1.

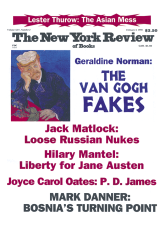

Vincent van Gogh was thirty-seven on July 27, 1890, when he shot himself in the chest on a quiet country footpath and dragged himself home to die in the attic room of a small auberge in Auvers-sur-Oise. It was only in the last two years of his life that he had found himself as an artist, first in the picturesque Provençal town of Arles, then in nearby St.-Rémy-de-Provence, and finally in the northern village of Auvers just outside Paris. It was in these years that he worked with passionate speed, using the thick impasto we now associate with his name. But his entire working life as an artist had only spanned nine years. In that time, according to the complete catalog of his work published in 1970, he executed 879 paintings, 1,245 drawings, and one etching. It has now been suggested that several dozen of the paintings, as well as the only known etching, are fakes executed by various of his contemporaries. That Van Gogh’s paintings are currently more expensive than those of any other artist gives the situation a special piquancy.

A fake is an imitation of an artist’s work which is passed off as genuine. Some of the paintings now thought to be masquerading under Van Gogh’s name may have been innocent imitations made by other artists who admired his style. Others, particularly the Paris period still lifes, may look like Van Goghs because Vincent himself discovered and adopted a variant of Impressionism that was used by many other painters in Paris at the time. Such paintings only became fakes when passed off as Van Goghs—the signature “Vincent” was added to many Paris still lifes painted by other artists. But there are also out-and-out fakes, painted with the purpose of deception.

How do we know? The time-honored method of recognizing fakes is to use one’s eyes. The sweep of an artist’s hand as he paints is highly individual. His brushstrokes are like handwriting and, just as forged documents can be recognized by a handwriting expert, forged paintings can be recognized by connoisseurs. In theory, at least.

In fact, Van Gogh was a highly experimental artist who was constantly trying out different styles. And his mental illness meant that his power to control the brush varied. Those who consider themselves experts on his work argue vigorously about what he painted and what he did not. They are broadly agreed, however, in branding as fakes a group of variants on genuine St.-Rémy landscapes, owned at one time by Amédée Schuffenecker and probably painted by his artist brother Emile. They are also agreed that Paul Gachet Jr., the son of the doctor who looked after Vincent in Auvers, passed off several imitations as genuine Van Goghs. And they agree as well that several of the Paris period still lifes are not by Van Gogh.

Once a painting is suspected on visual grounds, one looks for further evidence. Documentation of a painting’s early history is extremely important—though such odd things happen to paintings that it can rarely provide definitive proof. And there is scientific evidence, based, for example, on X-ray and chemical analysis. So far few of the disputed Van Goghs have been scientifically studied and it is unclear how much that could help. Since the disputed pictures were painted within a few years of Van Gogh’s death, other artists could have used the same canvas and paint suppliers.

That Vincent made many copies and versions of his own paintings further complicates the questions about his work. In the case of portraits, he would often make a copy for the sitter; when he was ill he would copy his own work for lack of other motifs; if he was dissatisfied with his rendering of a subject, he might try again. Many of the paintings over which disputes are currently raging are copies or variants of wholly accepted works. Good copies are very hard to detect—there are still arguments over many Old Master copies. A faker with a genuine painting in front of him is likely to be inspired by the spirit of the original and leave few traces of his own characteristic quirks of style.

Several of Van Gogh’s contemporaries are now suspected of knowingly passing off fakes as genuine. Attention has so far concentrated particularly on Emile Schuffenecker, who worked in the same stockbroking firm as Gauguin and left with him to become a painter, and Dr. Paul Gachet, the Auvers physician who watched over Vincent’s mental illness for the last two months of his life. Gachet’s son gave eight Van Goghs to the Louvre, probably including some fakes. But several other people may have had a hand in producing or selling fraudulent imitations: Emile Schuffenecker’s brother Amédée and their close friend Emile Bernard, the artist who worked in Brittany with Gauguin and helped launch Cloissonism; Ambroise Vollard, the famous Paris dealer in avant-garde art; Théodore Duret, the art critic friend of Manet; and several other, more obscure, figures.

