In response to:

Wind from the Prairie from the September 26, 1991 issue

To the Editors:

Elizabeth Hardwick’s recent essay on the so-called “prairie poets” [NYR, September 26] contains several errors of fact and fallacious assumptions about my father, Edgar Lee Masters, and my mother, Ellen Coyne Masters, which compel me to offer your readers these corrections.

My guess is that Hardwick has put too much credence in the memoir published by my half-brother, the late Hardin Masters, and that she accepted some of the half-truths and calumnies that unhappy man put into print. She might have done some double-checking.

First and simplest, though most basic, is the date of my father’s birth. He was born in 1868 and this year is proved in all kinds of places including the birthpage of the Masters family Bible as well as passports issued to him in the 1920’s. Current, authoritative references also give this year. Why and how the year 1869 was promoted, and by him no less, is a story too long for here but can be found elsewhere.

More complicated to unravel for your readers are the different innuendoes and outright slanders that circulated in the wake of my father’s divorce from Helen Jenkins Masters in 1922 and which have been given a refreshed currency by Ms. Hardwick.

To begin in the middle, my father did not “die in want” nor was he “packed off to a nursing home” nor was he “rescued to die in a nursing home.” These dramatic phrases compress the time and circumstances in a way that is only equaled by Ms. Hardwick’s own economical fiction.

When my father collapsed in 1943 at the Hotel Chelsea, my mother had been teaching at the Bentley School on West 85th Street, New York City for several years. Not Pennsylvania. He was not packed off to a nursing home in Pennsylvania but nursed back to health that spring of 1944 in New York City—in an apartment in the East 80’s—while my mother pursued her professional duties. That summer, he accompanied my mother to North Carolina where she had been hired by the Charlotte Country Day School to create an English Department. At this point, my father was walking, talking, eating and even doing a little writing—like most everybody.

A couple of years later, he accompanied her to the small village of Rydal, Pennsylvania, where she was hired by the nearby Ogontz Junior College. He was still walking, talking, eating and doing some writing. It was here in 1950—six years after they left New York City, though returning for many visits with friends in the interval—that my father died at the age of eighty-two. Yes, it was indeed in a nursing home, for the last six months of his life he was bedridden and required round the clock care. He was, up to the hour of his death—not walking—but talking and eating and reading and even doing some poems.

No one can say—especially those who visited us in North Carolina or in Pennsylvania, or who saw my parents in New York City between 1944 and 1947, that he wanted for anything: food, comfort, company, or medical attention. All this provided by the efforts and abilities of Ellen Coyne Masters.

The “younger woman” epithet has slandered this same woman since the scandal of the divorce of that first marriage, a slander promoted by my half-brother in his published memoir and now passed along to your readers by Elizabeth Hardwick.

For, in truth, the woman who caused the final rupture of my father’s first marriage—if indeed she can be blamed—was a woman of his own generation, the wealthy widow of an Indiana banker. Their affair had gone on for many years; they had even secretly gone to Europe together in the early 1920’s and it was for his desire to marry her that my father initiated two or three attempts to break up his marriage to Helen Jenkins Masters. Mind you, I am not absolving him from blame in this, quite the contrary. For whatever reason, perhaps the angry rationale of an injured wife to blame her loss on youth, Ellen Coyne was targeted long after the fact. My mother had already graduated from the University of Chicago in 1921–1922 and left for New York City to pursue a career in the theatre while and during the divorce was in progress.

For Hardwick to say that “Masters moved to New York with his very young bride (note the qualification) and settled into the Chelsea Hotel, his wife going back and forth to teach in Pennsylvania” is totally false from beginning to end and in between. They had been introduced in Chicago. When he came to New York, they met again around 1924. They were married in 1926. I was born in 1928.

One interesting footnote to the divorce of 1922 which Hardwick’s research might have uncovered, is that Clarence Darrow represented Helen Jenkins Masters in her divorce suit. His advocacy came after the years spent with my father in a law partnership, as poker playing “buddies,” during which my father shared certain confidences with Darrow about his marital problems. I would guess he even shared details of his extramarital affairs as well. My father felt that Darrow’s punitive exercise of the case (which stripped him of all his possessions but the copyrights of his books which Darrow had asked the court for as well) was some kind of revenge on Darrow’s part for a slight or action that ELM could not understand. So, perhaps, this explains the silence on Darrow in the autobiography Across Spoon River, though he does refer to him under another name. On the other hand, recent research on my father’s papers suggests that about ten or twelve chapters are missing from the original manuscript of the book and that these had been removed, not published, for fear of a libel situation. Perhaps, they contain the reasons for the silence.

I’m grateful to your editors for this opportunity to correct these old lies and innuendoes which Elizabeth Hardwick has innocently refurbished. Ellen Coyne Masters, at ninety-two, is still very alert and hardy; however these mean slanders, ironically coming from the graves of vengeful minds long gone, are both painful to her and her family as well as being gratuitously silly.

Hilary Masters

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Elizabeth Hardwick replies:

In reply to Hilary Masters’s comments on my article about Vachel Lindsay, Edgar Lee Masters, and Carl Sandburg, I would like to make an apology to the son of Vachel Lindsay for having written that Lindsay had two children, both of them daughters. Lindsay had instead a daughter and a son to whom he gave his own name, Nicholas Vachel.

On the letter of Mr. Masters I would say, first, that the year 1869 is the date given in the Columbia Encyclopedia and in Webster’s Dictionary, but I accept his son’s assurance that Edgar Lee Masters was born in 1868. It does not appear to me that I made any slanderous remarks about the divorce of Masters and his first wife. I stressed that to me the marriage, as I could reconstruct it, was inexplicable given, as he himself said in his autobiography, the differences in their deepest attitudes on moral and intellectual matters. I also quoted his own desperate feelings about the marriage as it went on and said that naturally a divorce followed. On the matter of Ellen Coyne being thirty-three years younger, I did cite that twice and I agree that once would have been sufficient. The matter is only of anecdotal interest and even if it were the other way round it is not a gap that tells us much beyond the arithmetic of it.

The facts about Edgar Lee Masters’s condition when he collapsed at the Hotel Chelsea are still confused in my mind, but I accept Hilary Masters’s description of the facts and am sorry if they have been misrepresented by me.

I did not know that Clarence Darrow represented the first Mrs. Masters in what was obviously a bitter divorce and I can imagine that it explains the omission of Darrow in the Masters autobiography.

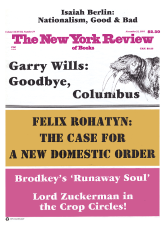

This Issue

November 21, 1991