1.

In St. Louis a warm wind had unexpectedly arrived to draw moisture from the cold ground and cover runways with layers of dense fog. The flight boards in LaGuardia said “Canceled” for Chicago, too. Detroit was socked in, Cleveland growing gray, so there’d be no back door through which I might return. I thought I was traveling light, but my briefcase was galley heavy and I heard my squashed socks moan; though perhaps it was static on the line I was hearing when I tried to phone for a room at one of the airport motels. A faint foreign voice believed they might have a suite for $220 if I hurried. None of the others answered.

Since the flight I’d been rebooked on (after languishing in line like a pin of forgotten wash) was scheduled to take off as a herald to the dawn, I thought returning to Manhattan for the night seemed silly—it had become a place as far away as Nome. Furthermore, I didn’t relish the idea of trying to capture a cab from a dim slick New York street at five AM. Already the mesh gates of some concourses were coming down with a coarse crash, denying me sleeping space on a length of their cool-a-heel seats. And dinner with any decency was done for. Even the plastically appointed eateries, squalors full of redundant light and fast food, were emptying their patrons into mournful halls; my fellow maroonees had gone to houses or hotels so promptly I never saw them leave; and I began to feel I had made a stubbornly stupid choice (to stick it out where I was), because there might be nothing to stick to: mops and pails, lowered lamps and jailhouse grills, would see to that.

For a while I wandered (heavier, though, than a lonely cloud), until I came upon The Bar—The Bar—which lay like a filled-in ditch alongside twenty-five yards of dismal glarelit passage constructed to connect these snoozy airlines with one another. The place served sloppy dogs and chili. With grateful haste, I seated myself at a small round table next to the alley’s imaginary edge where I might enjoy the baleful and incessant hall light, ordered the Blush, which was this pseudo-saloon’s so-called choice, extracted a ponderous galley from my case, and vowed to drink wine and read Musil the rest of the night.

Oddly enough, it proved to be the right time, the perfect place. Vienna. An evening in August 1913. The characters in Musil’s novel gather and disperse like strangers in an airport bar. First Ulrich, the man without qualities himself, the son of a provincial civil servant, who, we are told, has taken a year off from his mathematical studies in order to drift and observe. His passivity carries him from opulent drawing rooms in Vienna to a walled garden in a provincial town, puts him in odd situations, including a brief arrest for defending a drunk who has been loudly insulting the government.

The oddest of all is that he accepts the post of General Secretary to the “Parallel Campaign,” the bit of stupid nonsense that serves as the ironic center of Musil’s never less than serious novel. Observing the calendar with a political eye, the Prussians have decided to celebrate the thirtieth year of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s reign in 1918. In a customary fit of inferiority, desperate not to be outdone, and with a weightier, more redolent reason, the Austrians determine to surpass the Prussians by mounting the Parallel Campaign, a celebration of Emperor Franz Joseph’s seventieth jubilee in the same year.

Since it is a piece of patriotic and royalist propaganda, the Campaign, as it comes to be called, has to have a theme, a vision which should appear clear and vast. It must exhibit an idealism quite out of Prussia’s range. Perhaps the governing goal should be that of “human unity” (paradoxically, a hope that mimics Ulrich’s own desire for a scientific morality which would successfully wed thought and experience), a unity that Austria may be the first to manifest, since Austria is royalist and Catholic, not aggressively materialistic and expansionist, or coolly scientific and reductive, like the Prussians. Of course, in 1918, these parallel aristocracies, and all the bureaucrats who dangle from them like badly pinned medals, and the careful hypocrisies whose cultivation has been their business, will be torn and tarnished, rendered kaput, be brutally exposed, or put in deadly disarray. But those events lie in a future that Musil’s narrative will never reach.

The bar begins to fill with lost souls like me, students in a style one might call “German Youth,” wearing layers of fashionable rags, then a few commercial types in sober suits, and shortly after them, as I spread out my galleys, Musil’s moods and characters arrive, along with his ironic eye. Soon I am in the company not only of Ulrich but of the woman who has become the muse of the much-heralded Jubilee, the voluptuous and socially aspiring Diotima, her would-be paramour, the industrialist Dr. Paul Arnheim, and other characters as packed with reflective consciousness as overpopulated countries; and now another lonely man like me appears, his round table, like mine, spread with papers. Suddenly it’s ten PM. There will be no more liquor served or sold. Weak coffee in waxed cups. On paper plates, tacos smothered in pus and blood. I have reached Part II in my reading: “Pseudoreality Prevails.” Musil’s question has been: Has the moral and intellectual condition of man been getting better or has it been getting worse? Oh yes, and another subject concerns the early pages: the nature, the infrequency, the futility of being a genius.

Advertisement

The Man Without Qualities: What is his opinion? Well, Ulrich thinks, things within Austria are certainly improving. After all,

Men who once merely headed minor sects have become aged celebrities; publishers and art dealers have become rich; new movements are constantly being started; everybody attends both the academic and the avant-garde shows, and even the avant-garde of the avant-garde; the family magazines have bobbed their hair; politicians like to sound off on the cultural arts, and newspapers make literary history. So what has been lost?

