In Man’s Place in Nature (1863), the first popular attempt to clothe our own species in Darwin’s heresy, Thomas Henry Huxley singled out Edward Tyson’s study of 1699 as “the first account of a manlike ape which has any pretentions to a scientific accuracy and completeness.” In his Anatomy of a Pygmie (actually a chimpanzee), Tyson identified an African ape as intermediate between monkeys and humans, but closer to us than to them. Tyson has become a hero of cardboard history for this supposedly courageous act of permitting the facts of nature to proclaim an unpleasant truth previously suppressed by anthropocentric bias—our continuity with other animals.

In fact, the story should be told precisely the other way around. Tyson continually exaggerated the similarities between chimp and human (by reconstructing the skeleton and musculature of his ape in a fully upright position, for example), while soft-pedaling the differences. Tyson, in fact, did not speak for a heretical and reformist notion of continuity, but for the conventional, culturally embedded idea of a chain of being. This “ladder of life”—just another way of asserting human superiority by awarding the top rung to Homo sapiens—had been challenged by the large gap between monkey and human. Tyson, in other words, did not place his chimp on the rung just below ourselves because he had freed his mind from the cultural habit of interpreting animals in human terms, but for quite the opposite reason—because he longed to affirm a conventional view of human superiority.

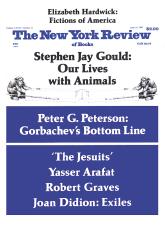

I begin with this tale of history misread in order to make a point underscored in all four books under review: Protagoras was right (but for a reason different from his implied message of human superiority) in proclaiming that man is the measure of all things. It is not that other animals fill less of our pint jug, but that we cannot write, study, or even conceive of other creatures except in overt or implied comparison with ourselves. These books form a fine set of contrasts and similarities because they explore the major and most diverse forms of this ineluctable relationship (leaving out, perhaps, only the contentious issue of organisms used for scientific and medical experimentation). These include the obvious interactions of animals brought into human society—the paradoxical link of husbandry and pet-keeping (Serpell), and the partnership of training (Hearne).

They also illustrate why the two major modes of interaction with animals in nature cannot supply a perspective divorced from profound human entanglement—scientific study, with its claim to objectivity (Goodall), and aesthetic appreciation, with its credo of noninvolvement (Muir). Even the “purest” of all possible positions—that we should grant animals in nature their equal right of place, and simply and absolutely leave them alone in both deed and word—cannot possibly be realized, if only because our alterations of global environment leave almost nothing untouched (our deep-sea machines even hover over vent faunas of the ocean bottom), not to mention the more subtle and unavoidable point that such an argument of “live and let live” contains its own set of rich assumptions about the evolutionary status of humans and other animals.

In the light of this unavoidable entanglement, we can do no more than struggle to define a “proper” relationship with other animals (or, to steer more toward minimalism and less toward moralism, an “appropriate” relationship). Serpell approaches this issue by defining a paradox or apparent contradiction between the two cardinal uses of animals in human society—eating and petting. Serpell does not regard flesh-eating by humans as cruel per se, but he does graphically describe the contrast between older styles of family farm or free-range grazing (where animals suffered not at all, or perhaps only at the last moments of transport and slaughter) and the modern economy of “intensive” or “zerorange” husbandry, where animals are confined all their lives in interior stalls that hardly provide room for lying down. With food supplied at one end, and waste removed from the other, they become simple “throughput” machines for the production of beef or bacon.

How, Serpell asks, can we tolerate such cruelty in a society that lavishly displays its affection for animals in the extraordinary attention and expense that so many of us invest in pet-keeping? In part, of course, most Americans simply do not know (or prefer to look the other way when told) about the sorry lives of their evening meals. But Serpell argues that the paradox cannot be resolved by simple ignorance about one of its opposing terms. He claims instead that we resolve the contradiction by denigrating pet-keeping as the silly and peculiar habit of odd and lonely people who need either a child substitute or some other surrogate for the proper human relationships that their personal problems or psychic makeup preclude.

