Difficulties with Girls, Kingsley Amis’s eighteenth novel, finally reveals him as the W.C. Fields of English letters. His comedy has always rested on his own droll taking-the-mickey technique. His prose swarms on to the page like clowns into the ring and clambers all over the characters’ food, clothes, interiors, and inadequately camouflaged intentions, mimicking their speech, facial expression, and body language:

While he spoke, Porter-King had been moving his lighter up and down in the general area of his right hip, perhaps polishing it against the ginger-coloured dog-tooth check, more likely because he fancied there was a little pocket in his jacket round about there.

Or:

“Mr. Valentine—“ began Patrick when the three were settled.

“I wonder,” said the man referred to, sounding as if he really thought it might go either way, “if I could persuade you to call me Tim?”

These examples come from Difficulties with Girls. But the merry hooliganism of Amis’s early novels have dwindled to a tetchy weariness, a kind of sod-you melancholy. Even the reprise of Jenny Bunn from Take a Girl Like You doesn’t seem to have cheered him up. Amis women divide into two categories: manipulative bitches and a much smaller one where compassion, humor, and understanding combine with extreme sexual desirability. The original Jenny has always been top of the second.

In 1960, when Take a Girl Like You appeared, she was twenty, and the story ended with her losing her virginity to the lecherous but quite decent Patrick Standish. Now it is 1968: Patrick and Jenny are married and have moved from a country town to London, and Patrick from school teaching to publishing. He is slobbier than before and more sophisticated. Jenny is as innocent as ever and much more pathetic because she has grown used to being deceived and neglected, longs for a baby, and can’t get pregnant. At twenty-eight she is as squeamish as she was at twenty. When Patrick tries to explain to her what homosexuals actually do, she can’t bear to hear it. Her dealings with them are another matter: Steve and Eric, perpetually bickering in the next door apartment, afford opportunities for Amis to take off gay behavior and talk, and for Jenny to be faultlessly tolerant and compassionate. She has become altogether faultless, a Victorian pulp heroine, especially in the penultimate chapter where Amis indulges himself with a positively Victorian tableau:

A narrow sunbeam rather theatrically lit up part of the front of the building, missing by some yards the figure of Jenny at the sitting-room window. One of her pot-plants was near her on the sill and she might have been attending to it just before, but she now stood looking fixedly downwards through the glass, perhaps not seeing much. Soon she dropped her head further, paused and slowly turned away in a movement that expressed for Patrick [unseen by her in the street below] all he had ever seen of resignation, disappointment and loneliness. He tried to swallow, and said “Like the base Indian” in a voice that made an old bag in a green check trouser-suit swing round and stare at him in an affronted way.

The next chapter and the book end with Jenny discovering she is pregnant.

Patrick’s face was covered with tears. He came and put his arms round her and just squeezed, and they stayed like that for some time.

“How wonderful,” he said. “For us both. I’d stopped hoping or imagining. You clever little thing.” He kissed her hands. “You’ve done it. Changed everything. You’ve saved us.”

Jenny was happy. She was going to have him all to herself for at least three years, probably more like five, and a part of him for ever, and now she could put it all out of her mind.

Or have we been led down a corridor of reflecting ironies, running from the theatrical sunbeam through the green check trouser-suit, the base Indian, and Patrick’s tears, to end up at Jenny’s modest but still probably excessive hopes? If so, the corridor is mined: there are bits of unexploded sentiment lying around. There were quite a lot in The Old Devils, two novels back; now they constitute a real danger.

The most sympathetic of the women in The Old Devils was understanding, kind, sexy, and well into middle age. Being older made her better able to look after herself than Jenny is; not just with men, but as a character in fiction. Jenny is just too much: devastatingly attractive (everyone tries to pick her up), “she looks, as well as beautiful, like someone who finds sex entirely natural and enjoyable, and to do with love.” These revolting words are addressed to her by Patrick, and so they too may be meant as another irony. One hopes so. But they’re still true, and Jenny is also monogamous and forbearing beyond belief: only right at the end, after a particularly elaborate betrayal by Patrick, does she contemplate leaving him; but then the prospect of the baby changes her mind.

Advertisement

A perfunctory story, but there is a subplot: the title Difficulties with Girls refers only ironically to Patrick’s difficulties, which are the opposite of what is usually meant by difficulties: too much success, not too little. Real difficulties—or at least he thinks so—are experienced by Tim, another of the Standishes’ neighbors. Tim finds women attractive, but after he’s been to bed with one he goes off her. He doesn’t really like female company. This is normal for Amis men, but it worries Tim. His analyst suggests he may be homosexual, and to test this hypothesis he gets Steve and Eric to take him to a gay club. Imbroglios and fist fights result, but eventually, egged on by Jenny, Tim returns to his estranged wife, another Griselda like Jenny but not so pretty. Tim is Jenny’s counterpart in innocence, only in his case innocence is a comedy turn.

