Sedgwick Clark, the producer of New York Philharmonic: The Historic Broadcasts, 1923-1987, tells us that the album’s twelve hours of recorded music were chosen by him after listening to “hundreds of hours of live music-making.” But since he provides no information about the selection process and the winnowed options, the other choices that had been under consideration, critical comment on these subjects is limited to guesswork. Ultimately the discussion of repertory is lowered to the level of “de gustibus….”

Clark does reveal that he and Kurt Masur, music director of the New York Philharmonic, decided to restrict the contents of the records to broadcasts, Masur being “keen on preserving the spontaneity of live performances.” But so far from all or even most live performances generating much feeling of spontaneity, a high proportion of them are moribund, and not a few altogether brain-dead. What they do guarantee are distractions resulting from bronchial disorders, the crepitations of program page-turning, the shifting of positions in seats, and other extraneous noises, as exemplified in varying degrees in all ten of the album’s CDs. Studio recordings, on the other hand, demanding at times greater intensities of sustained concentration, have been known to convey a high sense of the naturalness and the unprompted instinctiveness that define spontaneity. But all of this seems beside the point, which is that the live broadcasts, thanks in part to coughs, etc., give the listener the sense of being there.

Another Masur precondition was that “only conductors no longer active on the podium”—i.e., not alive—“would be considered.” The reason for this mandate is withheld, however, perhaps because Masur himself, of the three maestros to whom it applies, did not wish to participate. One suspects, too, that Rafael Kubelik (who died in August 1996) was still among the quick when his unsurpassed performance of Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle was nominated for inclusion, since this, the longest piece in the album, alone accounting for one of the twelve hours, is not likely to have been a last-minute choice.

The selection of conductors and soloists seems to have taken precedence over the selection of repertory, as, in some cases, musical politics has over music. Of the twenty-one conductors represented, Bruno Walter is given the lion’s share of performing time. He and Toscanini have entire discs to themselves, but Walter has a substantial part of another one as well. The absence of Wilhelm Furtwängler is thus all the more glaring, since he and Toscanini were the chief contenders for the position of music director in the late 1920s, and no one, I think, would rank him below Willem van Hoogstraten, André Kostelanetz, Josef Krips, Erich Leinsdorf, and John Barbirolli, who do appear. The debate about Furtwängler’s wartime career in Germany can hardly have been an issue in this decision, since Willem Mengelberg, an ardent Nazi sympathizer, is included. Oddly, the conductor Karl Böhm, an out-and-out Nazi, is referred to glowingly in the album booklet’s abbreviated history of the orchestra, while Furtwängler, who had a major part in its musical development, is nowhere mentioned.

The account of the early years in the aforesaid neglects to explain why Walter Damrosch’s New York Symphony Society and not the Philharmonic was chosen for Carnegie Hall’s baptismal concert in 1891, which was partly conducted by Tchaikovsky. Nor is anything said about the Philharmonic’s connection, a little later in the 1890s, with Antonin Dvor?ák, who was teaching in a New York conservatory. The then director of the orchestra, Anton Seidl, with whom the Czech composer became friendly, reawakened his interest in Wagner, while an 1894 Philharmonic performance of the second of Victor Herbert’s cello concertos inspired Dvor?ák to write his own still- popular one.

The Orchestra’s beginnings are dim. It gave three concerts in the inaugural season, 1842. By 1875-1876, thirty-three years later, the number had increased by only three. Still another thirty-three years were to pass before the total had risen to eighteen, and not until Gustav Mahler became principal conductor, in 1909, had it expanded to fifty-four. But Mahler died after his second season.

Josef Stransky followed him, and was followed in turn by Mengelberg, in whose nine-year reign Stravinsky, Toscanini, Furtwängler, Klemperer, and Erich Kleiber were the principal guest conductors. In 1930, Toscanini was appointed sole conductor, and the period until he retired in 1937 is recognized as the Orchestra’s golden age. The unenviable position of successor fell to the young, little-known Englishman John Barbirolli, whose incumbency, as must have been foreseen, provoked controversy and discontent. The generally praised Artur Rodzinsky took over during the war years, with George Szell and Bruno Walter prominent as guest conductors. Walter was named “musical adviser” in 1947, and two seasons later Leopold Stokowski and Dimitri Mitropoulos were designated “joint-resident” conductors, an unsatisfactory arrangement that led to Stokowski’s resignation after only a few weeks.

