1.

On Sunday night, July 31, Israelis throughout the country were watching Jordanian television. King Hussein’s speech was broadcast twice, once in Arabic and again with a voice-over in English. I watched and listened with special interest, for just a few hours before I had crossed the Allenby Bridge to Israel after a three-day visit in Jordan. Immediately after the speech Israeli commentators outdid one another in finding hidden political ploys in the king’s declarations. By the following weekend the analysis had become less clever, and more somber. The most serious newspaper commentators had come to understand that King Hussein had not made just another move in a continuing game of simultaneous chess with Israel, the PLO, the United States, and the many forces in the Arab world.

The king had gone back to the basic lasting issues of the conflict between Israel and the Arabs. The very staging of his speech conveyed that message. Hussein had spoken while sitting behind a simple desk in a bare room, or so it seemed to the eye of the camera, with a large portrait of his grandfather, King Abdullah, on the wall behind him. Forty years earlier, at the end of the war with Israel, Abdullah had made the fateful decision to annex the West Bank. Hussein was now reversing this decision—but clearly, sitting under Abdullah’s portrait, he could not have thought that he was betraying what he had learned from the grandfather whom he revered. To understand this paradox one must recall the events of 1948–1949.

At the end of the war against the nascent state of Israel, all of the invading Arab states signed armistice agreements with Israel, but they continued to regard the Zionist state as a usurpation of Arab land and to announce that they were waiting for the moment when they would join with the aggrieved Palestinians to reverse al-nakba, “the disaster.” In September 1948, when the war was already lost, the Arab Higher Committee, which was then based in Gaza and was supported by the Egyptians, created the Government of All Palestine. As its name proclaimed, this body was waiting to rule a land regained from the momentarily victorious Jews.

Those months were indeed a great disaster for the Palestinians. At least 600,000, perhaps up to 760,000, fled their homes inside the border that Israel was to establish through war, and only slightly more than 100,000 people remained. Whether the Palestinians fled of their own accord or whether they were expelled by the Israelis has been argued about ever since. Most Israelis prefer to believe that the Arabs left to join the armies and the guerrilla bands that were fighting the Jews, presuming that they would soon return in triumph; the Palestinians insist that very few left of their own will, and that most were either expelled directly or frightened by the massacre of civilians on April 9, 1948, at Deir-Yassin, a village on the western outskirts of Jerusalem, by a joint attacking body of the Irgun and the Stern gang. There some 250 Arabs, most of them noncombatants, were murdered.

These events have recently been studied on the basis of extensive new materials in Israeli archives and in England and America by Benny Morris, the diplomatic correspondent of the Jerusalem Post, in The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem. His conclusions are that during the first months of 1948 middle- and upper-class Palestinians left of their own will in order to avoid the war. But in April and May of 1948 the fear of atrocities “played a major role in certain areas of the country in encouraging flight.” There was never a policy decision by the highest leaders to expel the Arabs, but Israeli military commanders were given authority as early as March “to completely clear vital areas.” This, according to Morris, “allowed the expulsion of hostile or potentially hostile Arab villagers.” He concludes that “it was understood by all concerned,” without any formal discussions of the kind that leave documents behind, that it was best militarily to leave as few Arabs “behind and along the front lines,” and that it would be best politically to have as few Arabs in the Jewish state as possible. This was the thinking of some of the commanders in the field, including even those who had grown up in Mapam political circles, and who were ideologically committed to coexistence with the Arabs.

The question of return of these refugees was on the minds of the Israeli leaders even as the exodus was taking place. After the first truce in the fighting in June 1948 the Arab states were already pressing Israei to let the refugees return to their homes, and the United Nations mediator for Palestine, Court Folke Bernadotte, advocated their cause. The Israeli cabinet decided on June 16 that there could be no return during the war and that the matter would be reconsidered later. As the war resumed, more Arabs ran away, and more and more of them were forced out by direct expulsion. Jews quickly took over abandoned houses and property, even though the Arab population in some places, such as Nazareth, was left entirely untouched. By the time of the armistice agreements with all of the Arab states in the spring and summer of 1949, Israel was neither in the mood nor in the position to allow the return of any substantial number of Palestinians. It was sitting on their property as the spoils of war and it was threatened by their enmity. It needed the space for the hundreds of thousands of new immigrants to Israel. From their refugee camps the Palestinians watched the rapid beginnings of the obliteration of their roots in the land. Inevitably they felt vengeful and unforgiving toward the Israelis, and angry at the Arab states and at their own leaders, all of whom had failed them.1

Advertisement

Abdullah, for his part, acted in his own interest. In December 1948, he created a Palestinian committee in Jericho. This group asked for the union of Palestine and Transjordan, and soon extended Jordanian rule to the West Bank. In February 1950 he formally annexed the region. The Government of All Palestine became irrelevant, and soon ceased to exist. From the moment of annexation the inhabitants of the West Bank were treated as Jordanians. Abdullah decided that the Palestinians who had fled to Jordan, including those in the refugee camps, should be given Jordanian citizenship. Thus Abdullah very swiftly made Jordan into the successor state of the Palestinian state that never was. He was widely, and correctly, suspected of talking with the Israelis about a formal peace treaty, and he was punished by Palestinian nationalists, who murdered him in 1951 in front of Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, before the eyes of his teen-age grandson, Hussein.

