1.

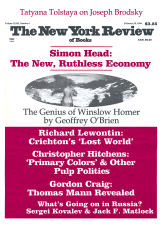

The Winslow Homer show recently on view at the National Gallery, and soon to open in Boston and New York, consists of more than 240 objects: oil paintings, watercolors, drawings, and engravings, all the way down to paintboxes and brushes and well-thumbed manuals of color theory. To look at the whole of it is a distinctly nineteenth-century kind of experience, analogous to reading in consecutive order the complete works of Thomas Hardy, or surveying on foot the headwaters of the Missouri, or taking inventory of Theodore Roosevelt’s house at Sagamore Hill. There is little in the way of sudden leaps or eccentric digressions: no fever dreams or mad gambles. Progress is made in steady increments, and one must pay attention at each slight bend in the road.

This may not be the ideal way to look at Winslow Homer’s, or anyone’s, art—scores of paintings are inevitably crowded into invisibility by their neighbors—but it does instill a healthy respect for the sheer stamina of the artist. The impression is of a gathering precision and force attained through methodical experiment and stubborn persistence. Winslow Homer, our invisible host or (more appropriately) trail guide, begins to figure in imagination as a particular prototype of nineteenth-century man: reserved to the point of taciturnity, ruggedly self-sufficient, an artist with a good commercial head and a sportsman’s feeling for the outdoors, outwardly untainted by scandal or controversy, inwardly unknowable and not wishing to be known.

That wish not to be known has bothered art historians inordinately. It’s as if Homer had reneged on an implicit contract to articulate his inner motives for the benefit of future chroniclers. He certainly didn’t make their work easier for them; as the curators of the exhibit, Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr., and Franklin Kelly, put it in their admirably thorough catalog, he was “reticent almost to the point of secretiveness about the meanings of his creations, and protective of his privacy almost to the point of reclusiveness.”

The man who said that “the most interesting part of my life is of no concern to the public” left little in the way of personal details for biographers to go to work on, no marriage or known love affairs, no record of intimate friendships, nothing even resembling a strong emotional episode. Not so much, in fact, as a spate of purple prose. Homer went about his work in plain view but in silence, consistently refusing to make statements of general intention or ultimate significance. His letters reveal chiefly that he thought his work was very good and sometimes outstanding, and that it was intended to speak for itself. An attempt to elicit further information about the narrative implications of The Gulf Stream provoked a characteristic burst of sarcasm: “I regret very much that I have painted a picture that requires any description…. You can tell these ladies that the unfortunate negro who now is so dazed and parboiled—will be rescued & returned to his friends and home & ever after live happily.”

One senses more than a little of the control freak about Homer, a control freak now to some extent outfoxed by a posterity determined to have its way with him. He exercised many forms of control: over his medium (attained, despite scanty training, through rigorous self-discipline), over his social contacts (he cut them back drastically), over the sale and exhibition of his works (he took pains to limit the number of items on the market, and on occasion insisted that viewers stand at a prescribed distance from certain of his paintings).

Homer could hardly have anticipated the mania of twentieth-century scholars for aesthetic accountability, for nailing down every stray detail and motive, and their tendency to mutter balefully about repression and sublimation when they find that data has been deliberately withheld by the subject. Yet his probable reaction to such scrutiny is clear from his irascible responses to every attempt to pin him down or draw him out. Asked to provide material for a biography, he replies: “It may seem ungrateful to you…that I should not agree with you in regard to that proposed sketch of my life—But I think it would probably kill me.” Pressed to provide titles for some of his Adirondack watercolors, he writes to his dealer: “The two fishermen are fishing for trout—call them Thom—Dick—or Harry—The two log pictures are on the Hudson river anywhere you choose to place them—The trout is a trout—.”

It is not reticence or evasion that comes to mind, however, while we hike among the marks left by this life. The world is very much with us here, from the trees thick with sharpshooters to the beaches and mountains dotted with post-bellum picnickers, from the sheepfolds of Houghton Farm to the trout streams, tropical harbors, and wave-dashed cliffs of the later work. Seen in this comprehensive fashion the work begins to resemble a pictorial tour—the coast of Maine, the North Sea, the woods of Virginia, the lakes of the Adirondacks—each locale to be studied for its particularities of coloring and vegetation, and for the characteristic occupations of its inhabitants. Homer’s work will not suffer itself to be looked at entirely in abstract terms of color and mass and pattern. To think about it at all is to think about temperature and wind velocity and shifts of light, and about the practical adjustments that humans make to unavoidable conditions.