Advertisement

Mitropoulos’ nine subsequent years with the orchestra are generally seen as troubling. The former Greek Orthodox ordinand, the most phenomenally gifted performing musician of his time, was too gentle and forbearing in his relations with the players. Discipline declined, and eventually so did artistic standards. His programs—Mahler symphonies, concert performances of Strauss’s Elektra and Berg’s Wozzeck, Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra, Orchestra Variations, Erwartung, and A Survivor from Warsaw—were too progressive for Philharmonic subscribers. Moreover, Virgil Thomson’s famous description of his contortions on the podium is cruelly accurate: “He whipped [the orchestra] up as if it were a cake, kneaded it like bread, shuffled and riffled an imaginary deck of cards, wound up a clock, shook a recalcitrant umbrella, rubbed something on a washboard and wrung it out.”

Perhaps, too, his incredible memory unnerved the players. The booklet quotes John Shaeffer, a member of the orchestra’s bass section: “Mitropoulos did the whole season without using a score, rehearsals as well as concerts….” Schoenberg disapproved of this: “…In my Society for Private Performances in Vienna I did not allow playing from memory. I said: ‘Our musical notation is a puzzle picture which one cannot look at often enough in order to find the right solution.”‘ But Mitropoulos was reading photographically memorized scores, not simply following melodic and dynamic contours as others do who conduct “by heart.” To demonstrate how a passage should sound, or expose wrong notes, he would go to a piano and, as this reviewer observed at the conductor’s rehearsals of Schoenberg’s Serenade, play music of the greatest harmonic complexity for which no piano arrangement existed. Mitropoulos is represented in the Historic Broadcasts only in the ungrateful role of accompanist, to Francis Poulenc in his Concert champêtre, and to David Oistrakh in Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto. In 1958, two years before Mitropoulos’ premature death, he abdicated in favor of his competitive friend Leonard Bernstein, who survived in the glamorous but gory arena for eleven years.

Among the album’s many outstanding performances, the greatest is the Brahms Violin Concerto played by Jascha Heifetz and Arturo Toscanini in 1935. In the more than six decades since the broadcast, and in spite of all the interim improvements in recording technology, the allure of the young Heifetz’s tone has not been surpassed even by himself. As performed by him and Toscanini, the music takes possession of the listener’s imagination and will not let go. No matter that in two or three places in the first movement the violinist takes off in his own, slightly faster tempo, nuances of speed that contribute to the excitement: Toscanini is never left the smallest fraction of a second behind. In the interests of intonation, Heifetz occasionally substitutes harmonics, an old trick of his, a gross solecism in his commercial recording of Mozart’s A-major Concerto, but smoothly blended and scarcely noticeable here. Arriving slightly flat on a high note at the end of a run, Heifetz instantly adjusts the pitch in a way that makes the tiny miscalculation sound like an attractive planned effect. One almost suspects that the raggedness of the orchestra’s descending string-triplet octaves twenty seconds or so before the end may have been deliberate, to show human fallibility.

Coughs could be complained about, but they are rarer here than elsewhere in the set. Other incidental noises include what sounds like a muffled revolver shot during the cadenza (the suicide of an aspiring violinist?), and two notes from what could be the timpanist tuning up during the second bar of the second movement.

Brahms’s Second Symphony also receives a first-rate performance, conducted by Fritz Reiner, its second movement at the perfect tempo, the first and third at only slightly less than that, although the fourth is rushed. Brahms, represented by two of his strongest pieces, as Mozart and Beethoven are not, is thus the album’s winning composer. (At lunch one day in the Hotel Berkeley, Paris, in the late 1950s, Françoise Sagan, attractive, intelligent, chic de la chic, asked to be introduced to Stravinsky and came to his table. He said, “Enchanté. Oui, j’aime Brahms,” and explained that like him, he wanted more than anything to be worthy of the past.)