And the Man With Time on His Hands: What is his opinion? Well, with a hint of pride and none of shame, family magazines now show teen-age boobs, nubby and bulging behind a scoopy blouse whose fabric is thin and blue as a gas flame. Loud colors coarsen every newsprint page. Entire bulletins are composed of headlines and illustrated with snapshots of Martian babies born to surprised Brazilian natives. Otherwise the world is restfully the same.

Ulrich goes on,

There is just something missing in everything, though you can’t put your finger on it, as if there had been a change in the blood or in the air; a mysterious disease has eaten away the previous period’s seeds of genius, but everything sparkles with novelty, and finally one has no way of knowing whether the world has really grown worse, or oneself merely older.

What has been lost is the magnetism which once discreetly ordered public affairs as though society were a pattern of metal shavings. Relationships have shifted a little and the orchestra is out of tune. Persons who would never have been taken seriously before have become famous.

I see that men have arrived with ladders and long-handled brooms to scrub the higher elevations of these whitish walls. A supervisor keeps tabs on their success at removing what I take to be construction smears, for this hostile passage has been recently remodeled. Texture-deprived, it is slick as a urinal. I am seventy, I grumble, feeling the seat of my pants in my lap. What am I doing in this tear in time?

2.

Robert Musil’s long, literally endless, novel, The Man Without Qualities, has finally been freshly and fully translated into a rich and resourceful English by Sophie Wilkins and Burton Pike. One feels obliged to be shocked that this uniquely great novel has been available before only in a truncated and uninspired British version; but surprise is hard to muster when neglect is one of our more practiced habits, and includes Hermann Broch and Karl Kraus, merely to mention a handy pair of Austrians. How often Musil must have despaired at the definition he was giving to his life, and the unpromising position he had put himself in; for if Sir Walter Scott (in Bertrand Russell’s famous example) was the author of Waverly so definitively that the phrase could have been conferred on him at birth like a prediction, Robert Musil, despite his earlier novel, Young Törless, and all of his weighty essays and significant stories, was fated to receive a definite description drenched in Musil’s own kind of irony, since he would be ultimately recognized as the author of a novel about a man who escapes every line destiny endeavors to draw around him, and whose lack of any limiting essence, one might wryly say, is his principal characterization.

In the United States, not noted for much acumen concerning matters of literary quality, the initial English translation was greeted with an animosity which cannot be ascribed to simple philistinism. As Christian Rogowski reports, Musil was described as an “almost intolerably bad writer,” “a sort of jet-powered literary no-good,” his style exhibited “a rather bumbling mass of Teutonic metaphysics.”1 The Times Literary Supplement’s favorable reception of the translation in London was judged to be part of a literary hoax.

Advertisement

What better place for a bit of bitter reflection and unhurried contemplation than this flotsam-littered sand bar in the middle of an airport night? With a book set in the shade of an oncoming war and written while in the shadow of the second. Seventeen hundred pages of the most intelligent and unflagging scrutiny modern life has ever had to bear—described with fondness by Françcois Peyret as a Foltermaschine—a torture machine. And what, in the garden of greatness (this novel presumes to wonder), has been crowding out genius if not common stupidity, so endearing and natural to man, so easily mistaken for talent and made to resemble progress and improvement?

The novel addresses this question in the essay-like meditations that Musil creates for Ulrich to stroll through while he is strolling Vienna’s streets. During the first of these, Ulrich concludes that there is “no great idea that stupidity could not put to its own uses; it can move in all directions, and put on all the guises of truth. The truth, by comparison, has only one appearance and only one path, and is always at a disadvantage.”

How appropriately in step with our own age; in which the stupids are the royal family, this suggestion is. Ulrich next imagines how Saint Thomas Aquinas (after staying up several centuries past his bedtime to conclude his researches, and therefore having put the reigning ideas both of his own time and future centuries in order) would step out of his medievally arched door into an Austrian street, only to have his nose surprised by the fierce passage of an electric trolley. Ulrich, chuckling, is himself confronted at that moment by a motorcyclist careening noisily past, its rider wearing a face with “the solemn self-importance of a howling child.” With characteristic rapidity he then remembers a magazine photo of a famous female tennis player in the strenuous posture of serving an ace, “on her face the expression of an English governess,” only to recollect immediately another image, this one of a swimming champion nakedly in the midst of her conditioning massage, a flexed knee held by a man in a doctor’s gown who gazes indifferently out of the picture, “as though this female flesh had been skinned and hung on a meat hook.”

Many of the themes which populate this novel—and “blockheadedness” is one of them—are also treated, more pointedly, in numerous essays which Musil labored over in his customary search for eloquence and precision. If we examine the lecture on stupidity which Musil gave in 1937,2 we discover how close, in these matters, the minds of Musil and Ulrich are, when, in that essay, he quotes, as if he were quoting from himself, Ulrich’s reflection in the novel that there is “no great idea that stupidity could not put to its own uses.” Musil’s view is wholly Platonic: when passion overcomes reason, stupidity results. And we allow our emotions to weaken our thought, to render it vague, ineffective, and mythical, because that is what we want. We prefer the evasions of superstition to the confrontational clarity of science and mathematics.

