A hundred and twenty-six years after its publication, Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women is a smash hit again. The new film version is setting records (mainly, as one might expect, among women of various sizes); the book is doing well. The new paperback “novelization” of the film, which is even briefer and more banal than one might expect, has already sold nearly 300,000 copies. And at Orchard House, the Alcott homestead in Concord, Massachusetts, mobs of tourists have created what are described as chaotic conditions.

In some quarters Little Women is also being welcomed for its support of what are called “Christian family values.” After all, it is the story of a united and affectionate family living in a small New England town that has become part of the American myth. It features kind, wise, and loving parents, always ready with a warm hug and a moral lesson, and four charming teen-age daughters who have never heard of punk rock or crack cocaine. Moreover, the book is American history as well as myth: it is based on Alcott’s own childhood and adolescence.

One era’s conservatism, however, may be the liberal protest of an earlier time. When it appeared in 1869, Little Women was in many ways a radical manifesto. Its author was an independent, self-supporting single woman in an age when, as Meg puts it in the book, “men have to work and women to marry for money.” Louisa May Alcott was also a committed feminist who wrote and spoke in favor of women’s rights. In 1868, while she was creating Little Women, she joined the New England Woman Suffrage Association.

Alcott came by her radicalism naturally. She was the daughter of what would now be described as vegetarian hippie intellectuals with fringe religious and social beliefs, and spent nearly a year of her childhood in an unsuccessful commune. Her most famous book, Little Women, was equally radical in its time. Its central character, Jo March, has almost nothing in common with the self-sacrificing heroines of the best-selling girls’ books of the day—books like Charlotte Yonge’s The Daisy Chain (1856) and Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World (1851), both of which Jo reads in the course of the novel.

Developments in intellectual and social history, and even in human biology, have greatly altered the impact of Little Women. The unaffected asexual innocence of the four teen-age March sisters, for instance, now seems almost unbelievable. In fact it would be inconceivable today, but not in 1868. Louisa May Alcott wasn’t portraying herself and her sisters as unnaturally immature, but as typical adolescents of a time when most women did not reach puberty until their late teens. In England, where the best records exist, the median age of menarche (first menstruation) in the 1830s was 17.5; by the 1860s it had fallen only to 16.5, and by the 1890s to 15.5. (Today it is down to 12.5.)1 A young woman born in the 1830s (like Louisa May Alcott and her sisters) who married at sixteen or seventeen, as some did, might still be sexually immature at the time of the wedding.

Several explanations have been offered for this delay in maturation. The most common is that it was due to lack of exercise and deficiencies in women’s diet. In the early nineteenth century it was generally believed that middle-and upper-class women needed different food from men: more sugar and much less protein. The meals in Little Women emphasize sweets and carbohydrates: biscuits, pancakes, lemonade, gingerbread, pudding, fruit in season—and for a treat, ice cream, cake, and coffee. Meat and vegetables are hardly mentioned. Middle-class nineteenth-century women were also much less active than men, and the voluminous, constricting clothes they wore often made it difficult for them to exercise at all.

The typical early Victorian girl in fiction was almost totally innocent and without sexual drive. Her childlike modesty and timid tremulousness when approached by a likable suitor can be seen as instinctive rather than flirtatious; it might be compared to the reaction of a ten-year-old today to the teasing of boy playmates.

Part I of Little Women, though it is set in the years of the Civil War (1860–1864), was actually based on Louisa’s own adolescence during the late 1840s. When the book begins, Amy is twelve, Beth thirteen, Jo fifteen, and Meg sixteen; none of them appears erotically mature, though Meg is on the verge. They are uninterested in boys except as pals, and in no hurry to leave home. When a suitable young man falls in love with Meg, Jo calls this “a dreadful state of things” and exclaims “I just wish I could marry Meg myself, and keep her safe in the family.” The vehement childishness of this speech has puzzled some modern readers, and even led others to suspect an unnatural lesbian attachment, but at the time it would have been seen as a comically outspoken expression of family loyalty.

Advertisement

Radical though she was, to some extent Louisa May Alcott softened and altered her story to suit contemporary tastes. Her father, Bronson Alcott, was not, like Mr. March, a mild and kindly minister—he was a famous, and famously difficult, New England eccentric: unworldly, reserved, and emotionally unstable. Mr. Alcott, the self-educated friend of Emerson and Thoreau, allowed his wife, Abba, and later his daughters (especially Louisa) to support him while he traveled about lecturing in a high-flown but fuzzy manner on Transcendentalist philosophy and educational reform. For a while the family lived in a utopian community called Fruitlands, where Abba and the older girls did all the domestic work and served as farm laborers, while Mr. Alcott wrote high-minded accounts of the enterprise.