During his rule, and especially during his last three years as he reacted to the rise of Israel, Abdullah defined the Jordanian political tradition. He had been made ruler of Jordan (then Transjordan) in 1921 with the help of the British. He was an outsider, for the roots of his family were in the Arabian peninsula, from which they would shortly be expelled by Ibn Saud. His support came not from Arab or Palestinian nationalists, but from Great Britain, which subsidized his government and trained his army.

Abdullah was inevitably fashioned by necessity, if not by conviction, into a pragmatic statesman who dealt not in rhetoric or ideology but rather in compromise and self-interest. To be sure, he was a religious believer who went on foot every day to the mosque to pray. To have gained control of the Old City of Jerusalem, the third holiest place of Islam (after his family had so recently lost Mecca and Medina), meant much to him, but he had no problem in 1948 dividing power in the region with the Jews. Abdullah, like the Israelis, felt threatened by Palestinian nationalism, and, like them, he wished to weaken its force. As a Muslim, he believed, of course, that the faith that had been announced by his ancestor the Prophet would ultimately spread to the whole world, but he was willing to wait for that end of days.

Sitting under his grandfather’s portrait on Sunday night, July 31, Hussein continued his grandfather’s pragmatic politics. Abdullah had thought that he could best rule in Jordan by making it the successor state of the Palestine that never was after the Palestinians had rejected partition. Under changed circumstances Hussein was now announcing in the firmest tones: “Jordan is not Palestine.” After eight months of unrest in the West Bank, with even some threat that the intifada might be taken up by the Palestinians inside Jordan itself, the king had decided that he could not govern the West Bank. After twenty-one years of Israeli occupation the majority of its population, including most of the very stone-throwers who are giving Israel so much trouble, had learned their politics not from Jordan, which would have suppressed the uprising at once, but from Israel’s raucous democratic tradition, and from the often violent factional fights in the PLO.

Indeed, there was a rumor in Amman in the last days of July that a high-ranking delegation of Jordanian officials had recently toured the West Bank, with Israel’s knowledge, and that they had concluded that there was almost no local support for the return of the Jordanians. Abdullah had always believed that rational decisions should be made in the self-interest of the Hashemite ruling family. Hussein was following this example when he reversed his grandfather’s action and de-annexed the West Bank.

Hussein was confronting the Palestinians on both sides of the river. To the Palestinians in his territory, some 60 percent of the population (even though the official Jordanian figure is 40 percent), he was saying that he would not countenance Palestinian nationalism within his country. While I was in Amman it was being said that Jordan was safe only for loyal Jordanians, and that the many ties of people of Palestinian origin with their families on the West Bank were not a reason for Jordan to be used as the staging area for Palestinian nationalism. Hussein was saying to Palestinians everywhere, and especially to those on the West Bank, that they would now have to fight their battle with Israel on their own. Some of the Palestinian nationalists who had for years expressed hatred for Hussein now complained bitterly. Hussein had served their cause by representing the possibility of rational compromise with the Israelis. The ultra-nationalist Palestinians could continue to demand the extinction of Israel, while Hussein’s position shielded them from the embarrassment of being negotiating partners in any discussions with the Israelis, or even with either of the superpowers.

Advertisement

Hussein’s decision upset the Israelis even more than the Palestinians. Since the beginning of their state the Israelis have been using the “Jordanian option,” in one or another form, as a way of avoiding the issue of the Palestinians. The deal that David Ben-Gurion made with Abdullah in 1948 for a partition of Palestine had included, at least on the Israeli side, the presumption that the Palestinians who fled during the 1948 war would somehow disappear into the Arab world, that they would not become part of an increasingly aggressive national irredentist movement. Like Abdullah, the founders of the State of Israel, or most of them, were pragmatic statesmen—and they preferred him to other Arabs. This preference was not a creation of geography, although it is true that Israel’s longest border by far is with Jordan. The issue goes far deeper, to the very nature of politics and war between Jews and Arabs.

The decision by the United Nations, on November 29, 1947, to partition Palestine between a Jewish and an Arab state had been a rational political act. It is true that after the partition vote by the United Nations on November 29, Menachem Begin, as head of the Irgun, issued an order denouncing partition as illegal, and he called for continuing armed struggle to regain the whole of the land. David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann had been saying for years that the historic Land of Israel of Zionist dreams should extend at least to the Jordan River, but they had accepted partition as the best deal that they could get. They were willing to regard the rhetoric about restoring ancient national glory as a far-off dream of no political relevance.