Advertisement

In the Company of Animals therefore becomes, primarily, a defense of the pervasiveness and appropriateness of pet-keeping in human society. Arguing by copious example in a thoroughly researched and well-written book, Serpell demonstrates that pet-keeping appeals both to a wide variety of cultures throughout the world, and to all social classes within Western society. It is not an indulgence of the rich, idle, and pampered, but a need (or at least a strong desire) felt by many who must shoulder quite a burden of expense, time, and responsibility in order to maintain their companions. Something deep and meaningful must flow from animal to human. Citing the medical and psychological benefits of pet-keeping, Serpell concludes:

Far from being perverted, extravagant, or the victims of misplaced parental instincts, the majority of pet-owners are normal rational people who make use of animals to augment their existing social relationships, and to enhance their own psychological and physical welfare.

I agree entirely with this argument, but must question the frame that Serpell constructs for its presentation. I am not convinced that we try to resolve the paradox between pet-keeping and slaughter by belittling the pet-keepers, thus forging a consistency from our worst practices. How can Serpell claim that “we” denigrate pet-keeping when more than half of us are in the supposedly disparaged category. To say that “we” belittle pet-keeping when most of us keep pets produces a logical conundrum much like the old claim of 1920s eugenics that the average mental age of Americans is thirteen. (Since there can be no standard apart from the general population, and therefore nowhere to measure thirteen as an external criterion, where can a “we” be found outside the majority of pet owners who, I assume, like and defend what they are doing.)

Serpell’s paradox therefore presses even more strongly upon us, for society does not even propose a standard resolution for him to challenge. But can this paradox be defined as something special about our relationship with animals? I don’t think so. The inconsistency between slaughter and pet-keeping is but one case among the dissonances that we all accept to make life supportable in a crazy world, to create islands of sense and comfort in a sea of danger. How else can we tolerate any of life’s real and immediate pleasures in a world of apartheid, AIDS, and threat of nuclear annihilation. Be thankful for this guide of sanity, but beware of the complacency that flows too easily from its comfort.

If Serpell treats the major modes of exploitation—what animals can do for us, either as food or companionship—Vicki Hearne explores the deepest form of explicit partnership: the exacting discipline of animal training. Her title, Adam’s Task, invokes the responsibilities imparted by the second, and less familiar, biblical tale of creation (Genesis 2), where God makes Adam first, then creates other animals, brings them to his first man, and gives Adam the task of naming each species. We usually view this story as more chauvinistic and anthropocentric than the traditional version of Genesis I, where humans are merely the final term in a continuous sequence of creation lasting for six days. But Hearne, who teaches English and ponders philosophy while maintaining a career in training dogs and horses, argues that Genesis 2 is the better story for forging mutual respect—for training engenders the responsibility of partnership, while the differing natures of human trainer and animal partner preclude any concept of domination or exploitation.

She asks if the trainer’s art is “just a sentimentalization of the enslavement of the domestic animal,” and replies:

Well, dog trainers and horse trainers insist that training…results in ennoblement, in the development of the animal’s character and in the development of both the animal’s and the handler’s sense of responsibility and honesty.

Hearne presents this humane and wise resolution for how animals, forced to live in our society and on our terms, can win respect and approbation for their nature (and thus, in a deep sense, their freedom) from within. Yet she mars this message with a withering scorn for any other view, thus herding her animals and their trainers into a citadel, besieged by the fainthearted softies of misplaced sugary kindness. Her self-styled enemies are both academic liberals (ignorant and hypocritical) and Serpell’s pet-keepers (soft and self-centered).

The academics, in her view, particularly those who study animals in psychological laboratories, display the special ignorance of false objectivity. They eschew the ordinary anthropomorphic language that imputes emotions and intentions to animals, and insist instead upon a supposedly “neutral” description hiding an unstated theory that regards animals as Cartesian machines.

But their hypocrisy is even worse. These academics preach a holier-than-thou version of kindness among human beings. Misunderstanding the art and mutuality of training, they brand it coercion and, constantly seeking metaphors and synecdoches to affirm their own moral superiority, accuse trainers of a species of Nazism. Hearne writes that “one must get past the notion of the bridle as an instrument of the kind of subjection that, in my experience, exists only in the fantasy lives of people who have bizarre notions about the nature of power.” Trainers, for Hearne, are martyrs on the scapegoat principle:

Advertisement

There has to be a separate class to get bitten, kicked and stomped on so that the humane and schizoid patter can continue without interruption. Like policemen, trainers exist on the frontiers of social order, as a kind of windbreak.

