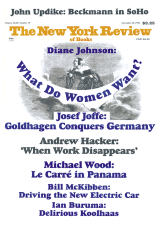

Descend with me to lower Broadway and the Guggenheim Museum there (suggestive, in its converted old warehouse, of a discount outlet for the goods on display in the chic spiralling main emporium on upper Fifth Avenue) and discover, upon arising from the subway and perambulating half-gentrified streets thronged with jubilantly hairy youths and tall thin girls clad entirely in this season’s remorseless black, and then upon threading through the bustling museum shop, with its plastic spread of modernist kitsch, past the vast flashing bank of computer-manipulated, laserdisc-fed television monitors designed by Nam June Paik and entitled Megatron—discover, I say (its doors as discreetly marked as its financial sponsorship by Lufthansa and Deutsche Bank), an exhibit of twenty-one late paintings, including seven of his famous triptychs, by Max Beckmann (1884-1950).

What have we here, so incongruously nestled under a second-floor show of electronic manipulations and virtually empty rooms called Mediascape? We have painting, pure and simple—painting that in its clarion colors, packed human groupings, and unmistakable metaphysical intent recalls the grand European tradition. We are challenged, in this age of acute aesthetic impatience, wherein visual stimulations have the duration and subtlety of electric shock treatments, by works so nakedly, simply representations in pigment and yet so stubbornly withholding of easy pleasures and a clear message. Some sort of colorful struggle is going on, but in terms almost entirely selfish, with no appeal to a public, by a sensibility to whom the Self is a self-evidently potent entity.

Beckmann, like Thomas Mann a scion of the German merchant class, was born into an intellectual world where Hegelian categories still shaped vision. Also like Mann, he was considered, by his avant-garde peers, to be conservative. He posed for himself in a tuxedo, for instance, and he disliked paintings that looked abstract or flat. In the pre-World War I hurly-burly of artistic theorizing, he disavowed connection with the brief-lived German Expressionist groups die Brücke and der blaue Reiter. He claimed to have no program, stating in 1914 that “all theory and all matters of principle in painting are hateful to me.” Nevertheless, he could issue pithy statements with lofty overtones. In 1938, a year after leaving Germany forever, he stated before an English audience:

What I want to show in my work is the idea that hides itself behind so-called reality. I am seeking the bridge that leads from the visible to the invisible…. It may sound paradoxical, but it is, in fact, reality which forms the mystery of our existence…. One of my problems is to find the self, which has only one form and is immortal…. Art is creative for the sake of realization, not for amusement; for transfiguration, not for the sense of play. It is the quest of our self that drives us along the eternal and never-ending journey we must all make.

Nine years later, addressing his first art class in the United States, he again insisted on the role of the self in painting:

If you want to reproduce an object, two elements are required: first, the identification with the object must be perfect; and second, it should contain, in addition, something quite different. This second element is difficult to explain. Almost as difficult as to discover one’s self. In fact, it is just this element of your own self that we are all in search of.

He painted more self-portraits than any significant artist since Rembrandt. (A forthcoming collection of his writings, including artistic statements, speeches, diary entries, letters, and a pair of turgid plays, bears the fitting title Self-Portrait in Words.) The SoHo show, Max Beckmann in Exile, contains a portrait of himself in white tie and tails (1937), another in an orange-and-black-striped clown’s or prisoner’s outfit, with a horn (1938), a third with his second wife, Quappi (1941), and still another as an acrobat squatting on his trapeze (1940). Additionally, a visage very like his own figures in costume paintings like The King (1933, 1937) and Actors (1941- 1942). All his symbol- fraught canvases, especially the triptychs, give an impression of transmuted autobiographical discourse. Generally, he makes of his own face a challenging, militant complex of dramatically contrasting planes; he edits out what we see in the photographs of him—a jowly, liquid-eyed softness, a watery burgherish humanity. In his art he appears as a fierce quester, a knight of the self-search. In the large 1937 image, done the year when Hitler’s aesthetic vandalism is about to drive him out of Germany, unease shows in the off-center pose, which leaks off the left edge of the canvas, and in the tipping, unreadable perspective of the stair on which he stands, and the striking hands, so heavy and large as to be useless; but the face is indomitable.