Begin was different; he has never wavered in his belief that the task of Zionism is to achieve the undivided Land of Israel, and that all other Zionist purposes, including even peace, are subordinate to the territorial ideal. But between 1947 and 1949 Begin’s position seemed of no more consequence, despite the separately conducted military actions of the Irgun leaders, than that of the Arab Government of All Palestine. A decision had been made by Israel’s leaders to pursue a rational, this-worldly politics. That meant that before 1967 only small groups of ideological extremists made an issue over the soil of their ancestors being in Jordanian hands. There were sorrow and anger about Jews being barred from the Old City of Jerusalem, but no one of any consequence spoke of a national duty to go to war to reclaim it.

Israel announced that it had no quarrel with any of the Arab states in the region, and that it stood ready to make peace with them. They all refused, partly because the Palestinians were insisting that the Jewish state was illegitimate and that their purpose was to remove it. At various points the Israelis offered privately, and even sometimes publicly, generous deals with which to compensate Palestinian refugees, if only they would give up their claims to the land and settle elsewhere, with the consent of Arab host countries. These offers were always rejected, for any deal with Israel would suggest at least de facto acceptance of the existence of the Jewish state.

The various surveys that were made through the years of Palestinian refugees, whether by private agencies, the Palestinians themselves, or by United Nations officials, showed that most Palestinians, if offered a choice between compensation and return to Israel, would accept compensation and that only a minority would actually choose to return and live inside Israel. But this did not encourage the Israelis to offer such a choice. They were undoubtedly afraid of a fifth column; more fundamentally, they could not grant legitimacy to the Palestinians’ claim that Israel’s land remained their ancestral national home.

Through the years, Israel looked for other Arab partners who would deliver Israel from the Palestinians. As I wrote in these pages at the time,2 Begin found such a partner in Sadat at Camp David in 1979: he gave back all of the Sinai to Egypt in return for Sadat’s standing aside, in reality (as distinct from rhetorically), from the cause of the Palestinians. Like Abdullah before him, Sadat was assassinated by intransigent fundamentalists, at least in part as punishment for the sin of making peace with Israel. It is fashionable nowadays, so fashionable that it has become a supposedly incontrovertible truth, to speak of Israel’s formal peace treaty with Egypt as a historic breakthrough, a turning point, because it was the first formal treaty, with open borders, to be signed with an Arab power. I think that the judgment of the future will be different. The formal peace with Egypt has been followed by very little day-to-day contact between the two countries—far less than Israel has with Jordan—and there is very little trade between Egypt and Israel. The bridges between Israel and Jordan still remain open, even after the king’s speech, and not simply as a convenience for families with relatives on both sides of the river. I was told flatly in Amman by a high-ranking government official that the bridges would remain open as part of Jordan’s permanent policy toward Israel.

In the peace treaty of 1979 with Egypt Israel was really continuing the de facto peace that had been made with Jordan thirty earlier. This was a more open and elaborate deal than the one with Abdullah a generation before, but with Egypt, too, territory was exchanged for peace, and it was seen by Israel as a way to be freed from the pressure of Palestinian nationalism. It was said that Egypt, by signing a formal peace treaty, was the first Arab state to confer legitimacy on Israel. But however suspicious or fearful the Arab nations may be of the Palestinians, they insist that legitimacy can be conferred on Israel only by the Palestinians. What is new today, after forty years and many attempts at avoidance, is that this simple truth can no longer be ignored.

2.

In Israel the Likud, and not the Labor party, is the real loser as the result of Hussein’s announcement. The Likud has been able to pursue its policy of de facto annexation of the West Bank so long as there was substantial Jordanian participation in the region. Jordan provided citizenship and many services for the more than one million Arabs in Judea and Samaria. The extreme and often irrational nationalism of the Jewish settlers, and of their supporters in the hard-line parties, could grow unhindered so long as Jordan cooperated in keeping the formal status quo on the West Bank. No wonder that even today, after Hussein’s declarations, Prime Minister Shamir has refused to heed the calls of some of his own followers to annex the region and to apply Israeli law. From his perspective, it is best to have the Jordanians on the West Bank to keep the Arab population from coming under Israeli law.

Shamir is more than content that even today, after Hussein’s announcement deannexing the West Bank, Jordan is still providing three vital services: it is issuing passports, maintaining a system of Islamic courts that permits Arabs to avoid the Israeli courts, and stamping the diplomas of high school graduates so that they can be admitted to universities anywhere in the Arab world. This may be enough for the moment to provide the Palestinians on the West Bank with sufficient “autonomy,” through their links with the rest of the Arab world, so they will not feel wholly trapped inside the occupied territories. I have no special knowledge of Jordanian thinking on these matters, but the logic of what they have done so far suggests that they may soon cease providing even this last cover for the partisans of the “undivided Land of Israel.” By removing themselves completely, as they very nearly have already done, the Jordanians will force Israel’s hawks to face the Palestinian question, as the West Bank and Gaza become harder and harder to govern.

