Speaking at the grave of Galina Starovoitova after she was murdered in St. Petersburg on November 20, one of the Russian mourners recalled that terrorism in Russia is nothing new. But the nineteenth-century terrorists, so perspicaciously depicted by Dostoevsky in The Possessed, terrible as they were, had a certain ethics: they paid with their own lives for taking the lives of their enemies. The terrorism of today’s Russia is a work of cowardly bandits who are interested in nothing but money, whether they are doing the bidding of politicians or not. Authorities don’t know how to deal with this criminal Mafia. “No one among us expected,” concluded the speaker, “that the road to freedom would be so difficult.”

1.

She belonged to a generation that did not dare to dream that freedom would come. When freedom did come, she placed her faith in it with all the strength of the naive romanticism of a Russian intelligent. She was one of the charismatic leaders of the first generation of perestroika. She contributed greatly to the demolition of the Soviet prison of nations, and added her brick to the construction of the edifice of Russian democracy. The Russian intelligentsia, long deprived of freedom, savored its intoxicating taste. They were aware that in the fight for freedom there is a price to be paid. This is why Russia gave birth to a generation of courageous and noble people. But freedom is for everybody—also for rascals, cheaters, and hooligans. When freedom is young, and not yet solid, it is always accompanied by an undeclared war between the idealist, who strives for truth and honesty in public life, and the gangster, who is satisfied with the freedom to rob. Galina Starovoitova fell victim in such a war.

What is Russia? “A limitless plain, austere climate; austere, gray people with its heavy, gloomy history; tartardom, tchin, ignorance, poverty, humid climate of the capital Russian life batter the Russian so that he is unable to collect himself, batter him as if with a thousand-pound ram.” This is how, a hundred years ago, Anton Chekhov wrote about his country.

I liked Galina Starovoitova, a direct and cheerful woman, friendly toward the world. We met in the summer of 1989, when I visited Moscow for the first time. It was a year when the world was in ferment and the sky over the Soviet Empire was trembling. The impossible was becoming possible and even banal. The most romantic prophecies turned out to be real as if they had been the most obvious predictions. Galina-“Gala”-came to a meeting of university students at which I was speaking about Poland, the Polish democratic opposition, the Workers Defense Committee-KOR, and Solidarity. After the meeting, this nice, golden-haired woman came up to me, introduced herself, and proposed going to dinner. We passed the evening in her room, provided to her in her capacity as deputy to the Highest Council of the Soviet Union, talking about Poland and Russia, dictatorship and freedom, Gorbachev and Jaruzelski, Yeltsin, Sakharov, and Walesa. In the ensuing ten years, we had many similar conversations in Moscow and Rome, Paris and Japan, Switzerland and the United States, and in Italy. When we spoke for the last time in Moscow, Galina told me that she planned to give me photos from our excursion in the canals of Venice, with my little son Antos. I had no time to pick up these photos, in which we were sitting in a Venetian vaporetto, laughing and happy that fate allowed us such moments. Most probably, I will never pick up these photos, and will never again be able to enjoy so much that recovered freedom.

2.

The year 1985, when the general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Konstantin Chernenko, was dying, was a period of bleak helplessness. For many years, Russia had been governed by a group of stolid old men. The members of the dissident movement seemed defeated: some tried their luck in exile, others were dying in camps. It seemed that there was no hope. And then, from the new general secretary, Mikhail Gorbachev, came the words that soon were known worldwide: perestroika, uskorenie, glasnost—reconstruction, speeding up, transparency. These words provoked fright, distrust, and hope. The fright was in the men of the apparat, whose seats were shaking beneath them; the distrust was among the hardened émigrés, who saw in these words a shrewd and deceitful move by the Communist power; and hope was awakened among the intelligentsia, which for a very long time had been drowning their gloom in the glasses of vodka drunk in the kitchens of Leningrad and Moscow. Gala Starovoitova was among the first ones who decided to place their faith in hope. She was a cultural anthropologist by profession and a typical Russian intelligent by temperament. An intelligent, I would emphasize, not a politician, although it was her involvement in politics that brought her fame and death at the hand of a hired murderer.

