“We enter into a covenant that we shall build a society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity—a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.”

—Nelson Mandela,

on his inauguration as President

of South Africa, May 10, 1994

At the beginning of this century, Mahatma Gandhi worked among the Indians of South Africa, organizing nonviolent protests from a settlement north of Durban. He built a school and a printing press, as well as his own solid brick house. Today, huts made of dried mud on rough timber frames crowd around the ruined buildings of the Gandhi settlement. Half-naked children play in the dust. There is no running water. Most of the huts have no electricity; most of their black African inhabitants have no work. And over the last decade the community now called Bhambayi has been torn apart by violence—murders, house-burnings, rapes—in a bitter war between one side, which is ANC-run, and the other, which supported the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). On one of the ruined buildings, you can still read the proud inscription “International Printing Press Founded by Mahatma Gandhi in 1903.” Lower down, there is a blood-red graffito. It says “Viva AK 47.”

The dusty patch on which the kids are playing football is, I am told, where the ANC side of the community holds its kangaroo courts. Only yesterday, a woman had been beaten up and then dumped with a few of her belongings by the roadside. Why was she expelled? Oh, because she was a witch. Wandering past the ruins we meet a short woman in a cotton-print dress, introduced to me as the “Minister for Safety and Security.” She simpers like a schoolgirl, shyly clutching her skirt and hiding her mouth with her hand. Can she tell us why that woman was expelled? Well, that woman was found outside a gentleman’s hut at four o’clock in the morning and couldn’t explain what she was doing there, so it must have been black magic.

The demarcation line between the two halves of the divided community is a small field. She says she would never cross it. The people there would kill her. But when we walk across, she follows, and even joins us in a friendly call on a woman called Beauty. So is the divide tribal, with the people over here being Zulus, like most Inkatha members? No, they are all Xhosa. They are the same people, speak the same language, live in the same kind of huts—and they have been killing each other for reasons that even the university social workers who are my guides cannot really explain. What would the minister do if the Inkatha side attacked again? Well, she would try to call the police. But you can never tell whose side the police are on. Often they are criminals too.

The social workers are trying to help these people to help themselves. In the community center, two women sew children’s clothes. Others make trinkets. Some of the local children are formed in a circle. One of them reads out a welcome to the visitor from England. Then they dance and sing. But I see no hope in their eyes. And how should there be, amid such desperate poverty and endemic violence?

From this, the black African shanty town that was once the Gandhi settlement, we drive back, past less impoverished but neatly separated coloured and Indian townships, to the rich business center of Durban. In the mirrored elegance of the Coffee Shoppe at the still absurdly colonial Royal Hotel, three smartly dressed young women sit gossiping and giggling at a corner table. One is white, one coloured, one Indian. At the next table are two even more lavishly dressed black African women, importantly taking calls on their mobile phones.

Welcome to the new South Africa.

Political perception, like treason, is a matter of date. If you want to judge anything written by a foreigner about a country, you need to know when the writer first went there. Was it in the bad old days? Or perhaps, for him or her, they were the good old days? Was it before or after the revolution, war, coup, occupation, liberation, or whatever the local caesura is? Of course the writer’s own previous background and current politics are important too. But so often that first encounter is formative.1 Emotionally and implicitly, if not intellectually and explicitly, it remains the standard by which all subsequent developments are judged.

So I can very well understand how people who knew the old South Africa may exclaim in exasperation: “But you don’t realize what it was like before.” And why those who worked for or merely lived through the “miracle” of South Africa’s negotiated revolution will hope against hope that the visionary promise of Nelson Mandela’s great inauguration speech may yet be realized. I feel that way about Central Europe and the promise of a great inauguration speech by another president, Václav Havel. But I can only describe what I saw and heard, on a first visit to South Africa, three years after Mandela became president.

Advertisement

I found a country of extremes, with some of the most beautiful and some of the most ugly human beings I have ever seen. I found men and women with heroic pasts, now in high places and still emanating dynamic optimism about the new rainbow nation. I found remarkably impressive ordinary black people—so many township Mandelas—rising above their circumstances. There was Japie, for example, a tall, handsome man living in Johannesburg. His father was an illiterate farm worker. Japie, like so many others, came to the gold-bearing reef of the Witwatersrand to labor in the mines, but he later worked his way up to a clerical post by sheer perseverance, intelligence, and self-discipline. Now he is sending his daughter “to varsity,” as he proudly puts it. (“Varsity,” for the benefit of American readers, is pre-war upper-class English slang for university.) A story of hope.