For the softhearted and weak-willed animal lover, “the humaniac” of her scorn, Hearne has even more contempt. The academic, at least, is ignorant, but the pampering pet-keeper destroys the souls of animals in the name of love and kindness. Consider her tale of a man who has not properly trained his Great Dane:

He is working about as hard as anyone can at not correcting his dog. The sight of him inspires instinctive revulsion in me, as does the sight of anyone who encourages a dog to misbehave, especially if they, while doing so, look around smiling genially to see if anyone is admiring the display of “love.”

Her distaste extends even to the dogs favored by those who reject the noble fighting breeds: “In a true fighting dog there is no ill temper, nothing personal held against an opponent, no petty resentments of the sort found in the snappy, ignoble animals so beloved of people who want to kill Pit Bulls.”

Against these deprecations, I can only offer a personal testimony of one quite ordinary outsider. I suppose that my credentials as an academic liberal are as good as anyone else’s, impeccable I would even maintain. But I just don’t recognize myself in Hearne’s caricatures—and I think they become (like Serpell’s on those who belittle pets) convenient and misleading fictions for hinging an argument. Perhaps we evolutionary biologists who work on whole organisms in nature are different from experimentalists in laboratories, but my fraternity does not shun anthropomorphic language, particularly for mammals with close genealogical ties to people. How else can we treat creatures with the same body parts, and some of the same emotional expressions, as ourselves? The point is even clearer for domesticated animals, selected in some cases for particular human ends over thousands of years. After all, we have tried to breed specific traits with human names into them.

To be sure, animals are not pliant vessels; they will represent our attempts in diverse ways. But still, if we breed a frankfurter-shaped dog with a propensity for digging into badger holes, and the dog then digs into badger holes, what can we say except that the dog is hunting badgers, and even likes to do so. Still, the license for anthropomorphism does include some restrictions about fairness and prejudice. Hearne may glower and rant at the “humaniacs” as much as she pleases (for mouthing off is a human right, however unseemly), but why must she brand their dogs as “scrappy and ignoble” just because she doesn’t like the owners?

On the subject of liberal hypocrisy, we do not all view animal training as an extension of fascism. I, for one, have always had an admiration approaching awe for the great achievements in dressage and circus animal acts. As a child, I particularly loved the circus spectacle of nearly twenty elephants arranged in a long line, each on its hind legs with front limbs perched on the back of another—the whole array looking like a row of dominoes in the process of falling down. I always thought that the lion tamer’s whip guided the animals, and did not cut flesh. I simply assumed that animals would not do these wonderful and complex things out of terror and breakage of soul, and that good trainers must evoke these behaviors by forging a partnership. I have long been disturbed that academics do not go to the real professionals when they need judgments in matters outside their competence. The acts of self-proclaimed psychics must be judged by magicians; the claims that chimps can be taught to speak by signing must be evaluated by animal trainers.

Thus I applaud Hearne’s basic argument that good training is a high art that can bring forth the nobility of an animal’s nature while demanding as much from the human partner in return. After all, the Latin root of discipline means rigor and education—a leading forth. But I strongly reject the two major consequences of this argument. First, while we may not gainsay Hearne’s personal choice of training as the highest mode of interaction between human and animal in society, we must reject her charge that the nobility of training condemns other popular styles because they contradict an animal’s nature. Still upset about the Great Dane cited previously, she writes a few pages later:

Try to understand this. Look in your imagination at the noble head of a Great Dane…and understand what is being wasted. The dog, like any creature possessed of a soul, is immortal, until he dies, that is. And what is being wasted is his immortality, and infinity, too, because mishandling a dog is that sort of offense.

But, to bring up the second consequence, how does Hearne know the nature of an animal’s soul; and, more important, how does she know that others with different ideas don’t know? Has the oracle of three-headed Cerberus told her? I can accept metaphors about the nobility of intrinsic nature, but when Hearne tries to draw distant consequences that grant the metaphor an essential biological truth, then, horseman that I am, I can only shout “whoa.” The argument that nobility lies in the recognition of a creature’s true or innate being, and the subsequent guiding of its life in conformity with this supposed nature, has an ancient political lineage. It is, indeed, the standard argument that intellectuals have always supplied for state power: oppression is not truly oppression, but rather confers a proper status that permits the subjugated to realize their essential natures. Thus feudalism was justified as a partnership between serf and lord, with clear rights and responsibilities on each side, and a shaping of roles according to the different natures of the contracting parties. Still, whatever the real responsibilities of lords, one may be excused for detecting a whiff of asymmetry in the bargain, and for wondering whether anyone ever asked the serfs for their assent.