Advertisement

In Russia, “under the banner of science, art, and persecuted freedom of thought such toads and crocodiles will come to power as did not exist even in Spain in the times of inquisition. The narrowness of concepts, big pretensions, excessive ambition and a complete lack of conscience have consequences. Every charlatan and wolf in sheep’s skin will be able to freely lie and deceive.” This, again, is from Chekhov, written a hundred years ago.

The leaders of the first wave of perestroika did not understand politics— its games, mechanisms, and brutal cunning. They understood, however, what conscience is. Instinctively, they accepted as their own the system of values and the way of thinking of Andrei Dmitriyevich Sakharov, a great physicist, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, defender of human rights, and prisoner of conscience, who was able to turn defenselessness into strength. It was he, the inheritor of Herzen and Chekhov, the most excellent and noble incarnation of the best characteristics of the Russian intelligentsia, who became a spiritual leader of all those who were not satisfied with praising Gorbachev and who were trying to turn Russia into a democratic state. Their principle was the truth; their characteristic was straightforwardness; their method was a nonviolent way of forcing change; their spiritual climate was free from hate and thoughts of revenge.

They were the first to reject not only the party nomenklatura and Bolshevik ideology but also Russian nationalism and devotion to empire. At the beginning they met at the club “Moscow Tribune,” then in the parliamentary Interregional Group. They spoke about the dramatic conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia, about the pogroms in Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan, about the bloody events in Georgia. It was they who condemned the massacre of Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Gala first gained great authority through her work in defense of persecuted Armenians. In the months before the putsch of General Yanayev in 1991, she tried to mediate between Gorbachev and Yeltsin. At the time of the putsch, she was on the side of democrats, which did not surprise anyone.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Gala was an adviser to Yeltsin on the question of nationalities. Did she advise him well? I am not sure. The national question in the Russia of that time was like a tangled, bloody knot, which no one knew how to disentangle. Gala believed deeply that Russia had to shed its cloak of imperialism. She believed, after Herzen, that a nation that oppresses other nations couldn’t be free. This is why she was ready to support all those who demanded sovereignty.

Yet the matter was not obvious. The Bolsheviks in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan transformed themselves into Asiatic potentates. A dissident and former political prisoner, chosen as a president of Georgia, became an authoritarian despot, who started to put in prison his former friends from the democratic opposition. For Gala, however, they were all simply fighters for freedom from Soviet domination. Only a few years later did I hear from her a slightly different view. She spoke about the responsibility of the former colonizer for the shape and the trajectory of decolonization. She was not sparing in her criticism of her own illusions. She saw clearly that it is not enough to be against Moscow in order to earn the name of democrat and the respect due to one. But she never joined those who replaced the rhetoric of democracy with the rhetoric of empire. I remember her sharp dispute with a Turkish politician in which she argued on behalf of the Kurds, and I remember her public polemics with Russian nationalists who loudly condemned the discrimination against Russians in the Baltic States. To both Galina responded with straightforward courage but without any political cunning.

Can someone with such a character have a career in politics? The leaders of the first wave of perestroika became more and more marginal. The winning side belonged to the spirit of shrewdness, of gamesmanship, of financial foresight. Those who were less opportunistic—the intelligentsia rejected by the world of politics—were facing a dramatic choice. If they decided to participate in power, they had to pass between Scylla and Charybdis—between turning into classic, unprincipled apparatchiks and risking physical extinction. Galina often said that I was right to resign from politics in order to edit a newspaper. She herself understood her political activity as an ethical duty. Often she felt discouraged by the strange Vanity Fair that politics had become in post-Communist countries, especially in Russia.

For Russians everyday life came to be very difficult, with its unemployment, poverty, criminal scandals and corruption, demagogy, the feeling of being lost among empty words, and the fear of tomorrow. The Russian democrats were unable to create a force that would lead the state through the difficult turning point of economic shock therapy. They slipped into quarrels, conflicts, plots. People with very different ideas appeared on the scene: national Communists or national fascists. They became ever more strong, while the democrats weakened. And the democrats themselves more and more often reached for nationalist and imperial slogans. The history of Russia knows such turns in public opinion. One hundred and thirty years ago Russian opinion became fascinated by the reforms of the tsar Alexander II, and the main source of intellectual authority was the thought of the democratic thinker Alexander Herzen. But the beginning in January of 1863 of the Polish insurrection caused a change in the Russian intelligentsia: Herzen, who was sympathetic to Polish aspirations, was forgotten; his place was taken by the imperialists who favored drowning the Polish insurrection in blood.

