1.

The imagery of triumph and even comedy that attended the events of August 1991 in Russia comforted, and ultimately deceived, the world. The men of the Communist Party, the Army, and the KGB who had tried to seize power in the name of Leninist principles and imperial preservation betrayed their weakness before the cameras: their hands trembled, they drank themselves senseless, they could not bear to pull the trigger (except in the case of one conspirator, Interior Affairs minister Boris Pugo, who, when all was lost, shot his wife, then himself).

The images of Soviet collapse were as vivid as any imagined in Eisenstein’s October. On the night the coup failed, the statue of the founder of the secret police, Feliks Dzerzhinsky, dangled from a crane, as if from a noose, outside the offices of the KGB. Aides loyal to Boris Yeltsin roamed the halls of the Central Committee, giddy and wild, searching for files and cash, the detritus of the old regime.

After Mikhail Gorbachev returned to Moscow from his house arrest in the Crimea, he tried, if only for a day, to speak up for the Party, but after one of his closest aides, Aleksandr Yakovlev, made it clear to him that trying to rescue the Party was tantamount to “serving tea to a corpse,” Gorbachev resigned as general secretary, dissolved the Central Committee, and, it seemed, put an end to the claque of Bolshevism once and for all. “The Party Is Over” was the headline dreamed up on a hundred different copy desks around the world.

The imagery of historical closure and beginning was everywhere and irresistible. Four months after the August melodrama, on the night of Christ’s birth, Gorbachev resigned, handing over his nuclear baggage to the leader of a new state with a new flag and new symbols. The red banner of the Bolsheviks was lowered from the Kremlin staffs for the last time. The red, white, and blue tricolor from the Kerensky years flew in its place. Lenin’s face disappeared from the ruble (though it did show up on T-shirts advertising the latest McDonald’s). For weeks CNN, the photographers—all of us in the press—had a field day.

The truly sly men of the Communist Party did not wait around for the cataclysm. They had long since transformed themselves into biznesmeni or konsultanti; they used their web of connections to cash in, to position themselves for what would obviously be the biggest privatization and land grab program in history. There were many ways to get rich; nearly all of them depended on some kind of connection to state power.

Men like Boris Gidaspov, a Leningrad Party chief who had made his name in the late 1980s with an ardent defense of orthodox principles in the face of Gorbachev’s heresies, seemed to disappear for a while and then reemerged in a thousand-dollar suit. By 1995, I had not heard of or seen Gidaspov for years. One afternoon at Pulkovo airport in St. Petersburg, I saw him getting off the plane from Moscow. I caught up to him and introduced myself, and we chatted a while. Then he begged off, saying, “I’ve got to go. Meetings downtown. You know how it is.” As he walked away, Gidaspov clicked open a cellular phone and then ducked into a waiting limousine, a rather sleeker version of his old Party model. I wondered who was paying the bill this time. Gidaspov, it turned out, was president and chairman of a local corporation called TechnoChem.

Gidaspov was a representative man. In the years following the collapse of the Party, interests, rather than ideas, dominated the political scene and the obsessions of nearly all Russian politicians. The old nomenklatura did not so much give up power as scurry around trying to find their place and privileges on the new map of influence. With the collapse of the central planning system and the authority of Moscow, a Party chieftain in a distant place like Vladivostok could, with the right amount of guile and cooperation with local mafias, transform himself into a baron. Former Party men quickly got into the oil business, the natural gas business, the gold and diamonds business; they started banks, commodities exchanges, and dozens of other enterprises—all of which operated in an atmosphere of virtual lawlessness.

While all this was happening, a small corps of devout Communists, enraged by what they saw as Gorbachev’s betrayal and the collapse of a glorious empire, refused to swim with the rest. In 1992, less than a year after the coup, they went to the Constitutional Court to fight the Yeltsin government’s edict that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (the CPSU) was illegal; a parade of functionaries went to court to speak up for the Party’s history. One Party representative, Dmitry Stepanov, said that more people had been killed in traffic accidents than by Stalin’s executioners. The Party, he said, would use “the same methods” to get back into power as the leaders of the August coup. No one took him very seriously. Yeltsin controlled the tanks now. (In Moscow and later in Chechnya he would prove himself all too prepared to use them.) The trial ended with just a few people in the courtroom and no one paying much attention. The Party, the Court ruled, could operate on a local basis only. Even the Yeltsin forces did not mind: their greatest concern was with the opposition in the parliament and with the unstable but dangerously popular leader of the Liberal Democratic Party, Vladimir Zhirinovsky.

Advertisement

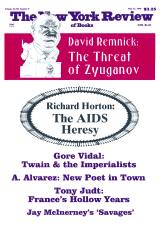

One of the men in the courtroom who had testified for the Party, an officer in the Central Committee’s ideological department named Gennady Zyuganov, left the building promising that he and his comrades would return, and, when they did, a red flag would be flying once more over the Kremlin towers. It is four years later, and the odds are about even that Zyuganov will make good on his promise. He will not require tanks. In the June elections, the first democratic transfer of power in a thousand years of Russian history could result in the elevation of the leader of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation. This is a far more chilling prospect than most analysts—the White House included—seem to believe.

2.

In Moscow and in the Western press, the conventional notion of Zyuganov is that he is a colorless, none too intelligent apparatchik whose sole talent is to make himself appear to be the sort of unthreatening Communist that the audience in question is willing to accept. When he travels to the West, talking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, or on Larry King Live, he professes to be a social democrat, a kind of Russian Olof Palme, who would not dare to renationalize properties and industries for fear of upsetting the civil peace. He sounds in the West like one who puts the social security of his constituents above all, rather like a Moscow representative of the American Association of Retired People. At a meeting with a newspaper editorial board in the United States, one editor asked him why, if he was such a social democrat, he called his party “communist,” Zyuganov said that for reasons of tradition in Russia, ” ‘communist’ is a good brand name.”