Now, I can imagine Hearne’s response: “There you (knee-jerk academic liberal) go again.” She might argue that she never meant to generalize the argument beyond the bond of humans with other animals. After all, other species do have natures radically different from ours, while human equality negates the argument that oppression of some groups only permits them the nobility of realizing their true and different beings. (Who knows, perhaps an honorable feudalism would have been an acceptable arrangement if one of our australopithecine forebears had survived as a half-intelligent species alongside us.) But this defense will not wash, for Hearne continually pushes her argument to a generality well beyond the relationship of human and animal. She ends an interesting essay on commands, for example, with an explicit extension to authority in human relationships (I don’t disagree, by the way, but merely portray her willingness to generalize from our pacts of training with animals):

In cheerfully suggesting that authority is essential in our relationships, logically essential to speaking, that talking depends on the possibility of command, I haven’t forgotten the taint in our authority…. We can follow, understand, only things and people we can command, and we can command only whom and what we can follow.

And her basic definition of so central a concept as “kindness” is explicitly rooted (incorrectly this time, I think) in the central term of her philosophy of training: evoking the true essence of a creature different from ourselves:

To be kind to a creature may be to be what we call harsh (though not cruel), but it is always to respect the kind of being the creature is, and the deepest kindness is the natural kind, when your being is matched to the creature’s, perhaps by a kindly inclining.

My distress and disagreement finally congealed in one key passage, perhaps an afterthought to Hearne, but to me a key to the deep error of her generalizations, both philosophically and politically. She writes an interesting chapter defending Pit Bulls, both her own partner in training and breeds in general; she argues that their much ballyhooed transgressions are a consequence of poor training, not their diabolical nature. She then, in conclusion, muses on the ethical rightness of “rolling” Pit Bulls (allowing them to fight) provided that equal dogs are matched in properly regulated contests. We must understand, she reminds us, that “the fights are, unless one dog quits, fights to the death”—so no philosophical softness, or namby-pamby, here. Although she would not place Belle, her own dog, into such a fight, she does defend the possibility:

With certain dogs, not only is it not cruel to “roll” them (give them real fighting, as opposed to mere scrapping, experience), it is cruel to prevent them from fighting, in the way it is cruel to put birds in cages, or at least in cages that are too small for them.

And why can death in the pain of battle be so defended? Because it matches the essential nature of these particular Pit Bulls:

So it is possible for me to contemplate the possibility that allowing the right Pit Bulls, in the hands of the right people, to fight can be called kind because it answers to some energy essential to the creature, and I think of energy, when I think of certain horses, as the need for heroism.

How can anyone defend such misplaced Platonism more than a hundred years after Darwin? How can we speak of an essence so deep, so pure, so inexorable, so special, so immutably part of the creature’s definition that we must follow it whatever the consequences—even to death in agony? How can we defend such a general idea in a world of change and variety, where we can only define a species by its range of momentary variability, not by any permanent essential nature? And how can we dare to suggest, in this particular case, that a drive to fight to the death defines a Ding-an-sich, before which we can only bow in ultimate respect—when it is we humans who have bred this trait into Pit Bulls for our own cruel delectation? Essential nature, fiddlesticks. At this point, I will cheerfully take all the sugary squishiness of Serpell’s pet owner to the adamantine toughness of a trainer who can confuse a transitory trait constructed by humans with a definition of soul, and therefore contemplate an animal’s death in pain for the virtue (so manly in its etymology) of philosophical consistency.

Since supposed opposites often curve around to meet each other, Hearne’s notion of partnership in training has its counterpart in John Muir’s idea of ultimate regard by letting animals live their own lives in nature. In this view, true respect lies either in the greatest mutuality of explicit interaction or in strict noninterference; all else is exploitation.

In Muir Among the Animals, the Sierra Club has commemorated its founder—John Muir died in 1914—by bringing together his sparse writings about animals (he had more to say about mountain scenery). If we could view animals in other than human terms, Muir might be our best candidate—and his failure, despite his stated attempt, indicates the impossibility of such a conceit. Muir would simply have us leave them alone (our resulting enjoyment of their beauty would then be a happy side-consequence, not the reason for this moral stance). More than other nature writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Muir attempts the kind of “objectivity” that claims to take all creatures as they come. He cautions us explicitly about anthropocentrism and (unlike many contemporaries) admires fierce predators and noisome insects as much as the pretty and colorful things that form the staple of his saccharine, adjective-laden genre—traditional nature writing.

