Cain: existential consciousness

stamped on those who are condemned to recognize in themselves not just any human being but man per se.

Still, in spite of his words to the dead Schwab, Cain/Rezzori has produced his 632 pages, and they might just possibly turn out to be “the novel of the era” as he wanted them to. He has taken nostalgia for the past, one of our maladies du siècle, and turned it into a metaphysical ache. His novel is not War and Peace, or Buddenbrooks, or Ulysses. It has no characters and so it will be difficult to remember. The men in it are bundles of opinions, the women deplorable sex objects snipped out of glossies. But the reams of existential-anthropological-sociological-psychological brooding never get boring; mounted on the fabulous beasts of Rezzori’s grotesquely inventive imagery, you are carried along like a child on an accelerating merry-go-round until your head spins and you feel exhilarated or sick; or both.

You cannot help admiring the undertaking itself. The way Rezzori has structured it seems right, and in his characteristic metaphorical manner he describes the structure better than anyone else could:

This sort of thing should no longer be presented in linear form, can no longer be presented chronologically…. My space-time is an island in the ocean of time. My reader is with me on this island, which still lies in the dark for him. He wants to get to know it—by all means. My story sweeps across it like the beam of a lighthouse. It sweeps along the horizon all around my island, always sweeping across the same areas; but each time the light beam seizes them, they expose something previously unknown, until eventually the entire topography is experienced.

So the same scenes recur again and again: the night drives from Germany to Paris where the author holes up in a sleazy hotel to get on with his masterpiece in time stolen from the movie piglets; Gaia (the mulatto) dying of cancer; Dawn (the model) eating the white roses the author has given her before she chucks him; Schwab sweating in the Paris heat because the case with his summer clothes has been lost at the airport. And the big scenes: Hitler marching into Vienna; the postwar journey to Nuremberg across devastated Germany, a country of starving refugees, cripples, mourners, and child prostitutes, their misery thrown into relief by the American soldiers fatly filling out their smooth uniforms. Rezzori’s prose is up to epic mass scenes, which he tackles in the style of Abel Gance rather than Cecil B. De Mille. If someone commits the irony of turning The Death of My Brother Abel into a giant spectacular movie, one hopes the director will be of that caliber.

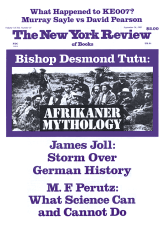

This Issue

September 26, 1985