But among urban pensioners and unemployed workers and in the poor conservative provinces of the Russian glubinka, the deep countryside, Zyuganov plays on people’s deepest suspicions, encouraging them to believe that Stalin was, in fact, a heroic patriot; Gorbachev and Yeltsin were guilty of treason, and the United States is the culprit for all that is wrong in their lives. To the tremendous cheers of the crowd (a sound Yeltsin has not heard in a very long time), Zyuganov promises the restoration of the Soviet Union and the demise of an arrogant and corrupted West.

Zyuganov’s support is generally among voters who have fared badly since the economic and social earthquake of 1991. He is understandably popular among those who have been unable to adjust to the collapse of the old patriarchal state and its social welfare system, who are enraged by the new disparity between rich and poor, and bewildered by the sudden loss of Soviet power and identity. Even among some liberal intellectuals, hatred of Yeltsin has grown so intense that the Communist leader seems relatively appealing. Andrei Sinyavsky, who was jailed under Khrushchev and Brezhnev, has accepted the idea that Zyuganov is the lesser of evils. “I don’t think Zyuganov will begin to reanimate Communism,” Sinyavsky told an interviewer for the newspaper Argumenti i Fakti. “In the first place, the West will not give one kopeck…. Second, the people have gotten smarter. Probably this will be something of the social-democratic orientation. It seems to me that we can expect something better from Zyuganov.”

Gennady Andreyevich Zyuganov was born in 1944 in the tiny village of Mimrino in provincial Russia. “I was born in the seventh month, like Churchill,” he has said. “That’s under the sign of Cancer. But if I had been carried to term, to nine months, I would have been a Leo. Therefore I am a Cancer with pretenses toward Leo.” The closest city to Zyuganov’s village was Oryol, Turgenev’s city and the scene of horrendous fighting in World War II. Zyuganov’s parents survived the war years and they both earned their living as schoolteachers. In fact, his mother, a notably strict teacher in the local rural school, had Gennady as a pupil and, one magazine informs us, the boy dared call her “mama” just once.

Advertisement

At the urging of his instructors, Zyuganov set out to be a teacher of science and mathematics. In the army in the mid-1960s, Zyuganov served in Germany and the Urals and worked with intelligence forces concerned with chemical warfare. Like many of his army mates, he joined the Communist Party while in the service. After moving back to Oryol, Zyuganov was asked to go into Party work, and he began, like thousands of officials before him, as a Komsomol officer. He worked his way up the Komsomol ranks and then the ranks of the regional Party organization but showed no great brilliance. Compared to stars of his generation, like Gorbachev, Zyuganov’s advancements were not especially fast, nor was he particularly distinguished. He was finally called to Moscow in 1983 to work as an instructor in the department of propaganda, a relatively junior post. In 1989, he became vice-chairman of the ideology department; he became, in other words; a priest of an orthodoxy that was two years away from death. In fact, by the time Zyuganov arrived, the department had broken down almost entirely. Its product, communist ideology, was not in much demand—not even by the general secretary.

Zyuganov first came to the attention of Russians in the late 1980s when it became possible for Central Committee officials to get up at meetings and give speeches accusing Gorbachev and his circle of betraying “the great Leninist ideas.” Zyuganov joined those voices who began calling on Gorbachev to step down as general secretary and he stood out especially as a public enemy of Gorbachev’s top liberal aide, Yakovlev. In what would become a staple of Party papers for years to come, Zyuganov wrote a scathing article in Sovetskaya Rossiya implying that Yakovlev, who had studied for a year at Columbia as a young man, was an American “agent of influence,” trained by American agents to rise high in the Soviet bureaucracy and undermine the state.

Like most orthodox Communists who were disenchanted (or worse) with Gorbachev, Zyuganov helped form in 1990 a separate Communist party based in Russia, distinct from the CPSU. As a member of the new party’s Politburo, Zyuganov was instrumental in working out new ideas that would bridge the ideological gaps between and among traditional Leninists, monarchists, nationalists, and even neo-fascists. That the old ideology of purist Marxism-Leninism had been discredited was obvious even to these Party nomenklatura. These new ideologues began to jettison talk of “the dictatorship of the proletariat” and replace it with the “greatness of the Russian state”; they evoked tsarist warriors more than Bolshevik founders.

In the summer of 1991, with Gorbachev working with Yeltsin and other republican presidents to reshape and decentralize the Soviet Union, Zyuganov and a group of other leading conservatives in the military and the Party decided to publish a manifesto of resistance, a call to arms of “all patriots.” On July 23, Sovetskaya Rossiya published “Slovo k Narodu” (“A Word to the People”): “Our Motherland, this country, this great state which history, Nature, and our predecessors willed us to save, is dying, breaking apart and plunging into darkness and nothingness…. What has become of us, brothers?… Our home is already burning to the ground…the bones of the people are being ground up and the backbone of Russia snapped in two.” The Communist Party has given over its power to

frivolous and clumsy parliamentarians who have set us against each other and brought into force thousands of stillborn laws, of which only those function that enslave the people and divide the tormented body of the country into portions…. How is it that we have let people come to power who have no love for their country, who kowtow to foreign patrons and seek advice and blessings abroad?

The statement appealed directly to the military to close ranks around all patriots who could not tolerate what Gorbachev and Yeltsin were preparing to do to their country. In Moscow, journalists and politicians considered “A Word to the People” to be a warning of an imminent coup. Three weeks later, the tanks rolled down Kutuzovsky Prospekt.

