In the 1970s I had lunch one memorable day with the French novelist Nathalie Sarraute. It was a year or two after Samuel Beckett had been awarded the Nobel Prize. I knew that Mme. Sarraute had known Beckett since before the war, and I brought up his name in the not very honorable hope of hearing some gossip about the great man. When I mentioned the prize, Mme. Sarraute said, Yes, in Paris we say he deserved it. Though her English is fluent, I assumed this somewhat peculiar phrase was a Gallicism, and I merely nodded solemnly in agreement. What I did not know, however, was that there had been a serious falling out between the two writers. Immediately, this kindly and most gentle of women flashed at me a sour look and with what for her was almost harshness said, No, we say: he deserved it.

Is the Nobel laurel wreath a fitting recognition of a great artist, or merely the international establishment’s way of turning a living writer into a monument? The prize committee has made some strange choices in the past, and there have been even stranger omissions: Joyce, Nabokov, Borges, Greene…. Of these four, Graham Greene would have seemed the most suitable candidate, since much of his work is set along that shifting boundary where literature and politics meet uneasily. The committee has always appeared distinctly chary of anything that smacks of art for art’s sake, preferring its literature well salted with political or social concerns; in this it is at one with most Western liberal intellectuals, who tend to have a bad conscience when it comes to literature—fiction especially—confusing as they do the ethical with the moral, expecting not works of art but handbooks on how to live.

If Nadine Gordimer had not existed she would have had to be invented. She is the ideal Nobel laureate for these times: an Olympian yet totally “committed” writer with ten novels and countless short stories to her credit; a white South African who has spent a lifetime fighting apartheid; a member of the ANC; and, as an added bonus, a woman. That the gentlemen in Stockholm, as Beckett restrainedly called them, should have waited until this year to give her the prize is a testament less to their acuity than to their caution. She should have had it years ago. She richly deserves it.

If there is a touch of Sarrauthian harshness here, it is because I have always had reservations about Nadine Gordimer’s work. There are some novels which are important but which have scant artistic value, and there are novels which are artistically successful and supremely unimportant, in the political sense. In the former category one thinks of 1984, in the latter, Lolita. Like all such distinctions, this one is clumsy, and much too dependent on personal taste to be of any real critical moment, and many great books (Mann’s Doctor Faustus, for instance) will elude its categorizations. All the same, it is handy. Nadine Gordimer’s books are undeniably important; not all of them are artistic successes.

Ms. Gordimer would probably dismiss such discriminations as quibbling. She has made the choice of commitment to a great cause, and this choice and this commitment constitute her artistic creed. Orwell himself observed that his decision to be a political writer, far from hindering him, brought him a sudden and almost blessed freedom: his program was set, his way clear, no longer would he spend his energies searching for the bon mot or the elegant aperçu. Ms. Gordimer is not so brisk as this; she can write with elegance and she makes fine discriminations, but at the same time wishes to eat the cake of commitment. This leads to some odd conjunctions. Here, for instance, from one of her earlier (1966) novels, The Late Bourgeois World, is a mother talking to her young son after she has broken to him the news of the suicide of his father. The boy ventures that “We’ve had a lot of trouble through politics, haven’t we,” and she replies:

“Well, we can’t really blame this on politics. I mean, Max suffered a lot for his political views, but I don’t suppose this—what he did now—is a direct result of something political. I mean—Max was in a mess, he somehow couldn’t deal with what happened to him, largely, yes, because of his political actions, but also because…in general, he wasn’t equal to the demands he…he took upon himself.” I added lamely, “As if you insisted on playing in the first team when you were only good enough—strong enough for the third.”

Even allowing that dialogue is not Ms. Gordimer’s strength as a novelist, this simply is bad writing. No mother would talk to a child like this; in life, perhaps, she might, but not in fiction. This is something Ms. Gordimer appears not to see, or at least to acknowledge: that truth to life is not always truth to art.

