The following speech was given on October 26, when President Havel received an honorary degree at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

It is a great pleasure for me to receive an honorary doctorate in a town in which many of my countrymen took refuge centuries ago, and which is still the domicile of many Czechs and Slovaks who have found a new home here while retaining close ties, in their minds, to their former country. Their old home is now at a historical crossroads: it is not only seeking a new form of statehood but, having freed itself from its position as a satellite, it is looking for a new political home both in Europe and globally as well. These two circumstances have led me to share with you some thoughts I wrote down recently on the subject of home.

The category of home belongs to what modern philosophers call the “natural world.” (The Czech philosopher Jan Patocka analyzed this notion before the Second World War.) For everyone, home is a basic existential experience. What a person perceives as his home (in the philosophical sense of the word) can be compared to a set of concentric circles, with his “I” at the center. My home is the room I live in for a time, the room I’ve grown accustomed to, and which, in a manner of speaking, I have covered with my own invisible lining. I recall, for instance, that even my prison cell was, in a sense, my home, and I felt very put out whenever I was suddenly required to move to another. The new cell may have been exactly the same as the old one, perhaps even better, but I always experienced it as alien and unfriendly. I felt uprooted and surrounded by strangeness, and it would take me some time to get used to it, to stop missing the previous cell, to make myself at home.

My home is the house I live in, the village or town where I was born or where I spend most of my time. My home is my family, the world of my friends, the social and intellectual milieu in which I live, my profession, my company, my work place. My home, obviously, is also the country I live in, the language I speak, and the intellectual and spiritual climate of my country expressed in the language spoken there. The Czech language, the Czech way of perceiving the world, Czech historical experience, the Czech modes of courage and cowardice, Czech humor—all of these are inseparable from that circle of my home. My home is therefore my Czechness, my nationality, and I see no reason at all why I shouldn’t embrace it, since it is as essential a part of me as, for instance, my masculinity, another aspect of my home. My home, of course, is not only my Czechness, it is also my Czechoslovakness, which means my citizenship. Ultimately, my home is Europe and my Europeanness and—finally—it is this planet and its present civilization and, understandably, the whole world. But that is not all: my home is also my education, my upbringing, my habits, the social milieu I live in and claim as my own. And if I belonged to a political party, that would indisputably be my home as well.

I think that every circle, every aspect of the human home, has to be given its due. It makes no sense to deny or forcibly exclude any one aspect for the sake of another; none should be regarded as less important or inferior. They are part of our natural world, and a properly organized society has to respect them all and give them all the chance to attain fulfillment. This is the only way that room can be made for people to realize themselves freely as human beings, to exercise their identity. All the circles of our home, indeed our whole natural world, are an inseparable part of us, and a medium of our human identity. Completely deprived of all the aspects of his home, man would be deprived of himself, of his humanity.

I am in favor of a political system based on the citizen, and recognizing all his fundamental civil and human rights in their universal validity, and equally applied: that is, no member of a single race, a single nation, a single sex, or a single religion may be endowed with basic rights that are any different from anyone else’s. In other words, I am in favor of what is called a civic society.

Today this civic principle is sometimes presented as if it stood in opposition to the principle of national affiliation, creating the impression that it ignores or suppresses the aspect of our home represented by our nationality. This is a crude misunderstanding of that principle. On the contrary, I support the civic principle because it represents the best way for individuals to realize themselves, to fulfill their identity in all the circles of their home, to enjoy everything that belongs to their natural world, not just some aspects of it. To establish a state on any other principle than the civic principle—on the principle of ideology, of nationality or religion for instance—means making one aspect of our home superior to all the others, and thus reduces us as people, reduces our natural world. And that hardly ever leads to anything good. Most wars and revolutions, for example, came about precisely because of this one dimensional conception of the state. A state based on citizenship, one that respects people and all aspects of their natural world, will be a basically peaceable and humane state.

Advertisement

I certainly do not want, therefore, to suppress the national dimension of a person’s identity, or to deny it, or refuse to acknowledge its legitimacy and its right to full self-realization. I merely reject the kind of political notions that attempt, in the name of nationality, to suppress other aspects of the human home, other aspects of humanity, and human rights. And it seems to me that a civic society, the kind that modern democratic states are gradually establishing, is precisely the kind of society that gives room to people right across the spectrum of what determines their nature—all those levels of the natural world that constitute their identity.

A civic society, based on the universality of human rights, best enables us to realize ourselves as everything we are—not only members of our nation, but members of our family, our community, our region, our church, our professional association, our political party, our country, our supra-national communities—and to be all of this because society treats us chiefly as members of the human race, that is, as people, as particular human beings whose individuality finds its primary, most natural and, at the same time, most universal expression in our status as citizens, in citizenship in the broadest and deepest sense of that word.

The sovereignty of the community, the region, the nation, the state—any higher sovereignty, in fact—makes sense only if it is derived from the one genuine sovereignty, that is, from human sovereignty, which finds its political expression in civic sovereignty.

Czechoslovakia is now faced with the task of building again, after more than forty years of totalitarian rule, the foundations of a civic society. Such foundations were laid in the United States of America over two hundred years ago, and civic society has been under construction in this country, without interruption, ever since.

It is clear in this situation who can learn more from whom: it is we who can learn from you. Next year has been proclaimed Education Year in Czechoslovakia, among other things because we will be celebrating the four hundredth anniversary of our own Jan Amos Komenský—Comenius—the great teacher of nations.

I would like to end with a request—the request that you, American scholars, come to our country as often as possible and teach us about civic society, about the kind of legislation and institutions it requires, and about what relationships should exist between these institutions and the citizens, and among the citizens themselves.

In short, I hope that you may come to teach us how to build a decent, humane home for all citizens.

Thank you.

—Translated from the Czech by Paul Wilson

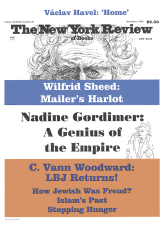

This Issue

December 5, 1991