Three of the signers of “A Word to the People” were directly involved in the coup. Zyuganov was not among them. The coup plotters were at a much higher level. In a biography of the former Russian vice-president, Aleksandr Rutskoi, Zyuganov recounts how, early on the morning of August 19, a friend called him at home and said there had been a coup.

“Where?” Zyuganov said. “In Bolivia?”

After the defeat of the coup and Gorbachev’s dissolution of the Central Committee, Yeltsin firmly believed that he had defeated the Communist Party once and for all. In an address before the US Senate, he announced the end of communism. In fact, he banned the Party entirely under the pretext that the CPSU was never a party the way the rest of the world understands the word but rather a political organization “of a special type,” as Lenin put it, which had unchallenged and absolute control over every aspect of the public lives of its subjects.

In the meantime, however, the Yeltsin government decided it was unnecessary to try to put forward an ideology, a national idea, to replace the old one. The largely unspoken understanding in the first years of the Yeltsin era was that the new Russia would be more or less democratic, more or less market-oriented—in other words, more or less like the United States, Western Europe, or Japan. Russia, in other words, had abandoned not only the Marxism-Leninism of the twentieth century, but also the Slavophile notion of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that declared for Russia a “special role” in the world, a degree of particularity and messianism that set it off from all other nations. Russia, a Eurasian state, would now lean westward. Yegor Gaidar, Yeltsin’s economic guru, was a disciple of Hayek, Friedman, and Smith; democracy could not exist without private property and free markets. Yeltsin’s foreign minister, Andrei Kozyrev, was fluent in English and French and struck up as good a relationship with his American and European co-equals as any other foreign minister in Russian history. In a book published in 1994, while he was still in office, Kozyrev quoted one Westernizer after another, practically begging his countrymen “to end the traditional isolation” of Russia and the Soviet Union from the rest of the world and warning of “partisans of an imperial policy” who would, once more, come to power under a banner of furious xenophobia.

As recently as 1995, I asked one of Yeltsin’s main political advisers, Giorgi Satarov, why Yeltsin himself had not done more to promote, even loosely, the sort of ideas Gaidar and Kozyrev were advertising. Why hadn’t Yeltsin gone beyond economics and foreign policy to help shape an identity for this essentially newborn state?

“When totalitarianism was being destroyed, the idea of ideology was being destroyed, too,” Satarov said. “The idea was formed that a national idea is a bad thing. But the baby was thrown out with the bath water. Our Kremlin polls show that people miss this. In 1989, 1990, and 1991 there was a real sense of mission to destroy communism. After that seemed to be resolved, there was a vacuum that followed. Partly this is why the Communists are doing well today.”

If Yeltsin ever believed in democratic principles, he had lost an opportunity. “The essential national drama is the search for identity and in this we, the liberal intellectuals, have failed,” a prominent literary historian, Andrei Zorin, told me recently in Moscow. “There is no sense of what this new country, Russia, really is. This was a pressing intellectual obligation. It should be an exciting intellectual adventure to start a country. Look at France after the Revolution, you had everyone going at it from the ultraconservative De Maistre to Madame de Staël. Or in eighteenth-century Britain, after the Glorious Revolution, there was Locke and the rest. And this was done over time in the United States as well. These last four or five years in Russia have produced little besides pure hysteria. The Gaidar government, in this regard, was too technocratic. They were anti-Marxist but still held the Marxist idea that the economy decides everything. The one symbol we might have had—the White House in 1991—was promptly lost in 1993” when the army was ordered to fire on the building.

In 1992, the Constitutional Court ruled that while the Russian government would inherit the property owned by the old CPSU, Communists were free to begin parties on a local and regional level. This was precisely the organizational opening that the remaining true believers needed. The men, like Zyuganov, who had not gone off into business or joined with the new Kremlin power began forming organizations, parties, and alliances in the open. In February 1993, Zyuganov was elected chairman of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, one of many Communist parties. Largely because of his organizational skills, his ability to bring into the fold countless provincial pols who yearned for the old structures, he was able to make the CPRF into the dominant leftwing party. The party now has about 560,000 members—tiny compared to the 20 million of the old CPSU—but gigantic compared to any other party in the 1996 elections. Yeltsin, for one, has no political party at all—one of his greatest oversights.

From the start, Zyuganov began to hint at the sort of ideologically hybrid party he was creating. “Now a new sort of party is being born,” he said. “Much is being taken from the past: solidarity, social justice, and great spirituality. The Party should also take in Russian patriotism, love of one’s Fatherland, and an interest in Russian power.” Zyuganov’s turn is rooted in the same cynical political motives that motivated Stalin, on the eve of the war, to invoke Aleksandr Nevsky, Dmitri Donskoi, and the Orthodox Church.

In addition to building up his own party, Zyuganov also began to join forces with far-right nationalists, setting off talk of a “Red-Brown coalition.” Acting as the chief Red, Zyuganov became chairman of the co-ordinating council of the people’s Patriotic Front of Russia, and a leader of the National Salvation Front, a group that included Bolsheviks, fascists, and a general of the KGB. The most important aspect of his increasing association with the nationalists was the way the experience rubbed off on Zyuganov’s ideas. He began to develop his eclectic ideology, drawing on whatever was still appealing in Soviet history and ideology but also borrowing from whatever sources from the pre-Soviet era that seemed appropriate and potentially popular. What Zyuganov has managed to do is create a potent ideology that cynically combines the seemingly uncombinable; perhaps that is what he means by “the usefulness of the dialectic.” The strangeness of this enterprise was nicely symbolized at meetings at which there were two flags in evidence—the red Soviet banner, and the black, yellow, and gold of the tsarist era—thus reconciling the enemies of the civil war. Add to that a few black-shirted neo-Nazis guarding the podium and you begin to get a sense of these meetings and the new wave in general.