Advertisement

Contrary to the general assumption, money is not the principal reason for creating fakes. The characteristic motivation that drives an artist to make them—and only artists are capable of it—is to prove to himself that he is as good as the artist he imitates. They are usually made by artists embittered by their own lack of recognition—as were Schuffenecker, Bernard, and Gachet. But the bohemian world of struggling artists is also inhabited by dealers and amateurs—such as Vollard and Duret—who know that art is not fundamentally about names and would not take the passing off of fakes too seriously. Vollard and Duret probably needed the money—but they also loved art.

There have been mounting allegations, denials, and counter-allegations over Van Gogh fakes in the world press, most especially the French press, during the last eighteen months. It all began when an undistinguished late landscape, Le Jardin à Auvers, was put up for auction in Paris in December 1996, unleashing a fierce debate over its authenticity—still unresolved. Then, in June 1997, the Journal des Arts published an investigation by Martin Bailey, an English journalist, suggesting that there might be as many as one hundred fakes in circulation. This was most frustrating for me personally since I had begun to do research on the Van Gogh fakes for a television program a year before—and my program was not due to be aired in Britain until October. As it turned out, however, the story is so complex and intriguing that there was plenty of information to be discussed.

The television program concentrated on presenting the evidence that the painting Sunflowers sold by Christie’s in 1987 to the Yasuda Fire and Marine Insurance Company of Japan for å£24.75 million—then a world record price for any painting—was a copy made around 1900 by Emile Schuffenecker. The original, the program concluded, is the painting Sunflowers now in the London National Gallery. Van Gogh made a copy of it himself which he intended to give to Gauguin, but his copy never left the family collection and hangs today in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. The composition—though not the execution—of all three paintings is identical, and in November 1997 the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, reacting perhaps to my television program, announced the intention of gathering all three paintings of Sunflowers under one roof—probably at the National Gallery in London—to make a thorough scientific study of the Yasuda version. The Amsterdam museum, which was given $37.5 million by Yasuda to build a new wing in the early 1990s, loyally supports the authenticity of the Yasuda painting. The curator of paintings, Louis van Tilborgh, has told me that they have no doubt about it and are sponsoring a scientific study merely in order to demonstrate to the public that the painting is genuine.

The Musée d’Orsay in Paris has also announced a new investigation. There is to be an exhibition in late 1998 of all the donations by Paul Gachet Jr. to French museums, after every painting has been scientifically tested and researched. The catalog of the show will give the official French response to the suggestion that Paul Gachet Jr. gave away fakes.

This is a welcome beginning but it is probably going to take decades to sort the problem out. At present the views of those who have made a special study of Van Gogh’s work are wildly conflicting. The voices that carry the most weight are those of the British art historian Ronald Pickvance, who organized the big Van Gogh shows at the Metropolitan Museum in the 1980s, and the Zurich-based experts Walter Feilchenfeldt and Roland Dorn. Feil-chenfeldt is an art dealer—the son of one of the great dealers of pre-war Berlin—while Dorn previously worked as a museum curator in Mannheim. Dorn and Feilchenfeldt are preparing their own catalogue raisonné.

The opinions of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam are also given much weight, though the museum’s curators of paintings and drawings, Louis van Tilborgh and Sjraar van Heugten, are comparatively junior in the pecking order of experts. Then there are Professor Mark Roskill of Amherst, Massachusetts, who published an important book, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and the Impressionist Circle,in 1970; Professor Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov of Toronto, who organized the recent Paris period show at the Musée d’Orsay; and Annet Tellegen, now eighty-five, who collected the information on which the 1970 catalogue raisonné—the authoritative source on Van Gogh—is based. She fought bitterly with the editorial committee appointed by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Arts, and Sciences, whose views on authenticity are reflected in it. The committee’s task was to revise and reissue Baart de la Faille’s Van Gogh catalog, first published in 1928; Tellegen wanted it to incorporate more new research than the committee did. The failings of the 1970 catalog are among the causes of the present muddle.

Advertisement

Dorn and Feilchenfeldt published an important article on fakes in 1993 identifying a group of copies which they attributed to Emile Schuffenecker. They discussed the proliferation of Paris still lifes and pointed to doubtful self-portraits. Bogomila Welsh, the art historian from Toronto, is working on a new study of Emile Schuffenecker. But the most provocative contribution to the investigation is being made by two outsiders, Benoît Landais and Antonio de Robertis. Both enthusiastically welcome opportunities to publicize their views.

