Nothing is more important in Russia right now than to stop the war in Chechnya, to halt the killing and suffering.

When I visited Chechnya with colleagues from the Human Rights Commission, along with monitors from the Russian State Duma and the Memorial Society, we soon found that there was no way to make a direct count of the numbers of civilians who had been killed in the war. Even before the war started, General Dudayev’s government did not keep accurate records of Chechen deaths, and there is no question of anyone doing so now. During December and January the hospitals and Grozny’s city authorities simply had no time to keep records.

Still, we were able to question closely some 491 Chechen refugees (from 99 different families) about what happened to their relatives and friends. By extrapolating statistically from their experiences, after making allowances for accounts that overlapped, we were able to arrive at an estimate of the numbers of deaths in Grozny from November 25, 1994, to January 30, 1995. We concluded that about 25,000 civilians were killed as a direct consequence of the military attack on Grozny. Most of these were killed by indiscriminate bombing and artillery or mortar fire. They were, in effect, trapped victims, many of them ethnic Russians, who were caught in the path of the Russian attack.

On the basis of the same interviews, we estimate that among the 25,000 civilians who died in Grozny more than 3,000 were defenseless civilians deliberately killed by snipers or by commando units mopping up after the assault on the city. For the most part those who killed civilians in cold blood in this way were members of the special forces of the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Interior, not the regular army units which are made up largely of draftees.

For the period of the war after January 30, we have been unable to make similar statistical estimates of the numbers of people killed, but estimates made by others have run as high as 60,000 civilians and soldiers killed as a result of the war in Chechnya since November 25. There is no way to confirm this figure; but in view of our own conclusion that some 25,000 civilians were killed in Grozny alone during the first two months of the war, it does not seem implausible.

We were particularly concerned about the treatment of the Chechens who were detained and taken for questioning to temporary interrogation centers or to the main “screening centers” in Mozdok and in Grozny on grounds that they were in some way supporting the Chechen forces. The Russian government has been extremely evasive about these centers and has only rarely and reluctantly permitted carefully supervised visits to them by Russian deputies and foreign observers. If my memory is correct, official reports state that something like 580 persons have passed through the screening center in Mozdok, but I suspect that the number of Chechens who have been detained in the various preliminary screening centers runs into the thousands.

The government has good reason to be evasive about its interrogation centers. We took testimony from more than a hundred witnesses who had been held at the centers concerning what had happened to them and what they observed. Some asked that their names not be disclosed, but most of them gave us signed statements.

Many of them were first arrested on technical grounds, such as being vagrants or beggars, even though they were in their own apartments when they were picked up. One of the first things the Russians would do was to destroy their identity cards, ripping them up in front of their faces.

Virtually everyone who was detained was beaten and subjected to degrading treatment, and many were tortured. Some were subjected to electric shocks. Others were savaged by specially trained dogs. Still others had hoods put over their heads, and they then were nearly asphyxiated by carbon monoxide piped in from a car exhaust.

In many cases the interrogators demanded that the prisoners confess to giving help to General Dudayev’s forces. The prisoners were often brought in blindfolded and told to sign documents they could not see. There was no question of any regulations being observed concerning the proper treatment of prisoners. In most cases the Russian commanders have done nothing to stop the brutality. And on some occasions, we were told, they were present while abuses were going on, and even have encouraged them. What seems clear is that the Russian army is seeking to terrorize Chechen civilians to keep them from giving support to the Chechen fighters.

So far efforts to make peace from whatever quarter have been futile. Our own attempts began in December, when we made calls both to Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev and to President Dudayev proposing to explore the possibilities of a cease-fire and of initiating serious peace negotiations. It briefly seemed that something might come of this, but all such efforts were blocked by Russian military commanders in Chechnya or by officials in Moscow.

Advertisement

We undertook peace initiatives on at least four occasions, and other parties, including deputies from the Russian State Duma, have also engaged in peacemaking activities. The general idea has been to start with a cease-fire and arrive at a peace settlement by stages. The Chechen leaders expressed willingness to meet with the Russians to discuss these proposals, and they seemed ready to accept a cease-fire in place while peace talks got underway. The Russian responses, however, have usually been cast in the form of an ultimatum, requiring Chechen forces to unconditionally surrender their weapons before negotiations for a political settlement could begin. In my view, the Chechen forces would not accept such a surrender even if Dudayev ordered them to do so. They are by now too committed to resisting the Russian invaders and too fearful of what would happen to them if they gave up their arms. The Russian commanders have unilaterally declared several cease-fires, but these have been disingenuous concessions to domestic and foreign pressures, not the start of a genuine peace process.

Despite all these difficulties, I still hope that a cease-fire can be arranged and that, soon after one is in place, negotiations over Chechnya’s political future can begin between the Russian authorities and a Chechen delegation that has the genuine support of the Chechen people. After all the violence that has occurred, it will of course be extremely difficult to negotiate a durable peace settlement. But it must be done to halt the killing and prevent further suffering. The war must also be ended to stop President Yeltsin’s increasing estrangement from Russian democrats and the Russian government’s drift toward derzhavnost, a word perhaps best translated in English as “quasi-totalitarian statism.”

—May 11, 1995

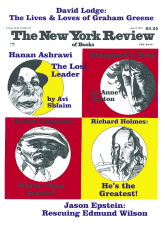

This Issue

June 8, 1995