Advertisement

He paints, so to speak, in prose, by which I don’t mean to suggest anything cluttered or plodding. It isn’t the ancestral prose of Washington Irving or James Fenimore Cooper that comes to mind, but the modern idiom of Homer’s contemporaries, William Dean Howells or the young Henry James, the literary cosmopolites who learned to leave out superfluous details and rhetorical persiflage in favor of exact observation, an unwillingness to force the issue, an appreciation of details for their own sake. Homer appears to hew without exaggeration to the contours of what is observable.

This is of course an illusion; Homer’s effect of impromptu reportage owes much to sleight of hand. Most of the time he is not showing what happens to be there but rather what he has placed there. Nothing could be more calculated than the way figures and props are dropped into (or removed from) their surroundings. The catalog emphasizes Homer’s collage-like approach to picture-making, particularly during his years as a professional illustrator, an approach comparable to industrial methods relying on interchangeable parts. He often re-used the same figures in different contexts; the same milkmaid with the same bucket and milking stool shows up in at least four different works. He would cut up drawings and paintings in order to generate different compositions, or adapt works from one medium to another and in the process add or subtract crucial pictorial and narrative elements.

In his later years a similar approach sometimes led him to paint over portions of earlier paintings so as to drastically change their meaning. The woman with child walking along a stretch of sea-swept Maine coast in The Gale of 1893 began life ten years earlier (The Coming Away of the Gale) on a waterfront path in the English village of Cullercoats, passing in front of a group of men geared to embark on a sea rescue. The distressed ship under full sail which a lifeboat crew prepared to assist in The Signal of Distress of 1890 had become, two years after the painting’s first exhibition, a mastless wreck with no sign of life.

Homer’s flair for recycling and repositioning has everything to do with techniques developed over a lengthy and successful career as a commercial illustrator adept at picturing whatever Harper’s Weekly or Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper might require of him, from society balls and skating parties to the interiors of flophouses and opium dens. For nearly twenty years his sketches and paintings were reproduced as engravings illustrating everything from sheet music to popular novels, and filling the pages of popular magazines with requisite scenes of dancing, bathing, hiking, and other forms of contemporary leisure.

His illustrations exhibit little of the melodramatic facility typical of the day; the most gaudily picturesque subjects become strangely dour in his hands. Even in his commercial work there is a gravity which resists easy reading, easy tears or laughter. Yet the painter whom Henry James perceived (in an 1875 review) as upholding “purely pictorial values” (“the artist turns his back squarely and frankly upon literature”) was also, in his earliest training and experience, very much a journalist. It was as a war reporter of sorts, in his sketches and paintings of Civil War camp life, that he first made a major public impression (so much so that it was decades before he could surpass the impact of his first great success, Prisoners from the Front of 1866). He remained enough of a journalist to take as the subject of one of his last and greatest paintings—Searchlight on Harbor Entrance, Santiago de Cuba (1901)—the newly revealed properties of electric light.

His strength as a reporter is the detachment already evident in his earliest known painting, The Sharpshooter on Picket Duty (1863). Here, as so often afterward, he delineates an action with clarity but in something of a void, the void of a snapshot cut off from any wider context. The sharpshooter is perched in a tree, peering through the telescopic sights of his rifle and poised to shoot, but we cannot see his face or altogether grasp the situation in which he is caught up. The crucial action, the death of which he may be the cause, occurs off-screen, as it were, in the line connecting his averted gaze and the invisible target toward which his face is turned. At the same time, the viewer’s vantage point suggests that the sharpshooter might just as easily figure as a target in someone else’s sights.

Advertisement

Homer depicts a portion of a trajectory, and the result would be intolerably could if it were not for the warmth of curiosity with which every detail is presented. The painting’s unheroic mood is confirmed by a letter in which Homer noted that the long-distance killing practiced by sharpshooters “struck me as being as near murder as anything I could think of in connection with the army & I always had a horror of that branch of the service.”