The best known of Zyuganov’s ideological mentors in this project is Aleksandr Prokhanov, a newspaper editor and novelist whose work was so celebratory of the military in Afghanistan that he has long been known as “the nightingale of the General Staff.” Prokhanov is a descendant of the Molkane (or milk-drinkers), one of the Russian Orthodox groups that were nearly wiped out under Soviet power. The newspaper he publishes—first there was Dyen (The Day), and now Zavtra (Tomorrow)—is printed monthly on cheap paper and features apocalyptic cartoons (usually of a Yeltsin figure, made grotesque and murderous), headlines reminiscent of the New York Post, and endless screeds in tiny, bleeding type. The paper predicts civil war with chemical and/or nuclear weapons on a regular basis; Yeltsin’s government is referred to as an “occupier” and Yeltsin himself as “EBN,” an anagram of his initials which also recalls the word yebena, a variation on “fuck.” There is enough slander, bile, and anti-Semitism in Zavtra to fill an issue of Der Stürmer. Prokhanov was first aligned with the “village writers,” men like Valentin Rasputin and Vasily Belov, who have written, often well, about the degradation of the countryside and provincial ways of life. Prokhanov made his name with his banner-waving war novels A Tree in Kabul and Nuclear Shield and then, in the Yeltsin era, with his newspapers.

Like so many of the new extremists, Prokhanov is perfectly willing to perform his role as the heavy. He is not shy about inviting visiting Westerners to his office and describing for them precisely why they represent Satan. Not long ago, some Washington Post reporters took Ben Bradlee and Katharine Graham to see Prokhanov as part of their political tour of Moscow; after Prokhanov delivered his usual fire and brimstone, complete with a few choice cracks about Zionist influences, he left the room to take care of some newspaper business. Bradlec, in his boredom, reached over to a dish of candy. “Don’t touch it, Ben,” said Katharine Graham. “It’s probably poisoned.”

But unlike some of his comrades, Prokhanov is neither insane nor beyond self-analysis. If one journalist in Moscow has accurately predicted the development of the myriad anti-Yeltsin forces between 1991 and 1996, it has been Prokhanov. In Zavtra, Prokhanov has printed interviews with and articles by the seemingly irreconcilable: “maximalist” Communists like Viktor Anpilov; crackpot military men like Colonel Viktor Alksnis, General Valentin Varennikov, and General Albert Makashov; the anti-Semitic nationalist and world-class mathematician Igor Shafarevich; village writers like Rasputin and Belov. The paper is filled with racists, militarists, and loons of all varieties. In an attempt to establish a Turkic-Slav alliance, Prokhanov frequently runs the articles of eccentric imams and priests. Zyuganov doesn’t mind the company.

Prokhanov calls Zavtra the “newspaper of the spiritual opposition.” It is hard to find in Moscow and nearly invisible outside the capital. But despite the tiny circulation, Prokhanov has used the paper as a way for opposition forces to read one another; on the pages of Zavtra percolates an extremely potent brew. What energizes Prokhanov and unites every voice in his paper has nothing to do with nostalgia for Marx or Lenin, but rather an intense longing for empire. Above all, these voices are gosudarsveniki, statists; they mourn for a lost empire and are determined to rebuild it. Prokhanov’s deputy editor, Vladimir Bondarenko, once told me after he had made a trip to the United States that while David Duke’s views might be a bit extreme, he did feel in ideological synch with Pat Buchanan; Bondarenko is now one of Zyuganov’s policy advisers. After years of searching, Prokhanov has found the proper vehicle for his message: Gennady Zyuganov.

3.

Zyuganov is fifty-one, the father of two daughters. He is portly and bald and speaks in the drone of old Soviet newscasts. He is dismal on television. In most things, Zyuganov affects a Leninist modesty and sobriety. When an interviewer compliments him on the cut and cloth of his suit, he protests that it is not foreign-made, but rather the product of a Russian shop inside GUM, the huge shopping center on Red Square. When he is asked how he celebrated winning his doctoral degree in 1995, he says, well, of course there was a party, “but no caviar.” Nor does he drink too much, he is fast to remind the voters grown weary of Yeltsin’s well-publicized benders. “I’m not against a good glass of wine or a little shot of vodka,” he says. “But I drink quite modestly. I can’t handle more than three vodkas. Someone has to be sober among today’s politicians.”

Zyuganov is comically vain about his intellectual range. Although he started out in the sciences, he won his advanced degree in 1995 in matters closer to the affairs of state. “My specialty is a rare one: political philosophy,” he says. “I got my doctorate with a thesis on the fate of Russia in the world in the coming decades.” At Moscow State University, he defended his dissertation on Russia and the modern world in front of a panel of like-minded professors, many of whom even now boast Marxism-Leninism as their academic specialty. In speeches and interviews, Zyuganov will brag of having read “all the philosophers.” He does know the names of many of them.

In the three books Zyuganov has published in the past few years, he unleashes a torrent of these names, and the names one might expect (Marx, Lenin, Engels, etc.) do not enjoy pride of place. Zyuganov, after all, is out to remake, not restate, the ideology of his party. He has even added to the party symbol; the Communists are now represented by an insignia of the hammer, sickle, and book.

Zyuganov’s first scholastic task was to put forward a version of the Party’s history that was believable enough to a majority of the Russian electorate. Ever since Gorbachev reopened the debate on Soviet history in 1987, conservatives in the Party have railed against the “blackening” of the Party and its past leaders. By the time the criticism reached the sacred hem of Lenin it was clear that the attempt to reform the old regime had been overtaken by a movement to destroy it entirely. In a speech called “Twelve Lessons of History” delivered last year on the anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution, Zyuganov claimed that Gorbachev had set off an orgy of “libel” against history and that the Yeltsin regime had so thoroughly distorted a glorious Russian and Soviet past that it was no longer possible to read about Tolstoy, much less 1917, in new textbooks.