Advertisement

Directly after that little speech, however, comes this:

As he followed what I was saying his head moved slightly in the current from the adult world, the way I have sometimes noticed a plant do in a breath of air I couldn’t see.

It is a splendid recovery, as the polemicist, the journalist, steps back and allows the artist with her disinterested passion to take over.

There are moments, though, when even the artist’s touch fails. In “Some Are Born to Sweet Delight,” which is perhaps the weakest of the sixteen stories collected in Jump, an English working-class girl is taking the first, tentative steps toward an affair with her parents’ lodger, a young Arab:

She set him to cut the gingerbread:—Go on, try it, it’s my mother’s homemade.—She watched with an anxious smile, curiosity, while his beautiful teeth broke into its crumbling softness. He nodded, granting grave approval with a full mouth. She mimicked him, nodding and smiling; and, like a doe approaching a leaf, she took from his hand the fragrant slice with the semicircle marked by his teeth, and took a bite out of it.

This is a magical little moment, beautifully observed and rendered (despite the awkwardness of that “curiosity”); a few pages later, however, when the couple make love for the first time, the writer blunts the effect by repeating the image: “Now she had the lips from which, like a doe, she had taken a morsel touched with his saliva.”

Is this quibbling on my part? Well, a writer has only words out of which to make a world; the fiercest commitment, to the grandest of grand themes, is no guarantee of artistic success—and that is the kind of success Ms. Gordimer seeks when she sits down to work in the unique solitude of the writer. Too often in this collection she lets the words go dead on the page; too often she is content merely to state, as if what is stated (the grand theme?) will infuse the material with energy and light. Things—people, artifacts, ideas—are nothing in art until they are passed through the transfiguring fire of the imagination. Nabokov remarked that one of his difficulties in writing Lolita was that, after having spent his time up to then inventing Europe, he now had to invent America. Ms. Gordimer, in these stories at least, is too much the reporter and not enough of an inventor.

The story quoted from above shows her at her weakest. The girl falls in love with the young Arab, who makes her pregnant, and sends her off to visit his family, first placing in her handbag a bomb that will destroy the American airliner on which she is traveling, killing her and her unborn child and all the others aboard. We know nothing of the Arab, seeing him only through the girl’s eyes.

Then there was another disaster of the same nature, and a statement from a group with an apocalyptic name representing a faction of the world’s wronged, claiming the destruction of both planes in some complication of vengeance for holy wars, land annexations, invasions, imprisonment, cross-border raids, territorial disputes, bombings, sinkings, kidnappings no one outside the initiated could understand.

This is too easy. A piece of good, factual journalism on the same subject—such an incident happened a couple of years ago at Heathrow, though luckily the bomb was discovered before the young woman boarded the plane—tells us more about the issues and even the people involved, and probably would move us more, also.

There are three fine stories in Jump, and all three succeed precisely because the author insists on her authorial rights, as it were, and concentrates on the personal, on the predicament of human beings caught in a bad place at a bad time. “The Ultimate Safari,” in which a black girl describes a terrible journey from war to relative peace, fairly quivers with angry polemic, yet achieves an almost biblical force through the simplicity and specificity of the narrative voice.

We were tired, so tired. My first-born brother and the man had to lift our grandfather from stone to stone where we found places to cross the rivers. Our grandmother is strong but her feet were bleeding. We could not carry the basket on our heads any longer, we couldn’t carry anything except my little brother. We left our things under a bush. As long as our bodies get there, our grandmother said.

“Home” is a frightening study of the way in which a marriage between a Swedish scientist and the South African daughter of a politically active family is poisoned by the woman’s commitment to her mother and brothers when they are detained by the police. The husband, unable fully to identify with the fierce loyalties of the family, wonders if his wife has taken a lover; in the end, however, he recognizes the truth.

Advertisement

Perhaps there was no lover? He saw it was true that she had left him, but it was for them, that house, the dark family of which he was not a member, her country to which he did not belong.