Doves in the Labor party were visibly upset, at first, by the king’s speech and the actions that followed from it. Their immediate judgment was that his ending the “Jordanian option,” which was the central plank of their foreign policy, would cost them the election in November, but it has long been an open secret in Israel that many doves in the Labor party, even as they have publicly favored the “Jordanian option,” are willing to redivide the Holy Land with a demilitarized Palestinian state.

This has not been their public rhetoric. In a recent book that went to press before the beginning of the intifada, Abraham Tamir, the director-general of Israel’s foreign office, and as such a principal spokesman for Shimon Peres, insisted that an international conference could take place only if the Arabs were represented by “a Jordanian-Palestinian delegation and not a Jordanian-PLO delegation.” 3 In his book, Major-General Tamir, a senior security official for many years, ruled out annexing the West Bank or returning it to Jordan, or accepting a separate Palestinian state. He continued to prefer a confederation between Israel and a Jordanian-Palestinian federal state. Now after the outbreak of the intifada and Hussein’s speech, Tamir has come closer to accepting the possibility of the independent Palestinian state that he previously ruled out. Speaking in Washington on August 31, 1988, he said that “everyone knows that the PLO is the national representative of the Palestinians: there is no replacement for them. So the question is not how to replace the PLO but to change it.”4

In the context of Israeli politics, this means that a PLO that recognizes Israel and gives up terror and armed rebellion as its instrument of nationalism would be an acceptable negotiating partner. General Tamir is hardly likely to have imagined that his “changed PLO” will abandon the idea of a Palestinian state, because, as he himself says in his book, the PLO insists that “without a right to self-determination” which leads to an “independent Palestinian Arab state” there can be no political solution. Tamir has thus said publicly in Washington what has been said in private for a long time by some moderates in Israel—indeed, some of the very people who have been insisting for public consumption that the PLO could never be considered a negotiating partner. Tamir was immediately attacked by Shamir, who demanded that if Peres did not fire him, it would prove that dealing with the PLO was the foreign policy of Labor.

This exchange sharpened the longstanding disagreement over the occupied territories between Likud and Labor. Earlier this year Peres was willing to attend an international conference, as envisaged by the Shultz plan, in which Jordanians and Palestinians would take part, while the PLO as such would be excluded. But Shamir argued that since such a meeting would lead inevitably to a Palestinian state, and that since Peres knew it, he was not really an opponent of such a state. In 1979, when he was Speaker of the Knesset, Shamir had made the same case when he joined the majority of the Likud party in voting against the Camp David agreements signed by the Likud’s own leader, Menachem Begin. Future negotiations with Palestinians about local autonomy, Shamir said, would lead inevitably to a Palestinian state.

What Shamir is still saying in the present political campaign, even after Hussein’s speech, is that he wants negotiations with the Jordanians, and without any prior conditions. He does not want to talk with the Palestinians about anything at all; if he absolutely must, he will discuss very minor local issues concerning parts of the West Bank. Since Hussein has announced that he has no intention of ever entering such negotiations with Israel, the Likud is essentially using code words to suggest to Israel’s voters that it, unlike Labor, would rather fight the intifada indefinitely than negotiate with the leaders of Palestinian nationalism.

This position seems a sure winner, for all the polls of Israel’s voters so far have shown them to be opposed to dealing with the PLO by a margin of two to one. Many of these voters are in the Labor party, which contains a wide spectrum of opinion, from hawks whose views are nearly as hard-line as Shamir’s to ultra-doves. Shamir’s insistence that Labor is soft on the PLO is thus a way of scaring the hawkish Labor constituency into voting for him. He may succeed. Tamir was indeed saying out loud what Labor’s hard-liners don’t want to hear; and the real political thinking of the Labor doves, and of those to the left of them, such as the Civil Rights party led by Shulamit Aloni, or the Mapam, which has historically believed in some expression of Palestinian-Jewish equality, is that now is the time to negotiate with the PLO, if it has the power to stop the riots and agrees to recognize Israel.

Shamir is right; it is conceivable to Israel’s doves that a PLO declaration that is acceptable to them might be forthcoming. On Monday night, September 6, Shimon Peres opened the election campaign by insisting that Labor would “terminate” Israeli rule over 1.5 million Palestinian Arabs who are inhabitants of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Since Peres knows that Jordan does not want these territories, he means either a policy of unilateral withdrawal or of negotiating the future with Palestinians. In either event, a Palestinian state of some kind may be inevitable. Hussein has forced doves in the Labor party to be more open in accepting the possibility of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza.

