The writer’s first job is not to have opinions but to tell the truth…and refuse to be an accomplice of lies or misinformation. Literature is the expression of nuance and contrariness against the voices of simplification. The job of the writer is to make it harder to believe the mental despoilers. The job of the writer is to help make us see the world as it is, which is to say, full of many different claims and parts and experiences.

It is the job of the writer to depict the realities, the foul realities, the realities of rapture. It is the essence of the wisdom furnished by literature (the plurality of literary achievement) to help us to understand that, whatever is happening, something else is always going on. I am haunted by that “something else.”

I am haunted by the conflict of rights and of values I cherish. For instance that—sometimes—telling the truth does not further justice. That—sometimes—the furthering of justice may entail suppressing a good part of the truth.

Many of the twentieth century’s most notable writers, in their activity as public voices, were accomplices in the suppression of truth to further what they understood to be (what were, in many cases) just causes.

My own view is, if I have to choose between truth and justice—of course, I don’t want to choose—I choose truth.

Of course, I believe in righteous action. But is it the writer who is performing it? These are three different things: speaking, which I am doing now; writing, which gives me whatever claim I have to this incomparable prize; and being, being a person who believes in righteous action, and solidarity with others. As Roland Barthes once observed: “Who speaks is not who writes, and who writes is not who is.”

And of course I have opinions, political opinions, some of them formed from reading and discussing and reflecting, but not from firsthand experience. Let me share with you two opinions of mine—quite predictable opinions, in the light of public positions I’ve taken on matters about which I have some direct knowledge.

I believe that the doctrine of collective responsibility, as a rationale for collective punishment, is never justified, militarily or ethically. I mean the use of disproportionate firepower against civilians, the demolition of their homes and destruction of their orchards and groves, the deprivation of their livelihood and their access to employment, schooling, medical services, free access to neighboring towns and communities…all as a punishment for hostile military activity which may or may not even be in the vicinity of these civilians.

I also believe that there can be no peace here until the planting of Israeli communities in the Territories is halted, followed by the eventual dismantling of these settlements.

I wager that these two opinions of mine are shared by many people here in this hall. I suspect that, to use an old American expression, I’m preaching to the choir.

But do I hold these predictable opinions as a writer? Or do I not hold them as a person of conscience and then use my position as a writer to add my voice to others saying the same thing? The influence a writer can exert is purely adventitious. It is, now, an aspect of the culture of celebrity.

There is something vulgar about public dissemination of opinions on matters about which one does not have extensive firsthand knowledge. If I speak of what I do not know, or know hastily, this is mere opinion-mongering.

I say this as a matter of honor. The honor of literature. The project of having an individual voice. Serious writers, creators of literature, shouldn’t just express themselves differently from the way the mass media does. They should be in opposition to the communal drone of the newscast and the talk show.

If literature itself, the great enterprise that has been conducted (within our purview) for some two and a half millennia—if literature itself as such embodies a wisdom, and I think it does, and is indeed the root of the importance we give to literature—it is by demonstrating the multiplicity and contradictions of our private and communal destinies. It will remind us that there can be contradictions, sometimes irreducible conflicts, among the values we most cherish. (This is what is meant by “tragedy.”) Literature will remind us of the “also” and “the something else.”

The wisdom of literature is quite antithetical to having opinions. “Nothing is my last word about anything,” said Henry James. Furnishing opinions, even correct opinions—whenever asked—cheapens what novelists and poets do best, which is to sponsor reflectiveness, to perceive complexity.

Let the others, the celebrities and the politicians, talk down to us; lie. If being both a writer and a public voice could stand for anything better, it would be that writers would consider the formulation of opinions and judgments to be a grave responsibility.

Advertisement

Another problem with opinions. They are agencies of self-immobilization. What writers do should free us up, shake us up. Open avenues of compassion and new interests. Remind us that we might, just might, aspire to become different, and better, than we are. Remind us that we can change.

As Cardinal Newman said, “In a higher world it is otherwise, but here below to live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.”

I am grateful to have been awarded the Jerusalem Prize. I accept it as an honor to all those committed to the enterprise of literature. I accept it in homage to all the writers and readers in Israel and in Palestine struggling to create literature made of singular voices and the multiplicity of truths. I accept the prize in the name of peace and the reconciliation of injured and fearful communities. Necessary peace. Necessary concessions and new arrangements. Necessary abatement of stereotypes. Necessary persistence of dialogue. I accept the prize—this international prize, sponsored by an international book fair—as an event that honors, above all, the international republic of letters.

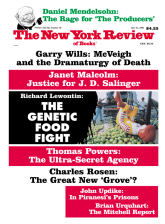

This Issue

June 21, 2001