Yet of euphoria I tasted nothing, and most of what I found was grim. The inheritance is so terrible. Black poverty grinds against white riches, particularly on the reef, in what is now the province of Gauteng. Central Johannesburg is Manhattan in its skyscrapers, but with a more violent version of the Bronx on the streets below. The Cape is California with shanty towns. Economists say South Africa’s pattern of income distribution is one of the most unequal in the world. A few black Africans have become rich. The ANC’s chief negotiator of the new constitution, Cyril Ramaphosa, having been elbowed out of the competition to succeed Mandela, has gone into the investment and mining business with spectacular effect. They call him one of “the new Randlords.” Better-off blacks now live in previously all-white suburbs that look like Beverly Hills, but with security fences, gates, and armed guards more reminiscent of El Salvador.

For the most part, though, apartheid lives on as racial apartness. I talked to a bright black girl in the Johannesburg township of Alexandra. She had studied for three years at the University of Witwatersrand (known as “Wits”). Did she have white friends? “No, of course not.” They said hello or lent each other a pencil in the lecture hall. But she would never go to a party with whites, or anything like that. And only black students lived in the student hostels. What’s more, she did not want to have white friends. “Why should I?” she said.

Crime, as even the casual foreign newspaper reader knows, is an appalling problem. I shall never forget driving into the dark, deserted center of Johannesburg at night with Nadine Gordimer—the writer most identified with white liberal hopes for the new South Africa—crouched over the steering wheel, nervously on the lookout for carjackers. “Aren’t you frightened,” my cheerful young ANC guide teased me, as we drove back from visiting the grave of the communist leader Joe Slovo in the great, dusty cemetery of Soweto. The answer was no, but perhaps I should have been.

Violent crime soared in the last years of white rule. According to the statistics, from 1990 to 1994, murder increased by 14 percent, robbery by 57 percent, rape by 58 percent. The murder rate in 1994 was 98 per 100,000 people, compared to ten for the United States. Everyone has a horror story to tell. Some of the violence is still political. In KwaMashu, north of Durban, an investigator for the Truth Commission told me about an ongoing shooting war in his section of the township. This was not between ANC and IFP, but between two factions of the ANC: one home-grown, the other returned from exile. But the political violence has also transmuted effortlessly into criminal violence. The ANC or IFP “warlord” becomes mafia-style boss. The “third force” security killer now works in the deeply shady private security sector. 2 Dirty fortunes are made in protection rackets, smuggling, and dealing.

Everyone, in city, suburb, and township, tells you crime has got worse, not better, in the last three years. The police are widely seen as ineffective and deeply corrupt. The criminal justice system is at the point of breakdown. Dullah Omar, the brave and articulate Justice Minister, told me frankly that what they need is a new force to “police the police.” And he is planning a new prosecution service as well.

It’s not just the police. Large parts of public administration suffer from chronic inefficiency and corruption. I talked to several community counselors in black townships and they all told the same story. In many cases, pensions and social security benefits had not been paid for more than a year. The administrative mess is a result both of the historical disease and the attempted cure. History has left the country with a vast ramshackle structure of multiple bureaucracies which in 1994 employed a staggering two million of the country’s five million whites. This was “jobs for the boys” on a grand scale. A “sunset clause” negotiated as part of the transition means these people can keep their jobs until 1999—without any incentive to do the job well. Meanwhile, as part of the attempted cure, “affirmative action” brings black Africans into senior posts. But many of them are ill-equipped, for under the notorious system of “Bantu Education” blacks were deliberately given only the rudimentary schooling considered appropriate to Untermenschen. The emigration of skilled whites does not help either.

Advertisement

In a few respects, the government has delivered on its promises. Kader Asmal, the flamboyant Minister for Water, is rated one of the notable successes. While I was there, he brought to Cape Town a slightly bewildered old woman who he claimed was the millionth person to receive running water since the new government came to power. But the government is trailing badly on other commitments, such as the 1994 election promise to build 300,000 houses a year. The task of “reconstruction and development” is, of course, a gargantuan one. But on the main fronts—housing, education, health care, employment—what I heard from ordinary people, community activists, journalists, and even lower-level ANC activists was a litany of complaints. In practice the hospitals have gotten worse, though partly this is because everyone now has access to them. In practice, the schools are little improved. In practice the “Mandela sandwich”—the snack to be made available to every schoolchild during school hours—hardly exists.

And jobs? You’re joking. Sixty percent of the young men in the townships are unemployed, I was told. So what do they do all day? The large black lady in the church hall pauses for a moment and then says, with a smile, “They smoke.” Not cigarettes, you understand, but dagga, the local name for marijuana. They smoke, and then some go out and steal: a sheet of corrugated iron for the roof, some consumer goods from a white villa, or a car hijacked in broad daylight and brought home in triumph.

A glance at the underlying demography is still more discouraging. Two thirds of black South Africans are under thirty. The total population is projected to grow from today’s 42 million to 59 million by 2010. Then there are the illegal immigrants from poorer countries, streaming across the country’s northern borders and swelling the shanty towns of Gauteng. South Africa does not even have a Rio Grande. Moreover, there is an appallingly high incidence of AIDS, with 14 percent of pregnant women estimated to be HIV-positive.