But Israel’s right-wing parties are already in difficulty for they must suggest to their followers that they know how to deal with the more and more restless Arabs who now make up 40 percent of the population of Israel and the occupied territories. General Ariel Sharon has stopped talking, at least for the moment, of helping the Palestinians overthrow the Hashemite government in Jordan; he has recently proposed unilateral Israeli withdrawal from the population centers while retaining most of the territory of the West Bank. Two of the younger members of the Likud, Ehud Olmert and Dan Meridor, suggested in private conversations that Israel could continue to hold the West Bank and Gaza by giving the inhabitants “real” regional autonomy, although just what they mean by this remains vague. When these opinions were leaked to the press, both Meridor and Olmert denied that they had said anything definite about autonomy at all.

In any event, such views as these do not seem entirely anathema to the Likud. One third or more of those who are planning to vote for that party in the November elections have said in several polls that they are for detaching the West Bank Arabs from Israeli rule and granting them civil autonomy. At the other extreme, there are many in the Likud, especially among the usual sources of popular opinion, the taxi drivers and proprietors of pushcarts in the street markets, who are waiting for the intifada to become more violent, waiting for the young Palestinians to use “hot arms,” so that it would be no embarrassment to Israel to shoot back and crush the uprising completely.

The most popular new formula is “transfer.” Almost half of Israel’s voters are suddenly indicating assent to a solution most would have found repugnant just a few months ago—pushing out hundreds of thousands of the West Bank and Gaza Arabs. Those who talk of transfer have not yet answered the question of where the transferees would go. Perhaps they think that the Jordanians and Lebanese would not thrust back people driven across their borders. In any case the growing respectability of the idea of transfer reflects another reality—that the jailing of several thousand Palestinians without charges, and the harsh treatment of some of them in detention camps, has substantial support behind it.

These contradictory opinions within the Likud cannot be harmonized into a policy. What everyone on Israel’s right wing now knows, despite Shamir’s clinging in public to the suggestion that the Jordanians will come back into the picture and negotiate with him, is that there are no more surrogates left to help the Likud to avoid acknowledging that a ceaseless and increasingly repressive civil war will be needed to sustain its principle of the undivided Land of Israel. The evidence is that most of Israel’s right wing prefers the situation of Belfast, or even worse disorder, to compromise. The pragmatists in the right-wing camp are under pressure from religious and nationalist extremists who join in making an argument that has a powerful effect in Israel: if the Palestinians have a legitimate right to Judea and Samaria, their claim on Jaffa is just as legitimate—and the whole of the land is what they really want. What used to be most moderate of the religious parties, the formerly centrist Mafdal, now announces in huge advertisements in Israel’s newspapers that it absolutely rules out the return of territory on the West Bank to any foreign power and refuses to allow any Palestinian national entity to exist on any terms west of the Jordan—and yet the Mafdal says that it will “hope for peace and work with all its strength to achieve it.”5

These concluding phrases, if they mean anything at all, can only suggest that the Mafdal hopes that the intifada will be completely suppressed. But the ideologues of the Likud are mostly Ashkenazim. Jews of European and even of American origin, while most of the Likud voters are of North African extraction. Their relationship to the Arabs. among whom their parents’ generation was born and raised, is a mixture of ethnic anger and the sense that the Arabs are a fact of life and one must somehow deal with them. The beginnings of pragmatism even among a few of the leaders of the Likud will find some echo in these circles, when the choice is clearly between permanent Belfast in the Middle East and dividing Jews and Palestinians from each other so each will have his own side of the street.

3.

The PLO is now facing problem as severe as those confronting the Israelis. The Palestinians can no longer blame Jordanian interference for their difficulties in making fundamental political decisions. They are acting much as the Zionists behaved in the mid-1940s, lurching from the factionalism and the high-flown rhetoric characteristic of those who see no hope of achieving power, toward compromise and realism, as befits a possible future government of the West Bank and Gaza. The differing texts of the recent declarations by PLO leaders, including those of Arafat himself as he “plays with the idea” (as he said in Geneva when he met Pérez de Cuéllar) of establishing a provisional government, recall the factional fights out of which consensus eventually arose among the Zionists. The executive board of the World Zionist Organization kept its surface unity in the mid-1940s by demanding that there be a Jewish commonwealth in all of Palestine. Even as they voted for this formula, David Ben-Gurion and Nachum Goldman agreed privately to the partition of Palestine, and they informed the State Department of their agreement in late 1946, acting behind the back of the then leader of the Zionist movement in America, Abba Hillel Silver, who was an uncompromising maximalist. The Zionist movement formally accepted the principle of partition months later, when a Jewish state in part of Palestine had become the only possible political option.

