1.

You have to go London to see the work of William Hogarth, but once there you ought to be able to take in most of his major paintings in a single day, on foot, starting from the Thomas Coram Foundation (the Foundling Hospital), and moving on to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, the Sir John Soane Museum, the Tate, and the National Gallery. A second day spent at the British Museum with his prints, followed by a sentimental spin out to Hogarth’s house in Chiswick, and you’ve seen the best of him.

No other British artist so completely identified himself with the city of his birth. Like Dickens, Hogarth celebrates the squalid spectacle of London life. During his rambles through the city his eye fell on prostitutes and parvenus, apprentices and aristocrats, the up and coming and the down and out. Much of the early Georgian city in his prints has disappeared, but the roiling under-class Hogarth depicted in print after print still exists—indeed it became much more visible after Mrs Thatcher became prime minister in 1979.

On a bad day London can still seem all too Hogarthian, a violent place, a filthy city where public drunkenness and extreme poverty are part of the teeming life in the streets. Rich and poor live noisily together in a relatively compact city center, so that the claustrophobia Hogarth emphasizes also feels familiar. A dozen newspapers keep everyone in touch with what everyone else is doing and thinking. Because the court, Parliament, and stock exchange are all here, satire spreads almost as fast as gossip. The eighteenth century had Hogarth, then Gilary and Rowlandson; today people read the satirical magazine Private Eye and watch the Hogarthian puppet show Spitting Image. Whenever tabloid headlines broadcast yet another episode in the marital saga of the Prince and Princess of Wales I think of the arranged marriage of the young Earl and Countess in Marriage A-la-mode.

Born in Bartholomew Close, near to both the medieval hospital of St. Bartholomew and Smithfield Market, Hogarth was the only son of one of those dreamy, feckless fathers such as belonged to Dickens and Thomas Lawrence, men whose failure in the race for success only served to steel their children’s determination to find security through popular acclaim. A Latin scholar from the North of England, Richard Hogarth established a London coffeehouse specializing in Latin conversation; this landed him, bankrupt, in the Fleet prison, where he was confined “within the rules” from 1708 to 1712.

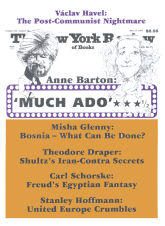

This Issue

May 27, 1993