The finest story here is “A Journey.” The narrator, a writer whom we are invited to identify as Ms. Gordimer herself, flying home to Africa from Europe, sits across the aisle from “a beautiful woman with a very small baby and a son of about thirteen” and makes up a life for them, involving love, infidelity, and the son’s first step across the threshold of adult-hood; it is a superb little piece, which could have been set anywhere, at any time: it is, in other words, universal. Here, as she does too seldom elsewhere in the collection, the author trusts her artistic energy, and makes up a plausible world. We can see the writer sitting in her plane seat, engaging in that pure and extraordinary form of play which is art. First the boy speaks:

I’m thirteen. I’d had my birthday when I went away with my mother to have the baby in Europe. There isn’t a good hospital in the country where my father is posted—he’s Economic Attaché=so we went back where my parents come from, the country he represents wherever we live.

The father, meanwhile, has come to the end of a love affair (it is a masterly piece of artistic tact that no details of this affair are given), and arrives at the airport buoyed up by the prospect of starting afresh the old life.

Through a glass screen he sees them near the baggage conveyor belt…. They are apart from the rest of the people, she is sitting on that huge overnight bag, he sees the angle of her knees, sideways, under the fall of a wide blue skirt. And the boy is kneeling in front of her, actually kneeling. His head is bent and her head is bent, they are gazing at something. Someone. On her lap, in the encircling curve of her bare arm. The baby. The baby’s at her breast. The baby’s there…. He doesn’t know how to deal with it. And in that moment the boy turns his face, his too beautiful face, and their gaze links.

Standing there, he throws his head back and gasps or laughs, and then pauses again before he will rush towards them, his wife, the baby, claim them…. But the boy is looking at him with the face of a man, and turns back to the woman as if she is his woman, and the baby his begetting.

It is an affecting, slightly eerie, and above all lifelike moment; it is all the more strong because there are so few such moments in this collection.

Ms. Gordimer has written a large number of short stories, but I think it is not really her medium. The form constricts her, she is not willing to obey its rules; she is inclined to be off-hand, to present us with bits of “life” like so many picked-up pieces, She needs the broader expanses of the novel, which afford sufficient room for her talent for leisured scrutiny of motive and action. Whatever her flaws as a writer, she has produced much powerful and moving work, especially in her more recent novels such as Burger’s Daughter and, her latest, My Son’s Story. Toward the close of the latter her narrator states for her the program which, as an activist and as a writer, she has followed since the start of her career, which is to make plain for the rest of us “what it really was like to live a life determined by the struggle to be free, as desert dwellers’ days are determined by the struggle against thirst and those of dwellers amid snow and ice by the struggle against the numbing of cold.”

Ian Buruma’s novel is also partly about race, though in a restrained, almost etiolated way. It is a fictional biography of Sir Ranjitsinhji Vibraji, Maharaja Jam Saheb of Nawanagar, an Indian aristocrat who at the turn of the century was one of the finest cricket players in the world, a genius on the field: in the 1899 season, for instance, he scored an astonishing total of 3,000 runs. Ranji, as he was popularly known, was born in 1872, and at the age of seven was adopted as his heir by the jam saheo of Nawanagar, whose natural son had come to what is termed “rather a sticky end.” Ranji, also under threat from conspirators, was first sent to an English boarding school in India, and later was brought to England, where he studied at Cambridge and molded himself into the very picture of a proper English gentleman, becoming in the process—almost incidentally, in Buruma’s version—a superb cricketer. In 1907 he became maharaja, and was, according to the history books, a progressive ruler. He served as a British staff officer in France during the First World War, and in 1920 was appointed the Indian states’ representative to the League of Nations. He died in 1933.

Playing the Game is an intricate but curiously muted book. It takes the form of a quest, by an unnamed narrator, in search of the truth behind Ranji’s carefully crafted and highly polished mask. A long “letter” from Ranji to his English friend, the cricketer C.B. Fry, in which the ailing and embittered maharaja recounts his life story, takes up most of the narrative. This is an inelegant but effective device. Buruma has found a seemingly authentic tone of voice for Ranji; the language is simple, formal, and convincingly “Indian,” though the author scrupulously avoids any hint of caricature. Ranji emerges as a decent, sad figure who has lived his life according to a code of “Britishness” which in the end has let him down.

