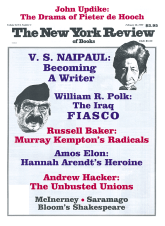

Pieter de Hooch, though often cited as a painter of domestic Dutch scenes, was never the exclusive subject of a show until one this fall, which enjoyed record-breaking attendance in its ten weeks at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery before coming, with the winter, to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. His reputation has long been associated with that of his contemporary Vermeer. When in 1765 a painting of his was offered for sale in Amsterdam, it was described as “zoo goet als de Delfze van der Meer“—“as good as Vermeer of Delft”—and the nineteenth-century French critic Théophile Thoré, in reviving Vermeer’s reputation, attributed to him five paintings by de Hooch. It is true that both painters portray intimate domestic interiors of a modest scale and quiet mood, but de Hooch suffers cruelly from the comparison. His brushwork is scratchy, his colors brownish and murky, and his compositions haphazard when viewed with Vermeer’s pellucid and exquisitely rigorous canvases in mind. Compared with Ver-meer, de Hooch does not draw well, let alone paint with the younger man’s serene rapture of weightless touch and opalescent color.

For Vermeer, as for very few artists prior to the Impressionists, painting is not just the method but the subject, a topic explored in such dazzling visual essays as the reflections on a brass water pitcher and basin, the shadows falling across the shallow ridges of an unscrolled map, the photographically exact yet rather freely brushed pattern of a folded and foreshortened Oriental rug, the liquid spill of a lacemaker’s red and white threads, the cool folds and dimples of a silk skirt, the delicately muted and flattened colors of a picture on a wall—a picture within a picture to tell us that this too is a picture. The science of perspective and the invention of the camera obscura opened to Vermeer, in this era of burgeoning astronomy and microscopy, a world of optical truth to which both the painter and his human subjects are in a sense transitory visitors, accessories to the transcendent process whereby light defines objects.

With de Hooch the topic is less the seeing than what we see—homely Dutch folk and their furniture, their rooms, the cityscape glimpsed over their shoulders. Thirty-eight of his paintings fill two big rooms of the Wadsworth (it and the Dulwich Gallery, the catalog proudly points out, are equally venerable—“the first public museums to open in their respective countries”) and they reveal not only where de Hooch falls short of Vermeer but where he goes beyond him, providing what Vermeer in his great rarefaction does not. Children, for one thing. Though Vermeer had at least eleven, not a single child appears in a painting by him, perhaps because children could not remain still long enough.

On the other hand, a high proportion of the de Hooch canvases on display at Hartford contain children—a bit stiffly and incidentally in Mother and Child with a Serving Woman Sweeping (circa 1655-1657), Two Women and a Child in a Courtyard (circa 1657- 1658), and A Woman and Child in a Bleaching Ground (circa 1657-1659; see illustration on page 12), and with an affecting tenderness and concentration in Woman and Child in an Interior (circa 1658) and A Woman with a Baby in her Lap, and a Small Child (1658). The tiny hands in the latter—the baby’s curled in drowsy relaxation on its mother’s lap, the child’s grasped around a complaisantly limp lap dog—are painted with a tactful skill de Hooch brought rarely to human anatomy. The sunlight caught in the backlit woolly hair of the child in The Bedroom (circa 1658-1660) is one of de Hooch’s most admired effects, tellingly enlarged in the catalog, and A Mother and Child with its Head in her Lap (circa 1658- 1660), showing the mother searching her docile child’s head for lice, is one of his most loved and atmospheric interiors. He does not let us forget that a focus of these cozy, clean, sun-washed Dutch interiors is the nurture and protection of children; it is their pets and toys (including a colf club and ball) that interrupt the swept severity of the tile floors.

All these paintings—and the bulk of de Hooch’s best—come from the period when, by the spotty records, he lived in Delft. Born in Rotterdam in 1629, he learned and practiced his trade there until his marriage to a Delft woman in 1654 cemented his move to that city, a venerable and economically declining center of tapestry ateliers, breweries, and Delftware factories. This modest town of 20,000 people housed, during the 1650s, a boom in genre painting, including such artists as Gerard ter Borch, Carel Fabritius, and Jan Steen, as well as Vermeer and de Hooch. Though no records remain of interactions between the latter two, it seems unlikely that in circles so small there were none. De Hooch, three years older, may have influenced Vermeer to turn from the large mythological subjects of his earliest canvases to smaller-scaled realism. Around 1660 de Hooch moved from Delft to the metropolis of Amsterdam, where the patronage was richer and his paintings became more elaborate and ostentatiously refined.

