Most discussion of the black urban underclass is statistical or otherwise theoretical and removed, treating it as if it were life on an inaccessible planet. What makes Rosa Lee, Leon Dash’s report on a particular Washington ghetto family, so convincing and so valuable is his intimacy with his subjects, an intimacy that very few writers about the underclass have ever achieved. Dash had to do his work in neighborhoods that are dangerous enough to daunt most experts on poverty, and he had to overcome the deep suspicion toward outsiders that members of the underclass tend to have. That he won the trust of the people in his book is a testament to his dedication and commitment—Dash has been working on this project since the beginning of 19881—and, probably, to his refusal to condescend to them, to be falsely ingratiating or judgmental.

Dash presents himself, both to the family he is writing about and to his readers, as a sympathetic but absolutely uncompromising truth-teller, no matter how unpleasant the truths are. “My precise intention,” he writes, “is to make the reader as uncomfortable and alarmed as I am.” About the possibility that the facts of his subjects’ lives might not be “representative,” or will contradict liberal opinion, or will be misused by tendentious readers, Dash refuses to worry. He has dedicated Rosa Lee “to unfettered inquiry.”

The central character of Dash’s story, its heroine so to speak, Rosa Lee Cunningham, is a woman in her fifties who occupies the next-to-bottom rung of American society: at the very bottom would be people living on the streets or in institutions. Rosa Lee and her family live independently in Southeast Washington, but barely: they are on welfare and food stamps, and they are in and out of hospitals and jails. Beyond receiving government benefits, Rosa Lee supports herself as a drug dealer, a petty thief, and a prostitute. She is the unwed mother of eight children with five different fathers. She is illiterate. Although she is poor, the word “poverty” is pitifully inadequate to describe her problems. Extreme social disorganization and isolation from the American mainstream would be closer to the mark.

Rosa Lee’s parents were sharecroppers in North Carolina who migrated to rural Maryland in l932—and then to Washington in 1935, the year she was born. Her father, Earl Wright, was a manual laborer, became an alcoholic, and died young. Her mother, Rosetta, worked as a domestic, which was the standard employment well into the 1960s for uneducated black women living in cities. At fourteen Rosa Lee had her first child out of wedlock and dropped out of school. She had another child at fifteen and another at sixteen, the latter followed by a four-month marriage to the baby’s father. She had five more children, all out of wedlock. During most of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, Rosa Lee, her mother, and the nineteen children they had between them, at times living together and quarreling in a single small apartment, were one big, unhappy family.

In her early teens Rosa Lee began shoplifting from department stores, which became her lifelong vocation. In her early twenties, while working as a waitress in nightclubs, she began to deal heroin. She took customers home after work, often to the very bed she shared with her young daughter Patty. In her late twenties she was caught stealing a fur coat and was sent to jail. In her late thirties, after being left by a woman with whom she had had a lesbian relationship, she became a drug addict. Patty, by then a teen-ager, gave Rosa Lee her first injection of heroin.

Such a summary sounds both clinical and sordid. But through a combination of meticulous observation and empathy, Dash has managed to create in Rosa Lee a vivid, complex, and entirely convincing character, as rich as a character in a novel. What is particularly striking about her is that she isn’t passive or defeated. She has many strengths, like resourcefulness, love for her children, and aspirations toward a decent life, as well as weaknesses, drug addiction in particular. Dash sees her life as a struggle between them.

Rosa Lee is never presented as the Other or as a nobly suffering victim. Dash doesn’t try to gloss over her failings—in fact he is relentless in bringing them to light. At one point Ducky, the youngest of Rosa Lee’s sons, tells Dash that he has decided to devote his life to serving Christ, a common pose in the ghetto to impress a middle-class outsider. Dash won’t have any of it: “Finally, I interrupted. ‘Your mother has told me that you cook powdered cocaine into crack for New York City dealers operating out of your sister Patty’s apartment in this building and that you have been addicted to crack for some time now.”‘

Advertisement

Dash’s candor and his painstaking accumulation of details overcome any dehumanizing effect that the story he gives us might have. He begins his account by telling us that “Rosa Lee’s daily life consists of one crisis after another,” and then shows us the crises unfolding. Because he himself is a central character in the story his own reactions serve as a bridge between the two worlds, ours and the ghetto, and it is through Dash and through her relation with him that Rosa Lee comes to vivid life.

