A historian of contemporary China who is considering the events of three years ago, of ten years ago, of twenty years ago, must feel dizzy: each time, it is the same story, the plot is identical—one needs only to change the names of a few characters. The grim merry-go-round leads nowhere; it merely spins, ever more squeaky and rickety; the bloody contraption can only crush with increasing brutality a populace thirsting for freedom.

World opinion was revolted by the Peking massacres of June 1989. Our age, which should be quite blasé in the matter of atrocities, discovered a new dimension to horror as it watched this seemingly unprecedented phenomenon:1 a government that declares war on its own people, and unleashes an army of murderers against the peaceful and defenseless crowds of its own capital city.

The massacres stunned the world—and yet they should not have surprised anyone.2 The butchers of Peking are entitled to feel genuine puzzlement in the face of the indignation expressed by international opinion. Why should foreigners suddenly change their attitude toward them? What was so new in the June atrocities—which, after all, were still performed on a fairly modest scale, when compared with similar operations previously carried out by this same regime?

In fact, it is not the nature of Chinese communism that took a drastic turn for the worse in June; simply, it is the accuracy of Western perceptions that suddenly improved. Well before they took power, the Communists considered murder as a basic political device—and I mean murder in its most diverse forms: individual or collective, methodical or random, public or secret, aimed at dissidents to uproot opposition, or aimed at innocents to cow everybody. This method had already been vigorously implemented twenty years before the establishment of the so-called “People’s” republic. (For instance, the notorious massacres of Futian took place in 1930.)

At its beginning, the Chinese Communist movement was fired with genuine revolutionary ideals; it sought social justice passionately and succeeded in mobilizing the generosity and courage of a moral and intellectual elite. From the very start, however, it carried within itself the seeds of its eventual corruption; the Communists always believed that mankind mattered more than man. In the eyes of the Party leaders individual lives were merely a raw material in abundant supply—cheap, disposable, and easily replaceable. Therefore, quite naturally, they came to consider that the exercise of terror was synonymous with the exercise of power. If, from time to time, a Communist government could not kill its citizens, how would you expect it to govern?

Mr. William Hinton, the well-known author of several books on contemporary China, was in Peking at the time of the massacres. I read in the newspapers that he strongly denounced these atrocities. One can only share his indignation—but at the same time, the way in which he expressed his feelings seems to betray a remarkable (yet typical) confusion of ideas. He said that the leaders who ordered the massacres “are not communists; these people are fascists!“

One can throw many accusations at the Chinese leaders. If there is one thing they cannot be suspected of it is to have forsaken their unswerving loyalty to communism. Actually the very problem is precisely that they obstinately behaved as pure Communists. To brand them as “fascists” is to borrow a rather dim candle to light up the picture. From a Communist point of view, it would not even be possible to condemn the massacres’ stupidity. Not only were they necessary, but also their logic was impeccably Leninist.

The tactical flexibility of communism is considerable, but it is also entirely subordinated to a strategic imperative that is essential and immutable: in any circumstance and at any cost, political power must be retained in its totality. This rule is absolute, it tolerates no exception and must take precedence over any other consideration. The bankruptcy of the entire country, the ruin of its credit abroad, the destruction of national prestige, the annihilation of all efforts toward overture and modernization—none of these could ever enter into consideration once the Party’s authority was at stake. (Besides, in their economic and diplomatic relations with the West the Chinese leaders were probably not risking much; in this particular occurrence they may have made many miscalculations, but they have shrewdly assessed the actual limits of the memory and the indignation of democratic governments.)

As Bernanos observed, “Massacres are always committed out of fear.” The great fear that overtook the geriatric rulers in Peking reached panic proportions when they saw the entire nation rallying round the Tiananmen demonstrators and an alliance being formed between the students and the workers. The day when the demonstrators succeeded in holding martial law in check and in making the army waver in its determination, their fate was sealed. By the use of irreparable violence, a moat of blood was created in order to isolate the soldiers from the people. (It remains to determine what sort of role was played behind the scene by the security organs, which reaped the only benefits that could be derived from the crisis; to what extent was Deng deliberately fed wrong information? The secret police appears to be the real winner of the entire operation.)