Advertisement

Now, one hundred and thirty years later—after the bloody conflict in Chechnya and the polemics against the enlargement of NATO—the slogan of the Great Russia chauvinists is “the defense of Serbian brothers.” Christian Orthodox and Slavic connections are invoked. From the Russian parliament, we could still hear from time to time the clear and honest voices of Galina and of the human rights activist Sergei Kovalev, but we heard more often the rattle of the contemporary “Black Hundreds.” Lies and calumny overflowed the Russian parliament. And lies, Chekhov said, are like alcohol. Liars lie even in the face of death. And when in Chechnya young boys were dying, both on the Chechen and on the Russian sides, in the Russian parliament we constantly heard from nationalists that the democrats who objected to the war had betrayed Russia. A few days before the assassination of Galina, the Russian national Communist Makashov openly called for anti-Jewish repression. And as usual it was not the Jews who were the main target. They were at most a bait for the mob. The target was Russian democracy and Russian democrats, such as Galina Starovoitova.

It does not make sense to summarize in detail the ideas of contemporary “Black Hundreds.” As they understand it, the division in Russia is simple. On the one hand there is the worldwide Jewish Mafia and its democratic agents in Russia. On the other, the patriotic movements: Russian national Communists and Russian Orthodox-monarchist patriots. The “Black Hundreds” reject the West as the seat of evil and the ruin of Russia. This is why they aim at the annihilation of Russian democracy, in which they see the fifth column of Western civilization.

3.

The democratic camp in Russia is weak and internally divided. The epoch of Yeltsin is ending. He was a politician who transformed Russia, although we still don’t know to what degree he did so for good or for bad. Yeltsin, an apparatchik from Sverdlovsk, became for a time a charismatic leader of the masses that did not want the Bolshevik power anymore. And the same Yeltsin became an object of mass hatred when he did not know how to fulfill the Russian hopes for a miracle, when he did not know how to curb the growth of the Mafia, when he marched into the tragic war with Chechnya. Yeltsin did not know how to build a coalition with democrats, who continuously split into new parties led by new leaders. In the last parliamentary elections, there were so many of these parties that only a few passed the threshold of 5 percent of the vote. And in the presidential election, there were so many democratic candidates that it created a rather grotesque impression. Among those contending for the presidency was also the first leader of change, Mikhail Gorbachev. He received less than one percent of the vote. This is the post that my friend Galina Starovoitova also hoped to run for. I don’t believe her showing would have been better.

Will Russia find a place for itself in the twenty-first century? Galina was convinced that it will. She believed in democratic Russia because she loved her country and believed, in the words of the nineteenth-century philosopher Pyotr Chaadayev, that one cannot love one’s country with a blindfold over one’s eyes and a gag over one’s mouth. Galina believed that the Russian nation would not allow itself to suppress another nation, would not succumb to anti-Lithuanian or anti-Ukrainian or anti-Polish hysteria. She wanted a Russia that would be able to take upon itself some of the responsibility for what was done in its name and by the hands of its representatives in the other republics within the Russian Federation, or the countries outside it. She never looked for false justifications by blaming the foreigners for Russian faults; but she always defended Russians facing injustice.

A sudden death by assassins imposes a different perspective on an entire life. It is like a sieve that separates the things that are essential from those that are not. Such a death reminds us of the need to live in the circle of final questions—the final judgment steadily faces us and the sentence may be pronounced at any moment. There is therefore an imperative to live in such a way as to be able to look without shame into the eyes of what is final. There are people who live in order to kill. Such are Galina’s assassins and their masters. And there are people who live to help others to live, and they are sometimes killed because of that. Galina Starovoitova was such a person.

—Translated from the Polish by Irena Grudzinska Gross

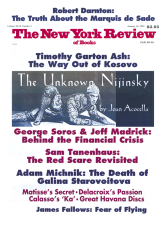

This Issue

January 14, 1999