Ian Buruma was born in Holland, and studied Chinese literature and history there, and later did postgraduate studies in Japanese cinema in Tokyo. He is something of an expert on the Far East, and has written two books, one on Japanese culture, and a second, God’s Dust, an account of a journey through Asia along the “opium trail.” He now lives in London, where he was until recently foreign editor of The Spectator, a sort of ruffianly high-Tory current-affairs magazine. With such a background, no wonder Buruma is fascinated by Ranji.

On one level this book is an examination of the phenomenon of the English gentleman, a breed which, if it ever really existed, has almost died out now. I am fascinated to discover, on Buruma’s evidence, that Dutch youths in the early Sixties were fervently Anglophile, adopting even the habits of speech of their English counterparts. The image of Ranji’s friend C.B. Fry reminds Buruma

of one of those Chester Barrie ads for tweed suits that fascinated me as a child. They were like images in a dream then. I would leaf through back numbers of Punch magazine with a feeling almost of reverence, as my eye caressed the pictures of cavalry twill trousers, Jermyn Street shirts, Viyella, Oxford cloth, houndstooth, herringbone, Prince of Wales, three-button, double-breasted, club tie. And the models in these dreams: long legs, white moustaches, blond, tanned faces with a hint of a smile, denoting complete, effortless superiority. When, later on, I saw these images come to life, speaking hearty banalities, I was keenly disappointed.

As an Irishman, I know the feeling.

Throughout the narrator’s travels in search of the real Ranji he is aided, and sometimes slyly hindered, by various Indian acquaintances and contacts. Chief among these is Inder, the Cambridge-educated poet and dandy, who is given some of the best lines. In a discussion with the narrator on the English passion for biography, he states one of the main themes of the book:

The English, you see, think of life as a performance—an attitude one might expect in such a ritualised society. People act out the roles that go with their class—or, indeed, the class to which they aspire, which is even more theatrical. My dear, England is a huge piece of theater, a continuous performance that goes on day and night.

It is this continuous performance which Ranji, asthmatic, loveless, and lonely, enters with melancholy enthusiasm; he “plays the game” so convincingly—convincingly to him, that is—that he thinks of himself as a sort of honorary English gentleman, even if of a dusky variety, and sees his role as that of a protector of the imperial dream: “My getting on was not simply a matter of personal pride and gratification…but of a far higher purpose; nothing less, indeed, than the future of our great Empire.” Bitter disappointment awaits him, of course; he takes the throne as the Raj is coming to a close, and ends his days immured in his palace with his pet parrot, thwarted by bureaucrats sent out by the Colonial Office to see that his lavish spending is curbed.

Playing the Game is one of those novels that flow through the mind cool and savorless as water yet leave behind a tenacious silt. Certain scenes in it, certain notions, even, will stay with me for a long time. The portrait of Ranji, with its melancholy and its sly suggestiveness, tells us more about imperialism than would a shelf full of political histories. There are splendid set pieces, in particular Ranji’s account of the fancy-dress cricket match arranged for the amusement of the Maharaja of Patiala by the egregious Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scout movement. The cricketers are dressed as women, their gowns designed and sewn by the finest dressmakers from Lahore. For the sake of diplomacy the maharaja’s team is allowed to win.

His Highness, with an undefeated twelve runs to his illustrious name, was cheered all the way to the pavilion. Elated by his triumph, he ordered Mr De Silva’s band to strike up a tune, and the waiters to uncork the champagne. “Dance, chaps, dance!” he cried, delighted with all the fun, and soon the cricket field was transformed into a great, green ball-room, filled with men in swirling gowns and gorgeous dresses, splotched here and there with patches of grassy mud, dancing in the beautiful Himalayan sunset.