Beckmann took on heroic stature with the work he did in exile in Amsterdam from 1937 to 1947, followed by three years, before his death, in the United States. Long well-known and admired in Germany, he was named a degenerate artist by the Nazis, and over five hundred of his works were removed from state museums. In Amsterdam, where his wife’s sister lived, the Beckmanns rented a small apartment in a narrow gabled house; the attic was a tobacco storeroom, with a skylight. Here, amid wartime privations that may have helped to concentrate his attention, he painted as much as ten hours a day, and carried forward the series of triptychs that had become his special mode of ambition and of connection with the masterworks of the past.

Advertisement

However, the best-known of these, Departure (1932-1933; see next page), which hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, was painted when his own departure and the horrors of the Nazi era lay in the realm of foreboding. For all the obscurities of its symbolism, the triptych offers a clear and memorable contrast between the side panels, which seem to show scenes of torture in a palace basement, and the central one, with its royal family embarking on a pellucid sea in an atmosphere of sunny calm. The king’s crown rests squarely on the blue horizon line, and we do not need an interpreter to tell us that Departure is about freedom and domestic peace and their opposites. The centerpiece has an unforced mythic largeness; its saturation in blues reminds us of a sentence from Beckmann’s 1938 description of color as “the strange and magnificent expression of the inscrutable spectrum of Eternity.” His pallid, cartoonish earlier style, with its doll-like figures, has been overthrown by a brilliant brusqueness of attack.

To use the rather Nietzschean term of some contemporary critics, Beckmann is a “strong” painter: his stained-glass colors and emphatic black outlines announce his presence on a museum wall from afar. Powerfully attracted, we draw closer and are put off, puzzled by the ambiguities and crudities of the representation. His painting is just that, and not drawing; Beckmann could not, or would not, draw: his figures are lumpy and misshapen, with comically ponderous feet and hands that are all fingers. More than one of his women seems to have her head on backwards, and he is brutally fond of impossibly parted legs. Nor is his painting, in its exile phase, illustration, as were his Bibli-cal panoramas of 1917 or his immense study of Titanic survivors (1912). Even in a simple canvas like Falling Man (1950; see page 15), it is hard to know what is happening, amid this billowing smoke and these little winged nudes standing in cockleshells; the very sensation of falling is negated by the foot that just reaches over the top edge of the canvas, so that the man seems to be more dangling than falling.

In the triptychs, the figures are crowded like frat brothers in a telephone booth or cardboard cutouts in a display window, with small regard paid to the laws of perspective. Beckmann almost deified space, claiming:

The essential meaning of space or volume is identical with individuality, or that which humanity calls God. For in the beginning there was space, that frightening and unthinkable invention of the Force of the Universe.

Yet he gives us, with few exceptions, a shallow space crammed to the point of claustrophobia with bleakly staring, unrelated figures. Blindman’s Bluff (1944-1945) is an especially disquieting example of this tendency; possibly intended to compare barbarism, indicated by a drummer, and civilization, embodied in a harpist, side by side, the central painting and its side pieces are so overloaded as to suggest only a jammed apartment party in which no one can hear anyone else.

Reinhard Spieler, in his catalog essay on the triptychs (translated from the German by Isabelle Moffat), makes as much sense of them as they are likely to yield. Their myriad population, in Spieler’s careful accounting, holds five recurring figures—the king, the warrior, the bellboy, the young man, and the woman. As to their settings, “Four main areas in which Beckmann staged his dramas can be identified: the theater or stage (including the circus); the temple (or place of ritual); the bar, pub, or dance club; and the artist’s studio.” In the first six triptychs, Spieler detects allusions to contemporary events in Nazi Germany; for him, the nine completed triptychs form a kind of running exploration, like Auden’s poems or Tolstoy’s later fiction, of how men should live.

The last completed triptych, The Argonauts (1949-1950), according to Spieler “is Beckmann’s painted hymn to the mission of the arts to assist humanity in its search for knowledge.” This may be true; The Argonauts does seem the simplest triptych, the one most inertly submissive to a reductive reading. But why is the painter in the left-hand panel taking as his model a steatopygous bare-breasted Amazon clutching a phallic sword, and why is the sky of the central panel so crowded with barbaric omens? Discordant, random elements frustrate every attempt at strict allegorical interpretation. The making of a painting clearly meant more to Beckmann than the spelling out of a helpful humanitarian message. He does not coolly issue a generalized meaning but strives to body forth what has meaning for him, however obscure. In a “creative credo” issued in 1918, he said:

Advertisement

I believe that essentially I love painting so much because it forces me to be objective. There is nothing I hate more than sentimentality. The stronger my determination grows to grasp the unutterable things of this world…the tighter I keep my mouth shut and the harder I try to capture the terrible, thrilling monster of life’s vitality and to confine it, to beat it down and to strangle it with crystal-clear, razor-sharp lines and planes.