This is rubbish, of course, but adherence to fact is not what Zyuganov-ism is about. On a recent campaign trip to Siberia, Zyuganov gave a speech on the various evils of foreign invaders of the West and compared them to the Nazis, who, he said, had been ordered to replace Orthodox churches with Protestant churches. When Alessandra Stanley of The New York Times questioned that piece of history, Zyuganov’s spokesman allowed that the candidate had permitted himself some “poetic license.” It is his custom to flash that license often.

Zyuganov, as the leader of the Party’s restoration, rejects any notion that Leninism represented a break either with Russian history or with an international lineage of humanistic thought.

The entire planet, all educated people well understand that Lenin is one of the great political figures and thinkers of modern times. In his nearly fifty-four years, he wrote, more or less, a collected works of fifty volumes and is a presence in every library in the world. His work is studied everywhere. He had one of the great minds of the epoch and what he wrote remains relevant today. Take, for example, his work on the theory of imperialism: Today we see how this pertains to what is happening with transnational corporations….

Needless to say, Lenin’s brutality—his assault on the peasantry, his war on the church and the intelligentsia, his establishment of the first labor camps on Solovetsky Island—are not part of the portrait. Rather, for Zyuganov, Leninism drew on “the greatest ideas in the history of humanism: brotherhood, justice…. These were not the ideas of seventy-five years but of thousands of years…. Buddha, Jesus Christ, Mohammed, Mahatma Gandhi, Lenin: they are all of the highest moral order, champions of the fellowship among men, and therefore the vast majority of people go for them.”

Zyuganov determines that there were actually two Communist Parties: the party of heroic men like Stakhanov, the legendary worker, and Kurchatov, the legendary scientist, Marshal Zhukov, and Yuri Gagarin. And then there was the party of “betrayers”: Yezhov and Beria, Trotsky and Yakovlev, Gorbachev and Yeltsin. As leaders of the secret police, Yezhov and Beria were guilty of tremendous cruelty; Gorbachev and Yeltsin “sold out” the Party and the empire, all under the influence of a rapacious West and the West’s “agents of influence.”

Zyuganov defends one of the traditional whipping posts of anti-Soviet dissent: the enormous and privileged nomenklatura that ran the country. “The qualified apparat served the Soviet state well for three quarters of a century,” he writes. “There were mistakes…but this nomenklatura all the same created and supported a great and powerful state.” The apparatchiks, then, are in the party of the good. Here, of course, Zyuganov is not only defending his own species; he also knows that there are millions of old apparatchiks still around today, and they all have families, and they all vote.

But where, one might ask, is Stalin in Zyuganov’s “two party” system? In speech after speech, Zyuganov rejects any notion that tens of millions of Soviet citizens were destroyed under Stalin. He claims special access to the archives, and these show, he insists, that only about a half million people were killed under Stalin “and most of them were Party members.” Zyuganov’s numbers, of course, contradict by tens of millions every reputable scholar in the field, Russian and Western.

Stalin, despite all the contrary evidence, is also credited as a great military leader in the war, and thus the savior of humanity from Nazism. Zyuganov could not reach the poll numbers he now enjoys with the support solely of the older Russians who still believe in the goodness of the Generalissimo or the even smaller percentage who carry his portrait at Communist Party rallies. Zyuganov does not risk his chance at broader support by openly speaking out in favor of Stalin. But he does have the occasional nice thing to say. In fact, Zyuganov sees in Stalin a wise ideologist, one who tried to combine imperial pride with Communist ideology. Stalin, he writes, “understood the urgent necessity of harmonizing new realities with a centuries-long Russian tradition.” Stalin was a true “patriot”—a “national Bolshevik”—who “understood the special destiny of the country, while Khrushchev was oriented toward crude consumerism.” If Stalin, who ruled from 1927 to 1953, had only lived “a few more years,” he would have “restored Russia and saved it from the cosmopolitans.”

Zyuganov, of course, is referring to Jews. In fact, if Stalin had lived, the Doctor’s Plot prosecution would have continued apace, as would the expected attempt to purge Russian Jewry.

Zyuganov also claims that Stalin, who had obliterated the peasantry in Ukraine and southern Russia through forced collectivization and artificial famine, was bound to have made life good again for the farmers on the kolkhoz. “You know, I am acquainted with the documents,” Zyuganov told an interviewer, “and I was shocked when Stalin, not long before his death, said we are obliged to return our debt to the peasantry.”

This cynicism about Soviet history is not peculiar to the top leader of the new Communist Party. Not long ago, I met with Igor Bratishchev, one of Zyuganov’s closest allies in the Duma. Bratishchev would no doubt win a high post in a Zyuganov government. His willful and convenient forgetfulness, his ability to rearrange history, is typical of his party. When I asked him about Stalin, he wanted it all ways. Stalin was a “great general” who “saved the world,” Bratishchev said.

Five minutes later he was saying,

And as for Stalin and those who did terrible things, they were not Communists. They carried Party membership cards. This is true. But anyone can enter a church holding a candle. That doesn’t make him a believer, does it? We see Yeltsin in churches but do you really think he’s a believer? If there were repressions, they were organized by people, not Communists, and they were directed, first and foremost, against Communists. The only real privilege of being Communist was to lead your brigade into battle and then to work in an atmosphere of self-denial. For example, you are writing this to make money, and I am giving this interview for free.

