1.

Haiti’s civilian leaders, including President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, have recently agreed to a plan for resolving the nation’s political crisis. But the Haitian army remains the key to the plan’s success. For as the army created that crisis late last September when it overthrew Aristide, the first freely elected president in Haiti’s history, so it will determine whether the artfully vague agreement put together in Washington on February 23 will succeed in ending it.

The army at least in size is hardly a formidable force. With only 7,000 troops, a handful of tanks, and antiquated systems of transport and communications, it is trying to keep the lid on an explosive population of six million desperately poor Haitians. So far, it has done so through sheer terror. According to Haitian human rights groups, since the coup the army has murdered 1,500 people, most of them presumed Aristide supporters or members of the popular movements that backed his presidency. Hundreds of others have been arrested and beaten, and the countless popular organizations, the trade unions and peasant and student groups, that had begun to appear in post-Duvalier Haiti have been silenced. Hundreds of thousands of Haitians suspected of being supporters of Aristide have been forced from their homes—most fleeing to Haiti’s mountainous interior, and thousands to a cool welcome in the Dominican Republic or by boat on the dangerous trip toward the United States. Not since the worst days of the Duvalier dictatorship has repression been so widespread and so brutal.

Yet the extent of the brutality also reflects the army’s dread of losing its precarious grip on power. One reason for the coup was the fear that Aristide was rallying his followers to avenge military abuses of the past. That fear has only deepened since the coup, and has been one of the main obstacles to Aristide’s return. “The army is condemned to violence,” Jean-Claude Bajeux, director of the Ecumenical Center for Human Rights and a leading social democrat, told me by telephone from Port-au-Prince. “The situation cannot last. You cannot rule a country with your finger on the trigger.”

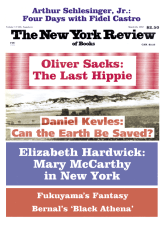

This Issue

March 26, 1992

-

1

See Haiti: The Aristide Government’s Human Rights Record, to which I contributed, by the human rights groups Americas Watch, the National Coalition for Haitian Refugees, and Caribbean Rights.

↩ -

2

Haiti: The Aristide Government’s Human Rights Record provides an accounting of these lynchings.

↩ -

3

Episodes of violence are detailed by Americas Watch, the National Coalition for Haitian Refugees, and Physicians for Human Rights in Return to the Darkest Days: Human Rights in Haiti Since the Coup.

↩