Bronson Alcott was not only a social but a religious radical. He was drawn to what at the time were extreme beliefs: he was an abolitionist, a vegetarian, and supported the Temperance Movement. His educational ideas, based on the writings of Rousseau, were far ahead of his time. The Temple School in Boston, which he founded, gradually lost students and closed after five years because parents objected to the admission of a black pupil and to lectures that denied the divinity of Christ. In Little Women Jo is familiar with the religious radicalism of her time and troubled by it: one thing her future husband, Professor Bhaer, does for her is to restore her faith:

Somehow, as he talked, the world got right again to Jo; the old beliefs, that had lasted so long, seemed better than the new; God was not a blind force, and immortality was not a pretty fable, but a blessed fact. She…wanted to clap her hands and thank him.

Louisa May Alcott solved the problem of her peculiar and unconventional father by largely removing him from Little Women. When Part I begins, Mr. March is working at an Army hospital in Washington, something Louisa herself (but not Bronson Alcott) actually did. He does not return until almost the last chapter. In Part II he is almost as absent: “a quiet, studious man,” who appears only now and then to make moral observations and criticize Jo’s money-making sensational tales, while accepting the comforts they earn.

Though Bronson Alcott was unable to attract many followers or make Fruitlands a success, his daughter gave his educational and social theories wide circulation in her books. But she presented these then very radical ideas with such skill and charm that most of her readers did not protest. In Little Women, for instance, the girls read the New Testament and model their lives on Pilgrim’s Progress, but do not go to church. Like the Alcott family, they never touch alcohol.

The Marches also practice charity in a hands-on way. Instead of with-drawing uneasily from the rush of German immigrants (thousands of whom flooded into America in the 1860s and 1870s), they take on the Hummel family and its seven children as a personal responsibility. Later, with the approval of her parents, Jo marries a middle-aged and penniless German with a strong accent. To understand this in contemporary terms, one must imagine the reaction of a New England WASP family whose twenty-five-year-old daughter has just announced her engagement to an unemployed Central American refugee in his forties, with two orphan nephews to support.

Alcott also conventionalized her mother and sisters to some degree. Abba Alcott, who once rebelled against her husband by walking out of his commune and taking her daughters with her, becomes Marmee, a model of the patient and dutiful wife. Meg, like Anna, becomes a housewife and the mother of twins; and Beth, like Elizabeth, dies young. But Jo and Amy (May) were given more romantic destinies than their originals. Amy marries Laurie when she is twenty-one and gives up art as a career because “talent isn’t genius.” In reality May Alcott did not marry until she was over forty, after many years as a professional artist. Louisa never married, but Jo gets an unconventional but likable husband who, as Sarah Elbert says in A Hunger for Home,2 “has all the qualities Bronson Alcott lacked: warmth, intimacy, and a tender capacity for expressing his-affection.” He also does the shopping and shares child-care.

From a mid-nineteenth-century perspective Little Women is both a conservative and a radical novel. Some aspects of it, and some characters, represent the past; others look to the future. Like much earlier juvenile literature, it is often sentimental, full of moral lessons, and centers on a selfcontained family unit which tends to exclude outsiders. The March girls, unlike teen-agers today, apparently have no best friends, and neither does Marmee. When Laurie appears, he is accepted as an adopted brother.

Advertisement

But in an age of patriarchal Victorian families, the Marches are a matriarchy. Mr. March is a background figure even when he is on the scene. It is Marmee to whom the girls go with their troubles, and it is she who comforts and advises them, and is the central force in the household, as is clear from the picture of the four girls grouped round her that appears in most editions—and in some current advertisements for the film.

In an innovation that was widely copied later, Louisa May Alcott replaced the single central character of the standard juvenile with four heroines, each with a different personality. Before Little Women, there was one ideal type of girlhood in most juvenile literature: modest, dutiful, and obedient. Now Alcott suggested that there was a range of possibilities, and that a heroine could have serious faults—vanity, jealousy, sloth, and anger—and still earn a happy ending. She thus made it easy for real young women to see themselves in the story.3 Moreover, through her four heroines she was able to represent and comment on four contemporary views of womanhood.

Beth is the typical early Victorian girl-child: sweet, shy, passive, and domestic—the traditional angel in the house. At thirteen she still plays with dolls. Her life is centered in the family, and her dearest wish for the future is “to stay at home safe with Father and Mother.” Unlike the other girls, she does not work outside the home, and seems almost never to leave it. Her death, like that of Dickens’s Little Nell and many other children in nineteenth-century popular fiction, suggests that innocence and virtue are innately fragile and fleeting, unable to survive in the real world. Historically speaking, she represents a view of womanhood that was literally passing away at the time. The hidden message to the reader is that to stay at home safe with your parents is to die.