Benoît Landais is the son of Hubert Landais, formerly director in chief of the Musées de France. Benoît’s previous careers included full-time revolutionary, round-the-world yachtsman, and writer. He now lives in a village outside Amsterdam and works on the Van Gogh Museum archives. Antonio de Robertis is a Milanese geometer—an Italian profession that lies somewhere between architect and quantity surveyor. In 1990 he won 100 million lire in a television quiz game, Lascia o Raddoppia(“Double or Quit”), by answering questions on Van Gogh and was able to spend his winnings on further research.

It was the Yasuda Sunflowers that set off Robertis’s investigation. He noticed that it was an odd size. Van Gogh normally worked on standard size-30 canvases (36 x 29 inches) and this picture has an inch or so extra height and width. At some point, extra strips of canvas were added around all four sides of a standard size-30 canvas, according to Christie’s. Robertis found several reasons for supposing it a fake: it is copied from the London National Gallery Sunflowers, whether by Van Gogh or not. The copy distorts the characteristics of several flowers and leaves, a departure from reality Van Gogh is unlikely to have made. The painting first appeared in a 1901 exhibition at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery as the property of Emile Schuffenecker and unlike the other sunflowers paintings it is not mentioned in Van Gogh’s letters. In 1994 Robertis’s theory was the subject of reports in both the Corriere della Sera and the Giornale d’Arte.

Most Van Gogh scholars challenge the pronouncements of Landais and Robertis who, they claim, have no grasp of the documentary history of Van Gogh’s oeuvre and untrained eyes. But they also disagree among themselves. Their arguments refer to a wide range of paintings, but three examples will give the flavor of the problem.

Annet Tellegen says that the Self-portrait with a Bandaged Ear in the Courtauld Galleries, London, is an “absolute fraud.” The portrait, complete with bandage, is, she says, copied from a similar picture now owned by the Niarchos family. The copyist has omitted the pipe in Vincent’s mouth but not unpursed his lips, while the studio background does not tally with the interior of the Yellow House where Vincent lived. Benoît Landais says the picture is perfectly genuine. Ronald Pickvance says he thinks it is genuine on Mondays and a fake on Tuesdays.

Walter Feilchenfeldt and Roland Dorn have accused a double-sided Self-portrait in the Metropolitan Museum in New York of being a fake. Their claim is based on the fact that Vincent is wearing a summer hat and winter suit, something they say he would not have done. They support their argument with the fact that the picture first turned up in Germany in 1928—at the time when a huge Van Gogh manufacturing operation was unmasked. No one else I have talked to agrees with them.

Professor Mark Roskill says that the Arlésienne in the Musée d’Orsay is a fake copied by Emile Schuffenecker from the similar painting now in the Metropolitan. He deduces this by pointing to elements of the original portrait which, he claims, the copyist has misunderstood and therefore misrendered. Emile Schuffenecker is said to be the likely copyist since he once owned the Metropolitan Arlésienne. Roland Dorn says the Orsay picture is genuine but has a damaged appearance since it was rolled around an umbrella to smuggle it out of Nazi Germany. Ronald Pickvance says the Orsay picture is a quick sketch from life by Van Gogh and the Metropolitan one is a more considered version that Vincent worked up later in the studio. Benoît Landais says that the Metropolitan picture is a fake based on the genuine painting in the Orsay.

2.

To understand how this muddle can have arisen one must look back at the story of Van Gogh’s own life and that of his family. The introduction to Vincent’s letters, written by his sister-in-law Johanna in 1914, gives a vivid account of how Vincent’s bourgeois Dutch family regarded him as an emotionally unstable dropout. He couldn’t hold down a job—even as a volunteer preacher in the Borinage mining district—and would come back to stay at his parents’ house between crises. He only began to concentrate on painting in 1881, at the age of twenty-eight, and it was his younger brother, Theo, who supported and encouraged him throughout the nine years of his artistic career. Theo worked for the Paris art dealers Boussod-Valodon and struck a deal with Vincent similar to those between many artists and dealers at the time. He took paintings in return for a small monthly retainer.