Advertisement

The hot violence of the massacres has now given way to a cold terror—even more fearsome, since it is systematic and efficiently organized. In this new stage, there is no more room for messy and random improvisations; an appearance of order has been reestablished, the last bloodstains have been carefully scrubbed, the streets look neat and clean; and already a few foreign visitors—businessmen and politicians—are reappearing; they return to sit at the banquet of the murderers, and meanwhile, in the cellars of the secret police, with one bullet in the back of the neck, the youth, the intelligence, and the hope of China are being liquidated.

Twenty years after the storms of the “Cultural Revolution,” a fragile elite of intellectual and political critics had miraculously emerged again; now, they have been obliterated with one single blow. The police, who were keeping records on all the thinking minds of the country, had been waiting for such an opportunity to get rid of them all at once. The talent and expertise which China needs in order to modernize have now gone underground—or they survive only in exile: tens of thousands of scholars and scientists who were abroad at the time of the massacres dare not return home, knowing too well the fate which is awaiting them there. Today China is a nation without brains. What future prospects can a big country on its way to modernization still entertain after suffering such a lobotomy?

This issue does not appear to worry unduly the thugs who are now controlling China’s fate. Their only concern is to apply Lenin’s recipe: “A regime which is prepared to use limitless terror cannot be overthrown.” Indeed, nothing else seems to matter now—this brute repression does not even attempt to cover itself with the scantiest ideological rag; China’s senile despots are unable to articulate a single idea. Leading articles in The People’s Daily can only recycle a dusty jargon that dates back to the days of the “Cultural Revolution” and in order to denounce today’s enemies, they have to rehash the very abuse that Mao originally used to hurl at Deng Xiaoping!

In principle, the Peking massacres were in complete conformity with what could be expected from Chinese Communists. Actually, it would have been more surprising had they not taken place, for this would have amounted to the government’s announcing its own dissolution. The massacres were new only in one respect, but this particular innovation had momentous repercussions. From beginning to end, the atrocities took place in front of foreign television cameras and under the eyes of the international press. Formerly, in all similar operations, Communist leaders always observed carefully the traditional rule which prescribes “beating the dog behind a closed door” (guan men da gou). In June 1989 in Peking, for the very first time, the gates of the slaughterhouse remained wide open.3 (Is this perhaps what is called “the open door policy”?)

The extraordinary impact of television also has a frightening aspect. For millions of spectators the events that are seen on the small screens take on flesh and carry weight; they can upset world opinion and ultimately affect the policies of democratic governments; conversely, this also means that whatever has escaped the eyes of the camera is virtually erased from reality, or doomed to vegetate in a limbo of the collective consciousness, where it cannot generate emotions or mobilize minds. What happens outside the range of the cameras does not really happen. Thus, for instance, over the years, Chinese Communism could liquidate more than a million Tibetans—yet this fact never seriously impaired China’s prestige and international credit. Why? There were no television cameras on the spot. Nor were there any cameras to witness the massacres of the “Cultural Revolution” in which more than half a million lives were lost. In 1968, when the army began its suppression of the Red Guards, slaughters similar to those which we just saw in Peking took place in dozens of cities. (After one such wave of executions, rivers in southern China were clogged with so many corpses that, on the beaches of Hong Kong, some eighty miles away, the tide would every day bring us scores of dead bodies.) From the beginning these facts were well known; information was plentiful and easily available. And yet, ten years after these events, their reality had still not penetrated the consciousness of the Western world; as a result, when Mao died, the leaders of our democracies could wholeheartedly pay a respectful homage to the lunatic old tyrant, whom they described as “a guiding light for all mankind.”4

Advertisement

Shortly before his tragic death, the Soviet dissident Andrei Amalrik became interested in Chinese politics. Some twelve years ago I heard him make a striking observation: he remarked that China was much more “advanced” politically than the Soviet Union (I should rather use the French word avancé, which can also apply to the overripe condition of a cheese, or of a corpse). As Amalrik put it, the misfortune of the Soviet Union was to have won the war, whereas the good luck of China was to have lost the “Cultural Revolution.” Its victory over Nazi Germany vested Stalinist Russia with a sort of self-righteousness and moral confidence which for a long time precluded any clear awareness of its fundamental failings; the regime found itself confirmed in its worst errors, and as a result, the much needed reforms were indefinitely postponed. In China, on the contrary, the frightful catastrophe of the “Cultural Revolution” accelerated the disintegration of the Communist system. For a while, the Party was completely destroyed. Though it was eventually rebuilt, it never recovered its prestige and authority; these were irretrievably discredited. Yet the crisis of the “Cultural Revolution” did not merely expose the moral and political bankruptcy of the regime, it also had positive results: it produced a new breed of citizens—bold and aggressive. People of such caliber can become heroes, they can also become bandits, but certainly it will never be possible again for the regime to cow them into the meek and passive docility of their elders.