What will baffle musicians and others is the repertory of the collection: no Haydn, though his symphonies and Masses were Bernstein’s forte; no mighty Beethoven, unless I am mistaken about the stature of the C-minor Concerto; and no Schubert, no Schumann, Weber, Berlioz, Liszt, Dvor?ák, or even Mahler—but in his place a great Bruckner Ninth by Otto Klemperer, almost hidden under surface noise like frying bacon. Mozart is represented only by early pieces, the Three-Piano Concerto, “accomodati” for two pianos by him, but from which, delectable as it is, not much stays with the listener; and the marvelous A-major Symphony, but in a punchy, string-heavy, and poorly articulated performance. Since Italian music is entirely absent, one supposes that a token Verdi or Rossini overture under Toscanini’s magic wand was not available, but, then, the stunning La Mer, conducted by his tragically short-lived protégé, Guido Cantelli, is more “Italian” than “Gallic.”

Advertisement

Some presences are likewise inexplicable. Sir Henry Wood’s bombastic arrangement of Bach’s D-minor Toccata and Fugue is out of place here, as, for a different reason, are the arias from Fledermaus. The two “fragments”—shellac* “shards” describes them better—from Mengelberg’s 1924 performance of Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration are merely frustrating. They were included, no doubt, to extend by a decade the time frame, 1923-1987, claimed in the album’s title, since nothing else is offered from the years between 1924 and 1934. The present reviewer would not have included Poulenc’s Concert champêtre and Fauré’s Requiem, the latter apparently intended as a homage to Nadia Boulanger, the composer’s pupil—as, later, she was nearly every American composer’s teacher—who conducts it, but the music is dull and orchestrally subfusc. William Walton’s Capriccio could go, too, as could Strauss’s family-portrait tone poem Symphonia Domestica (magisterially conducted here by Bruno Walter, though it was a Mitropoulos warhorse), and Stokowski’s version of Mendelssohn’s “Scottish” Symphony—the second movement nearly twice as fast as the New York City Ballet dances it—which is too well known for such an album. “De gustibus….” One’s feelings are more ambivalent about the first Chopin Concerto, a non-piece orchestrally speaking, but how otherwise would we hear Artur Rubinstein play the krakowiak? Salome’s Dance, despite Toscanini’s electrifying reading, and En Saga, ditto, could have been omitted. Sibelius repeats his themes too many times, and his relentless rhythms go on throbbing in the head too long.

No milestone twentieth-century music is included. Something by Schoenberg had to be, of course, and the Ode to Napoleon is an astute compromise, sidestepping the historically important pieces, yet conveying the intensity and temperament of the composer’s later work. The music itself, for those who think they don’t like Schoenberg, is partly obscured by the drawled recitation of Byron’s repetitive poem. One of the surprises of the set is Leonard Bernstein, no advocate of the Schoenberg school, conducting Berg and Webern. He does it well, but the high level of audience noise during Webern’s very short Symphony (which closely follows the present reviewer’s 1957 recording)makes it difficult to hear. The applause is much less vociferous.

How was the virtual absence of Stravinsky justified? Certainly the four-minute Fireworks, half Rimsky-Korsakov, half Paul Dukas, does not adequately represent the composer who revolutionized the language of music itself. The likely reason for the absence of the Symphony in Three Movements, commissioned by the Philharmonic, which also broadcast its premiere, is that the solo cello in the middle movement in the broadcast plays in the bass rather than the tenor clef. But why was the April 7, 1940, broadcast of The Rite of Spring excluded? This musical earthquake, universally regarded as one of the century’s crowning masterpieces, would have provided measurements of the orchestra’s ability to master difficult new rhythmic and other idioms at a time when the piece was seldom heard. Perhaps the broadcast performance does not bear comparison with the studio recording, made the next day, which does great credit to the Philharmonic. (Sedgwick Clark, an affable fellow, once told this reviewer that a recording of the Rite converted him to “classical” music, which could happen again to others.) Unlike the Rite, Strauss’s Domestica testifies to no more than the orchestra’s powers of endurance.

