In response to:

Affirmative Action: The New Look from the October 12, 1989 issue

To the Editors:

Andrew Hacker’s review survey [NYR, October 12, 1989] on affirmative action in college and university admissions omits a crucial factor. Although he draws attention to the conflict between the ideal of equal opportunity and the widespread practice of preferential admission, he never mentions any moral or legal right not to be discriminated against on account of race, color or national origin. Is there such a right in the United States? Whether preferential admission for blacks, Hispanics and other minorities is justifiable depends in large part on the answer to this question.

The issues are well illustrated by the situation described in the report, Freshman Admissions at Berkeley, reviewed in Professor Hacker’s article. Does Berkeley believe in a right to racial and ethnic non-discrimination? The report does not say. If such a right exists, is it violated by the Berkeley admissions process as described?

Berkeley measures academic qualifications for admission by an “academic index,” combining grades and test scores. For more than half the applicants admitted, the decision depends entirely or predominantly on their academic index. The rest belong to categories—some racial or ethnic, some not—designated for preferential treatment. Most recipients of preferential treatment rank in the top eighth of their high school graduating class, a traditional requirement for admission to a branch of the U. of California. But to enter Berkeley, the most prestigious branch, without preferential admission, applicants nowadays must be in the top 3 or 4%.

In the fall of 1988, out of 7700 admitted as Berkeley freshmen about 2300 received preferential admission because they were black, Hispanic, American Indian or Filipino. They were selected, because of their race or national origin, instead of 2300 white (non-Hispanic) and Asian (non-Filipino) applicants with significantly higher academic indexes. Thus, in one round of admissions at one university the right to racial or ethnic non-discrimination, if it exists, was violated in the cases of 2300 persons.

In the 1960s a powerful American consensus assumed that all persons have a moral and legal right to racial and ethnic non-discrimination. As an institution supported in part by federal money, Berkeley is subject to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which forbids discriminating against, on grounds of race or national origin, any applicant for admission. But this prohibition, though absolute on its face, has in effect been amended through executive and judicial interpretation, uncorrected by Congress, to permit racial and ethnic discrimination when it is part of an acceptable affirmative action plan.

If such discrimination is now legal, is it moral? By their actions, thousands of institutions now practicing racial and ethnic preference seem to say yes. How does their rule, that discrimination is wrong except when part of an affirmative action plan, differ from the much older rule, that discrimination is wrong except when the people in charge wish to discriminate? If they answer that their affirmative action plans meet fair and impartial criteria, let the criteria be specified: Which social ends justify discrimination and which do not? What qualifies a racial or ethnic group for preferential treatment? What determines the degree of preference and how long should it continue? If any group is immune from being discriminated against, what qualifies it to be so?

The colleges and universities that deny, to some of their applicants, the right to non-discrimination should be honest enough to say so. For example, “As compensation for past discrimination against (racial/ethnic groups A,B,C…) and to increase the proportional representation of (A,B,C…), this institution discriminates in favor of persons belonging to (A,B,C…) and against persons not belonging to (A,B,C…)”

Curtis Crawford

Charlottesville, Virginia

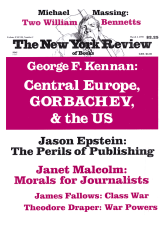

This Issue

March 1, 1990