Muir’s essays may be read in many guises. In preparing this article, I couldn’t help concentrating upon his inability to express the fascination of animals, or even to state the basis for his philosophy of our noninvolvement in their affairs, in any other than human terms. Even his two major arguments against anthropocentrism rely upon dubious views of nature that arise from human hopes about the world’s benevolence and intelligibility: first, that “Nature’s object in making animals and plants might possibly be first of all the happiness of each one of them, not the creation of all for the happiness of one”; and, second, that a harmonious world requires all its inhabitants:

The universe would be incomplete without man; but it would also be incomplete without the smallest transmicroscopic creature that dwells beyond our conceitful eyes and knowledge.

But our intrusion extends well beyond these embodiments of our hopes in a general philosophy of nature. Every animal story offers some moral instruction. “Any glimpse into the life of an animal,” Muir writes, “quickens our own and makes it so much the larger and better in every way.” Mountain sheep teach us “the boundless sufficiency of wild nature displayed in their invention, construction, and keeping.” Even beds of fossils testify to the joys of nature without human interference (and thereby show human imposition in the very concept of such primeval bliss): “It is a great comfort to learn that vast multitudes of creatures, great and small and infinite in number, lived and had a good time in God’s love before man was created.”

Human terms and values pervade Muir’s descriptions as well. Nonmigratory birds are praised for independence because they can stay put and need not move to follow their preferred resources: “They are forever independent in the matter of food supply, which gives so many of us trouble, dragging us here and there away from our best work.” The water ouzel “has the oddest, neatest manners imaginable, and all his gestures as he flits about in the wild, dashing waters bespeak the utmost cheerfulness and confidence.” Even grasshoppers partake of nature’s fun: “The life of this comic redlegs, the mountain’s merriest child, seems to be made up of pure, condensed gayety.” From Hearne’s toughness in partnership to Muir’s merriment in independence, animals seem unable to escape their characterization for our purposes.

A traditional scientist might argue that if better understanding requires a radical departure from these human impositions of manners, bridles, and morals, then noninterfering study of natural populations should receive our highest priority. For no species could such a goal be more important or more difficult than for chimpanzees.

We have known for a long time that the African apes (chimps and gorillas) are our closest genealogical relatives among primates. Only recently has biochemical data been converging upon a surprising conclusion within this general knowledge: of the three species (chimp, gorilla, and human) the closest relatives by recency of common ancestry are not chimp and gorilla, as always assumed, but chimp and human. Thus the striking features held in common by chimp and gorilla, knuckle-walking in particular, are not unique specializations derived after the split from humans, but retained ancestral traits that must also have been present in the common forebear of chimps and humans.

The best estimate (based on genetic similarities) for the chimp-human split is only six to eight million years ago. Chimps, in other words, are evolutionarily much closer to us than we had ever dared to imagine (and Mr. Tyson, of my introduction, was right for the wrong reason after all). Therefore, accepting the evolutionist’s basic premise that genealogical closeness is the key to similarity of the most meaningful kind in biology, chimps vastly surpass all other species in their promise as sources of insight, based on methods of comparative zoology, about ourselves and our history. Since chimps are confined to dwindling areas of native vegetation in Africa, it goes without saying that we had better move fast (and with extensive resources) if we wish to benefit from this source of knowledge in its natural environment. If we blow this one too, we will never get another chance. And there can be only one closest species.

In this light, I believe that Jane Goodall is one of the intellectual heroes of this century. More than twenty-five years ago, when she was in her twenties, by sheer gumption, and virtually alone, she began her studies of a chimpanzee community at Gombe, in Tanzania. She has persisted ever since, and continues still, by struggle and courage—and she has amassed in this quarter century our first adequate and comprehensive account of the natural behavior of our closest animal relative. What in all natural history could possibly be of more interest and importance to us? This large and well-illustrated book (never forget that all primates are primarily visual animals) is a long progress report of work that must continue.