When Homer sets up an apparently conventional scene he manages to curtail the anticipated emotional reading. He is the great American painter of ambiguous situations for the nineteenth century as Hopper will be for the twentieth. In the period from the end of the Civil War to the late 1870s, he explored a varied range of American subjects in a way that repeatedly evokes (whether intentionally or not) the writers of the period: Mark Twain’s boys at play, William Dean Howells’s modern young women, George Washington Cable’s scenes of life among Southern blacks, Sarah Orne Jewett’s fishing villages of the Maine coast.

His advantage over the novelists is freedom from the complications of plot and the inherited burdens of moral interpretation. Since he is not obliged to look for motives or resolutions, he can thrive on a persistent sense of incompletion. “About that which one cannot speak one must be silent”; Homer is completely at home in the silence where painting concedes the limits of its power to explicate or elaborate.

In his paintings of the 1870s, Homer covers a world he will eventually abandon, an outwardly benign world of children’s games and seaside pleasure parties, croquet and carnivals, rural schoolhouses and sheepfolds. Often he depicts scenes of leisure, but he takes a distanced view of those at play, whether it’s the boys outside the country schoolhouse in Snap the Whip or the fashionable day-trippers of Long Branch; he presents the reckless energy of the first scene and the erotic elegance of the second without participating in either. The wonderful and rather bizarre paintings of female croquet players in their hoop skirts—figures as immobile and abstract as the hayricks in Martin Johnson Heade’s salt-marsh paintings—turn play into hieratic geometry.

Homer’s renowned paintings of children have a down-to-earth glumness which exempts them from sentimentality. His boys, bland little Buddhas with their pudding-bowl hats and expressionless faces, enjoy a youthful pleasure outwardly indistinguishable from wary indolence. Their play, in Snap the Whip, is so carefully composed that it begins to look more like choreographed work; the Boys in a Pasture (1874), if they are not lost in innocent communion with their surroundings, could as easily be sunk in boredom or even entertaining malevolent projects.

So often Homer’s strength is a matter of reserve, of refraining from being too specific or explicit. The extra touch that would make a scene heartrending or satirical is precisely the one he leaves out. Instead he cultivates an air of suspended judgment. His paintings lend themselves to multiple readings because he has not cluttered them up with his own interpretations. The Carnival (1877) is a genre scene described by Homer as “giving a chance for the employment of primary colors and lively effects,” yet (like his other remarkable scenes of black life in the post-bellum South) it avoids the effect of easy exoticism or coy humor. He creates an uncanny impression of stepping out of the way so as to permit a glimpse of the subject without interference from the artist.

2.

The exhibition can be read as a history of what he chose to look at. From his origins as an illustrator for hire, Homer becomes more and more selective about what he will undertake to paint. Children and women, who proliferate in the first half of his career, become increasingly scarce and then disappear altogether; the men who remain on view are after a while those of the mountains and backwoods only; finally there is little left but rocks and waves.

It is almost too tempting to decipher these scenes as a hidden drama about the disappearance of the feminine. The motives for such a drama are, of course, lost in that carefully concealed private life, in that unwritten biography which Homer thought would probably kill him. It would be possible, however, to look at the paintings exclusively for their division of parts, to sort them by scenes of men alone, of women alone, of women and men coexisting in the same space while remaining clearly and insuperably separated. That separateness—evident even in the occasional scenes of chaste and bashful pastoral courtship—is the premise of every social occasion. Homer paints the spaces between people with rare exactitude. Crowds for Homer are collections of isolated individuals; he must be the least festive painter of festivities.

The women Homer paints in the Seventies are very much American heroines; they could be the protagonists—determined and unafraid and effortlessly compassionate—of books by Helen Hunt Jackson, or, for that matter, Zane Grey. They are young, enjoy vigorous health, and are either fashionable or (in a bucolic way) fashionably unfashionable. They play croquet; they bathe in the sea; they teach school or work in mills; they tend sheep and milk cows; they sound the dinner horn with what looks to be a formidable blast.

There are other, more languorous women whose portraits provide Homer an opportunity to try out the latest fashions in aesthetic effects. The decorative flattening out of space in Morning Glories (1873), with the flowers laid out in the foreground as on a tile or panel for the home of a woman much like the one depicted in the painting, and the refined prettiness of The New Novel (1877), with its voluptuously horizontal format and stylized bands of color, have almost the air of demonstrations. Homer shows that he is capable of these feats of exquisiteness, but not that he is compelled to them. They seem tryouts for a play in which he finally decides he has no real desire to participate.