When one holds the two fat volumes of this handsome new edition, 1,774 pages, including drafts and notes (and unquestionably a major editing, translating, and publishing achievement), the first impression Musil’s novel gives one’s laden hands is of a stellar vastness, and, consequently, the maniacal scope of its author’s ambition; yet it is a vastness which the reader realized will be squeezed into roughly a twelve-month of time, that unluckily numbered year before the First World War arrives as the initial seizure in what will be the prolonged and repeatedly convulsive death of Western culture. Why should I, the Man With Time on His Hands wonders,…why should I undertake such a lengthy journey only to arrive at the unfinished station for an unbuilt town?

But this book was created to be incomplete, and if it had an end it would not be finished. As its writing went on, Musil kept delaying his journey with detours, and enlarging the novel’s scope and plan, a design which began by striking a Nietzschean and anti-Wagnerian note (genius is not an outpouring of Teutonic primitivism), while introducing Ulrich and establishing his positivist cast of mind within an Austrian Hungarian empire which Musil derisively calls “Kakanien”—a word formed from “Kaiser,” “King,” and “caca.”

The second section, “Pseudoreality Prevails,” which Musil thought of as the opening of the novel proper, is devoted to Ulrich’s “leave from life,” and his subsequent involvement in the Parallel Campaign. It is peopled by aristocrats, functionaries, bemedaled military men, and opportunists of every kind, but it is also marked by the appearance of the dim-witted Moosbrugger, who has brutally murdered a prostitute, and whose case fascinates Ulrich and the Romantic liberals, since he seems to symbolize the savage who has survived our oppressive civilizing to live on inside us like a strange fish in the deep sea. Ulrich’s childhood friend Clarisse, who tends to take up causes, becomes fascinated by Moosbrugger’s case and is determined to enlist Ulrich’s help in going to see him in prison; Ulrich is skeptical, yet finds himself preoccupied by the questions of will that arise from Moosbrugger’s helplessness in the face of his own destructive impulses.

The third part of the novel resuscitates a relationship between Ulrich and his twin sister, Agathe, which was one of the early seeds of The Man Without Qualities, but a seed so slow to germinate that it arrives as fallen fruit. The committee for the Parallel Campaign has by now broken into quarreling pieces. Much of this part remains unwritten. Philip Payne conjectures that Musil planned to balance the short introductory opening with a closing of similar length, called “A Kind of Ending,” to match “A Kind of Beginning,”3 but only the scantest of notes remain.

3.

For a time, in Musil’s youth, he had been a librarian, and soon he needed his knowledge of indexes and files in order to remember what he’d done, to find where he was, and keep track of all the creatures of his invention. The risk of conclusion increased in company with his desire to call it quits, since the novel was for Musil life itself by this time, and pulled on weary acceptance like a pair of familiar trousers and wore fastidious revulsion for its party shirt. According to Elias Canetti, Musil remembered every disagreement, and would worry an issue until he triumphed over it in his text, even if the quarrel took years to settle in his head. His novel could hardly keep up with every day’s debates, which became there little essays by Musil as the narrator who reflects on some of the questions Ulrich encounters from day to day, on the relation between logic and morality, for instance, the riddle of reality, various issues in mathematics, or the source of original sin.

Postponement was the plan; so, in addition to his additions, he revised, held portions back, wrote over proofs until every unprinted space was also dark, made alternative drafts of scenes and chapters, mourned whatever bit of text he had let escape from his fanatical concern for exact analysis to reach the embarrassment of print; because Musil polished not to achieve a finish or a shine, but (like every perfectionist) to accomplish the inconclusive—caught, as he was, in a race which only Zeno of Elea could have charted—edging closer and closer to assassination time, that other August, near enough perhaps to feel the first guns go off, but not close enough to hear in them the clap of doom.

You can’t claim disappointment if you haven’t first had hope; so, despite the fact that Musil was an ironist and analyst, and saw, to every issue, fifty sides, he was a dogged Utopian, too, a man who felt he could figure the human mess out, and that, eventually, the dark disturbing course of things would clear beneath his pen, as he purified his thought and sank fathoms through his feelings, the way, eventually, every muddy stream finds a pool in which to settle…yes, after he had pondered what he’d seen, and measured what he knew. Alas, however, solutions eluded him. Answers did not arrive. Ulrich suffers a nervous breakdown, a depression in which nothing seems to have any meaning. Perhaps mankind’s movements had no direction, offered no comfort, resisted reason, and perhaps its foolishness was so pandemic, it was pointless to find fault and fix blame. Musil could not honestly conclude his work with a claim to truth he had not found. But he could honestly go on. He could continue to try.