Meg, on the other hand, is a woman of the mid-nineteenth century: an exemplar of what at the time was called the Domestic Movement. Little Women begins during the first winter of the Civil War, which removed men from the home and gave middle-class women like Marmee and her daughters more power and responsibility. After the war ended many writers encouraged women to keep what they had won: to take charge of their homes and children rather than cede control to servants and male authority. That this was in some sense a new idea is clear from the episode in which the four girls try living for a week without household help, and it turns out that none of them, not even Beth, knows how to cook—something that would be considered most peculiar today. By the end of the novel, Meg is fully in control of her domestic circumstances. If you want to marry and have children, the book suggests, make sure you are in charge of your own life.

Amy, the youngest Little Woman, appropriately embodies one of the newest developments in American society: the entry of women into the arts. She belongs to the generation of painters like Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) who went to Europe to study art just as their brothers had been doing for years. Amy’s talent is recognized early, and though she doesn’t become a professional artist, she continues to paint and sculpt, and there is no suggestion that her efforts are frivolous. Implicitly, her career suggests to the reader that if you wish “to be an artist and go to Rome,” it may happen.

After her marriage to Laurie, Amy travels in Europe and together with her husband brings back artistic treasures and helps struggling artists of both sexes. She thus also stands for the many well-to-do late-nineteenthcentury women like Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924), May Alcott’s near contemporary, who became important collectors and patrons of the arts.

Jo, of course, represents the feminist movement; in the phrase of the period, she is a New Woman, who chooses a career. Jo is also one of the first and most famous positive example in fiction of a new kind of girl: the tomboy. In chapter one of the book she declares, “I like boys’ games and work and manners! I can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy.” (She hates her given name of Josephine, and, as some readers have pointed out, has a nickname that might easily belong to a boy, while her friend Theodore Laurence is known by the girlish name of Laurie.) All through the book her parents and sisters and friends keep trying to suppress the boyish side of Jo, but they never totally succeed, and at the end she is still romping about, careless of her clothes, and talking boys’ slang, although she is married and a mother.

The career Alcott gives Jo in Little Women and its two sequels, Little Men (1871) and Jo’s Boys (1886), is well ahead of its time. In contemporary terms, she has it all: not only a husband and children but two careers; and she doesn’t have to do her own housework and cooking. She gets away with it partly because both her occupations are “women’s work”: running a progressive boarding school and writing for children. The message to the reader is clear: demand freedom and independence, and you may get it—and love as well.

Perhaps Jo also manages to have it all because she, like Louisa May Alcott, depreciates her literary efforts and excuses them as financially necessary. Even nearly twenty years later, in Jo’s Boys, she speaks of herself as a “literary nursery-maid who provides moral pap for the young.”

Louisa May Alcott, like many other women writers of her time, put her duty to help support her family above the demands of art, and felt herself under pressure to write as fast as possible. Of one of her best adult novels, Work (1872), she wrote, “Not what it should be—too many interruptions. Should like to do one book in peace and see if it wouldn’t be good.” But though in the end she was supplying her parents with a comfortable life and sending her sister to study in Europe, she never allowed herself to “do one book in peace.”

This sort of female self-destruction and self-denigration, perhaps undertaken originally out of lack of confidence, or to deflect criticism, was endemic in the late nineteenth century, and continued long into the twentieth. Possibly as a result, men gave up their exclusive rights to the production of “serious literature” very slowly. Even after they began to allow writing by females into what is now called the canon, they were enviously reluctant to admit that a woman could produce both good books and babies. For many years the serious lady writer had to be childless like Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot, and Virginia Woolf; it was even better if she were single, like Emily Brontë and Emily Dickinson. Gifted novelists and mothers such as Elizabeth Gaskell and Margaret Oliphant were seen as somehow unimportant and second-rate; often it was implied that their books would only interest other women.

Though she was a spinster, Louisa May Alcott’s attitude toward her work insured that for over a hundred years she was dismissed as merely a juvenile author; it was not until the 1980s that her work was taken seriously and her adult novels: Moods (1865), Behind a Mask (1866), Work (1873), A Modern Mephistopheles (1877), and A Whisper in the Dark (1888), were reread and reissued.4 Today she is a hot property. Her novel A Long Fatal Love Chase, considered too sensational for publication in her own time, has now been bought by Random House for 1.5 million dollars, and the actress Sharon Stone is said to be “practically obsessed” by the idea of starring in a film version.