Somewhat apart from these paintings of unidentified women is the Portrait of Helena De Kay (1871–1872), a woman central to what then constituted the American literary and artistic world: granddaughter of Joseph Rodman Drake (a poet still much admired in Homer’s day), sister of the art critic Charles De Kay, wife of the influential editor and poet Richard Watson Gilder, and herself a painter, she presided over perhaps the most sophisticated salon in Manhattan. The catalog teases with hints of a crucial emotional event in. Homer’s secret life, describing his friendship with Helena De Kay as “a relationship that seems to have been, at least on Homer’s part, more intense than casual,” “what can only have been a close and perhaps intimate relationship,” “[Gilder’s] wife’s not entirely unrequited earlier love.” This may be little more than conjecture intended to fill in a much-needed background story. Whatever the nature of De Kay’s relationship with Homer, she clearly is not only the subject of the portrait, but the type of person most likely to be able to look at it with understanding, an educated connoisseur of the fine arts: his real audience, in fact. It is one of the rare occasions when he depicts the world for which his canvases were actually destined.

In the painting De Kay sits on a divan in an otherwise bare room, dressed in black and with a book clutched in her hands, her head bowed forward, her gaze directed downward as if in distraction: “all alone / She sitteth in thought-trouble, maidenwise,” as her husband wrote in a sonnet inspired by the painting. This turning of the eyes downward, to the side, or altogether away occurs so frequently in Homer’s paintings as to seem almost a tic. The difficulty one feels in knowing his people—most especially his women—has much to do with one’s being unable to look them in the eye.

Like the sharpshooter they are looking elsewhere, whether beyond the frame or inward, in any event into a space that the painting cannot visibly encompass but that it manages somehow to fold into itself precisely through that movement of aversion or evasion. It is the woman’s action (if it can be called such) and its relation to her surroundings, rather than the woman herself, that attracts his interest. In these works he is not so much a painter of women as a painter within whose field of vision women are often found. Of Woman, the grand eroticized object of so much overheated nineteenth-century painting, there is barely a trace.

In two paintings—among his least typical and most haunting—the presence of a pair of women creates mysterious possibilities that are elsewhere inaccessible. Promenade on the Beach (1880), in which two fancifully dressed young women walking arm in arm glance with a mixture of anxiety and curiosity at something at sea, something once again just beyond the edge of the frame, might be a novelistic episode from Wilkie Collins or Mrs. Henry Wood. The painting has a gothic strangeness otherwise rare in Homer’s work, as if between them the fluttering of a Japanese fan in one woman’s hand and the portentous darkening of the blue and purple sky created a zone in which genuinely unanticipated events might occur.

Even more remarkable is A Summer Night (1890, lent by the Paris Musée d’Orsay), an oddly Munchian painting which may be Homer’s most exuberant work, unique for its aura of mysterious freedom. It is one of the last times that women figure in his work in a major way. Two girls dance by the ocean, a last dance of the feminine cast against the blackness of the ocean and a silhouetted crowd of onlookers who are gazing not at the girls’ dance but away from them, toward the moonlit sea. Here, in the girls’ whirling turns, there is a movement independent of ocean and sky, a gratuitous assertion of inner imperatives, an impractical gesture good for nothing at all. A small human explosion in darkness opens up space by sheer force of abandon.

3.

Women don’t disappear all at once. In fact Homer becomes a specialist in depicting them, or at least in depicting a special category: the fishwives of Tynemouth, who watch and wait and mend nets and mostly just endure. In an eighteen-month stay in England, from March 1881 to November 1882, he establishes himself in the North Sea village of Cullercoats, near Tynemouth. He extends the kind of work he had done the previous summer in Gloucester, Massachusetts, by removing to another seacoast which, if not harsher, is certainly more remote, as if to force the exclusion of any subject matter not germane to his chosen course.

He has arrived, according to plan, at a world from which croquet and backgammon, at least, are absent, a world of spray and noise and intermittent darkness. To be cold and wet and tired will henceforth be the normal condition of most of the people he chooses to paint. He puts everything else aside to concentrate on wreckage and rescue and irretrievable loss. By traveling to the likely scenes of disaster (174 Gloucester fishermen were lost at sea in the year Homer worked there) he can count, like a film director selecting a location, on a certain level of violence, as well as on certain stock types of rugged durability and stoic suffering. The “dapper medium-sized man with a watercolour sketching block” who showed up to sketch the wreck of the Iron Crown off the coast of Culler-coats was in his professional element, with a matchless opportunity to study at first hand the shape of catastrophe.