For the PLO to accept the principle of partition and to establish a state on the West Bank and Gaza means that it must recognize Israel. Arafat is not at all like David Ben-Gurion, or Abdullah, or Sadat; boldness is not in his nature. The statements calling for peaceful coexistence by his immediate associates, Bassam Abu Sharif and Abu Iyad (Salah Khalaf), are trial balloons. Arafat has now moved publicly to identify with their position. He announced in Strasbourg on September 13 his acceptance of the partition of Palestine and his wish to establish a Palestinian state to live in peace with Israel; he even wished Israel a “Happy New Year” in Hebrew. He knows, of course, that such opponents as Abu Nidal and the Islamic Resistance Movement in the West Bank and Gaza remain in vehement opposition. The Palestine National Committee is scheduled to have a showdown meeting this fall, but that session keeps being postponed. When the meeting is finally held (I suspect that it will not take place until after the Israeli and American elections), it seems likely—or so well-placed Palestinians have speculated—that it will go to the brink of accepting the existence of Israel in language that the hard-liners both in the PLO and in Israel will not be able to dismiss—but only to the brink.

But, even if the PLO avoids making a formal decision soon, it seems beyond doubt that its principal leaders, including Arafat, want to settle for a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. Part of the evidence is in the present position of Feisal Husseini, the director of the Arab Research Institute of Jerusalem. Virtually all political leaders today in Israel, both Jew and Arab, know that he is the principal figure in the land who is linked to the PLO. Israel kept him for five years in a kind of house arrest in which he was limited to moving about by day only inside the city of Jerusalem. After a few months of freedom he was recently arrested again and jailed on unspecified charges of threatening public order.

Husseini was interviewed in June for the English weekly edition of Al-Fajr, an Arabic daily paper in Jerusalem. He said openly, for the first time, that he was prepared to accept the UN resolution that partitioned the land and to live in peace in a Palestinian state side by side with Israel. On July 27, 1988, Husseini came to West Jerusalem to a meeting sponsored by Peace Now, where he shared the platform with Israeli moderates. Husseini reiterated his commitment to the vision of Israel and a Palestinian state, beside each other, as the way to achieve peace. Not many hours afterward he was arrested. A Palestinian spokesman who advocates peace and the principle of partition is even more threatening to the policies of Israel’s present government than sloganeering rock-throwers in the streets.

I did not see Husseini in Israel this July, but I spoke at length with several other Palestinian leaders, including one or two of the generation under thirty. To be sure, there are many fanatics among the young men and women of the intifada who talk of wanting to wipe Israel out. But Feisal Husseini, Hanna Siniora, the editor of Al-Fajr, and Sari Nusseibeh of Bir Zeit University, are not an isolated triad of Palestinians who are known to the Western press and who talk reasonably for public consumption. They represent a body of opinion inside the undivided Israel. These Palestinians have no delusions about destroying Israel; they know that the choice of the Palestinians is between an ever bloodier riot and compromise—and they have chosen compromise.

The divisions in the PLO today are reminiscent of those in the Zionist camp in the years between 1945 and 1947. Most Zionists outside Palestine wanted all of Palestine for the Jews, and they succeeded in dominating the World Zionist Congress that was held in December 1946; most of the Jews in Palestine itself, who were suffering from guerrilla warfare, were for partition. Today most of the Palestinians who are carrying on the intifada on the West Bank and Gaza are reputed to want a quick solution through a Palestinian state, though fundamentalists have been circulating a document that denounces any alternative except jihad, Holy War, against Israel.6 The hard-line factions of the PLO, such as the group led by Dr. George Habash which is based in Syria, are bitterly opposed and will most likely split off from the PLO if Arafat takes the step of recognizing Israel, on the way to negotiating a Palestinian state. But for the Palestinians the consequence of heating up the civil war will be to provide the Israelis with a good conscience, and a large national consensus, for further military repression.

Israel may be farther along the road to the same conclusion than most Israelis have yet admitted to themselves. There is hard evidence for this assertion in the very polls that are being quoted as proving the contrary. True, when asked directly whether they are willing to allow a Palestinian state on the West Bank and Gaza, something less than three out of ten say yes, and twice as many say no. On the other hand, all of the current polls confirm that at least two out of three Israelis, including large numbers of Likud voters, feel that the West Bank must, at least, be redivided to free Israel of the pressure of its Palestinian population. Now that Hussein has refused to be responsible for this population, the Israeli majority is left with a choice between repression and a Palestinian state.

When faced with these choices Labor’s base among those who vote for it has remained stable in the polls; it apparently has enough votes to elect over forty seats in the Knesset, just as it did during the last four years. After Hussein’s speech, which supposedly left Shimon Peres without a foreign policy, the poll results on Labor’s support at the end of August were the same as those a month earlier. Labor has its own hawks, as I have said; but at least a considerable number of those who are continuing to choose Labor now are saying out loud that this is the party that is willing to make any reasonable deal, if necessary with the Palestinians, to end the conflict. “They will not,” one Labor politician told me, “hold Labor to our platform rhetoric that we should deal only with Jordan and never with the PLO—if the PLO is truly offering a deal.”