Politically, one can also find depressing trends. When I ask the ebullient Kader Asmal to characterize South Africa’s current political system in a phrase, he says it is a “putative democracy.” Its critics describe it as a “one party-dominated state.” Parliamentary insiders say the tiny liberal Democratic Party is the only one to take seriously the job of parliamentary opposition. Debates in the echoing parliament chamber are little more than serial speechifying, not least because MPs can and do speak in any of the country’s eleven official languages. More substantial work is done in parliamentary committees.

Chief Buthelezi’s Inkatha Freedom Party remains—my experience in Bhambayi notwithstanding—largely confined to the Zulus. The National Party is the party not just of the whites but also of many of the Indians and the coloureds. A bright and enterprising young Indian told me their bitter saying: “Before, you were not white enough; now you are not black enough.” The ANC version of “jobs for the boys” means jobs for the black African boys. In 1994, the National Party was actually returned to power in the Western Cape Province by the votes of the so-called Cape coloureds. But this May, the National Party leadership decisively rejected an attempt by one of their brightest younger politicians, Roelf Meyer, to go beyond this Afrikaner rallying of the ethnic minorities to form a new, genuinely national, nonracial opposition party that could hope to win a significant number of black African votes as well.

So the ANC looks as if it is set to be in power for the foreseeable future. Its internal democracy leaves much to be desired. As the liberal Weekly Mail and Guardian commented in a third-anniversary editorial, the contest for the succession to Mandela as leader of the ANC was conducted behind closed doors, with observers “reduced to Kremlinology.” Conspiracy theorists even see the South African Communist Party as a kind of Broederbond inside the movement. Unsurprisingly, some of those who suffered for the cause, in exile or underground, now feel they deserve their just rewards: good salaries, nice cars, patronage, and perks. African nationalists turn the tables on Afrikaner nationalists, doing as they were done by for so many years. Whether in central government, local agencies, or universities, charges of incompetence or corruption are immediately deflected by the deadly countercharge of “racism.”

President Mandela shines above all this. He also practices what he preaches. He tries to have representatives of all the main ethnic strands in his office, and in other key posts, to symbolize and to lead the rainbow nation. Mandela is such an extraordinary, radiant, magical figure that his vision cannot be entirely lost so long as he is still there. But one gathers that the office of his heir apparent, Thabo Mbeki, is much more narrowly Africanist. The real test will come after Mandela retires in 1999, following elections in which the ANC seems likely once again to win a clear majority.

So pessimists can muster a formidable list of current problems and worrying trends to support the hypothesis that South Africa on the tenth anniversary of Mandela’s inauguration might look more like the rest of post-colonial, sub-Saharan Africa than like his luminous vision of the rainbow nation. Against this, however, there are some very important counter-arguments. For a start, South Africa’s leaders have the intellectual equivalent of what economic historians call “the advantages of backwardness”: that is, they can learn from everybody else’s mistakes. And postcolonial Africa is a superb textbook of mistakes.

They are also fortunate, as one ANC member of parliament commented to me, that the Soviet model of communism was finished before they set to work.3 When white liberals made their first tentative contacts with ANC leaders in the 1980s, they were horrified to hear them spouting pure Soviet-type economics. Ten years later, those same people, some of them still members of the Communist Party, are trying to implement economic policies that the IMF can only applaud. Their macroeconomic strategy for Growth, Employment, and Redistribution—GEAR—has hugely ambitious goals: growth of 6 percent by 2000, a deficit within the Maastricht target of 3 percent by the same year. But at least it is aiming in a sensible direction.

In pursuing these all-important economic goals they also have the advantages of forwardness: much the most developed economy in Africa, good roads, communications, and other infrastructure, an established legal and banking system, skilled professionals, and so on. Foreign investment has been disappointing, but it is slowly coming, and South Africa is the obvious base from which to work up into the rest of southern Africa.

No one could deny the devastation of South African society. But there is still an excitement that comes from the attempt—against all the odds—to build a new nation in which people of such diverse colors, creeds, and backgrounds work together. Some young Afrikaners may be emigrating, but others are throwing themselves into this attempt. The great irony of Afrikanerdom, after all, is that the Afrikaners, who are so closely identified with ideas of white racist supremacy, are in fact the only whites who really consider themselves to be a part of Africa. As for the apartness that remains after apartheid: that is not, in itself, a tragedy. Doubtless it would be better if, as Archbishop Tutu infectiously teaches, South Africans would all love one another. But if they just stop killing one another that is something to be going on with. Many countries in the world live with highly separated ethnic communities: the United States, to name but one.