When told by his dealer, Curt Valentin, that some clients wanted an explanation of Departure, Beckmann wrote him,

Take the picture away or send it back to me, dear Valentin. If people cannot understand it of their own accord, of their own inner “creative sympathy,” there is no sense in showing it…. The picture speaks to me of truths impossible for me to put in words and of which I did not ever know before. I can only speak to people who consciously or unconsciously, already carry within them a similar metaphysical code.

Approached with my own code, the triptychs present a patchwork of opulent color in which the pallor of flesh flickers tantalizingly. Beckmann skillfully strikes the bright note of bareness in the king’s back in Departure, the bare limbs and torso in Acrobats (1939), the embonpoint in Actors (1941-1942), the enticing legs and shoulders in Carnival (1942-1943) and Blind Man’s Bluff (1944-1945). Not every modern painter makes bare skin electric; Degas and Modigliani can do it, but not Cézanne and Matisse. The Old Masters, with their goddesses and Oriental queens, do it all the time. It is Beckmann’s love of flesh that keeps his painting from being the “two-dimensional spatial experience” that amounts, he said in 1928, to mere “applied art and ornament.” In the painting Afternoon (1946), the woman’s bared thighs flash seductively, piteously, as her Moorish assailant seizes her wrist. Not in the SoHo show are such reposing nude couples as Odysseus and Calypso (1943), Brother and Sister (first titled Siegmund and Sieglinde, 1933), and City of Brass (1944), which have a near-pornographic effect, less through their details than their overall blaze of flesh. Beckmann twisted in the grip of sex; in 1946, he wrote in his diary,

Cold rage rules my soul. Should one never become free from this endless disgusting vegetative corporeality…. Boundless contempt for the lewd charms with which we are coaxed again and again to take life’s bit.

Even his boyhood was invaded by unchastity: the triptych Beginning (1946-1949) has in the foreground of its central panel a trollop in a blouse and stockings, blowing bubbles (like his youthful self in the painting of circa 1910), while a boy rides a white rocking horse and brandishes a sword. The right-hand panel shows, in Beckmann’s blocky, Légeresque final style, a classroom, and nearest to the viewer one male pupil is surreptitiously passing another an image of a naked woman.

In the left-hand panel, the boy hero is looking into a Christmas window while wearing a crown. I take this to signify that in our individual self-hood we are all kings (or queens); life is therefore a palace, a royal pageant, a circus, a performance in which people do stunts, play parts, wear masks. Through all this crowded and colorful show a sordid secret flickers: the fish in Beckmann is the symbol less of Christianity than of our slippery, odorous, expressionless genitals. Journey on the Fish (1934) is also titled Man and Woman, and shows them bound to two huge fish. In another early canvas in this exhibit, The Little Fish (1933), a young man shows his fish to two women; one lifts a finger in admonition but the other, who meekly gazes, is painted in her throat and cheeks with a beautiful rosy tenderness. Whatever else they are about, triptychs like Carnival and Blind Man’s Bluff are about gender relations—sometimes supportive, sometimes fraught. In the left panel of Departure a man and a woman are bound together, foot to face; in Air Balloon with Windmill (1947), a couple is caged together; in The Rescue (1948), the Tahitian couple are on the verge of copulation; even in the depths of Bird’s Hell (1938), his most direct and furious presumed allusion to Nazism, a woman with four breasts dominates, arising blue from her Boschian egg.

The triptych evolved for use in churches, and Beckmann was in his fashion a religious man, who spoke of God in his artistic credos and read not only German philosophy but gnostic and Buddhist texts, the Vedanta and the Kabbala. When he writes of strangling and beating down the “thrilling monster of life’s vitality,” and of becoming free of “this endless disgusting vegetative corporeality,” his language prepares us for the stabbing, garish quality of his painting and the irreducible ambiguity of his meanings. A triptych not on display in the Guggenheim Museum SoHo is Temptation (1936-1937); Beckmann might be described as one of those dialectical spirits for whom the world looms as a simultaneously alluring and repellent temptation.

This Issue

November 28, 1996