Yet if the novel remained penned within its period, its author did not. Decades of hindsight multiplied his hesitations, enriched his understanding, lent him outcomes he could not have initially foreseen, and so the book caught the spirit of the Twenties, endured the Thirties, suffered the inflation of every currency and observed the onset of the Third Reich, even as its narrative neared the very war Musil himself had fought in, not without relish either, for he was not a pacifist like Karl Kraus; there was a deep streak of belligerency in him; he kept his body healthy and his back stiff as a stereotype; he liked to box and wrestle; he believed that muscle gave the mind courage, and allowed it to be brutal….Ulrich himself could, undismayed, draw blood with his fists, as he does when set upon in the street by three mysteriously unmotivated men. Ulrich loses the fight only because “he apparently indulged in too much thinking.”

The male world of vigor and violence had a definite attraction for Musil, who was under the romantic and very German illusion that the body loved and fought, and no doubt hunted, while the mind removed itself to a calm peak where it could coldly overlook the catastrophe; that therefore the thoughtless life was Dionysian to a desirable degree; the animal closer to our real self; there was beauty in bashing and smashing; that for men to be men they had to act periodically like vicious little soccer thugs. “The fascination of such a fight,” Ulrich later explains to a young woman he is trying to seduce, lay in “the rare chance it offered in civilian life to perform so many varied, vigorous, yet precisely coordinated movements in response to barely perceptible signals at a speed that made conscious control quite impossible.”

The wound (a break between intellect and instinct, or idea and action, explanation and experience) which Musil would like to see healed appears in the novel’s opening paragraph, where, with pompous precision, a weather front is scientifically described. “A barometric low hung over the Atlantic….”

But this account contains an understanding of the weather, not the experience of it, so that Musil can caustically sum up its sentences more commonly as: “It was a fine day in August 1913.” For many decades, the mathematical sciences which Ulrich, Musil’s sometime spokesman, admires, had been interpreting Nature and Human Affairs in terms which were increasingly remote from common experience, and in a language which did not really appear appropriate to ordinary life. If heat has to do with the rapid movement of molecules, it nevertheless helps us very little with our enjoyment of “a fine day in August.”

The calendar, on the other hand, is an abstraction (though it does not appear in the weatherman’s spiel) which we have integrated into our lives so completely, we feel and smell “August”—its parched fields and blue skies—and the division of its days which the calendar contrives is as immediate in our minds as the feel of the sunshine on our bare arms or the wind-driven odor of distant wheat. Even the image of the month as a grid of numbered squares is not at all alienating. Here, the wound seems healed and measurement made reflective. Isotherms and isotheres, however, even if they are functioning as they should, are in no way as familiar to us as our cats asleep on the warm square tiles of the terrace. The words “August 1913” will warn us of the war in a way which will remain impossible for weather records.

The cleaners and sweepers, as well as the overseers of the cleaners and the sweepers, will take breaks in the bar, but even sitting down, nearly rubbing noses over the small tables, they will continue to shout, as though, really, they were all alone in this vast port, and wanted the walls to resound, to echo to keep them company; still, if Musil’s Ulrich were to observe this, in addition to noting the workers’ strange boisterousness, the pitch of their banter, the roars in their laughter, by degrees he would make social change of it, advancing his observations from each particular to its type, going from class to social circumstances, rising from there—and easily—to the cosmos. At the same time, Musil would be defining Ulrich’s mind, the mind of a man without qualities; that is, a man who refuses all definition, who remains plastic and possible.

It would be a mistake to confuse character with qualities, as Musil’s slight prose piece, translated by Peter Wortsman as “A Man without Character,” confirms.4 A man without character is like an actor who prefers to be a cipher in order to accept other people’s sums. Ulrich has a manner; he has dispositions, preferences, habits, quirks. None of these things, however, will serve to define him. He is not one of the humors. Furthermore, in any habit he can see the doorway which will release him from it; in any disposition, its opposite; in any preference, reasons for rejection; for any Jesus, the value of Judas.

Unlike the existentialist hero, whose existence preceded essence, Ulrich refuses to make the commitment which might give a “purpose” to his life. Though he has friends and mistresses, he is not “the lover of,” and although he has opinions, he belongs to no party, is defined by no principle, has no loyalties (to local mores, State, or status). Even Ulrich’s physical traits alter as his opinions of himself, as well as his circumstances, shift: when angry or sexually in command, he is tall, broad, and muscular; while, when tenderly moved by books or music or the mysteries of Being, he is as delicate, dark, and soft, he believes, as a jellyfish afloat.

Schoolboy friendships are formed too early to express more than the accident of proximity, though they fade the way one lets go of a customary childhood, with guilt and reluctance. Ulrich’s boyhood friend Walter, Wagnerian, pianist of passion, unhappy chum, learns to loathe him as only a former friend can, since Ulrich has nothing but contempt for music and its emotionalism, and for Walter’s fancied ability to appreciate the rich fullness of life, “this capacity to experience more is one of the earliest and subtlest signs by which mediocrity can be recognized,” Ulrich says. It is Walter, the failed genius, who first describes Ulrich as a man without qualities.

