Not only are the rich getting richer, but there are more of them around. In 1978, the Internal Revenue Service received 8,964 returns declaring adjusted gross incomes of more than $1 million in today’s dollars. In 1990, its most recent report, it counted 60,667 returns at that level.

More people are also poorer. Since 1978, the proportion of households falling below the poverty line has grown by 26.4 percent. Among families with children, the increase has been 38.3 percent. And there are fewer Americans in the middle. Since 1978, the proportion of families making between $25,000 and $75,000, computed in constant dollars, has dropped from 58.4 percent to 53.9 percent. The latter figure would have fallen even further were not more households relying on two earners.

Figures like these fill the pages of Boiling Point, in which Kevin Phillips describes at length the anger of millions of Americans over their loss of income and status during the last dozen years. Having given generous margins to Ronald Reagan and George Bush, Kevin Phillips tells us, they now see themselves as having been betrayed by “an elitist philosophy that celebrated investors, entrepreneurs, and the rich while neglecting the interests of a middle class that found itself increasingly threatened.”

Some of Phillips’s findings are especially revealing. For example, more than half of the additional income generated between 1977 and 1989 went to the top 1 percent of America’s households. In 1980, the compensation of corporate chairmen averaged thirty-five times that of a typical worker. By 1990, average pay and perquisites of the CEOs were 135 times higher. In 1950, a thirty-year-old man with an average salary could expect a paycheck 58 percent higher ten years later. In 1977, he would see his pay rise by only 21 percent during the next decade. Moreover, in 1990, almost a quarter of the unemployment claims filed in Massachusetts came from college-educated workers; and more than half of Arizona’s new welfare recipients had never before applied for such assistance.

For a quarter of a century, Kevin Phillips has identified himself as having special insights into the popular mind. As a consultant, he is much attended to by many in political and corporate circles who often feel otherwise remote from the opinions and passions of ordinary Americans. Thus Phillips intersperses his statistics with allusions to “voters from the small-town South, blue-collar Peoria, Levittown or the ends of Northern urban subway lines,” whom he characterizes as the “children and grandchildren of Alabama sharecroppers, Montana copper miners, Boston Irish policemen and Hungarian-American steel-workers in Pittsburgh.” Nor is Phillips simply a detached analyst of an aggrieved public. His tone makes clear that he wants to speak as their tribune and articulate deep “middle-class frustration” and “fear of downward mobility.”

But should the ideology and policies of the Reagan-Bush years be called a “betrayal”? After all, in three successive elections those men and their policies won significant victories. And vital to their majorities were the very voters who, in Phillips’s phrase, are now “boiling” over. Indeed, Phillips himself had something to do with the creation of the new conservative coalition.

In 1968, Richard Nixon won the presidency with 43.5 percent of the vote, the smallest such plurality since 1912. Despite that showing, Kevin Phillips, then a young lawyer working with Attorney General John Mitchell, felt no need to revise a book he was completing, which he entitled The Emerging Republican Majority.1 The 1968 contest had been a three-way race, with George Wallace winning five southern states and 13.6 percent of the national vote. Phillips’s advice to Nixon—to whom he dedicated his book—was to plan ahead for 1972 by making a home for the Democrats who had been attracted by Wallace’s segregationist message. Nor was this simply a “southern strategy.” Phillips’s reading of the returns showed that the Georgia governor had done well among white voters in the North and West, who were “in motion between a Democratic past and a Republican future.”2

More specifically, Phillips found that many blue-collar and middleclass whites had become disaffected by the attention the Democratic Party of Lyndon Johnson and George McGovern had been giving to blacks’ claims for equal treatment and recognition. “Negro-Democratic mutual identification,” he wrote, “was a major source of Democratic loss.” For a new Republican majority to form, he went on, its best bet would be to play on white resentment toward “Negro demands.” By encouraging “ethnic polarization” and aligning itself with the white side, Phillips prophesied, “the GOP can build a winning coalition without Negro votes.”3 In view of the growth of the Sun Belt and the suburbs, he told Garry Wills, “we don’t need the big cities, we don’t even want them.” The “whole secret of politics,” he said, is “knowing who hates who.”4 If would not be a great exaggeration to say that the young Kevin Phillips helped prepare the way for the use of Willie Horton in the 1988 campaign.

Advertisement

By all outward indications, the strategy worked. As Table A shows (see below), Nixon’s 1972 percentage exceeded his and Wallace’s combined showings four years earlier.

While the Watergate debacle made Carter’s victory possible, it gave the GOP four years to come up with a candidate who could give the party a populist energy. Playing the racial card remained part of the plan, as did rallying the religious right on moral issues. But Ronald Reagan embodied a nationalism that transcended party loyalties, one that pitted American purity against an Evil Empire. The voters who came to be called “Reagan Democrats” were those Phillips had identified in his 1969 book.