During the years that Dash spent with Rosa Lee, she was struggling with drug addiction and disease (she was HIV-positive, and was enrolled in a methadone program), and particularly with the all-consuming problems of her dependent adult children. Of her eight children, two escaped the ghetto and hold conventional jobs. One, Alvin, owns his own home. But the other six children are nonfunctional, and completely dependent on their mother. They spend their lives moving between Rosa Lee’s apartment, the streets, and jail. Richard sells the food out of the family’s refrigerator to buy crack. Ronnie contemplates openly committing a crime so he can be sent to jail, because he will be warm and well-fed there. Bobby, an HIV-positive homosexual prostitute, refuses to take medication or use condoms because (he tells Dash from jail, where he has been sent for dealing drugs) “I don’t want to live.” Patty, the child Rosa Lee is closest to, is a prostitute and desperately addicted to heroin and crack. In 1992, she agreed to let a group of thieves into her boyfriend’s apartment for twenty-two dollars; as soon as she got the money she left to buy crack, leaving the thieves to enter the apartment, where they killed him.

Dash describes what happened when Rosa Lee got a check for $1,298 from the federal Supplemental Security Income disability program, for which she became eligible when she tested positive for the AIDS virus. Rosa Lee herself at this time is off drugs except for methadone:

The check arrives at 1:30 PM on a Tuesday and Rosa Lee cashes it at a suburban Maryland liquor store. Wednesday morning, Rosa Lee tells me what happened when she went home.

Richard, Patty, and Ducky were sitting in the living room looking at her as she walked through the apartment door…. Rosa Lee agreed to give each of them fifty dollars and asked that they not bother her for any more money…. All three of them ran out of the apartment to buy crack.

Richard returned to beg for more money at 5 PM. Patty came into Rosa Lee’s bedroom a few minutes after Richard. And then Ducky came in. Rosa Lee gave them each twenty dollars. They left. The begging, Rosa Lee caving in, and her children returning to wake her up, continued until 5 AM.

Dash makes it clear that Rosa Lee is complicit in her children’s addiction, and not only because she constantly gives in to them. The blame, he sees, goes further back. Rosa Lee was indifferent to whether they went to school as children, and today only three of her eight children can read. It was Rosa Lee who gave her own daughter, Patty, as well as her son Eric’s girlfriend, their first tastes of heroin. She even sold Patty’s sexual services to men when she was only eleven, splitting the fee with her: forty dollars for Rosa Lee, ten for Patty.

The fathers of the children have been continually absent. When Ronnie encounters his father for the first time in eleven years, the man asks him for fifty dollars for heroin. Dash presents such moments deadpan, without calling for a response, whether of outrage or pity; indeed, sometimes the lives he describes seem as much comic as tragic. For the first time in thirty-five years Rosa Lee comes upon one of the fathers of her children: he happens to be the US marshal assigned to a bus taking her to prison. She doesn’t recognize him.

The details of Rosa Lee’s life are harsh and truly shocking, and they make it impossible to place her in any Victorian category of the “deserving poor,” as she might have been in a more sentimental, less truthful book. But they also bring her world extraordinarily to life on the page in a way that it hardly ever is. Dash succeeds in making Rosa Lee a living character whom you can’t help being drawn to. He never, ever covers up for her. But he also sees what is in some ways admirable in her. Illiterate, she is amazingly enterprising. Tears streaming down her cheeks, Rosa Lee tells a judge who is thinking of sentencing her to jail for shoplifting that she is raising three grandchildren alone—which isn’t true. She gets a suspended sentence. In the methadone program she is enrolled in, she develops a profitable sideline: upon leaving the clinic, she retires to a coffeeshop nearby where she deals Darvon and Xanax to the other addicts. When she hears that her only husband, who had walked out after a very brief marriage back in 1953, has been bludgeoned to death by his addict girlfriend, Rosa Lee immediately arranges to get Social Security widow’s benefits for herself.

Advertisement

If the next generation, Rosa Lee’s addicted children, is more defeated than she is, and more helplessly in the control of drugs, the generation after that, to judge by the one detailed example Dash gives, is even worse off because of an additional disposition toward violence. Patty’s son Junior was born out of wedlock when his mother was fourteen. By the time he was two, his mother was hooked on heroin.

The year between the ages of four and five was a pivotal point in Junior’s life…. [H]e was hospitalized for several weeks for what he remembers today was a kidney problem. Patty says nothing was wrong with Junior’s kidneys. Junior’s penis was swollen and he could not pass his urine, she says, but, uncharacteristically, she declines to specify what happened to her son. Whatever occurred, from that point on Junior formed a protective shell around himself and attacked with a purposeful fury anyone he thought was trying to hurt him. He also developed a cruel streak.