“His appearance gives no clue to what his profession might be, and yet he doesn’t look like a man without a profession either. Consider what he’s like: He always knows what to do. He knows how to gaze into a woman’s eyes. He can put his mind to any question at any time. He can box. He is gifted, strong-willed, open-minded, fearless, tenacious, dashing, circumspect—why quibble, suppose we grant him all those qualities—yet he has none of them! They’ve made him what he is, they’ve set his course for him, and yet they don’t belong to him. When he is angry, something in him laughs. When he is sad, he is up to something. When something moves him, he turns against it. He’ll always see a good side to every bad action. What he thinks of anything will always depend on some possible context—nothing is, to him, what it is; everything is subject to change, in flux, part of a whole, of an infinite number of wholes presumably adding up to a superwhole that, however, he knows nothing about. So every answer he gives is only a partial answer, every feeling only an opinion, and he never cares what something is, only ‘how’ it is—some extraneous seasoning that somehow goes along with it, that’s what interests him.”

Against our popular pastime—the search for an identity, and the consequential renunciation of individuality—Ulrich’s evasiveness is more than a refusal to play, it is a moral challenge. In his terms, it makes sense to admit, for instance, that your parents came from Poland, but no sense to boast that they are Polish. When people who write novels begin to consider themselves novelists, they also begin to write their fictions for that reason. Before they know it they are Afro-American, gay, and post-mod. Now they have a role to roll around in. Ulrich will admit to living in Austria, to having affairs, to participating in this or that plan or program, but not to being Austrian, a philanderer, or a volunteer.

It is the coolly scientific and reductive, as well as the disturbingly relative, that seem to characterize most accurately Ulrich’s mind. In many ways like Musil’s own, it is both romantic and hard-boiled. Musil, whose father was an engineer, was always adept with numbers, and inclined to favor whatever was precise and orderly, comprehensible and connected; but he was overwhelmed by Nietzsche and Emerson in his youth; the result was a romantically rebellious union of yeaand-nay, skepticism and idealism, which was irresistible. As Musil developed, he put Nietzsche’s revolutionary notions to use in demolishing sham, convention, and shallow, socially acceptable thinking; but he did this in support of an analytic, material-minded positivism, which was practiced by the Vienna Circle, and by his teacher, Carl Stumpf, and by the subject of his dissertation, Ernst Mach.

Ulrich is far more likely to replace passion with statistics than Musil was. In my bar, Ulrich would note the number of stranded passengers, take account of their class and business, and wonder whether tonight’s casualties were average for such cancellations, and whether more or less coffee was drunk when the students were German rather than, say, French. Ulrich’s creator, however, was very aware of the protective and sterile character of such statistics.

4.

A tall, thin, bearded black man has slipped in and found a stool from which to watch the TV screen. Soon he smiles at something he has seen. And there is, among a group of casual youngish Texas business types, an Oriental I had not noticed before, boasting in loud, drunken, heavily accented English about his religion. He is being humored, genially laughed at, and answered in soft south Texas tones. One of the group is a young woman I had already observed being treated with the cordial indifference customarily accorded low-salaried secretaries. She has a light subservient titter. And now I am able to decipher a bit of what the Oriental is saying, enough to figure out he is extolling a kind of odd-God Christianity. Musil would have been amused.

Amused … His great book is written in ink and sadness, with a wit that only salts its tears. The atmosphere of the bar, the growing lateness of the night, the mutter of the television, the sudden bursts of noise which break in upon our little group’s slippered life: they belong in his world too, for his world and ours are indistinguishable. I read my circumstances, I see his creatures and their contradictions as if they were trying to find some sleep beside me. Should I take a pointless nervous turn about, or go on to section 78, “Diotima’s metamorphoses”?

If Ulrich is tough and derisive, Diotima, whose salon becomes a center for the Campaign, is confused and emotional. She has ideals so high she cannot see how hollow they are. What else but the air of their emptiness keeps them up? Well, the chitchat of her Vienna salon for one, a place where refinement is practiced as diligently as scales on the piano. Before she married Vice-Consul Tuzzi, who leads an ant’s busy straight-line life (a man described by Musil as looking “like a leather steamer trunk with two dark eyes”), Diotima may have had “something fresh and natural” in her, “an intuitive sensibility wrapped in the propriety she wore like a cloak threadbare from too much brushing, something she now called her soul and rediscovered in Maeterlinck’s batik-wrapped metaphysics.” Her husband has ignited a sexual fire in his wife, but he has failed to keep it safely in its place behind the hearth. It is a fire which has become wild, consuming only bric-a-brac right now, but burning more brightly with every evening of his neglect—a neglect not of intercourse alone, but of discourse and dalliance—which leads her to flirt with Ulrich and others involved in the Campaign.

Diotima is naive enough to invite a Prussian industrialist (played here by Paul Arnheim, but in real life Walther Rathenau, the German politician) to participate in putting on the celebration. Arnheim is a perfect foil for Ulrich because he is a man of many qualities: a rich, successful Jew, an author of books on many cultural subjects, socially adept, politically concerned—someone who believes he has brought into harmony, within himself, power and benevolence, money and refinement. And he is happy to help Austria out in any case he can because he is really after the nation’s Galician oil.