But it seems ingenuous to claim that these voters could have been oblivious to the favoritism that the Republicans were extending to the rich. When Phillips spoke of the Sun Belt, he had in mind not only the modest suburbs of San Diego and Dallas, but also the new fortunes being made in oil and savings and loan institutions. Nor can it be said that, until the recent recession, members of this new Republican majority objected to the preferment accorded to the aerospace industry and the profitable investments of medical doctors. If they wanted—and got—a party dedicated to “family values and white supremacy, they knew that others at the GOP table were more interested in corporate profits and amassing personal wealth. So it is not clear that they were “betrayed.” In 1992, however, some of the Reagan Democrats were afraid the extra recession would continue if Bush stayed in office.

The figures in Table B partly bear out Phillips’s thesis.

In the recent election, George Bush lost support at all levels, including among college graduates and those making more than $75,000. But he retained his majority among white voters. Had the balloting been confined to a white electorate, he would now be presiding as a plurality president. (Post-election polls found Perot’s supporters divided almost evenly on their second choice: 38 percent for Clinton and 37 percent for Bush. Most of the rest said that if Perot had not been on the ballot, they would have stayed at home.)

Phillips is not ready to say that the voters Clinton won over will provide a lasting Democratic majority in presidential elections. If they changed chiefly for economic reasons, will they return to their Republican ways when things get better? The “Negro-Democratic mutual identification,” which Phillips pointed to in the late 1960s, continues to characterize the party and is now joined by a similar linkage to homosexuality. The lesson of the last quarter-century has been that only a bleak economy can defuse emotion-laden issues involving racial conflict, welfare, and sexual behavior. Yet in the current situation, an emphasis on economic policy means more than winding down the recession, or even reducing the budget. Ironically, what may give Clinton a second term, and ensure a Democratic majority, will be a growing realization that for all classes of Americans, a relatively high rate of unemployment will be a chronic condition.

In citing the causes of the recent redistribution of wealth and income, Phillips estimates that “willful governmental action—direct and indirect—probably accounted for 30 to 50 percent of this upward shift.” Along with others who make their careers in or around Washington, Phillips is apt to overstress the impact of public policies. Thus he devotes entire chapters to the incentives and disincentives that flow from the federal regulation of interest rates and from tax breaks, the cost of bailouts of corporations and S&Ls by the government, and overt and covert subsidies. Unfortunately, Boiling Point has little to say about decisions and developments for which the government is not responsible. Indeed, Phillips’s own figures allow that anywhere from 50 to 70 percent of the movement of money to the upper-income groups can be attributed to changes within the private sector. One example has been the propensity of executives to take more from corporate revenues to fatten their own paychecks. At the same time, unions have been beaten back, payrolls and benefits have been slashed, and plants have been closed by shifting production overseas.

Employers have also been in large part responsible for changing the balance between men and women within their work forces, another cause of the changing distribution of income. Among full-time workers in 1971, there were 435 women for every 1,000 men. By 1991, the ratio had risen to 677 for each 1,000 men. More than that, the wages paid to men have declined, or at best barely budged. Since 1971, their median earnings in full-time jobs, in current dollars, inched from $29,702 down to $29,421. During those two decades, women’s earnings increased from $17,674 to $20,553.5 If employers are giving women jobs that were once reserved for men, the reason is not necessarily governmental prodding. While their wages have risen, the fact remains that women are often being taken on because they will work for less money. Indeed, in aggregate terms, the advances made by women have actually undercut the total amount of income going to working people.

Advertisement

Between 1970 and 1991, moreover, the proportion of families headed by single mothers more than doubled, rising from 9.9 percent to 21.1 percent.6 Despite gains in women’s wages, most of the single mothers who work hold low-paying jobs or live on public assistance, which in even the most generous states remains below the poverty line. The growing number of such households brings down the average figure for family income. Another “social” cause of the change in income distribution has been the decision to postpone marriage. Today, 18.8 percent of women who reach thirty are still unmarried, as are 29.4 percent of the men. Two decades ago, the respective percentages were 6.2 percent and 9.4 percent.7 While some of these unmarried adults share quarters with one other person, most do not. Because single-person domiciles have only one wage earner, an increasing number of them serve to pull down the average income figure for households as a whole.

In the past, many more Americans spent all of their lives within traditional families. Two married people who live together require less overhead than do divorced spouses living on their own. The same principle applies to children who stay under the family roof until they get married. While the new arrangements are becoming socially acceptable, we have been less willing to acknowledge that they are considerably more expensive. And since incomes have not been rising to meet these added costs, the result has been a fall in living standards, not only among the poor but also the middle class. It is not surprising that fewer economic complaints are heard from fundamentalist families, where parents remain together and children marry earlier.