“If there were repressions…” To parse such a statement is to begin to give it credit.

Zyuganov’s telling of Communist Party history features a turn from celebration to repugnance quite early in the Party chronology. Khrushchev represents a period of “unnecessary” reforms and vulgar consumerism. Brezhnev’s era was sclerotic and overlooked the urgent need to modernize the economy. Gorbachev, of course, sold out the country and the Party entirely simply to hear his name chanted in the capitals of Western Europe and the United States.

The only post-Stalin leader admired by Zyuganov and the new Communists is Yuri Andropov. Zyuganov has a difficult time forgiving Andropov for playing the mentor to Gorbachev, but he compliments his intelligence, his relative modesty, and, above all, his discipline and commitment to the Soviet Union as a great power. Andropov’s reign in office lasted little more than a year, and there are many Communists in Russia today who are convinced that the only thing that separated the empire from oblivion was Andropov’s failed kidneys.

As chief of the KGB, Andropov helped lead the Soviet assault on Prague in 1968 and a general war on dissidents at home. Zyuganov, especially when he is in the West, promises he would never clamp down on dissenting opinion, but it is clear that he has no argument with the old methods. He greatly admires the Chinese model of reform and wishes “we had taken the advice” of the Chinese Communist Party leadership when they warned Gorbachev about taking glasnost too far. And as far as the events at Tiananmen Square are concerned, the Chinese powers did what was necessary, though it was a “difficult” situation. “I can’t imagine what would happen here if such a situation took place.” The West, in its sanctimony and self-interest, makes too much of its notion of human rights. “In our time, we had three hundred or so dissidents, and there was endless noise about them everywhere,” Zyuganov writes. “But today there are six million refugees in Russia. Our countrymen in the Baltic are treated as second-class citizens. Every other working man in Russia is not paid on time. Who of these patented democrats is speaking out in their interest?”

4.

Zyuganov’s ideological sleight-of-hand has been to graft on to a left-wing party an enormous degree of old-fashioned Russian nationalism. This is not an entirely new trick (as Stalin showed during the war) but in the current context of Russian politics it has an ominous significance that very few have noticed.

Zyuganov’s nationalist evolution is not without deep roots in Party history. In the Brezhnev years, most foreign diplomats, politicians, and scholars understood the Communist Party as a monolith, unshakable in its power and resolve, and utterly united and disciplined in its adherence to orthodox principles. Brezhnev’s ideologist, the “gray cardinal” Mikhail Suslov, was thought to be in absolute charge of his province; there could be no dissent, especially in the top Party ranks or in the pages of the official newspapers, magazines, and “thick” journals.

In fact, there was great division within the Party, though it required tremendous attention to find it. It now seems self-evident that there was a significant cadre of aides and officials in the Sixties who were sympathetic to a Dubcek-style reform, “socialism with a human face.” Gorbachev himself had been close friends in university days with a young Czech named Zdenek Mlynar, who later became one of the top officials in the Dubcek government. When Gorbachev assumed power he surrounded himself with shestidyesatniki, men and women of the Sixties generation who had been deeply affected by the Prague Spring but who had continued working within official structures.

What is less well known is that there were also officials within the Party who were interested in Russian nationalism. The Soviet myth was one of internationalism, “the friendship of peoples,” but the nationalist strain in the Party made little secret of its belief that Sovietism was, at its root, a Russian project, an imperial matter with a red gloss. In April 1968, the journal Molodaya Gvardia (Young Guard) published a few articles which attacked Western-leaning intellectuals inside and outside the Party; such thinking was anathema to the “Russian national spirit.” Those articles were answered first by Novy Mir and then, more dramatically, in October 1972, by a Central Committee propagandist named Aleksandr Yakovlev. In a long article titled “Against Anti-Historicism,” Yakovlev used the ritual wooden language of Party newspeak to condemn the nationalists and their romanticized vision of prerevolutionary, imperial Russia; he criticized them for creating a “cult of the patriarchal peasantry.” Yakovlev must have been sanctioned to write his piece, but he must also have offended someone in the Politburo. He was made a virtual exile for the next ten years—“sentenced” to serving as ambassador to Canada. It took Gorbachev to bring him back to Moscow.

To this day it is a mystery who gave the Molodaya Gvardia writers permission to launch their nationalist campaign and who might have taken offense at Yakovlev’s retort. A rather eccentric, but sometimes prescient, émigré scholar, Aleksandr Yanov, writes in a new book—Poslye Yeltsinsa (“After Yeltsin”)—that it was Andropov. (Yanov, writing in Moscow News, also proposes the theory that Zyuganov, having traded in his orthodox Marxism for nationalism, is poised to play the bloody role of a Russian Slobodan Milosevic.)

Zyuganov’s Communist-nationalist ideology is as rife with ugly conspiracy fantasies as anything found in the works of Pat Robertson, as filled with bogus mists-in-the-forest Wagnerian mythology as early Nazi primers. This kind of stuff has been floating around for years in Moscow—various political extremists are always holding open public meetings and you can always buy an armful of bizarre papers and magazines from various eccentrics outside the Lenin Museum on fair weather afternoons—but now Zyuganov’s lead in the polls makes it seem horrifying. The former prime minister, Yegor Gaidar, wrote recently in the weekly magazine Novoye Vremya (New Times) that if one simply changes the word “Germanic” for “Slavic” in Zyuganov’s work, “everything will be clear.”

“I am convinced,” Gaidar wrote,

that today’s Communist Party of the Russian Federation is not communist but rather national-socialist. The seriousness of the possible threat of their coming power does not consist in just massive renationalization, but rather in populist and military adventures and the practically in escapable move to destroying the already fragile market instruments in Russia.