Natural historians insist that their work can only proceed beyond the anecdotal by continuous, repeated close observation—for there are no essences, there is no such thing as “the chimpanzee.” You can’t bring a few into a laboratory, make some measurements, calculate an average, and find out, thereby, what chimpness is. There are no shortcuts. Individuality does more than matter; it is of the essence. You must learn to recognize individual chimps and follow them for years, recording their peculiarities, their differences, and their interactions. It may seem quaint to some people who fail to grasp the power of natural history that this great work of science largely tells stories about individual creatures with funny names like Jomeo, Passion, and David Greybeard. When you understand why nature’s complexity can only be unraveled this way, why individuality matters so crucially, then you are in a position to understand what the sciences of history are all about. I treasure this book most of all for its quiet and unobtrusive proof, by iterated example rather than theoretical bombast, that close observation of individual differences can be as powerful a method in science as the quantification of predictable behavior in a zillion identical atoms (we need both styles in their proper slots of our multifarious world).

Close, long-continued, and maximally noninterfering observation has paid its greatest dividend in thoroughly revising the clinical or romantic views of chimpanzees that prevailed previously. Against the clinical view, Goodall has taught us how the primary features of chimp society at any time are not direct consequences of first principles or measures of simple quantities (size, number of aggressive encounters), but irreducible and unique features of individual personalities and their complex interactions. The position of the dominant, or alpha, male, for example, has not generally been held by the biggest or strongest at Gombe, but by chimps who work hard at bettering their social positions and who combine inventiveness with careful and calculating attention to social interactions. (Mike, for example, bluffed his way from low rank in 1963 to alpha in 1964 by learning to hit empty kerosene cans together while charging his superiors. Goblin, the current incumbent, is decidedly below average in size, but a master of social manipulation in forging and breaking alliances at propitious times.)

Against the romantic view of chimps as peaceful inhabitants of the abundant, primeval forest, Goodall’s attention to detail has reformulated our view toward something closer to Hobbes’s epithet for the lives of their closest relatives—nasty, brutish, and short. Not that chimps are brutal killers or nasty schemers; rather, they show such a wide range of behaviors in such flexible situations, from an abundance of enormous affection and kindness, to cannibalism of infants and murder with intent to kill. As in human society, the effects of occasional brutality outweigh a thousand acts of unrecorded kindness in setting the basic events of social history. Of sixty-six recorded deaths, more than half resulted from disease, but 20 percent occurred as the result of injury in fights or falls.

Continued close observation has also affirmed another important principle of historicity and individuality. The current state of a chimpanzee society cannot be assessed by accumulating the ordinary, predictable events of daily life (if so, the experimentalist’s procedure of occasional random sampling might suffice). Major features are consequences of rare largescale events (the analogues of war, famine, and pestilence in our lives)—true historical particulars that can only be appreciated by watching, not predicted from theory. Goodall teaches us, for example, how much about group size, composition, and dynamics of the Gombe chimpanzees can be explained by three particular events: a polio outbreak (probably transmitted from humans) in 1966 leading to six deaths and six cripplings; the split of her community into two groups during 1970-1972, and the later annihilation of one by males of the other; and the killing and cannibalism of up to ten infants by one female (named, of all things, Passion) and her adult daughter, following their “discovery” of this food source in 1974. They ganged up on other females and seized their babies, leading to the death of all but one infant in the Gombe community during the four-year period of their depredations.

The study of chimps places us in a double bind with respect to our need for reliable knowledge about their social lives: our affection, arising from an acute perception of biological affinity, draws us inexorably to these animals, yet our need for distancing to break the bonds of bias and expectation has never been greater. We cannot, as this review holds, see animals in any other than human terms; yet, in some immediate sense, we must struggle for maximal distance.

This struggle, waged consciously, courageously, and above all humanely, by Goodall, is an underlying and coordinating theme of this volume. She admits and defends her proper involvement (for objectivity is not an erasure of emotions, but a firm recognition of their inevitable role and presence). She writes: “I readily admit to a high level of emotional involvement with individual chimpanzees—without which, I suspect, the research would have come to an end many years ago.” She loved David Greybeard, the wise old male who comforted her and taught her so much during her greenhorn years—as she hated the cannibal Passion who nearly extinguished an entire generation. (Can we even begin to appreciate the power of her temptation to intervene, and the absolute need, so respected by Goodall, to let events run their course, while recording the consumption of infants in all possible observational detail?)

Goodall began by cultivating a closeness that she had to break when she realized that such relationships were not only distorting the behavior of individual chimpanzees, but also threatening to alter the character of entire communities. I felt her emotional pain and appreciated what she has done all the more (for science can be one hell of a harsh taskmaster) in reading:

In the early years of the research I actively encouraged social contact—play or grooming—with six different chimpanzees. For me personally, these contacts were a major break-through; they meant that I had won the trust of creatures who initially had fled when they saw me in the distance. However, once it became evident that the research would continue into the future, it was necessary to discourage contacts of this sort.