High expectations for changing the economy have been raised for the new administration. When an opposition party takes power, it tends to promise sweeping changes and to be more responsive to the public’s complaints. As it happens, recent surveys have shown strong support for the President’s economic proposals, which is significant when we consider that over half of the voters supported one of his opponents. According to one New York Times–CBS News Poll, two thirds of the people interviewed said they understand that they would pay higher taxes, but still regarded the plan as fair toward people like themselves.8

Nevertheless, they have reservations. While 70 percent would be willing to pay $100 more a year to reduce the deficit, only 15 percent would be willing if the amount rises to $500. Half also oppose a serious increase in energy taxes, a reminder that most households own at least one car and have to heat single-family homes. Perhaps most revealing of all, 70 percent suspect that “the rich will figure out a way to get around” paying “the largest share of new taxes.” Still, the polls present evidence that, contrary to fears of politicans, Clinton has succeeded in showing that Americans do not adamantly believe that they need not pay a penny more for public purposes.

During its early months, the administration has given the highest priority to raising revenues to reduce the deficit. However, the Clinton campaign promised more than redressing the budget and ending the recession. It committed itself to restoring the nation’s economic growth, which would “create millions of high-wage jobs.”9

This was an unprecedented pledge. The jobs the New Deal created paid very low wages, but at that time they were eagerly accepted nonetheless. Today we hear less about public works, perhaps because today’s workers want the status and respect that go with private jobs. But creating new jobs will not be easy, especially when firms like Sears, General Motors, and IBM see slashing their payrolls as not simply a response to the current downturn but as long-term strategies. It remains to be seen if, during a period of economic recovery, firms can be induced to restore the relatively well-paid positions they have been eliminating, whether by replacing people with machines or removing middle managers or substituting lower-paid help both at home and abroad. It may well be that companies will no longer feel they need that many employees at, say, the $40,000 level. At one point even Phillips writes that too many production workers have been “over-paid.” Yet the seemingly high wage scales he refers to were important in creating the large middle class which is central to his analysis.

Some perspective may be gained by examining how the total amount of money that is used to pay Americans to work—what David Ricardo called the nation’s “wages fund”—is now distributed. In 1991, the most recent year for such figures, some $2.9 trillion in wages and salaries and fees was paid to the approximately 130 million men and women who worked at one time or another during the year. As Table C shows, the economy created 80.3 million full-time, year-round jobs, which represented 61.6 percent of the overall work force, and absorbed 82.1 percent of the earnings fund.

This left 17.9 percent of all earnings for the 50.1 million workers who held part-time jobs or worked less than the full year. While some of these men and women may only have wanted partial employment, we know that many would have preferred steady work, but were unable to obtain it because the economy was paying so much of total wages to those already in place. Indeed, there is a growing class of “contingent” workers, who are hired on a temporary basis at lower rates and without benefits.

Of course, many people with year-round jobs are poorly paid. Even so, some 10.7 million Americans had earnings of $50,000 or more, and 1.6 million were paid over $100,000 a year. Some $50,000 jobs are already being cut back: unionized airline pilots, for example, or professors who will be replaced by part-time “adjunct” lecturers. But as Kevin Phillips argues, things are getting better at the top, since persons earning more than $100,000 have not only grown in numbers, but have managed to commandeer a greater share of the money available as earnings.

The test will be how far our kind of government can strengthen the nation’s economic base so as to create more wealth and more decently paid jobs. If this is to happen, many patterns of behavior will have to be changed, whether through public incentives or other means. We hardly need reminding that Americans favor spending over saving, while those who do invest look more for paper profits than long-term capital formation. Or, to cite another aspect of investment, many Americans seem reluctant to press their children to apply themselves to difficult subjects at school. No doubt, most people will reply that they “work hard,” indeed that they have less leisure time than ever. Yet exertion in and of itself will not augment the nation’s product, especially when so much of what we call work consists of conversing and conferring and consulting with one another.

So the issue is whether the US can create the wealth it will need to produce Clinton’s well-paid jobs and restore Kevin Phillips’s middle class. If America’s middle class is shrinking, that same class has been growing throughout Europe and Asia and much of Latin America. If countries in those regions are supplanting us, it is because they are outmatching us in discipline and skills, indeed in showing that they are more efficient and imaginative at providing what the world wants.

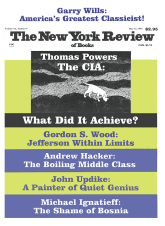

This Issue

May 13, 1993

-

1

Arlington House, 1969.

↩ -

2

The Emerging Republican Majority, p. 463.

↩ -

3

The Emerging Republican Majority, pp. 468, 470.

↩ -

4

Nixon Agonistes (Houghton Mifflin, 1970), p. 265.

↩ -

5

Bureau of the Census, Money Income of Household, Families, and Persons in the United States, P–60, No. 180, Table B–16.

↩ -

6

Bureau of the Census, Household and Family Characteristics, P–20, No. 458, Table A.

↩ -

7

Bureau of the Census, Marital Status and Living Arrangements, P–20, No. 468, Table C.

↩ -

8

CBS News Poll, February 20–21, 1993. The percentages cited are based on those having an opinion.

↩ -

9

Bill Clinton and Al Gore, Putting People First (Times Books, 1992), p. 3.

↩