The May 1989 demonstrations marked the apex of a long evolution that originally sprang from the “Cultural Revolution,” and subsequently found its expression in a series of spontaneous movements, with ever broadening popular support and increasing articulateness. First, there was the earliest of the great Tiananmen demonstrations, on April 5, 1976, which, shortly before Mao’s death, dared denounce his tyranny. Then, in 1979, there was the “Peking Spring,” with the activities of the “Democracy Wall,” which represented a deepening of democratic aspirations. Without the previous experiences of the “Cultural Revolution” the movement for democracy would probably never have been able to develop on such a scale, and with such speed and audacity—yet its greatest merit is that it succeeded in largely shedding its very origins. In this respect, the personal evolution of a man such as Wei Jingsheng is exemplary: arrested after writing his eloquent appeal for democracy in China, he was finally to become a hero and a martyr of the “Peking Spring,” during the nonviolent struggle for democracy—and yet, ten years earlier, he had been a leader of the Red Guards.

By a cruel paradox, whereas an elite of China’s youth effectively outgrew and discarded the heritage of the “Cultural Revolution” (which had originally launched them into politics), Deng Xiaoping and his colleagues, after having been the victims of the “Cultural Revolution,” now remain its prisoners. They fear and hate the “Cultural Revolution,” yet, at the same time, they have retained its language and methods—as was shown in the Peking massacres and in the wave of denunciations, lies, and terror that followed it. The ferocity with which they crushed the demonstrators in Peking cannot merely be explained by the memory of the humiliations which they had suffered at the hands of the Red Guards. How could anyone ever have confused the peaceful and smiling crowds of 1989 with the fanatical hordes of 1967? Could there be anything in common between the young rebels who had dragged them down twenty years earlier and today’s nonviolent patriots? A profound metamorphosis has taken place from one generation to the next, but beyond this transformation, Deng and his henchmen confusedly identified a menace—which their blind obstinacy only succeeded in precipitating: they know they are facing the irrepressible surge of the tidal wave which is going to sweep them away tomorrow, together with the last remains of Chinese communism.

Unfortunately, its poison might outlast the beast itself. The legacy of such a regime can be even more evil than its rule. The collapse of the present government is ineluctable; what is to be feared is that, after forty years of economic mismanagement, in the present circumstances of overpopulation and poverty, with a population brutalized by four decades of relentless political terror, worse horrors may follow.

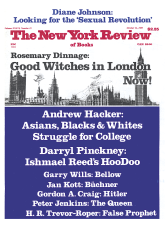

This Issue

October 12, 1989

-

1

In fact, it is unfortunately not new—neither in China (as I shall try to show here), nor elsewhere in the world. Yet who remembers the Hama massacres in Syria, where President Assad slaughtered 25,000 fellow citizens in 1982? One has perhaps not yet completely forgotten how, last year, the Iraqi government undertook to annihilate with gas and chemical weapons, entire villages of its Kurdish minority—though the only reaction from Washington was to double export credits granted to Iraq, while France, West Germany, and England maintained their friendly relations with Baghdad.

↩ -

2

Presumably President Bush at least was not surprised—though perhaps not for a very good reason. If I am to believe a report from The Washington Post (reproduced in The Guardian Weekly, Vol. 140, No. 27, July 2, 1989), President Bush discovered during his stay in China that, owing to “cultural differences,” “the Chinese hold life less dear [than those in the West].” Thanks to these wonderful “cultural differences,” one may also suppose that the Chinese hurt less when they are being crushed by tanks and incinerated alive with flame throwers.

↩ -

3

It is difficult to determine why this attitude was adopted. Perhaps, within the bureaucracy, some officials who were opposed to the repression deliberately sabotaged the implementation of measures to control the activities of foreign journalists. Perhaps also the gerontocracy in Peking has become so anachronistic that the leaders are not fully aware of the role being played by the media at the end of the twentieth century. For Deng Xiaoping and Yang Shangkun, television is probably a sort of machine that enables you to watch Mickey Mouse at home.

↩ -

4

The expression was actually used by Mr. Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. It is not even the silliest thing that was said at the time.

↩