Diotima (was she named for the Mantuan seer in Plato’s Symposium or for Hyperion’s lady-love in Hölderlin’s epistolary novel, Hyperion? few were called by this name even in Plato’s day)… Diotima’s naiveté has a less innocent ground, an unfocused lust which expresses itself in misty rainbow-hued idealism. To satisfy the one, she tries to appoint herself Paul Arnheim’s mistress, and slyly buys a lot of underduds; to satisfy the other, she asks Paul Arnheim to direct her “celebration.” However, Arnheim is ruled by profit not by passion, and therefore he is governed by conventionality as well; whereas Diotima is willing to risk status to satisfy her “soul.” Both embrace the appearances which their definitions solicit. “To appear,” after all, is better than “to be,” for one may unfortunately “be” without the guarantees of “seeming,” and seeming is where all benefit is, as Thrasymachus had argued in the first book of the Republic. Since Diotima’s and Arnheim’s “appearances” are so contrary in character, the pair fall apart like hinges.

Rising from the vertical creases of his trousers, Arnheim’s body seemed to stand there in the godlike solitude of a towering mountain. United with him through the valley between them, Diotima rose on the other side, luminous with solitude, in her fashionable dress of the period with its puffed sleeves on the upper arms, the artful pleats over the bosom widening above the stomach, the skirt narrowing again below the knees to cling to her calves.

The German students appear to be losing their shared nature in their common condition. Sleepiness is pulling them apart, drowsiness is making them assume postures of particularity: one young woman has part of a fist in her mouth. The TV has just concluded a scrap of Die Walküre. Part of an ad? But people snickered. Part of a joke? Highyaho, or something? Wagner torn apart by the advertising furies: that would please Ulrich, who condemns everything Wagnerian with an ungenerous ferocity. His positivist point of view has little patience with theories of inspiration and the emotional states which masterpieces are, in turn, supposed to create. Ulrich’s married friends, Walter and Clarisse (in this book, last names are in short supply), are characters around whom the initial notions for the novel circled, rather ineffectually, for years. They represent the domestication of Nietzsche’s superman. Walter is a musician, under Wagner’s spell, and everywhere advertised, especially by his wife, Clarisse, as a genius. If Paul Arnheim is a man of many definitions, Walter is only possessed by one.

When Walter and Clarisse play duets, as though mutually making solitary love, they reach their sensual transports in different ways. Her playing is hard and colorless, yet something will finally tear itself loose inside her and threaten to fly away with her spirit. It is, I suspect, the madness which will overtake her later in the book. Clarisse wants to mate in order to make geniuses the way Isadora Duncan did. She pushes her husband toward such heights of achievement, and she will proposition Ulrich with this result in mind, an especially important one since it invokes the “genius as savior” theme with which the book begins, and which seems to have generated it. Ulrich’s disciplined and unsentimental idea of genius has nothing in common with Clarisse’s, however, or her ambitions for Walter. If Ulrich is free when inside himself, Walter is bound by the absurd idea that he must first establish himself as a genius before he can achieve anything of worth.

Two members of the airport police are escorting the tall, bearded black man from the bar. They let him walk away out of sight down the corridor, his blue shirttail showing beneath his worn black jacket. One cop shakes his head, the other snorts. Together they stroll in the opposite direction. Is the man they have expelled from this dismal paradise one of the LaGuardia homeless I have read about? Must he keep moving to stay out of jail like the fly that’s safe if it never lights? Has Moosbrugger joined my cast of characters here, the sinister outsider—a rapist and murderer—who fascinates both Ulrich and Clarisse? Moosbrugger is one of this fiction’s great creations, based on an actual case so that Musil might feel he was analyzing reality rather than merely projecting a dark part of his mind, the shadow of his hateful thought, like soil tracked on a rug.

Musil saw in the case which was reported in the press, and then in his fictional surrogate, an instance of a mind without a mind, a man whose madness might free him of moral responsibility, but, in so doing, might free him of hypocrisy and social conformity as well. Moosbrugger, the murderer of a prostitute, whose consciousness could only be inferred, Moosbrugger, the man the police questioned to discover his guilt, Moosbrugger, the man in the dock, badgered by lawyers intent on his competence, was he—haunted by hallucinations, his savage rage set off by a single gesture—Europe itself, ready to go to war, or were wars so organized and disciplined they had to be the reason inside what was called insanity, rather than the insanity inside what passed as reason?

The homeless man—might we imagine?—represents one of the great failures of our consumer society, since he has declined to have any commercial purpose; he cannot even receive junk mail. Madness has similarly stripped Moosbrugger of the sly cruelties of convention and the shams of manners, so that now he, too, has no definition. Would a man without qualities remain a man? The thin, bearded fellow offered the policemen only a faint smile when he saw them. He left his stool as he knew he must because it is important for them that he not appear homeless. Had he a briefcase or a drink, perhaps the cops would have left him alone. Moosbrugger, too, smiles in his cell; he smiles because he is bored; he smiles at the walls; when he is aware he is being watched, he smiles once more. He is no easier for the authorities to define than Ulrich is to figure out for his friends.