Advertisement

But while in Delft he captured qualities excluded from Vermeer’s paradise of jewellike moments. The son of a bricklayer, de Hooch gives us the textures underfoot. The floor tiles, arrestingly smoothed to a pattern of alternating black and white in Vermeer, in de Hooch paintings wear their uneven glazing, their raised edges catching the light. His bricked courtyards have the slight wave of uneven earth beneath, and his whitewashed walls bear cracks and rough patches. When de Hooch gets to Amsterdam, he exults in walls of gilt leather, whose embossed and glinting arabesques, in such ambitious canvases as A Party of Figures around a Table (circa 1663-1665) and Merry Company (circa 1663-1665), all but overpower the rather pallidly projected merry companies.

The human figures in the Amsterdam pictures in general lack the warmth of individuality, as if he did not know them the way he did his neighbors in Delft; he visits their houses as a social inferior and is encouraged to focus on their conspicuous possessions. A Seated Couple with a Standing Woman in a Garden (circa 1663-1665) strikingly highlights the sunstruck façade of a small Amsterdam house—brick by brick and pane by pane, vivid as an architect’s projection—and leaves the tête-à-tête in shadow and its flirting couple virtually faceless. De Hooch’s sense of human drama is vague and elastic enough, frequent pentimenti reveal, to permit him to paint people in and out quite late in the stages of composition. In A Woman Drinking with Two Men, and a Serving Woman (circa 1658), the serving woman was added to fill the unpopulated right half of the canvas after the completion of the floor tiles, which show through her feet and skirt; in A Music Party in a Hall (circa 1663-1665) a black servant attending a viola da gamba player was painted out, leaving a wineglass being passed between them suspended in an awkward toast. Even if de Hooch did not execute these later revisions, something unresolved in his initial composition opened the way for the muddle. Some of his figures have a Magritte-like air of floating disconnection. The viewer is frequently struck by vacuously dark stretches in his canvases, whose occupants seem semi-lost in spaces too big for them.

Perhaps space is the secret topic that concerned de Hooch. If Vermeer was the much superior director of human drama, even when only one woman is on the canvas, de Hooch gives us an aspect of Delft that Vermeer, save in his two great cityscapes, reduces to a creamy light evenly streaming through a window: the outdoors. De Hooch’s sunlight is tawny, one with his orange tiles, baked bricks, and varnished cabinets. He takes us out into the paved courtyards where much of Delft’s domestic work was done; he shows us a dirt alley blanketed with laundry (A Woman and Child in a Bleaching Ground) and depicts the makeshift wooden sheds and lattices that pieced out this city of brick and tile (A Courtyard in Delft with a Woman and Child, 1658). Further, his interiors have long perspectives, one room opening into another where a window in turn affords a glimpse of sunlit scenery. The two of his paintings with children already mentioned as most affecting share this layout, and in the slightly later Bedroom the interplay between outdoor and indoor illumination approaches the virtuosic. There is the child’s hair and figure, backlit by the daylight of a vista seen through two doorways, and there is a tawny double window on the left, illumining the mother on the left, planting a rectangular highlight on a chamberpot at her feet, and drawing a trapezoidal shadow from the painting above the doorway. The watery band of light—a ghost refraction—thrown diagonally through the window is well observed, and possibly never before registered in any painting.

The sense of healthy interchange between outdoors and in, between leafy growths and buffed artifacts, helps to create the airy intimacy of A Mother and Child with its Head in her Lap, where open doors on the left disclose a sunny exterior and open curtains on the right a pillowed bed—a stereoscope of housed comfort. (A Courtyard in Delft with a Woman and Child offers an even more distinctly double view, as if each eye is being offered a separate channel.) In his Amsterdam phase, the far doorway giving onto a sunny vista became a compulsive de Hooch signature; in one painting of the magnificent new town hall interior (The Interior of the Burgomasters’ Council Chamber in the Amsterdam Town Hall with Visitors, circa 1663-1665), he violated the actual design to create such a motif, and in another (A Couple Walking in the Citizens’ Hall of the Amsterdam Town Hall, circa 1663-1665) a nineteenth-century restorer did it for him, adding an imaginary room with checkerboard floor and bright window to make the painting, presumably, more de Hoochian. But the distinguished passage of this painting is the beautifully hovering patch of sunshine which, falling through an unseen window, splashes the base of a great pilaster and bounces—it or a brother beam—across the chests of the strolling couple.