(Goodall had, perhaps significantly, altered the history and community structure of Gombe chimpanzees during the early years of her research by feeding bananas essentially ad libitum to chimps who visited her camp. One can well imagine the impact of introducing such a consistent and abundant resource in a world marked by unpredictability and seasonality of foodstuffs. This magnet brought many chimps into camp, and into levels of social contact that would probably not have been achieved otherwise. Goodall recognized the problem and has, ever since, greatly restricted the number and timing of bananas supplied in camp. But the introduction of this resource, and its later restriction, may have been a major influence in first establishing an enlarged community and then precipitating the split that led to the eventual annihilation of one subgroup by the other.)

I do not recount this episode to criticize. Goodall’s decisions were correct, and all of us who pursue science under difficult conditions in the bush know that purist research designs are pipe dreams, and that pragmatism must often rule. (You can’t just march off into dense foliage and find chimps; you must first make contact and build trust in order to win acceptance and establish the possibility of following in the wild.) I mention this crucial incident only to point out once again how subtle and complex our necessary interaction with such a flexible and intelligent creature must be.

Yet the most instructive examples lie not in overt incidents, but in more general uses of language, or the way questions were posed. As an obvious case, Goodall did not recognize for many years how much females participate in hunts for meat (though males are more active) because “until 1976 females were only rarely the subject of full-day or consecutive-day follows: the new information on hunting has largely been acquired by rectifying that bias.”

Speaking of conventionalities imposed by human perceptions, I was shaken by occasional statements in the worst tradition of the chain of being. “It is evident that chimpanzees have made considerable progress along the road to humanlike love and compassion.” Or, comparing her chimps with their more sociable cousin, Pan paniscus, the pygmy chimp: “It sounds like a utopian society—and viewed against this, it would seem that the Gombe chimpanzees have a long way to go.” But the Gombe chimps are not on any road, and the metaphor can only produce a biased itinerary.

More subtly, I found again and again that both the scheme of research and the design of this volume follow our perception of interest, and I wondered over and over, page after page, what we might be missing that is important to chimpanzees. Thus chapters on behaviors similar to actions that either trouble us when expressed by humans, or are conventionally judged crucial to the evolution of our own intelligence, are given prominence in length and word (hunting, territoriality, and the analogues of warfare), while calmer and less obtrusive behaviors without clear human analogues (the extraordinary attention given to mutual grooming, in particular) are not as intensely pondered. Thus Goodall presents a long speculation on the role of warfare in precipitating the evolution of intelligence, but offers no similar pride of place to childhood play, or to the complex relationships and mutual interchange of grooming for that matter.

What are we missing by parsing the behavior of chimpanzees into the conventional categories recognized largely from our own behavior? What other taxonomies might revolutionize our view—for taxonomies are theories of order? What are we missing because we must place all we see into slots of our usual taxonomy? Why do chimps eat a walnutshell full of termite clay every day? Must we view such an action as an ecological adaptation (good source of concentrated soil nutrients, Goodall cogently suggests)—or might it represent something that does not lie within any of our categories, so that we miss its meaning entirely or record the wrong thing? What does the prison of our language do to the possibilities of interpretation? What would a taxonomy based on things not done look like? How can we comprehend the soul of a creature whose watchword is flexibility with a language that parcels actions into discrete categories given definite names? And if this be a problem for chimps, how can we hope to understand ourselves?

Animals are, and must be, our mirror. And I know no better reason for a continued struggle to understand them, and a persistent drive to define relationships of respect, than this necessary wedlock. But what are we missing because we have made ourselves, for reasons of blind vanity and hubris, the measure of all things? Gunnar Myrdal, whose recent death we all lament, grappled with this question in his masterpiece on human intolerance:

There must still be…countless errors…that no living man can yet detect, because of the fog within which our type of Western culture envelops us. Cultural influences have set up the assumptions about the mind, the body, and the universe with which we begin; pose the questions we ask; influence the facts we seek; determine the interpretation we give these facts; and direct our reaction to these interpretations and conclusions.

This, we must understand, is not merely “An American Dilemma,” but the central problem of all our natural knowledge.

This Issue

June 25, 1987