When Joseph Conrad distilled the elements of human existence into the blessing of illusions and the curse of fact, he anticipated Soviet history, whose epitome The Museum of Modern Art provides with its freshly opened exhibition, Architectural Drawings of the Russian Avant-Garde. The Modern’s show runs from 1918, when the Soviet Revolution was newborn, through the scant sixteen years that were enough for it to swell into the pomposities of middle age.

Revolutionary histories have a habit of beginning where every attuned spirit knows that the future is glorious but has no tangible idea of what it will look like. We ought not to be surprised, then, that the earlier works in the Modern’s display have none of the disciplines of scale and line we associate with architectural draftmanship. The project that Vladimir Krinsky labeled Temple of Communion Between Nations is an abstract drawing that the artist could have as plausibly called Study in Form and Mass (3). Communal House suggests nothing so much as one of those old French towns whose roofs and frames Georges Braque used to heap together and then send running up a hill.

Illusion has willed away fact. The architect has no need to plan, since this communal house is not yet abuilding and will never be. It is a house of Krinsky’s imagination and yet so solid in its maker’s mind that he has conjured up structures settled and grown old together so long that the only eyes that can see them in a new way would have to be a Cubist painter’s.

Krinsky did not approach the drawing board as an architect but as an adept pupil of the Russian Constructivist school. Until now Constructivism had seemed to some of us only a starveling country cousinship to Braque and Picasso; but here it takes on a far grander pathos with our recognition that Constructivism is the art of those with no chance to construct.

The Soviet architects began with modest and rather homely ideas and were soon conscripted to bulging with grandiose ones, and in few cases did any get built at all. The fault at the beginning was less in the revolution’s narrowness of vision than in its circumstances.

Catherine Cooke points out in the catalog that splendidly accompanies the Modern’s show that civil war had depleted the Russian construction industry of most skills and all materials except timber and concrete; and that, as late as 1926, the Soviets had nothing to gain from European modernism because they didn’t even have plate glass. When materials fit for the dream of the New came to hand in the Thirties, prejudices for the Old had embedded themselves too deeply for change.

Lenin’s distaste for the bourgeois had not taken him forward but back, to the ducal style. A preference for other centuries seems inevitably to carry the mind to earlier and earlier times until Lenin’s preference for Renaissance palaces was succeeded by Stalin’s for Pharaonic monoliths.

The Soviet vision of monuments that their revolution deserved would remain mostly unrealized. The sketches bravely dashed off when there was no stuff available for the works progressed to elaborate submissions of architectural drawings to juries that didn’t know what they wanted. The architectural competition had replaced the materials shortage as cause for non-building.

The Palace of the Soviets and the Commissariat of Heavy Industry are here embalmed as perspectives of grand vistas with a future existence no more real than that of Krinsky’s Communal House. The only difference was the loss of charm and proportion and the arrival of confusions so disorderly that the Palace of the Soviets’ jury seriously considered a replica of the Doge’s Palace in Venice before accepting a pile crowned with a statue of Lenin “the height of a twenty-five-story skyscraper” and with an index finger twenty feet long. What must henceforth be must be gigantic; and, as usual with the revolution, it would never be at all.

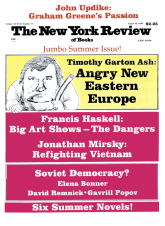

This Issue

August 16, 1990