The familiar Honoré Daumier stirs our recall most frequently on the office walls where lawyers hang his savage portraits of their nineteenth-century counterparts in the serene and all-but-universal ignorance that severe strictures upon our colleagues could to any degree apply to ourselves. But there is also an unfamiliar Honoré Daumier, who might have raged contentedly on as journalism’s supreme caricaturist if he had not fallen out of fashion and been forced to become a great, if incompletely fulfilled, plastic artist. It is this Daumier that the Metropolitan Museum will be revealing to us in its current exhibition, which runs until May.

We can never think of him as other than an ironist; and he remains the cause of irony in others. As the best of stern republicans, Daumier hated power backed by weapons and wealth founded on paper and desired neither for himself. Naturally then, the House of Morgan is his exhibition’s patron and the Metropolitan’s Henry Kravis gallery is its lodgement.

It has been ever thus with Daumier. In the 1860s, Henry Walters, the American railroad enterpriser, commissioned him to paint the three classes of French train travel. Third Class evokes the endurance of the poor; Second Class is a prison cell for cankerings of envy for First Class, which belongs to gods and goddesses placidly indifferent to adventure’s pull.

Daumier’s affections are reserved for Third Class alone because it embodies patience, while Second is only jealous and First full of those dressed to be looked at and never to look. Boredom with train travel suffuses all three; and yet Henry Walters was as happy to buy the lot as a celebration of progress as lawyers are to spread out the preying creatures of the Palais de Justice as exemplars of their calling.

When Daumier the caricaturist lost his public, he tried his hand with private customers and even accepted religious subjects for commission to which he brought a surprisingly noble piety. His small drawing of the Madonna, the Child, and St. Anne is so wonderfully affecting as to remind us that, however republican and anticlerical a French manhood may grow, a Catholic boyhood remains. The huge drawing that Daumier called “The Riot” was probably inspired by the tumults of the 1848 revolution. And yet these naked bodies writhing in disorders of fear and anger call up the crowded canvases of Tintoretto’s crucifixions faithfully enough to include a fallen insurrectionist in the posture of a pietà. No other artist, not even Delacroix, has come so near conveying a civic uprising as a religious experience.

The longer he lived, the bitterer Daumier got about the injustices and chicaneries of the law. These are no longer caricatures but tragic incarnations. The condemned defendant faints at the verdict while his unmoved counsel fiddles with papers. The lawyer shrugs his shoulders at the beseechings of a client whose future already intimates itself in a head like a skull. A weeping woman in black makes her way to the exit while the swells of the bar parade unnoticing on their way to lunch.

In the end Daumier was all but forgotten except by the fellow artists whose admiration never diminished The lonely autobiographical note becomes stronger and stronger at the last. His street clowns beat their drums louder and louder, while unlistening crowds hurry to gaudier shows just as they had from him.

His final turn was to Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, those twin halves of his own nature. When he was nearly blind, he brought off a final Don whose outlines are almost lost in the white strokes of a Rosinante, suddenly transformed into a true steed of war. Their past like his is lost, their present like his is shadowed, and like him they rush boldly toward a future when his drawing will be seen to anticipate Toulouse-Lautrec’s and his use of light Monet’s, and where he, the Don, Sancho, and Rosinante will never grow old.

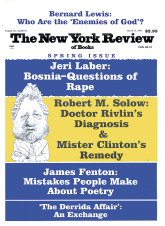

This Issue

March 25, 1993