Vincent gave a few paintings away and sold some four or five in his lifetime, but Theo inherited almost his entire oeuvre. He became ill himself in the autumn of 1890 and died in January 1891, only six months after his brother. With Theo’s death all firsthand knowledge of when and how the paintings had been made was lost. There was thus no authority to resolve conflicting attributions.

Ownership of Vincent’s paintings was passed by unanimous family consent to Theo’s one-year-old son, Vincent Willem, thus giving Theo’s widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, charge of them—the family considered the paintings more or less worthless. And it was this young Dutchwoman, the daughter of an insurance broker, who put Vincent on the map. She organized international exhibitions and sales and built the Van Gogh myth by laboriously transcribing his letters—omitting anything she disapproved of—and getting them published.

A contemporary’s view of Johanna suggests she may not have had much understanding of Vincent’s work: “Mrs. van Gogh is a charming little woman,” wrote Roland Holst,

but it irritates me when someone gushes fanatically on a subject she knows nothing about, and although blinded by sentimentality still thinks she is adopting a strictly critical attitude. It is schoolgirlish twaddle, nothing more…. The work that Mrs. van Gogh would like best is the one that was the most bombastic and sentimental, the one that made her shed the most tears; she forgets that her sorrow is turning Vincent into a god.

It also irritated her son. “At home it was rapture, rapture all the time,” he wrote, “with no attempt to justify oneself. I was never taught how to understand art (paintings, music). I cared nothing about it. I respected it but regarded it as a sort of sorcery that was not for me.” Nevertheless he grew up surrounded by Vincent’s pictures. Born on January 31, 1890, he became an engineer and took very little interest in them until he had established a professional reputation of his own. In the 1950s, however, promoting Van Gogh’s paintings became his pet project. He organized exhibitions in Europe and America, traveling to the openings with his family. He also began to dream of having a museum of his own.

In 1962 a deal was struck. The city of Amsterdam provided the land for a museum, the Dutch government built it, and the Van Gogh family transferred their paintings to a new Vincent van Gogh Foundation—which lent them to the museum in perpetuity—in return for 18,470,000 guilders, about $9,235,000. The board of the foundation is made up of one family member representing each of Vincent Willem’s children and an official representing the state. To this day the foundation owns and manages the collection, including paintings by other artists that belonged to Vincent or Theo, all Vincent’s letters to Theo, and quantities of other archival material.

The problem of fakes seems to have first become a public issue around the time of the First World War. It was in 1917 that a young Dutch lawyer, Baart de la Faille, set out to compile a comprehensive list of Van Gogh’s authentic paintings. It was published in 1928 and within twelve months La Faille had to issue an errata sheet which added one picture to the list and subtracted three dozen.

These changes were the result of the first big Van Gogh scandal. Otto Wacker, a Berlin dealer, contributed a group of paintings to an exhibition held at the Paul Cassirer Gallery, also in Berlin, to celebrate the publication of La Faille’s book—and the Cassirer staff realized at the last moment that they were not by Van Gogh. Scientific tests at the Berlin National Gallery confirmed this visual assessment. There was a sensational trial, at which the leading Van Gogh scholars of the day gave contradictory evidence. Wacker, who never admitted any involvement with forgery, was jailed for nineteen months and fined 30,000 deutsche marks. The pictures are now thought by most experts to have been painted by Wacker’s brother.

La Faille published a second book about Van Gogh’s work in 1930, this time entitled Les Faux Van Gogh. He cataloged the Wacker fakes and another large group of spurious paintings, mostly still lifes, in the style of Van Gogh’s Paris period. Fakes virtually always reflect the style of the period in which they were painted. Identifying the 1920s Wacker fakes is easy today, but the Paris period fakes, which may even have been painted in Van Gogh’s lifetime, are still causing problems.

La Faille reveals that a large number of them, all apparently by the same hand, were owned and sold by Théodore Duret, whom he categorizes as “the erudite connoisseur of Impressionism.” A close friend of Manet, Duret was a critic who keenly supported the avant garde, a collector, and an amateur dealer. He was the rich son of a leading cognac merchant, which allowed him the freedom to dabble in art. But in 1894 the family firm went broke and he had to sell his collection. Thereafter he was frequently associated with fakes—maybe it was how he maintained the lifestyle to which he had become accustomed.