Soon after that, Junior burned the family cat’s tail off on the stovetop. At eight he was bringing weapons with him to school and committing petty burglaries. Patty by then was stoned or else suffering from withdrawal pains virtually all the time. Once, when Junior stole money from her drug-dealer boyfriend, she sat by while the man beat him up. At ten, having been repeatedly arrested, Junior is brought to court with Patty for a parental-neglect hearing; Patty arrives at the hearing in a state of drug withdrawal, and tells the judge, “Go ahead and take him.” On the way home from the hearing, Patty and Rosa Lee, depressed, stop in a department store, steal some earrings and wallets, sell them on the streets, buy heroin, and shoot up in an alley.

Once Junior is in the reformatory, Patty makes no attempt to stay in touch with him, or even to find out where he is. The first time he is sent to jail, at the age of nineteen, Patty is so broke from her drug habit that she can’t post the $100 bail to have him released.

“There is something in [Rosa Lee’s] life story to confirm any political viewpoint—liberal, moderate, or conservative,” Dash writes, but the main impression one gets from reading Rosa Lee is that most of the standard explanations for the deep social breakdown that the underclass represents are inadequate. The bill abolishing the federal welfare program passed in a flurry of rhetoric that blamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children for the conditions in the ghettos: the familiar argument is that poor women have children out of wedlock in order to get welfare checks, and then sink into idleness because working would lose them their benefits. It is true that the flow of welfare is important to Rosa Lee and her children. The first of the month, without fail, the drug dealers and addicts gather outside the mailboxes in the ghetto in anticipation of the arrival of their government checks. Rosa Lee herself once turned down a marriage proposal from the father of three of her children because to have a husband would mean going off welfare (though Dash also points out that she might have married the man had he not been unemployed and an alcoholic).

But it is clear that “welfare payments and food stamps don’t begin to account for all the money that comes and goes in the apartment.” Over the decades, Rosa Lee is never off welfare, but she is always working too; because of drugs, both her income and her expenses are far above what the welfare system can possibly provide. She won’t be a domestic like her mother (“I didn’t trust white people…. Why would I want to work in their houses?”), and she can’t read, so her activities are limited to illegal work, or at least work off-the-books: dealing, prostitution, petty theft. It’s hard to imagine that with a cutoff of welfare benefits she would have entered the conventional labor market. Moreover, the out-of-wedlock teen-age childbearing that is the norm in her family appears to be not the result of economic calculations about welfare benefits but the continuation of a longstanding cultural pattern. Rosa Lee herself was born when her mother was fifteen.

One of the theories William Julius Wilson first put forth in his 1987 book The Truly Disadvantaged is that the lack of “marriageable men” in the ghetto contributes to the growth of the underclass; this is richly confirmed in Rosa Lee. But Dash’s account does not quite work as evidence for Wilson’s view both there and in his new book, When Work Disappears, that deindustrialization is the deeper cause of the ghetto’s problems. Wilson’s main example is Chicago, until recently his home town, which has lost hundreds of thousands of industrial jobs. But Washington, a city with an enormous poverty population of 120,000 people, or more than a fifth of its residents, was never industrial to begin with, and nobody in Rosa Lee’s family ever seems to have had the unskilled, decent-paying blue-collar jobs whose disappearance Wilson primarily blames for the deterioration of the black inner city. For most of Rosa Lee’s adult life, the main employer in Washington, the federal government, was booming, but virtually all government jobs are out of the reach of the illiterate. The problem seems at least as much educational as economic.

Racism as an explanation applies, at best, indirectly. For as far back and forward as one can see, the circumstances of everyone in Rosa Lee’s family have been foreordained because of race: no white people have been born into a community quite like today’s city ghettos or the row of sharecropper cabins in which Rosa Lee’s grandparents lived and where her mother was born. On the other hand, for decades Rosa Lee’s family seems to have had no direct contact with whites, except in courtrooms; it’s an unfamiliar if jarring note when Junior complains of being called “nigger” at the rural reformatory he’s been sent to.

Another theory, the neoconservatives’ contention that the black-power movement or, more generally, liberal rhetoric created the underclass by persuading poor blacks to abandon bourgeois norms,2 doesn’t fit with Rosa Lee’s utter ignorance of any political or cultural ideas of any kind. She is astonished when Dash tells her that the President in Washington is now a Southerner from Arkansas. During the 1968 riots in Washington, Rosa Lee led her children out into the streets—but only to steal, and stealing had already been her calling for many years.

The single most destructive force in the lives of Rosa Lee and her children is drugs. That drugs have such a stranglehold of course begs the question of what it is that makes this family so particularly vulnerable to them. Still it is drugs that have reduced Rosa Lee’s children to an almost-vegetative state, and it is drugs that generate their criminal activity.