The exact same time that might have been allocated to the Rite is occupied by Stravinsky’s recording of Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony from that same 1940 broadcast. The fleet-footed execution employs the neatest string—or, rather, off-the-string—staccato articulation on any of the ten discs. But the charming, elegant music is also minor, and other broadcast recordings of Stravinsky’s interpretation are available. His authentic performance of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sadko tone poem, taped on January 17, 1937, would have represented the later Russian Nationalist school, otherwise almost neglected.

Charles Munch’s debonair, sprightly Afternoon of a Faun is a happy resuscitation, a welcome change from the carnal interpretation popular nowadays, which overemphasizes the molto crescendo in the D-flat-major section, traditionally supposed to have been coordinated with Nijinsky’s scandalous “ejaculation.” Munch inadvertently picks up speed, however, while switching away from subdivided beats in bar 17.

Bartok’s Bluebeard is the lone representative of pre-World War I musical modernism. One lauds the choice partly because it is a risky one, a theater piece, dependent to a degree on visual tie-ins of lighting and color symbolisms, an opera sung in Magyar, in untranslatable (an English text is provided) octosyllabic lines, and lugubrious in mood. Confined to the slow-moving dialogue of Bluebeard and his last wife, Judith, the work lacks action, and yet attains great dramatic intensity as Judith’s inquisitiveness gradually turns into jealousy.

The music is also static, consisting largely of a chain of ostinatos, most of them too long. Yet the score contains wonderful things, beginning with the characterization of Bluebeard in his singing, or speaking, by simple rhythms and modalities, and of Judith by lighter, three-meter music, at least in the first part, and by glittering orchestral adornments. But the orchestra is paramount, a performance in piano reduction unimaginable. The instrumental timbres and their combinations are original and masterful. No other modern composer has employed the organ in an orchestra with such skill and to such majestic effect. Bartok’s use of dissonance is no less remarkable. The minor second is to Bluebeard what the major second is to Petrushka, another masterpiece completed in the same year, 1911. Clark rightly observes that the jump from Debussy’s Faun into Bluebeard, which follows in the album, is not so precipitous, but Pelléas et Mélisande, not the Faun, is Bartok’s musical model, especially in the chant-like vocal style. The Bluebeard in this performance has the requisite range of Pelléas’s Arkel at the beginning, and of Golaud later.

The album’s two most recent specimens of twentieth-century music are Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto (1954) and John Corigliano’s Clarinet Concerto (1977). Whereas Clark’s experience of the former was “searing,” this reviewer derives no calefaction from it whatever. The steady-beat, largely on-the-beat music is rhythmically monotonous throughout, whether in the turgid passacaglia or the lickety-split scherzo and two-four finale, and the alternation of fast and slow is routine and stale. The opus is devoid of engaging musical ideas, its brand of key-signature tonality is without harmonic interest, and the whole is academic to the extent that the cadenza sounds like a conservatory exercise. The coughing spells are enlivening.

The choice of the Clarinet Concerto must have been a difficult one, given the size of the American composers’ lobby. The music touches base with prevalent styles and gives the percussionists and sound engineers their heads. But never mind. It attains Corigliano’s goal: “I wish to be understood. I think it is the job of the composer to reach out to his audiences with every means at his disposal. Communication should be a primary goal.”

Still, we are indebted to Sedgwick Clark for having collected so many great musical performances. The peak of his achievement, however, and a very high one, is in his brilliant juxtapositions. One record is devoted to French music, another to Austrian, but beyond that, cultures, periods, musical forms, genres, and soloists are mixed with the greatest success. What the records establish is that the coast-to-coast Sunday matinee broadcasts by the New York Philharmonic in the 1930s, 1940s, and even beyond set the highest standards of symphonic music performance the country has ever known; that the distraction of radio static is insignificant compared to the camera’s close-up of blowing and bowing players and mugging maestros in the idiocy of today’s television concert, and that for at least thirty years this New York orchestra was, and again may be, number one in the world.

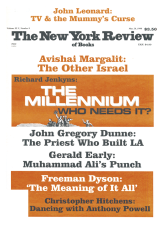

This Issue

May 28, 1998

-

*

Shellac pressings were made from electroplated wax masters.

↩