Amis has lined up a row of bullet-riddled old targets: the London literary scene with special reference to publishers and their ghastly parties, psychiatry, and modern education. The little brats in the children’s hospital where Jenny teaches whine and pick their noses because their parents have brought them up on permissive theories of child rearing; while Patrick has had to give up teaching altogether because his subject—the noble study of classics—is being phased out of the curriculum. “Well, what would you?” he says. “The bloody world’s moved on without consulting us, as Horace had it.” Even sex isn’t what it used to be; though there, according to a best-selling septuagenarian lady novelist, the decline set in earlier, with D.H. Lawrence: “He invented having to get it right when you went to bed with somebody,” she grumbles.

A very moot point in a novel where the main issue seems to be getting it right between the sexes. Jenny is the male chauvinist pig’s dream girl, forever making cups of milky coffee for her circle of male admirers, tormenters, and lame ducks. She gave up teaching full-time in order to have more time to be a good wife. So she has more time to be lonely and miserable. Amis seems to approve her decision. Or does he? His apparently most antifemale novel, Stanley and The Women (1984), was interpreted by Professor Marilyn Butler as a defense of women against men. Amis is said to have thought she was barmy: nevertheless, there are no difficulties about reading Difficulties with Girls as a savage attack on male selfishness and exploitation of women.

Amis’s beery literary persona and tweedy diction have helped to persuade us that he’s a misogynist. But he is really a misanthropist. Women are ghastly but men are ghastly too; so we should as far as possible forgive each other our ghastliness. And there are one or two good women around to encourage and redeem—Madonna figures like Jenny. Up to a point, it’s really a quite Christian position, with the transcendental part left out.

For Marianne Wiggins, forgiving doesn’t arise. She too writes from rage, but hers is at the blazing stage. What enrages her is male chauvinism, white chauvinism, and to a lesser degree human chauvinism against animals. She goes on about them shrilly and relentlessly. One puts up with it and a lot of other irritations because John Dollar, right from the ghoulish and inscrutable flash-forward opening, is mesmerizing and quite unlike anything else.

Except in the sense that it’s a female variation on Lord of the Flies. Instead of schoolboys it maroons a group of English schoolgirls on a tropical island. Gradually they turn into savages and the two eldest begin to eat the sole male survivor of their shipwreck, a sea captain called John Dollar. His spine is broken, so he is paralyzed from the waist down and can’t feel them digging bits of flesh from his legs. They do it at night so the other children can’t see. Wiggins spares no effort to make one’s flesh creep, and her success is stunning.

The story begins just after the First World War with a young English war widow, Charlotte Lewes, traveling to Rangoon to take up a post as governess to the children of the British colony there. A woman with progressive attitudes, she goes native as far as is compatible with her job and to bed with the American John Dollar. He is good at sex and a student of Leonardo, which gives Wiggins an excuse to decorate her margins with quotations—in French, figurezvous—from The Notebooks.

Advertisement

The parents of Charlotte’s charges are an insensitive, loutish, snobbish, arrogant bunch, and their smug and domineering attitude toward the Burmese has already infected the older children. The disaster that eventually destroys everyone except Charlotte and one little girl is caused by mindless imperialism: to celebrate King George V’s birthday a party of British men, women, and children set out from Rangoon to claim an uninhabited Andaman island and name it after the monarch. The expedition is to be a jolly patriotic picnic, all flags and hampers. But a tidal wave smashes the boats, drowns some of the party, and leaves the rest marooned in several separate groups. Charlotte is washed up alone. The children—all girls: the boys have been drowned—find one another one by one and then stumble upon the helpless John Dollar. The other men are roasted and eaten by raiding cannibals. High on a distant cliff the little girls “watched their fathers writhe and pop and as they watched, the wind brought an aroma to them on the hill.” After the cannibals have sailed off, the children go down and collect their fathers’ bones for jewelry and talismans; then they daub themselves with the cannibals’ excrement—a symbolic rite.

The two eldest girls draw up rules and dragoon the other children. They are the daughters of a clergyman and an Old Etonian colonial officer. Church and state. The officer’s daughter, Amanda, manages to preserve embers from the cannibals’ fire:

Since the coming of the fire, the two of them have acted strange, not like the rest of them, but like owners, Oopi [one of the younger children] thinks, do this, do that, like sergeants, or superiors or kings…. Amanda keeps the fire, Nolly [the clergyman’s daughter] is in charge of John. Every day there are his bathing and his quinine rituals, his turnings, his tonsure, his decoration and his eucharistic feedings. Nolly is in charge of these, in charge of their performance and their liturgy, and excommunication from them is the punishment that she exacts when she is crossed.