Everyone in Israel knows that de facto the land has already been redivided. The West Bank settlers who sent their children on a disastrous hike near Beita wanted to assert that “it’s our country, we will behave normally in our own land,” and such statements have a desperately insistent sound. Driving into East Jerusalem, the shops are closed and shuttered by noon, on orders of the leaders of the intifada. Despite the presence of Israeli patrols, East Jerusalem has its own form of Palestinian rule. It may be true, as Israelis insist, that many of the shopkeepers in East Jerusalem and throughout the West Bank and Gaza would prefer not to be forced by the intifada to continue the semi-strike that has been going on for months, but they have no choice except to obey the Palestinian underground, or their shops and homes will be torched. This reality, and the unpleasantness, and worse, of military duty in these areas, have had deep effects on the consciousness of Israelis. There seems no way to reverse the events of the intifada. There are no more Arab notables of the old school, such as Sheik Jabari of Hebron, with whom a comfortable deal can be made. That Israeli soldiers could somehow reconquer the West Bank and restore the status quo of last December street by street seems less and less likely. Meanwhile, quietly and insidiously, the numbers of Israelis emigrating is increasing. This is not new, but it is all the more upsetting now when the country as a whole feels itself more embattled than at any other time since its beginnings.

From the polls and my own talks with Israelis this summer, the following picture emerges: some 30 percent of the Israelis are willing to accept a Palestinian state on the basis of mutual recognition without asking many questions about what is ultimately in the hearts of the Palestinians. So long as the state would be demilitarized, this group believes that as time passes the simple necessities of maintaining a state of their own and living side by side with the Jewish state will make the Palestinians settle down, forget their past grievances, and turn away from the uncompromising factions that will continue to try to upset such a settlement. These Israelis believe, also, that their own extremists will fade in influence once a Palestinian state is established.

At the other extreme there are an equal number of Israelis who refuse to give any ground whatever. In the middle, another, decisive, third of Israelis is ambivalent: they want a settlement with the Palestinians, even one calling for a Palestinian national entity or state (there are of course many shades and gradations of this compromise position) but they do not believe that such a settlement should be made with the PLO. They hope to avoid dealing with the official and widely accepted leaders of the Palestinian national cause. Illogically, they would like to negotiate with nonnationalist Palestinians, that is with Palestinians who do not exist.

Part of the explanation for this attitude is to be found in the most basic issue of all between Jews and Palestinians, the question of legitimacy. Israelis have a bad conscience about Palestinians. They have never forgotten the Arab attack but they have repressed their share in making the defeat of the Arab armies in 1948 into a rout of civilians, and they want to believe that their own right to Israel is morally and politically unquestionable. Therefore, they hear all too acutely whenever it is said among Palestinians that their ultimate dream is to return not only to Ramallah and Nablus but to Haifa and Jaffa.

Polls of the Palestinians both inside Israel and among the refugees in Arab lands have shown a consistent vote of at least four out of five who say that their aim is the return of all the Palestinians to their former homes inside pre-1967 Israel. Thus by implication they still dream of the day when the State of Israel would, in fact, be dismantled. No one in Israel, even among the ultra-doves, forgets for very long that the announced purpose of the PLO, as stated in the Palestinian National Covenant, is to put an end to the State of Israel and replace it with Palestine, extending from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River.

On Nightline on April 27, 1988, Walid Khalidi, one of the most serious thinkers among the Palestinians, insisted to Ted Koppel that Zionism did not have “a right which overrode the rights of the indigenous population,” and an exchange with Koppel went as follows:

Khalidi:…We’re talking about what the basis of the Zionist claim to Palestine is. There are four bases. One is the divine argument. One is the argument from positive law, in other words, the League of Nations, the Balfour Declaration. One is the argument from natural law, that is, the need. One is the argument from historical connection. These are the four arguments. And each one of these is susceptible to scientific scrutiny. And each one of them can be looked at and studied like any argument, like any proposition. As far as the divine law argument, based on divine promise, that I’ve just pointed out, you cannot really uphold this because you can put your God against my God and then we are in the middle of a crusade and a countercrusade….

Koppel: …Among the four points that you have raised, the one point that you have not raised—which is really the cornerstone of all historical conquest—is that might makes right. Ultimately, what really counts is not the history, but who has the power, isn’t it?

Khalidi: Fine. All right. If we’re talking about the sword, that’s all right. I mean, I accept that. But I thought we were not talking about the sword. We were talking about the moral basis. And if the moral basis is based upon these four points, each one of them is susceptible to criticism. If we’re talking about the sword, then let’s talk about the sword.