At the edge of everything he comes upon the quintessential nineteenth-century site of contemplation: the sea, angry and implacable, generative and destructive, the sea so hackneyed in its sublimity that it earned an entry in Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas: “SEA—Bottomless.—Image of infinity.—Induces profound thoughts.” It is impossible to say how much if at all Homer was acquainted with the oceanic currents in Coleridge, Poe, Melville, Michelet, Hugo, Loti, Tennyson, or Whitman, but he could hardly have avoided the pervasive metaphorical retailing of calm and storm, reef and warning light, maelstrom and shipwreck and rescue. The beacon in darkness or the fisherman’s prayer or the drowned maiden were commonplaces of balladry and popular illustration: Homer had already contributed to this mythology in his 1873 drawing The Wreck of the “Atlantic,” with its discreetly erotic contemplation of a drowning victim cast up on the rocks.

Out of such material he created the sequence of epic sea dramas—The Life Line (1884), The Herring Net (1885), The Fog Warning (1885), Lost on the Grand Banks (1885), Undertow (1886), Eight Bells (1886), The Signal of Distress (1890–1896)—which represents the culmination of his narrative energies. They are among those visual works which aside from anything else belong to the literature of their era: mute novels, as if Toilers of the Sea or An Iceland Fisherman had been forcibly compressed into a single, massive block.

Two of these paintings (The Life Line and Undertow) involve the rescue of women from the ocean. It is peculiar that his most (his only?) erotically charged paintings of women involve near-death situations. Indeed, the close physical contact in Undertow, a large-scale and (for Homer) almost overwrought canvas, is startling in the context of his other paintings. Nowhere else are his people such giants, almost bigger than the ocean from which two men rescue a pair of unconscious women locked in the deathly embrace of the half-drowned. As for The Life Line, the forcible extraction of the woman from the element that would engulf her is as theatrical a tableau as Homer ever painted: one embrace (of rescuer and rescued) is poised directly above another (of victim and cradling waves ready to receive her), and the intimate embrace of the two human figures is made dreamily remote by the red scarf which carefully obscures the face of the rescuer.

However successful the rescue, the picture’s energy derives from the imminence of engulfment. Homer has calculated the effect almost too knowingly, like a horror movie director savoring a good scare. Elsewhere he goes almost beyond the possibility of vicarious pleasure. Unlike Delacroix’s Massacre at Chios or Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, Homer’s disasters occur in relative isolation, with none of the highly colored splendor of an operatic downfall. If Lost on the Grand Banks and The Gulf Stream are among the most terrifying of paintings, it is because of the indifference of the spaces in which suffering is enclosed. In The Fog Warning the fishing boat is squeezed in the ocean as in a vise, and the line between the foam’s white and the shadowed side of the boat is as sharp as if cut with a knife. That cutting edge of sea against protecting vessel is the painting’s axis, around which the menacing change in lighting gathers.

In its harrowing successor, Lost on the Grand Banks, incipient fog has become engulfing fog and the lost fishermen are lost beyond hope. The scene is of such stark closure that it might be a cautionary panel from some very dark sermon. What, though, would the warning be: Not to fish? Not to live near water, or to live at all? The painting can’t help but evoke the third panel of Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, in which the man in mid-life looks on with terror as his allegorical boat drifts into rough waters, but there is not the slightest suggestion of the distant angel who watches over Cole’s voyager. The fishermen, seen in profile, look directly at death as they take in the blackness advancing across the water, like a blanket in which they are about to be smothered.

There is a basic airlessness in these landscapes, or more precisely an air as massive and implacable as rock. The canvas is a zone of pressure, hemmed in by gravitational force. The wind makes vast unstable trenches in the ocean’s surface. There is no escape from matter; Homer’s figures are under the weather, pinned down by it. Space is as much enclosure as opening. The painting is never a parallel world, never a garden of delight cut loose from contingencies: the same currents exist there as here.