What has made Moosbrugger the center of such scrutiny? It is not merely that he is none too bright and has a weak hold on conventional reality. He is minding his own business when a prostitute persistently solicits him. He tries to ignore her, evade her, the way we do beggars. He hurries his step; he lengthens his stride. But she continues to be there like a length of sleeve, something ugly like snot on a finger which can’t be flicked off, a splinter (which is what Musil writes) embedded in the skin. He tries to hide; he lies down in a patch of darkness behind a fence; he pretends to fall asleep, and plans to sneak away later when she’s asleep too. Yet there she is once more like a creak in a door. She twines her arms about his neck when he tries to leave. It is then that Moosbrugger removes the girl as you would a sliver, an evil growth, a bad dream.

For the authorities who arrest him, Moosbrugger has clearly lured the girl from busy paths into a concealing darkness, there to stab her repeatedly, as though he had paid for his pleasure, and was getting off.

A newspaper report of the bloody crime brings Moosbrugger to Ulrich’s notice, but it is not the crime which interests him, nor is Moosbrugger’s guilt in question, although he is so fascinated by the case that he attends some of the trial. It is a matter of Moosbrugger’s responsibility, responsibility which creates the whodunit. If the life Moosbrugger had been leading before the murder had been as inauthentic as that of most men; and the whore’s unwanted solicitations, the fears she aroused, had momentarily removed the mask (since he had begun by shrugging her away); then would Moosbrugger’s action be that of the real, the inner ogre with all his sham manners dropped, his roles abandoned like a hated house? Does the structure of society—its classes, fashions, mores, patterns of behavior—merely serve to bandage and to hide pathology? Were we suddenly able to become invisible (Plato conjectures in his fable of Gyges and the ring), would we cheat, steal, and seduce, as fearlessly as in fantasy?

Furthermore, when we say we know something of ourselves, is not the self we know and acknowledge only an actor, a fabrication, a dime-store definition? So Moosbrugger without his ordinary habits and pattern of life would be unrecognizable even to himself. Who am I at play’s end, if I am Hamlet to myself? An actor no longer alive. On the other hand, if an inner demon did it (whatever the deed is), hang him; don’t hang Moosbrugger, who, if he’d been his shakily assumed social self, would have calmly taken the splinter out and sucked solicitously on the little wound. Even Moosbrugger is not so huge a fool as to mistake an annoying woman for an unpleasant sliver of wood.

Ulrich (if the Man With Time on his Hands comprehends the idea of a Man without Qualities with any correctness) stands between the theatrical social role-player (whose real self doesn’t do what the actor does, except insofar as his real self accepts the part) and any bestial human core, for he is neither in the grasp of convention nor in the grip of the Id. The difference in Ulrich’s case lies in the presence of reason which sees through the first and shields him from the second. Most actual action is a messy mix of the permitted, the possible, and the desired.

Suddenly Ulrich saw the whole thing in the comical light of the question whether, given that there was certainly an abundance of mind around, the only thing wrong was that mind itself was devoid of mind… At this moment, there were two Ulrichs, walking side by side. One took in the scene with a smile and thought: So this is the stage on which I once hoped to play a part…. The other had his fists clenched in pain and rage. He was the less visible of the two and was searching for a magic formula, a possible handle to grasp, the real mind of the mind, the missing piece, perhaps only a small one, that would close the broken circle. This second Ulrich had no words at his disposal. Words leap like monkeys from tree to tree, but in that dark place where a man has his roots he is deprived of their kind mediation.

My tall, thin, briefly bearded man is back, lurking in the passage … well, not exactly lurking, bobbing rather, as if in an eddy, and now he drifts in and settles in a discreet corner where the TV can be viewed. “Anyone can conceive of a man’s life flowing along like a brook, but what Moosbugger felt was his life flowing like a brook through a vast, still lake.”

I, on the other hand, have outfitted my small spot: pen and papers, briefcase, book, cup of coffee, pool of light—uncomfy cozy as can be. Plop in the part of the book that Ulrich calls “the Utopia of Essayism,” but what feels to me more like the middle of the night. The essay is to other forms of writing as the Man Without Qualities is to other forms of men. “… An essay is…the unique and unalterable form assumed by a man’s inner life in a decisive thought.” The essayist occupies that middle ground between the scholar who says he seeks the truth, and the novelist, for instance, whose aim is to freely exercise his subjectivity. Musil’s odd novel, and Ulrich’s odd mind, reject both certainty and subjectivity, as each believes the essay does. “Nothing is more foreign” to the essay

than the irresponsible and half-baked quality of thought known as subjectivism. Terms like true and false, wise and unwise, are equally inapplicable, and yet the essay is subject to laws that are no less strict for appearing to be delicate and ineffable.

The essayist is “a master of the inner hovering life.”

5.

I was beginning to fear this night would never end. I consulted my watch again and again. Every second stood for that arrow’s flight which was made, not of motion, but of a series of stills; yet I was equally afraid it would lapse like a love affair, and I’d lose Musil’s mood and mind; because in the morning more flights would be canceled; I would stand in still more snail-like queues, suffering an airline which could not find sufficient incompetents to staff its desks. Hectored now by the hallway’s matron, the homeless man, his hands in the side pockets of his windbreaker, rises without sound or expression and sidles out between sleeping forms. Behind that calm and even face, what sort of storm is brewing? How long may such humiliations be endured, night after day and day after night? He will merry-go-round it and reappear here, only to be scolded once again, and impassively to fall and rise on his rod like a plaster steed.