The threat of a remilitarized economy and a Soviet-era KGB is “not propaganda, but rather part of their worldview.”

Zyuganov’s books are numbingly repetitious and fairly easy to summarize: an empire, led by a “special” civilization, has been betrayed. It is the duty of a united front of patriotic forces to rebuild it. The West has undercut us at every turn, expanding its imperial hegemony over the rest of humanity. Only Russia has the might and the resources and the will to challenge the West and provide balance in the world. The choice Russians face (in this election) is among three variants: a “worldwide” version of Chechen-Yugoslavian unrest; a Colombian-style criminal dictatorship; or a powerful and stable state with structures amenable not to the West but to Russian traditions. A Yeltsin victory will provide the first two options, Zyuganov the third.

“The struggle between the anti-people forces and the patriotic forces is reaching its decisive phase,” he writes. “The outcome of the struggle will decide the future of the country, its unity and values, its independence and authority, its life and the fate of millions of citizens.”

When Zyuganov shifts into his nationalist mode, we no longer hear much about Lenin. Suddenly, a Party chief is quoting Toynbee and Spengler on the decline of the West. He celebrates nineteenth-century Russian reactionaries like Nikolai Danielevsky, whose major work, Russia and Europe (1869), describes the Russians as “chosen people” who are bound to prevail over the corrupted West. Danielevsky was convinced that Russia must reject Western models—parliaments, presidents, etc.—and develop only those traditions that are inherently Russian; in the end, he wrote, Russia would prevail in an apocalyptic battle with the West. Zyuganov, too, talks of the “millennium-long” struggle between the Orthodox and Catholic worlds that began with the great schism of 1054. He, too, intends to prevail.

For Zyuganov, as with all nationalists, Russia is a special case, a “special world,” a “special type of civilization” based on “collectivism, unity, statehood, and the aspiration to attain the highest ideals of good and justice.” Russia, he writes, is hostile in its soul to the West, which is infected with “extreme individualism, militant soullessness, religious indifference, adherence to mass culture, anti-traditionalism, and the principle of the primacy of quantity over quality.”

Zyuganov blames Yeltsin and his circle of “radical westernizers” for destroying the Soviet Union and trying to graft onto the new Russian state all the sort of alien features embodied by the stock exchanges, strip joints, and burger palaces that so infuriate all nationalists. But soon, he writes,

it became evident that a significant number of Russians did not accept this path of development that the radical democrats were trying to take. The dissatisfied people grew in number into a real mass opposed to the general and deepening chaos that was the unavoidable result of the political and economic course of the Russian leadership. This dissatisfaction reached a critical mass.

One cannot entirely fault Zyuganov’s political analysis. Even democrats like the human rights champion Sergei Kovalev have admitted that the majority of average Russians have far from accepted the basic principles of democracy and a free market. Considering the cynicism of Yeltsin’s democratic leanings and the criminality of the economy, it is not hard to understand why this is so.

Out of popular confusion and disenchantment, Zyuganov has fashioned a resonant world view. There is probably no phrase that infuriates Zyuganov and the nationalists more than “the New World Order.” The American-led alliance in the Gulf War in 1991 marked for Zyuganov a humiliation and a warning: the United States now clearly treated its once-great rival and superpower, the Soviet Union, as a “junior partner.” Bush’s notion of a New World Order meant unchallenged American power. The New World Order, he writes, is the fulfillment of a

messianic, eschatological, religious project, thought out and based on plans long known in the history of planetary utopias, like the Roman imperialism in the time of Tiberias and Diocletian… and the movement of Protestant fundamentalists in Europe or the Trotskyist notion of World Revolution.

The New World Order, he continues, is part of a “post-Christian” religion.

Its ideology (we recall The End of History by F. Fukiyama) comes in the form of a messianic dream, held by the West for many centuries, of a liberal-democratic “heaven on earth.” This same ideology of mondialism [sic] is convinced of an imminent arrival on earth of Messiah, which would confirm on Earth the laws of the truth religion and provide the basis for a “golden age” of humanity.

The planet would be ruled over by “a united world government” supported by representatives of the Trilateral Commission, the American Council on Foreign Relations, and, of course, “other intellectual centers of mondialism.” Harvard University is the suspect “brain trust of world liberalism” where Western intellectuals and policy makers worked out the New World Order prior to the final collapse of the Soviet Union and the “bi-polar geopolitical construct.” There is also much conspiratorial discussion about the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, Jacques Attali, and the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development, who all go out of their way to undercut the power of Russia. The IMF’s recent ten-billion-dollar loan to Russia is simply a stratagem to make Russia beholden to the West.

Zyuganov, of course, does not mention these fantastical notions of the West when he visits Davos, Washington, or New York. He never mentioned them when he was invited to a group meeting with President Clinton at the American embassy in Moscow last year. Nor is he foolish enough to give voice to a kind of ritual anti-Semitism that runs through so much of the nationalist movement. Like his varied compatriots on the pages of Prokhanov’s newspaper, however, Zyuganov writes in his book I Believe in Russia that beginning with the nineteenth century there has been much to fear from Jewish influence:

The ideology, culture and world outlook of the Western world became more and more influenced by the Jews scattered around the world. Jewish influence grew not by the day, but by the hour. The Jewish Diaspora traditionally controlled the financial life of the [European] continent and became more and more the owner of the controlling interest in all the stocks of Western civilization and its socioeconomic system.

Zyuganov, and, more often, his more virulent supporters, like Prokhanov, are quick to point out the occasional Jewish name or face in the “party of betrayers.” Trotsky, of course, is a leading member, and a couple of Yeltsin’s more liberal advisers, such as Emil Pain, are guilty of various and sundry crimes.