Advertisement

Two Amsterdam paintings not in the show but reproduced in the catalog, Woman Lacing Her Bodice Beside a Cradle (circa 1661-1663) and A Boy Handing a Woman a Basker in a Doorway (circa 1660-1663), show his indoor-outdoor fugue to exquisite, enameled effect. Such canvases, though more dryly detailed than any by Vermeer, have been lifted above the anecdotal interest of genre scenes to a plane of pure painting—“pure” for lack of a juster word to denote painting as disinterested exploration and meditation. The splash of golden light adds almost nothing to the republican splendor of the town hall or the picturesque character of the couple; it adds a good deal to our sense of time and of the universe.

What a curious thing, after all, genre painting is, beginning with the name—an inexpressive term, the French word for “sort” or “type,” first used in English, according to the OED, in 1849 to designate paintings of ordinary life. Though examples can be found in French painting (Chardin) and American (Winslow Homer, the Ashcanners), the supreme examples belong to the Dutch seventeenth century. The emergent middle class holds up the mirror to itself in saucy eclipse of all those gods and kings who formerly held a monopoly on glorification. A school arises that abandons the religious and mythological subjects which have hitherto formed the nearly exclusive matter of European painting and substitutes, with a vengeance, the daily ordinary, including such ignoble scenes as soldiers getting drunk in a brothel and mothers wiping their infants’ befouled bottoms. Its genealogy can be traced from late-medieval calendar illustrations through the scenes of peasant life by Pieter Breughel the Elder; but a crucial transition, I think, exists in the biblical scenes by Caravaggio and Rembrandt and (a bit later) de La Tour that garbed the incidents of Holy Scripture in the particularized faces and intimate gestures of a neighborhood household.

These Bible people are people we know: a Protestant assertion that brings the sublime down to earth. Dutch genre painting, according to Mr. Sutton’s excellent, comprehensive catalog text, began in the sixteenth century with frankly cautionary illustrations of intemperance and brothel revelry. With gusto Jan Steen depicted The Effects of Intemperance (circa 1663- 1665), The Drunken Couple, The Disreputable Woman, The Disorderly Household. The debauches of the Prodigal Son and of Lot with his daughters came in for pointed illustration. Soldiers, a constant Dutch presence in these decades of the Eighty Years War, were a favorite topic for “guardroom” paintings that showed them as tipsy and lusty—no military gloire here.

De Hooch began with brownish, stilted, claustral depictions of “merry company”—rest and recreation it was called in later days. A sinister though increasingly vague atmosphere of sexual negotiation dominates. In A Merry Company with Two Men and Two Women (circa 1657-1658) the painter startles us with, near the center of the canvas, in a quartet of otherwise averted or cursory faces, a woman’s face, sunlit, of vivid expectancy and alertness. Her wrist is being clasped by the man across the table from her, so it is clear enough what she is being alert and expectant about; but here, in a room whose shape and lighting could be straight from Vermeer, de Hooch goes further than he has to and gives us a brilliant, dramatic exploration of a live person—a kind of painterly grace has descended on this hyperanimated woman of dubious virtue. Something of the same abrupt brilliance returns in a late painting of his Amsterdam period, A Man Reading a Letter to a Woman (circa 1670-1674). Her red dress and gold skirt attract the sun, but our attention is held by the complex expression on her listening face, patient yet skeptical. The genius of genre painting was that, unlike more hierarchical and stylized and reverent modes, it posed no deflecting alternative to reality.

Rather, it insisted on it—the mundane quotidian in its ambiguous, charged stillness. And, just as sunlight broke through the leaded windows into the whitewashed rooms, a freshly felt glory infused representation. The Dutch virtues—a fierce cleanness and orderliness in the face of threats from monarchal empires and the unruly sea—idealized the patient rounds of daily housekeeping. How central a sense of shelter was to the beauty of Dutch genre painting is indicated by the drab sunlessness of de Hooch’s outdoor paintings of women doing laundry or of families posing for a portrait: there was too much naked light for him; he could not form defining shadows or highlights. His Amsterdam pictures get darker and darker, framing a few spotlit figures. Circumambient light seen from inside, and experienced within; that is de Hooch’s settled manner, and a metaphor for Protestantism’s new version of religious experience.

This Issue

February 18, 1999