Homer’s painting is never about space for its own sake but about the human figures who inhabit it, even when they are absent. The ocean is ocean seen by a person: a subjective landscape, encompassing only as much as the viewer can grasp in a real instant of time, unlike the panoramic landscape art of the Hudson River school which sprawls in a God’s-eye view of creation, the rolling Cinemascope frames inviting the spectator to roam for hours among meticulous details.

Homer’s figures are inserted or interpolated into force fields. They submit calmly to their fate, like the men descending into the wave’s trench in Kissing the Moon (1904), perfectly upright although all but their heads is invisible within the trough. Landscape for Homer is a mise en scène in which the scene itself is subject to sudden catastrophic change. His sea paintings are monumental representations of precariousness. Even the benign Breezing Up (1876) contrasts the potentially murderous force of the ocean and the relative powerlessness of the passengers.

His old habit of rearranging stock figures in different settings, while it may have arisen in response to the practical imperatives of the illustration business, suggests something like a hidden philosophy. Places are given meaning by human presence, yet the humans are for the most part interchangeable and devoid of individuality. How well do we know any of these people? Their expressions have little to tell. The stance is everything. He gives us figures, not faces: the face of the rescuer in The Life Line is concealed completely, and in Right and Left (1909) the shoulders and head of the hunter in the boat are hidden by the flash and smoke of the shot that has killed the ducks who fall through the foreground. The hunter amounts to nothing but his action, an action identical to the death of the two fowl.

Even the fisherwomen of Cullercoats and the Adirondack guides are types. Homer’s people—even his most physically active figures—have an essential resignation. The rough-hewn guides and hunters of the Adirondacks pictures are certainly doers, but they do only what they have been, so to speak, programmed to do; their future actions are utterly predictable and in a sense mindless. They will go where they have gone before, go through the same motions. Their only real choice is how they will respond to circumstances they can do little to avert.

That response embodies a certain professionalism, ultimately a kind of calm, sober, grave manliness. It is a manliness that can be hard to distinguish outwardly, as with his Adirondack deer hunters, from inarticulate brutishness. Homer uses the most delicate watercolor techniques to show (as in The Fallen Deer of 1982) the Adirondacks as a killing ground; the art historians would have us believe that these pictures are intended as a protest against brutality, but I suspect they are more an acknowledgment, purposely neutral, of its existence. As far as the world is concerned he executes a job of work, and it is not their business to know more than that.

Even the terror with which the fishermen confront their approaching doom in Lost on the Grand Banks has a practiced air about it; to ready themselves for such a fate was part of their training. If Homer abandoned urban civility and ornament, it was to render a toughness as male and American as antlers over the mantelpiece or the odors peculiar to an abandoned fishing lodge. His contemporaries recognized the gesture, and applauded his freedom from everything “namby pamby” and vaguely European.

We in turn can recognize a relation between these wilderness guides and hunters and the no-nonsense men in the films of Howard Hawks (Tiger Shark or Red River or The Big Sky). Homer himself might be such a character, given over to a job of work which occupies him from first to last: “There is certainly some strange power that has some overlook on me and directing my life,” he writes to his brother in 1899. “That I am in the right place at present there is no doubt about, as I have found something interesting to work at, in my own field, and time and place and material in which to do it.”

Homer is indeed “frustratingly reticent”: but what do the historians want him to say? What words would resolve whatever problem is created by his deliberate silence? Is it possible to imagine a verbal formula that would neatly impart “meaning” to his final paintings of the sea, or for that matter any of the others? His silence is his statement. He ends by painting situations where speech would be inappropriate or impossible, where words would startle the fish or be drowned out by breakers, or—in Lost on the Grand Banks or The Gulf Stream—where any form of verbal appeal would be utterly useless. These are not paintings of comfort, either material or spiritual.

Never more so than in Fox Hunt (1893), where the endangered protagonist—a weakened fox beleaguered in snowdrifts by a flock of predatory crows—is incapable of speech. In its sense of stark deprivation and animal cruelty the painting inhabits the same world of wintry allegory as certain medieval poets, such as Langland or Henryson. The horizontal composition—we hover over the events much as the crows hover over their imminent victim—seems to crush the fox between the white band of snow and the dark upper strip of ocean and darkened sky. The speechless fox is also faceless—we are not even granted as much communication as he might make with his eyes, which are turned completely away from the viewer and toward the ocean.

This Issue

February 29, 1996