Michael Ignatieff is a Canadian of Russian ancestry, a historian and journalist now based in London, where he is a cultural and political columnist on the Sunday Observer. He makes frequent appearances on British television as an anchorman on latenight shows, interviewing such heavy-weights as George Steiner and Susan Sontag. Considering all this, one would have expected his first novel to be a slim, stern, postmodernist exercise, set in a nameless state, with characters identified only by initials, engaging in gnomic exchanges about the nature of identity. Instead, Asya is a rather old-fashioned and unexpectedly suspenseful story, the kind of thing that publishers used to describe as a saga.

At the center of the book is Princess Anastasia Vladimirova Galitzine, born at the family’s estate at Marino, “a three-hour journey due west” of Moscow, on December 19, 1899.

Her mother, an Ourousoff by birth, was shy, pious and practical, while she was exuberant, godless and unworldly. True, she had inherited her mother’s tall, thin good looks. “You look like a fine pair of Borzoi hounds,” Father used to say to them in his jocular manner, meaning that they were fine-boned and delicate of feature, with long, finely tuned limbs. But there were other features that could not be traced to any pictures in the family album. She had curly black hair, pale white skin and lustrous black eyelashes. Her father said her most beautiful features were her firm, strong chin, indicating determination and character, her wide downy upper lip and her moth-grey eyes. But again, where did these features come from? “If I were not perfectly sure to the contrary,” her father often said to himself, “I would think she was not my child.”

The book opens with what we are to take as a significant scene: Asya as a child slips away from the house at dead of night and ventures out on to the frozen river.

She stood still and listened…. Blades scything, blades hissing, coming closer. Where had she heard that sound before? Then she knew it. It was a skater…. The veil of mist burst apart, the vast white figure hurtled past her and the ice beneath her feet gave way.

There is a long journey ahead of us before “the great skater” returns, but return he does, as we knew he would.

Revolution comes, then civil war, and Asya enrolls as a nurse. She meets the love of her life, a White officer. “There, on the footplate, his face red with the glow from the open hearth of the boiler, stood Sergei, a revolver in his hand.” After a brief and passionate affair they part, Asya flees to Paris, carrying Sergei’s unborn child. Years later Sergei turns up again, and becomes a businessman, dealing with the hated Soviets. The Twenties. The Thirties. War again. Sergei goes off to fight for the Poles. Asya is now in London, working for the BBC foreign service. She finds a new lover, Captain Nick Isvolsky, a former neighbor in the old country, but her heart still belongs to Sergei. The Fifties. The Nineties, suddenly. Asya returns to Russia, still searching for Sergei. There are Amazing Revelations (“Because I am his son”!) and, at the end, an ambiguous meeting in a cemetery. Blades scything, blades hissing….

Although a reader would have to have a heart of stone not to laugh at all this, the novel is nevertheless wonderfully entertaining, and at times quite moving. There is a sort of shameless enthusiasm in the plotting and the style (“He looked down into his drink. ‘Why am I telling you all this?’ “) which is irresistible. Throughout, one has an eerie sense of having been here before. The account of a Russian childhood recalls Speak, Memory, even down to the foreign names and the Anglophilia; later on we move into Ada territory (nude bathing, while brother Lapin, an Oxford man, waits with the towel); and that locomotive from the footplate of which Sergei waves his revolver, didn’t we last see that splendid machine pulling out of the pages of Doctor Zhivago? Twenties Paris (very well described, by the way) seems to derive from Scott Fitzgerald, with a restrained dash of Henry Miller; even Hemingway gets a nod: “She took his arm. ‘Remember, in Aigues Mortes, in that hotel room, with the terrible stained wallpaper, remember?’ ” It is hard to decide whether all this signifies merely that Mr. Ignatieff is easily influenced, or that he has written a dashing work emblematic of our hectic century. It hardly matters. It is charming.

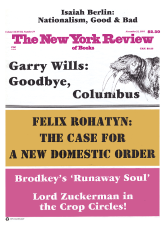

This Issue

November 21, 1991