Many of the pictures Duret sold to the great American collectors Henry and Louisine Havemeyer, now in the Metropolitan Museum, have been consigned to storage as misattributions, including works he ascribed to Courbet and Goya. In 1916 the firm of Bernheim-Jeune, who were—and are—publishers as well as dealers, published a monograph on Van Gogh by Duret; it was quickly withdrawn because the authenticity of six of the illustrations was challenged. Duret made many donations to the Petit Palais, including a great portrait Manet had painted of him and a fake Van Gogh still life. And when the remainder of his collection was auctioned at the Hotel Drouot after his death in 1927 a judge ordered that all the signatures should be removed from the pictures before the sale—because the experts considered them fakes.

La Faille mentions a rumor that Duret’s fakes may have been painted by “someone called Murer” and he could be right. Eugène Murer was a pastry cook turned artist who exhibited the paintings of his Impressionist friends in his shop and, after his business failed, retired to Auvers where he got to know Dr. Gachet. Renoir painted a portrait of him. Two still lifes which once belonged to Murer have recently been auctioned as Van Goghs and could turn out to be his work, Thistles at Sotheby’s and a Vase of Poppies at Christie’s (å£250,000 and unsold at $9 million, respectively).

Roland Dorn, again judging on visual grounds, identifies the earliest known Van Gogh fake as a Still Life of Mackerel, Lemon and Tomatoes in the Swiss Winterthur Museum, which is recorded in the 1890s in the stock book of the famous Paris art dealer Ambroise Vollard. Dorn suggests that Vollard, who was just starting out, would have happily sold a picture with the wrong artist’s name attached if he found a buyer who was prepared to pay. The activities of Duret, Murer, and Vollard with respect to Van Gogh have not, however, been the subject of any of the research that has recently been published. The two suspects that the experts are currently arguing over are Emile Schuffenecker and Dr. Gachet.

Schuffenecker’s most admirable trait was his unerring eye for talent among his artist contemporaries—long before the public had caught up with them. At the turn of the century he had the second most important collection of Van Goghs in the world—after Van Gogh’s own family, that is. In all, he put together a collection of no fewer than 120 paintings by Van Gogh, Gauguin, Redon, Cézanne, Filiger, and Emile Bernard. After his wife sued for divorce, he was forced into selling all of them to his wine merchant brother Amédée. By 1903 the transaction was completed and in 1906 Amédée changed his stationery; instead of a dealer in cider, wine, and champagne he was now a dealer in art. German press reports on the Wacker scandal mention that the Schuffeneckers were known at that time for making fakes and, at Amédée’s death in 1936, an artist neighbor noted that his paintings included “some newly made Van Goghs, one of which was guaranteed genuine by Emile Bernard.”

Whether Emile Schuffenecker painted the fakes that Amédée sold has not been definitively resolved. If we accept that the Yasuda Sunflowers is not by Van Gogh, there is a strong case for also accepting that Emile made at least one of them. He is the painting’s first recorded owner and had the perfect opportunity to copy the London National Gallery Sunflowers. He spent several months restoring it for Johanna in the second half of 1900. It is, however, possible that an unsuccessful artist called Judith Gerard also made fakes for Amédée. Born in 1881, she was taught to paint as a teenager by Gauguin and later sold Amédée a copy she had made of a Van Gogh self-portrait—which, according to her memoirs, he sold as genuine. She claims to have signed it “after Van Gogh” but Roland Dorn, who has examined the painting, says that there is no sign of such an inscription ever having existed.

Emile Schuffenecker certainly had the technical skill to make the fakes. He had the rigorous training of a nineteenth-century Salon painter and, according to information given me by Jill Grossvogel, who is preparing the Schuffenecker catalogue raisonné, openly made copies of paintings by Prudhon, Delacroix, Rousseau, Gauguin, and Van Gogh—the Van Gogh Museum has a pastel copy of the famous self-portrait with a bandaged ear which Emile owned.

The Gachet story is also full of unsolved mysteries. Vincent arrived in the little village of Auvers-sur-Oise, on the outskirts of Paris, on May 20, 1890. His brother Theo had arranged that Gachet, who lived nearby and was a specialist on mental problems, would keep an eye on Vincent and help him if there was a recurrence of his illness. They met for the first time that same day—May 20, 1890.