Dash ends this disturbing book by describing a visit he made with Rosa Lee before she died to the North Carolina plantation where her family lived as sharecroppers before she was born. There he discovers that her mother and grandmother had both been raped repeatedly by their white overseers. These white men were able routinely to treat young female sharecroppers as sexual chattel, knowing that plantations were beyond the reach of the law. One of the incidents produced a baby, Rosa Lee’s older sister, whose father came one day and took her away with no explanation. No one in the family ever saw her again. Shortly afterward, they left North Carolina forever. Both black and white people in North Carolina told Dash that “Rosetta’s experience was not an uncommon one for black girls working on the farms…from the post-Civil War period up through the 1930s.”

Sporadic education at best; isolation from the rest of society; rampant trade in and abuse of illegal intoxicants (moonshine then, crack now); teenage pregnancy; no belief in any connection between playing by the rules and doing well in the world; frequent sexual abuse, violence, and disruption of family life: the links between sharecropper society at the lowest rungs and ghetto society today are unmistakable. Dash quotes Charles S. Johnson’s Growing Up in the Black Belt: Negro Youth in the Rural South (1941) on the subject of members of the black “lower-lower class”:

They are tenants, sharecroppers, and laborers on the farms, and the unskilled laborers and domestic servants in the towns. They add to the low economic level a thorough cultural poverty with confused values. Frequently they are condemned to permanent economic incompetence because of their family structure.

There are several good studies by close observers of black sharecropper life in the South—during the heyday of the sharecropper system, the first half of this century, there were no reliable poverty statistics, and experts had to go into the field. Johnson, John Dollard, Hortense Powdermaker, Arthur Raper, Gunnar Myrdal, and E. Franklin Frazier—all described sharecropper society as being unusually prone to violence and family dissolution. One of the earliest accounts of sharecropper life is in W.E.B. DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folk (1903). DuBois was describing life in Dougherty County, Georgia:

All over the face of the land is the one-room cabin…. It is nearly always old and bare, built of rough boards, and neither plastered nor ceiled…. The majority are dirty and dilapidated, smelling of eating and sleeping, poorly ventilated, and anything but homes. Above all, the cabins are crowded….

In such homes, then, these Negro peasants live…. The system of labor and the size of the houses both tend to the breaking up of family groups….

To note the similarities between sharecropper and ghetto society is not, however, to explain ghetto society entirely. In The Souls of Black Folk, everything that DuBois found alarming about sexual and family mores in the cabins was far less pervasive than it is today (DuBois was shocked that “[t]he number of separated persons is thirty-five to the thousand”), and he saw material want and family instability mostly as a holdover from slavery, bound to disappear over time. Instead these problems seem to have worsened within the rural South between the turn of the century and the end of the Depression, and to have worsened again, to an almost unimaginable extent, in the cities between 1950 and 1980. It is as if the closer the black very poor came to the richness of opportunity in America, the more dispirited and angry those who weren’t able to take advantage of it became.

What hope there is in Rosa Lee lies in the lives of Alvin and Eric, Rosa Lee’s two sons who escaped the ghetto. It is a mystery how people who grow up in the same environment can turn out so differently. Like their brothers and sister, Alvin and Eric did not have the support of an involved father or a home free of drugs, but Dash makes three points about them. They stayed in school longer than their siblings. In early adolescence, both boys caught the interest of a concerned, helpful adult (in Alvin’s case a schoolteacher and in Eric’s a social worker) who became a real influence in their lives. Both managed to get secure jobs in government, Alvin as a bus driver, Eric at the National Park Service.

Dash lets Rosa Lee’s life and those of her children tell their own story. He refuses to draw sweeping conclusions. The one pronouncement he is prepared to make is that the life of an illiterate is doomed. For “the majority of African Americans who moved up into the middle class,” he quotes himself telling Rosa Lee, “education was the route.”

It’s obvious from Dash’s account, however, that there are parents, like Rosa Lee and most of her children, who aren’t going to help to get their children educated. Where family, community, and religion can’t be relied upon, government seems to be the best option left. Every positive force in the lives of Alvin and Eric—school, counseling, employment—emanated from government, and government not as a mailer of checks, which can relieve only material want (unless they’re wasted on drugs), but as an actor. It is a pity that so many believe that the problem of the underclass was created by the very institution that has done, and can do, the most to solve it.

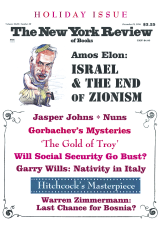

This Issue

December 19, 1996

-

1

An earlier version of this book was published as a series in The Washington Post, where Dash has been a reporter for thirty years, and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1994. I gave Rosa Lee a book-jacket endorsement.

↩ -

2

See, for example, Myron Magnet’s The Dream and the Nightmare: The Sixties’ Legacy to the Underclass (Morrow, 1993).

↩