In response to:

In Gorbachev's Courts from the May 18, 1989 issue

To the Editors:

George Fletcher’s description of a criminal court in Kiev [NYR, May 18] contrasts the way criminal cases are dealt with in the Soviet Union with the way similar cases are handled in the West. He criticizes the Soviet system of procuracy whereby an official investigates the charges before the hearing and decides whether or not to bring the case to trial and what charges to proceed with. The respect accorded to this official and the way his or her determination largely controls the subsequent proceedings is in marked contrast, according to Fletcher, with the presumption of innocence and the adversarial character of criminal proceedings in this country.

Professor Fletcher’s comparison is misleading in two ways. First, he misleads readers by omitting to mention that systems of procuracy are found not only in the USSR but also in most legal systems in the civil law family: for example, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, even Scotland. He makes it sound as though this (arguably prejudicial) preliminary investigation is distinctive of Soviet communism rather than characteristic of every legal system in Europe and America apart from England, the US and parts of Canada. Certainly, the procuracy differs in its operation from system to system, and Fletcher points out a number of defects in the Soviet version. But the appropriate recommendation would be to urge reforms along the lines of similar systems in Western Europe—reform within the parameters of this legal tradition—rather than insist parochially that perestroika means making Soviet institutions more like American ones.

Second, we have doubts about the reality of Fletcher’s contrast between the inquisitorial system of the USSR and what he calls the “genuinely adversarial” system of the US. Certainly the model of adversarial trials and due process is an important image for law professors whose attention focuses on the stern requirements imposed by appellate courts on criminal procedure in this country. That image is also pervasive in our culture. But it has very little to do with the way most cases are actually dealt with in our criminal courts. Close to 90 percent of people accused of crimes plead guilty in the United States. Prosecutors unhappy with plea bargaining retain considerable control over charging practices and have sometimes instituted “on the nose” charging, whereby a charge is not altered from arraignment to disposition. In many jurisdictions it is common to reduce the number of charges but not the seriousness of the first charge. (It is the latter that makes the most difference in penalty.) Defense attorneys participate in settling on a story that gets what they believe is a fair penalty for their clients. All this looks strikingly like what Fletcher deplores as the procuracy’s control of cases, in reality if not in the institutional rhetoric.

Professor Fletcher disagrees with what the Soviet Union defines as crimes and with the penalties imposed for them. That is fine. He also disagrees with certain aspects of their trial and pre-trial procedure. That is fine too, but it does no one any good to perpetuate ideological hostilities by contrasting the reality of one system with a rosy self-image of another. And it does no one any good to neglect the possibility that the legal systems of some of our NATO allies might offer better models for Soviet reformers to aspire to than a system like ours which is alien to theirs in its institutional traditions and uncomfortably close in the way it actually deals with people.

Susan Sterett

Department of Political Science

SUNY Binghamton

Jeremy Waldron

School of Law

University of California, Berkeley

George P Fletcher replies:

Susan Sterett and Jeremy Waldron remind us that the Soviet system of criminal justice has its roots in the continental inquisitorial system. Nothing I wrote contradicted this historical fact, and it in no way justifies practices that liberal reformers in the USSR have been engaged in trying for decades to reform. Indeed virtually all European systems have been in a process of evolution toward adversarial proceedings, based on parity between the powers of the prosecution and those of the defense. The process of evolution requires that some functions, such as ordering preventive detention and issuing search warrants, be transferred from the prosecution to the judiciary. This transfer has occurred in West Germany, to a lesser extent in France and Italy, and not at all in the Soviet Union. Strengthening the adversarial nature of the proceeding requires that the defense be free to prepare its case for trial by interviewing witnesses and carrying on an independent investigation. These powers of the defense are assumed in West Germany, but not in the Soviet Union.

Soviet legal reformers are only minimally informed about legal developments both in Europe and the United States. They think of themselves as developing a genuinely socialist legal system, not another version of the European inquisitorial system. The struggle for the presumption of innocence—code words for containing the procuracy and strengthening the role of the defense at trial—is carried on without appealing to foreign experience. Professor M.S. Strogovich, who began this fight in the late 1940s, could not have cared less about the imperfections of Western systems of criminal justice. When now President Gorbachev recently endorsed the presumption of innocence at the 19th Party conference, he was not deceiving himself with a “rosy image” of justice in New York. He was lending his personal weight to the resolution of a struggle within the Soviet system.

The Sterett-Waldron skepticism about criminal justice in the United States could hardly dissuade the Soviet reformers from carrying on their fight for a strong defense, a limited procuracy, and an adversarial trial. We act unjustly toward these reformers if we dismiss their efforts as sociologically naive or out of phase with their history. Rather than “perpetuate ideological hostilities” or, I might add, political sympathies, we should listen to what the reformers are telling us about their own system.

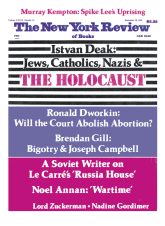

This Issue

September 28, 1989