Such remarks ring loud in Israel; they tend to drown out Khalidi’s elegant plea for Israeli acceptance of “symmetry of dignity” between themselves and the Palestinians, and his writings calling for peaceful coexistence between an Israeli and a Palestinian state.7

The statement circulated by the PLO spokesman Bassam Abu Sharif in June said:

We believe that all peoples—the Jewish and the Palestinians—have the right to run their own affairs, expecting from their neighbors not only nonbelligerence but the kind of political and economic cooperation without which no state can survive [my emphasis].

This tolerant sounding version of Palestinian Zionism, when read along with Abu Sharif’s assurances about the peaceful coexistence of two states in Palestine, seemed too good to be true, and it probably is. Arafat has not confirmed it; other Palestinians rejected it. Few Palestinians are likely to accept that the creation of Israel was an act of redress to the Jewish people for twenty centuries of being landless and powerless.

But the moderates on both sides have thus gone remarkably far during the last few months toward pragmatic mutual acceptance and recognition in public. In both camps some hard-liners are becoming more obdurate. The partition of Palestine now seems conceivable for the first time in over forty years, especially if the Great Powers come to the conclusion that the process should be helped, as they did back in 1947. Nonetheless, the intractable problem of legitimacy remains for both sides.

I do not believe the views of those in either camp who say that practical political arrangements should be made and that ultimate questions of mutual acceptance on the deepest level will solve themselves. The contrary is true: a majority cannot be mustered in Israel to accept a Palestinian state unless Israelis are assured that this would bring to an end the Arab moral assault on their most sensitive point, their legitimacy. One of the bitterest divisions inside Israel, between the religious and the secular, is deeply involved in this issue. Most of the religious Jews have no trouble asserting to themselves and to the world that the Jewish God gave them the land, and that all who dwelled in it for the last two thousand years were temporary so-journers whom He permitted on the soil while Jews expiated their exile. These religious Israelis have no problem of national legitimacy and most of them are not ready for moderate compromise either.

Most of those who are willing to make peace with Palestinian nationalism are secular Jews, whose claims to sharing in the Land of Israel are based on the need of the Jewish people for a national home of its own. The partition resolution was a kind of “affirmative action” by the international community and, as in every act of affirmative action, it created grievances that its beneficiaries have been reluctant to face. For many years Israelis talked only of “refugees,” not Palestinians. Golda Meier’s view that there simply were no Palestinians exhibited in its clearest form the defensive denial of the reality of Palestinian existence one still finds in Israel. It is a reality so troubling for many Israelis that it still must be deflected, or dismissed, or demonized by ascribing to virtually all Palestinians the character of bloodthirsty enemies—a stereotype the PLO too often confirmed by its terrorism.

The time is now past for pragmatic politics. The majority in Israel cannot even persuade itself that it is in its pragmatic interest to do business with the PLO even as a way of curbing the intifada and avoiding the Palestinian ultranationalists and the Muslim fundamentalists—as it once did business with Abdullah to avoid the Palestinian question. The leaders of the PLO will probably look for ways of adopting a position that will not drive their extremists out, and thus the PLO may avoid the issue of Israel’s legitimacy. The turning point that came with Hussein’s speech of July 31, leaving the Palestinians and the Israelis to work out their relationship directly with each other, demands nothing less than confronting fundamental issues between Israelis and Palestinians. It is an old Middle Eastern tradition that enemies do not end their quarrels with lawyers’ negotiations; they have a Sulha, a publicly staged act of forgiveness in which they wipe out past angers and begin anew in mutual acceptance. Such a Sulha must precede the negotiation for the final enactment of partition, for without it there will not be passion enough among the moderates of both camps to create the necessary majorities for such a settlement, and the result will be ceaseless conflict between two nations fought with more and more dangerous weapons.

Here the initiative belongs to Arafat and to his associates. The offer of a two-state solution will not be enough to keep Israel’s right wing from finding enough votes in Israel to veto the settlement. Within his own camp a simple offer to accept partition will cost him much. I doubt whether the offer of a final settlement with Israel will cost him much more, in divisiveness and even personal danger. Such a Sulha has now become the political and moral imperative for both sides.

—September 15, 1988

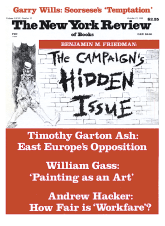

This Issue

October 13, 1988

-

1

Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem: 1947–49 (Cambridge University Press, 1987), see especially pp. 289–290.

↩ -

2

“The View from Cairo,” The New York Review of Books (June 26, 1980).

↩ -

3

Abraham Tamir, A Soldier in Search of Peace: An Insider’s Look at Israel’s Strategy in the Middle East (Harper and Row, 1988), pp. 99–100, 180.

↩ -

4

The Washington Post (September 3, 1988).

↩ -

5

Yedioth Aharonoth (September 9, 1988).

↩ -

6

The Washington Post (September 6, 1988).

↩ -

7

See “Toward Peace in the Holy Land, Foreign Affairs (Spring 1987), pp. 771–789.

↩