This anti-Semitic aspect of the campaign is not a marginal aspect of Zyuganov’s strategy. Like Stalin in wartime, Zyuganov has decided that the Russian Orthodox Church is an essential aspect of Russianness and patriotism. He supports not only freedom for the Church, but also a kind of spiritual singularity. The God of the Jews and of Western Christianity is alien to the Russian people, and for them he promises nothing. It is on the question of his own spiritual life that Zyuganov reveals just one of the oddities of trying to reconcile his fealty to Bolshevism with his Slavophilic nationalism. He told one interviewer that, for him, Christ was “the first Communist,” since both Jesus and the Party “come from the same principle of social justice on earth.” He doesn’t go to church, exactly, but he is spiritual, “rather like Marshal Zhukov,” who did not go to church either but kept an icon hanging in his house.

5.

It is very much the fashion these days to say that the Russian election does not much matter. Yeltsin has proved his awfulness. He, too, has flirted with nationalism. His war in Chechnya has led to thirty thousand dead. He has failed to win a political consensus for democratic and market reforms. How much worse could Zyuganov really be?

Well, Zyuganov promises broadly in Davos that he would not dare renationalize property, but in Russia he makes it clear that is not the case. Zyuganov promises that the resurrection of the old Soviet Union would only come through voluntary association; then along comes General Valentin Varennikov (a conspirator in the 1991 coup attempt and now, naturally, a member of the State Duma) promising a more draconian plan of action than anyone has dared reveal. “We have a Program Maximum, which is not published,” he said. “First, let’s take power, and later we’ll talk about the plan.”

Zyuganov makes it clear that we can likely expect Russia, under his leadership, to assert itself strongly and, possibly, erratically, largely out of a sense of vengeance. His insistence that the West has brought Russia low and is now out to sap it of all strength and resources is a strain that is present in all his essays, speeches, and interviews. This xenophobic strain will bring harm, most of all, to Russians. “It is extremely important,” he writes, “that Russia avoids deepening its integration in the ‘world economic system’ and the ‘international labor force.’ That could bring on a dangerous dependence of the country on external factors. There is a need for maximal autonomy.”

Zyuganov writes that Russia must go through a period of healing and “internal evolution” after the trauma of 1991, but he also has in mind a re-exertion of influence over all the countries that were once in the Soviet sphere, including Eastern Europe. He writes with great admiration about Tsar Alexander III, who reigned while Russia’s “southern border went one thousand kilometers toward Afghanistan.” These cannot be pleasant notes to hear if one is living in, say, Estonia, Ukraine, or possibly even Eastern Europe.

The idea that Russia, as a great power, should have the ability to develop its own sense of identity and presence in the world free of Western pressure is now widespread and quite natural. There are no politicians of consequence in Moscow who say otherwise. There is no inherent harm in this, and for Americans to treat Russia with anything less than respect is not only arrogant, it is politically counter-productive.

It is also natural that, in Russia’s search for itself and bearing in the world, it should sort through what Zyuganov calls the “thousand-year experience of Russian statehood.” But we also ought to be aware—and hope that Russian voters are aware—that by looking closely at the ideology that Zyuganov has shaped one can see the potential for untold peril. His romantic, Slavophile vision of Russians as a people apart—a people with a superior sense of spirituality, with an innate belief in the collective over the individual, with a mission in the world to battle the West—is an ideology that is bound to have consequences. Unlike Yeltsin, for instance, Zyuganov would be more inclined to use political and even military pressure to win concessions in the former Soviet states; nor is Zyuganov particularly interested in cooperating with the West on issues like the Middle East or nuclear non-proliferation.

Zyuganov comes from a stream of the Communist Party and of the Slavophilic world that bears a hatred for the West that is hard for us to imagine. He may not reveal it in Davos, but in his words to the Russian people it is unconcealed. He is prepared to take legal actions against his predecessors for ending the Soviet Union and he is prepared to reinstitute a swagger that the world has not seen from Moscow in a decade.

“I always want to make it clear to the [West],” Zyuganov writes, “that you cannot destabilize a great country. You cannot force upon another your values and, force on us your vulgar films, this consumer psychology, these endless advertisements, which cause division in every family. You are instilling in us an anti-Americanism. Even during the cold war, there was not the anti-Americanism there is now.”

So far, Zyuganov leads Yeltsin in the polls despite the President’s mainly successful strategy to keep his challenger out of the media. Yeltsin’s numbers are rising, but he is still running second to Zyuganov. There are those in Russia and in the West who blithely inform us that restoration of any kind is simply impossible in Russia, that the Communists, no matter how determined, will never be able to move backward. The state is too weak, too poor, and too divided. All sides crave stability. This is partly true: empire is a project that will probably prove too expensive and exhausting even for the most determined Russian leader. But considering how fragile are Russia’s new political and economic institutions, considering Russia’s historical penchant for xenophobia and tragedy, one wonders at the origin of such complacency. Does anyone with a sense of history believe that the cause of human rights, a free press, and the evolution of democratic institutions could progress under a Communist regime? Zyuganov is capable of setting back Russia for many years, and some of the less measured figures at his side could do even more damage.

After Zhirinovsky’s party scored so well in the parliamentary elections of 1993, reporters asked one liberal democrat, Anatoly Shabad, what the West could do in the face of such depressing results. Shabad answered, “Wait and tremble.” It would be useful to remember that Russia operates on a presidential, not a parliamentary system. In anticipation of the Russian elections this summer, Shabad’s advice holds, many times over.

—April 25, 1996

I would like to acknowledge Masha Lipman of Itogi Magazine and Adrian Karatnycky of Freedom House for helping me obtain these books and for sharing their thoughts on Zyuganov’s evolution.

This Issue

May 23, 1996