Little Women has always attracted movie makers. The current film is the fifth (two silent versions have been lost), following those of 1933 and 1949. It is directed by an Australian, Gillian Armstrong (best known here for her lively My Brilliant Career). In many ways it is an outstanding success: the New England scenery looks real as well as picturesque, and the March family house is not ridiculously large. For the first time, the characters are not obviously wearing makeup, and their clothes appear actually to have been worn and washed and mended before they were photographed. There is even a strong family resemblance among the Little Women: Trini Alvarado as Meg, Winona Ryder as Jo, and Claire Danes as Beth really look like sisters, something that has never been true before.

In other ways, however, the demands of Hollywood seem to have won out over authenticity. It is easy to forgive the heightened drama of some of the scenes in the film: the invented moment when Laurie kisses the twelve-year-old Amy, and the suspense-filled last-minute meeting of Jo and Professor Bhaer. The glamorizing of the characters is harder to accept. As Caryn James has pointed out in The New York Times Book Review, in each film version Professor Bhaer has become younger and better-looking. In the book he is a stocky middle-aged man with thick glasses whom Jo loves in spite of his nondescript appearance: Paul Lukas, in 1933, more or less fit the part. In 1949 Rossano Brazzi was middle-aged but good-looking, and today Jo ends up with the romantically handsome Gabriel Byrne.

In all three films the Hollywood demand for stars has affected the casting. Alcott presents Jo as definitely plain: she is “tall, thin, and brown” and coltishly awkward at sixteen. In the 1933 version Katharine Hepburn was not only ten years older and absolutely wonderful-looking, but she obviously came from another and more aristocratic background than the rest of the family. June Allyson, who played Jo in 1949, was thirty-two and looked it. In the current version, Jo’s long, thick chestnut hair is described, as in the book, as her “one beauty,” a remark that makes no sense, since Wynona Ryder is one of today’s most striking young actresses.

When the book begins, Amy is twelve and in despair over her flat nose, which she tries to improve by wearing a clothespin on it. In the 1933 version she was played by Joan Bennett, who was not only very pretty but twenty-four and pregnant. In the 1949 Little Women Amy was the seventeen-year-old Elizabeth Taylor, probably the most perfectly beautiful teen-ager in America at that time. In the new film, at last, the younger Amy is a real child actress, Kirsten Dunst, in Part I.

The further we are from the nineteenth century, of course, the more Little Women becomes a period piece. The 1933 film could still present the Marches as an idealized version of the contemporary American family. Today they are clearly a vanished species, though attempts have been made to update the story for the 1990s. The gap Louisa May Alcott created between her own life and that of her characters, for instance, has been collapsed. Bits of Alcott biography and literary history have been shoehorned into the film: Jo asks Professor Bhaer if he knows what Transcendentalism is (he does, of course); and we are informed that Mr. March’s school, like Bronson Alcott’s, was closed after he admitted a black student. And Susan Sarandon (looking lovely but somewhat uncomfortable in a hoop skirt) now speaks on the importance of rights for women, and against slavery and the constrictions of the corset, expressing the radical opinions of Louisa May Alcott and her mother rather than those of the more pious and proper Marmee of the book.

As usual in movies set in the American past, Little Women is wonderful to look at, full of Currier and Ives New England landscapes, picturesque nineteenth-century costumes, horsedrawn carriages, log fires, and loving relatives gathered round a Christmas dinner table or dancing on the grass at a summer wedding. It is not surprising that reactionaries should see it as propaganda for family piety, reverence for established institutions, and the domestication of women. But under its old-fashioned disguise, the film of Little Women, like the book, recommends quite another set of values.

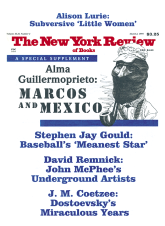

This Issue

March 2, 1995

-

1

See Joan Jacobs Brumberg, ” ‘Something Happens to Girls’: Menarche and the Emergence of the Modern American Hygienic Imperative,” Journal of the History of Sexuality (July 1993).

↩ -

2

Rutgers University Press, 1987, p. 210.

↩ -

3

It is not true, as often asserted, that everyone identifies with Jo. Though many do, an informal survey of several hundred students at Cornell over the past twenty years has turned up many who related most closely to Meg, Beth, or Amy.

↩ -

4

Louisa May Alcott, Unmasked: Collected Thrillers, edited by Madeline Stern, will be published by Northeastern University Press in May.

↩