What can we say that will be adequate to Musil’s slow, meditative style, writing which is both analytic and lyrical, witty and sensuous? For it is not the novel’s situation; it is not the richly realized characters; it is not even its observations and ideas that makes The Man Without Qualities a masterpiece. In it Musil’s mind meditates on Ulrich’s mind while Ulrich’s mind is meditating on that, say, of his mistress or Paul Arnheim or Diotima. Musil thinks through, weighs and evaluates, Clarisse’s ardent consciousness while accurately rendering her more limited awareness of herself and the world. Ulrich explains Clarisse to himself while Musil explains both of them by means of Ulrich’s explanation.

In many ways, in taste, temperament, and ambition, Musil is a nineteenth-century novelist, viewing Joyce with the same distaste as Virginia Woolf did. He is vain and competitive, too, especially regarding his rival, Hermann Broch, whose generosity of character he could not match. When Franz Blei wrote a brief review called “A Guide to Five Books” for the Prager Presse, as Paul Michael Lützeler reports in his fine biography of Broch, Musil complained to him bitterly that Blei had devoted three more lines to Broch (all of thirteen) than to him (only ten). Nor can we find anything to admire in his belief that Broch was borrowing his ideas, writing in his diary, “Broch—leaning on me—if you lean against a wall your whole suit becomes covered with white marks—without its being plagiarism.” Worse, Musil writes Broch in this vein, injuring a man who had supported him and would continue to support him, even monetarily.

Yet Musil’s style is as antagonistic to narration, plot, and action as any modernist’s, and only Proust can give us an equally mentalized slow-motion world. Even if Ulrich repeatedly complains (in the manner of Hamlet) that thought inhibits action, such concern is not permitted to inhibit the slow honeyed spread of Musil’s prose.

Later, in Part III of the book—and much too late, in my opinion—Agathe, Ulrich’s twin sister, appears like an afterthought larger than its predecessor. Together in a provincial town, far from the madding social life of Vienna, they walk and talk and meditate. She is recovered and loved as Ulrich’s other, sought-after half, and represents the possible resolution of the conflict between “head and heart” (to put it crudely) which has been tormenting him. Since they become as inseparable as Siamese twins, gossip follows their dog. This wholly forbidden love, for that is clearly what they share, so long as it is simply felt and not so simply consummated, allows them to seem scandalous (thus achieving the necessary affront to bourgeois morals), while feeling about one another only what brother and sister “should.” We are now in the realm of unfinished versions, however, and critical opinion is sharply divided about what Musil intended or would have ultimately done. For what it’s worth, I favor the view that Ulrich and Agatha remain forever on the verge. Ulrich is finally able to live the intuitive, emotional, and “feminine” in himself because his “femininity” now loves him.

My own attention has been divided between LaGuardia and Austria, and very much of the time Musil’s world has overcome my own. Critics have suggested that this novel is best read in bits and pieces, like the Bible, a verse or two at a time, and there is a good deal of wisdom in such advice; however, I believe one must at least begin with a long run into it, so that the reader begins to feel wholly immersed in Musilage. His unhurried pace insists on baptismal immersion, not omitting the heel; the unusual multiply-reflected consciousness he constructs requires a prolonged attention; and the force of local metaphors, of wit and perspicacious description, will otherwise be lost.

Oddly enough, it seems to me that the possibility of acting as a real and free self in society, of remaining whole while joining the whole, a unity which Ulrich seeks, has been present all along, because even in a narrative which is picturing the problem, there is the presence, in the prose itself, of the solution: the formal and the sensuous, the abstract and the factual, the mental and the emotional, the analytic and the mystical, brought together in lines which resolutely avoid the conventional and continually discover the strange ambiguous indefinability of things.

I am taking a little walk around, myself, to stretch the limbs and shift my eyes from pages to people. Folks are appearing. Facilities are slowly being staffed. In another chamber, a homeless man is leaning against a pillar as polished as plastic. I think he is watching the people passing. He is watching me. When the fog lifts in St. Louis, when I return home, I mean to look up Hölderlin’s epigraph to Hyperion—the Hermit in Greece because I think it may suit this matchless novel.

And I do. It does.

Non coerceri maximo, contineri minimo, divinum est.

Not to be confined by the greatest, yet to be contained within the smallest, is divine.

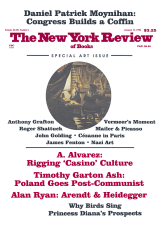

This Issue

January 11, 1996

-

1

In Distinguished Outsider: Robert Musil and His Critics (Columbia, South Carolina, 1994), p. 23.

↩ -

2

Edited and translated by Burton Pike and David S. Luft in Precision and Soul: Essays and Addresses (University of Chicago Press, 1990).

↩ -

3

In the collection, Posthumous Papers of a Living Author (Marsilio, 1987).

↩ -

4

In Robert Musil’s ‘The Man Without Qualities’ (Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 58.

↩