But Vincent’s etched portrait of Dr. Gachet—his only known etching—is dated May 15. Benoît Landais recently found a letter from Johanna to Paul Gachet Jr. written in 1912 commenting on the exhibition of the etching in Germany as a Van Gogh—“I thought it was made by monsieur your father,” she wrote. “I have some copies myself, but have never sold any.”

Louis Anfray, a French researcher, was the first to suggest the etching was a fake in a 1954 article for Art-Documents. By returning to contemporary documents and interviewing survivors, he sought to demonstrate that the Gachets had imposed a fictionalized account of Vincent’s stay in Auvers on the public. Vincent’s own nephew and heir, Vincent Willem, was among those convinced by the argument. Vincent Willem went on to conclude that all eight Van Gogh paintings that Gachet’s son had given to the Louvre were also fakes “except, possibly, the painting of the church in Auvers and the face of the self-portrait with the waving lines in the background.” Among the paintings he dismissed as fakes was the famous Portrait of Dr. Gachet now in the Orsay. Baart de la Faille, who collaborated in Anfray’s researches, also came to the conclusion that the Gachets had launched a series of Van Gogh fakes on an unsuspecting world.

Vincent’s first impression of Dr. Gachet was “un drôle de bonhomme”—an odd creature. As they got to know each other better Vincent decided that Gachet’s eccentricity verged on mental illness. “It seems to me that he is iller than I am, or at least—as sick,” he wrote to Theo. Gachet had only minimal qualifications as a doctor; he took up painting as a student and fancied himself a printmaker—he had his own etching press in Auvers. His dark little house, nestling against the steep incline of the hill, was packed with a miscellany of paintings and objects like a junk shop. “You will see what his house is like,” Vincent wrote to Theo. “It’s full up, full like an antique shop with things that are not always interesting. It’s really terrible.”

Gachet was then a widower, sharing his house with his two children, Marguerite, twenty-one, and Paul, seventeen, their old governess, and an indigent lady called Blanche Derousse, the daughter of a friend. Gachet taught both Blanche and his son Paul to paint. The paintings which emanated from his house that are now suspected by Landais and others of being fakes—which include Cézannes as well as Van Goghs—could have been made by Dr. Gachet himself, though marketed and introduced to the world by his son Paul. But it is also possible that Blanche Derousse may have made them. Nothing is known of her history apart from a glancing reference in Paul Gachet Jr.’s biography of his father.

Several of her small etchings after Van Gogh paintings have survived and display great skill. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam has two which she very carefully painted over in watercolors. One of them is a repetition in miniature of a Van Gogh painting known as Les Deux Enfants that Paul Gachet Jr. gave to the Louvre. A second version of this subject, also believed to be by Van Gogh, is now in a private Greek collection. The Derousse watercolor appears to contain elements of both versions; it is possible that she copied the genuine Van Gogh in miniature, then copied her own miniature in oils to create a second version. Blanche died, one year after Dr. Gachet himself, in 1910.

Vincent’s nephew, Vincent Willem, bought the two Derousse watercolors now owned by the Van Gogh Museum and became convinced that she was the author of fakes that had been presented to the world by Paul Gachet Jr. In a 1966 letter to the board of the Van Gogh Foundation he wrote: “I am convinced now that Blanche Derousse made paintings which passed as paintings by Van Gogh. I have no grounds to believe they were made for this purpose. She died at the beginning of this century and presumably Gachet sold them as Van Goghs.”

Paul Gachet Jr. was even more eccentric than his father. He never had a job but lived in his father’s Auvers house with his sister and his wife, selling inherited pictures and objects from time to time. He dressed like his father, even wearing his old overcoat, and eventually became a recluse. He would only receive art historians to whom he told bombastic tales of his friendship with Vincent—mostly untrue. Starting in 1949 he made a series of donations to the Louvre and other museums; it was his only claim to importance and won him the Legion of Honor. He gave a very precise copy of the Garden of the St. Paul’s Hospital to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which Vincent Willem believed to be a fake. With Gachet, as with Schuffenecker and the other suspects, long and careful investigations are still required before we can hope to know the truth. Meanwhile the number of suspect Van Goghs is steadily mounting.

This Issue

February 5, 1998