One by one the younger children die of hunger or get lost in the jungle, until only Nolly and Amanda, Gaby and Monkey are left. These two are Wiggins’s favorites. They are not English, of course: gentle, affectionate Monkey is a half-Indian child whom the others despise; brave, resourceful Gaby chatters in her native Portuguese, exasperating the reader a bit more. When they realize the other two are eating John, Gaby and Monkey run away. Amanda and Nolly chase them. Gaby climbs a tree and they set fire to it. Monkey escapes. Eventually she finds Charlotte and leads her back to the camp. Charlotte kills Nolly and Amanda. John is already dead and Monkey helps Charlotte to bury him.

The final episode is not described and only alluded to in the first chapter in such a stealthy way that you could easily miss it. Six decades have elapsed since Charlotte and Monkey were rescued, and they have spent them as hermits on a Cornish cliff. Now Monkey is leading a donkey with Charlotte’s dead body on it into St. Ives to get her buried. The parson refuses because Monkey can’t prove she was a Christian (very implausible behavior on the part of the Church of England in the 1980s). So after dark, Monkey buries Charlotte herself.

In case one hadn’t noticed the biblical implications of the donkey and the clandestine burial, the opening chapter is labeled (in the margin) “Last Act of the Apostle.” In fact, Monkey isn’t an apostle at all: she carries no message, though she may be a disciple. Wiggins isn’t always very well informed about the meanings of her meanings. Charlotte certainly seems to stand for a kind of loving, liberated, sensual feminine principle, nonviolent in spite of her lapse over Nolly and Amanda. That was understandable under the circumstances; her abduction of Monkey to England is less so, especially as Wiggins has been at pains to demonstrate the loving attachment between Monkey and her singleparent Indian mother in Rangoon. Charlotte should have restored her after they got off the island. It’s not the reviewer’s business to tell characters in a novel how they should behave, but Wiggins does not seem to have noticed that taking children from their mothers is just about the most chauvinist thing you can do. Though exemplary compared to the other English women, Charlotte is not supposed to be a Messiah, after all.

Wiggins’s inconsistencies and affectations are absurd. John Dollar often reads alarmingly like the manuscripts that Patrick Standish, in his professional capacity, enjoys rejecting. Her prose is sometimes careless and sometimes overdecorated with adjectives like “murrhine” and “vitelline,” and she insists on spelling the preposition round ’round (“It turns ’round”). She has quite a fetching sense of humor, mostly black, but it doesn’t stop her producing pulp like: “His eyes were hard. His hands were used to halyards but not unused to women.” And she hates the adult British so much that it gives her a cloth ear for their talk. She should have tried listening to The Raj Quartet.

The children’s idiom, on the other hand, is poetic, sinister, and funny, even if it sometimes misses cuteness by a whisker: a snake

smiled and Oopi saw it held a heron’s egg between its fangs.

Its smile was meant to let her know it could hinge its thorny mouth on anything, the earth, the sky, her tiny heart.

Its smile was meant to let her know that it could slither in and eat her inside-out.

She thought: if it does then I’ll be dead at seven-and-a-half years old, which is not as young as some girls die, but it was younger—much—than she had ever planned.

But Wiggins’s real forte is sensation: heat, lassitude, exhaustion, exhilaration, pain, sand under the feet, water on the skin, unripe banana in the mouth, objects taking shape on the horizon. And sex:

He expected women to be nervous, quirky, exercising fluttery, flirtatious touch—he had never known a touch like Charlotte’s, all-encompassing, compassionate yet startling. She was like the sea itself, an even wash across his senses, sometimes merciful, expansive, never calculating, often violent, never still. Hers was a touch of shoals and rills, a touch known only at the depth of nature where the surface of all things combines with slippery ease, seeming to be seamless.

Whatever Patrick Standish might think, this passage—and others—seems a successful attempt at crossing some kind of frontier of perception. It is Wiggins’s specialty, and even more effective when she’s dealing with horrors: she begins by making one’s scalp crawl with physical revulsion, then leads one by an ever clammier hand into a state of existential shock. One has to agree with the blurb that John Dollar is “a literary tour de force.” It’s too soon to say whether it’s “an unforgettable read,” but it might well turn out that way. Nightmares, possibly.

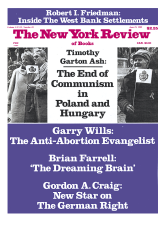

This Issue

June 15, 1989