In response to:

Passage to Palestine from the September 26, 1985 issue

To the Editors:

I was sorry, indeed surprised, to learn that in his review of my book Palestinian Leadership on the West Bank [NYR, September 26] Avishai Margalit missed, or rather misread, my main thesis. Contrary to his contention, I did not depict these Palestinian leaders as “moderate” but as “nationalistic,” “radical,” “militant,” and “pro-PLO.” Yet at the same time I maintained that most of them were pragmatic and realistic leaders who wish to coexist peacefully with Israel. They have also been, so I argued, authentic representatives of the West Bank Palestinian national community, having led it through an agonizing struggle against Israeli occupation. Consequently, “they might serve, for example, as useful intermediaries between Israel and al-Fath or form the leadership of a future Palestinian entity within or outside…a Jordanian Palestinian federation or confederation” (pp. 208, 209).

It is true, as Margalit observed, that “by the time Ma’oz finished writing his last chapter [March 1983] it turned out that all but one of the mayors he deals with were no longer mayors.” Yet it is equally true that most of these mayors, like their fellow urban leaders, still constitute key partners, alongside Arafat and Hussein, for an Israeli-Palestinian-Jordanian settlement. In fact, the kind of settlement advocated in my book, namely a Palestinian-Jordanian confederation coexisting with Israel was, as it turned out, later adopted within the Hussein-Arafat agreement of February 11, 1985. The principles of this agreement were subsequently also accepted by most West Bank Palestinans, by many Israelis, as well as by Egypt and the United States. If all these parties subscribe to such a settlement, on what grounds does Margalit so sarcastically dismiss it? Can he suggest a realistic and workable solution that will be accepted by all these parties, notably Palestinians and Israelis?

To be sure, one of the crucial issues on which such an agreement depends is not whether Arafat would shave his “ominous four day beard” (as Margalit put it) but whether or not he would be prepared to explicitly recognize Israel’s right to exist in accordance with UN resolutions 242 and 338. Margalit rightly mentioned that Ben Gurion in the 1930s made an attempt to meet with Arafat’s historical predecessor, Hajj Amin al-Husayni. However, Margalit fails to add that al-Husayni refused to talk to Ben Gurion. Would Arafat be willing to talk to Ben Gurion’s successor Shimon Peres?

This brings me finally to Margalit’s critical remarks that Hebrew University professors, who function as Arab affairs advisers to the Israeli government, have a “powerful” role in West Bank life and serve the military-intelligence establishment which is attached to the Labor Party.

Speaking for myself, I served as adviser under the first Likud government, hoping to influence its policy towards reaching a peaceful settlement with the Palestinian community in the West Bank and Gaza. My boss, Defense Minister Ezer Weizman, did not need any convincing, but Premier Begin did not agree to talk to the authentic Palestinian leadership, as suggested by Weizman and me. Begin’s position led Weizman and me to resign.

Despite this frustrating experience, I believe that Israeli professors of Middle Eastern studies can ill afford to leisurely confine themselves to the academic ivory tower. As specialists on Arab history and politics and as Israeli citizens they have responsibility to influence the decision making of the government regarding this most crucial problem of Israeli-Palestinian coexistence.

Moshe Ma’oz

Oxford, England

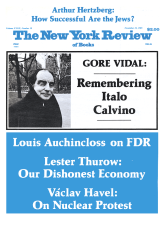

This Issue

November 21, 1985