You can also muster a substantial set of counterarguments against the suggestion that South Africa is headed politically toward a corrupt one-party-dominated state. For a start, the new republic has a carefully drafted, liberal constitution, passed last year to replace the interim constitution of 1993. This is being forcefully upheld by a very impressive Constitutional Court, headed by Arthur Chaskelson (once Mandela’s defense lawyer), and including such potent figures as Albie Sachs and Richard Goldstone. The ordinary courts, though desperately overburdened, still have a strong tradition of judicial independence. The country has a rich “rights culture,” developed in the long years of opposition to apartheid. There are independent human rights commissioners and an astonishing array of nongovernmental organizations. Many church leaders are also vigilant and eloquent advocates of respect for the innate dignity of every human being—and these churches still have congregations of which their European counterparts can only dream. I was struck by the way in which almost everyone I met habitually talked in terms of dignity and rights. Unfortunately, the independent press and television are not half so impressive, but there is still lively intellectual and journalistic criticism of the new powers-that-be. All in all, this strong legal frame, deeply rooted rights culture, and active civil society can go some way to compensate for the lack of a credible political opposition.

Moreover, there is always the opposition—or perhaps the oppositions—inside the ruling party. Of course, history knows many examples of people who fought heroically against one dictatorship, only themselves to erect another one. But the fight against apartheid inside South Africa also nourished a feisty attachment to democracy, and the ANC movement is itself a rainbow coalition. There are those who returned from exile and those who continued to live in the country under apartheid. There is the Communist Party trend, the powerful labor movement trend around the trades union congress COSATU, a nationalist-populist trend, and so on. There are also “dissidents” such as Winnie Mandela and the expelled former leader of the Transkei, Bantu Holomisa. The distinguished liberal journalist Allister Sparks argues that with time, and with a further differentiation of interests in the wider society, some of these might split, or form new alignments with other parts of the political spectrum. There could be a party of the middle class, a labor party, and, alas, a large populist party of the underclass and the radically disaffected. In any case, this diversity inside the ANC is a further obstacle to the construction of a monolithic, authoritarian regime.

What is true of the ANC may also be said of the country as a whole: its sheer complexity is both its curse and its blessing. In many other African countries there are just one or two major tribes, so that politics is plagued by the struggle between them. In the new South Africa, there are so many different tribes that it seems inconceivable that any one could now dominate all the others, as the white tribe of the Afrikaner did for nearly half a century. A hundred other intricacies and crosshatchings ensure, if not democracy, then at least diversity. The historical difference that allows one still to hope might frivolously be summed up in a pun. Where Rwanda has Tutsi and Hutu, South Africa has Tutu.

“Once we have got it right,” said the ebullient Archbishop on the day Mandela and de Klerk received the Nobel Peace Prize, “South Africa will be the paradigm for the rest of the world.” In this extraordinary piece of messianic optimism there is, I think, a grain of truth. If this incredible mishmash of colors, faiths, and traditions, of very rich and very poor, can emerge from such a terrible history and form a halfway functioning, civilized, liberal state, then there is hope for us all. Not just for the rest of southern Africa, the future of which depends so much on how South Africa develops, but for all other parts of the world where people are still attempting to build liberal, multiethnic polities.

Europe since 1989 has provided yet another synonym for the failure of that attempt: Yugoslavia. Judged by that standard of European civilization, the new South Africa is still very far from failure. We must expect that the reality of the South African “paradigm,” if it emerges, will be very different from the liberal democratic theory laid out in the republic’s admirable constitution. With a lot of luck, help from outside, and muddling through, it may nonetheless be a state of sufficient real-life pluralism, freedom, minimal welfare provision, and legality, so the basic rights and dignity of its people will not again be trampled underfoot. But when you see at first hand the violent misery of communities like Bhambayi, you come away feeling that even this would be a miracle.

—July 17, 1997

This is the second of two articles.

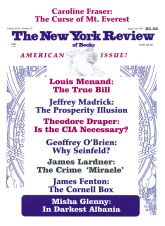

This Issue

August 14, 1997

-

1

An eloquent and moving account of one such formative encounter with South Africa, and the intellectual and political odyssey to which it led, is given by Per Wåstberg in his book In South Africa: Journey Towards Freedom, published in Swedish in 1995 (Stockholm: Wahlström and Witdstrand) and richly deserving an English translation.

↩ -

2

This is explored in a detailed and searching article on the whole phenomenon of the “third force” by Stephen Ellis, to be published in the Journal of Southern African Studies. Some bloodcurdling tales of recent criminal violence are told by Graham Boynton in his Last Days in Cloud Cuckooland: Dispatches from White Africa (to be published by Random House later this month).

↩ -

3

See my previous article, “True Confessions,” The New York Review, July 17, 1997.

↩