The February 2000 issue of the Bucharest men’s magazine Plai cu Boi features one Princess Brianna Caradja. Variously clad in leather or nothing much at all, she is spread across the center pages in a cluster of soft-focus poses, abusing subservient half-naked (male) serfs. The smock-clad underlings chop wood, haul sleighs, and strain against a rusting steam tractor, chained to their tasks, while Princess Brianna (the real thing, apparently) leans lasciviously into her furs, whip in hand, glaring contemptuously at men and camera alike, in a rural setting reminiscent of Woody Allen’s Love and Death.

An acquired taste, perhaps. But then Mircea Dinescu, editor of Plai cu Boi and a well-known writer and critic, is no Hugh Hefner. His centerfold spread has a knowing, sardonic undertone: it plays mockingly off Romanian nationalism’s obsession with peasants, land, and foreign exploitation. Princess Brianna is a fantastical, camp evocation of aristocratic hauteur and indulgence, Venus in Furs for a nation that has suffered serial historical humiliation. The ironic juxtaposition of pleasure, cruelty, and a rusting tractor adds a distinctive local flourish. You wouldn’t find this on a newsstand elsewhere in Europe. Not in Prague, much less Vienna. You wouldn’t even find it in Warsaw. Romania is different.1

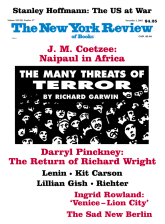

In December 2000, Romanians went to the polls. In a nightmare of post-Communist political meltdown, they faced a choice for president between Ion Iliescu, a former Communist apparatchik, and Corneliu Vadim Tudor, a fanatical nationalist. All the other candidates had been eliminated in a preliminary round of voting. The parties of the center, who had governed in uneasy coalition since 1996, had collapsed in a welter of incompetence, corruption, and recrimination (their leader, the former university rector Emil Constantinescu, did not even bother to stand for a second presidential term). Romanians elected Iliescu by a margin of two-to-one; that is, one in three of those who voted preferred Tudor. Tudor’s platform combines irredentist nostalgia with attacks on the Hungarian minority—some 2 million people out of a population of 22 million—and openly espouses anti-Semitism. The magazines that support him carry cartoons with slanderous and scatological depictions of Hungarians, Jews, and gypsies. They would be banned in some Western democracies.2

Both Tudor and Iliescu have deep roots in pre-1989 Romanian politics. Tudor was Nicolae Ceausescu’s best- known literary sycophant, writing odes to his leader’s glory before making the easy switch from national communism to ultranationalism and founding his Greater Romania Party in 1991 with émigré cash. Ion Iliescu is one of a number of senior Communists who turned against Ceausescu and manipulated a suspiciously stage-managed revolution to their own advantage. President of Romania between 1990 and 1996 before winning again in 2000, he is popular throughout the countryside, especially in his native region of Moldavia, where his picture is everywhere. Even urban liberals voted for him, holding their noses (and with Tudor as the alternative). There are men like these in every East European country, but only in Romania have they done so well. Why?

By every measure, Romania is at the bottom of the European heap. The Romanian economy, defined by per capita gross domestic product, ranked eighty-seventh in the world in 1998, below Namibia and just above Paraguay (Hungary ranked fifty-eighth). Life expectancy is lower in Romania than anywhere else in Central or Southeastern Europe: for men it is just sixty-six years, less than it was in 1989 and ten years short of the EU average. It is estimated that two out of five Romanians live on less than $30 per month (contrast, e.g., Peru, where the minimum monthly wage today is $40). By all conventional measures, Romania is now best compared to regions of the former Soviet Union (except the Baltics, which are well ahead) and has even been overtaken by Bulgaria. According to The Economist’s survey for the year 2000, the “quality of life” in Romania ranks somewhere between Libya and Lebanon. The European Union has tacitly acknowledged as much: the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament lists Romania as last among the EU-candidate countries, and slipping fast.3

It wasn’t always thus. It is not just that Romania once had a flourishing oil industry and a rich and diverse agriculture. It was a country with cosmopolitan aspirations. Even today the visitor to Bucharest can catch glimpses of a better past. Between the 1870s and the First World War the city more than doubled in size, and some of the great boulevards laid down then and between the wars, notably the Calea Victoria at its very center, once stood comparison with the French originals on which they were modeled. Bucharest’s much-advertised claim to be “the Paris of the East” was not wholly spurious. Romania’s capital had oil-fired street lamps before Vienna and got its first electric street lighting in 1882, well before many Western European cities. In the capital and in certain provincial towns—Iasåüi, Timisåüoara—the dilapidated charm of older residences and the public parks has survived the depredations of communism, albeit barely.4

Advertisement

One could speak in a comparable vein of Prague or Budapest. But the Czech Republic and Hungary, like Poland, Slovenia, and the Baltic lands, are recovering unexpectedly well from a century of war, occupation, and dictatorship. Why is Romania different? One’s first thought is that it isn’t different; it is the same—only much worse. Every post-Communist society saw deep divisions and resentments; only in Romania did this lead to serious violence. First in the uprising against Ceausescu, in which hundreds died; then in interethnic street-fighting in Târgu-Muresåü in March 1990, where eight people were killed and some three hundred wounded in orchestrated attacks on the local Hungarian minority. Later in Bucharest, in June 1990, miners from the Jiu Valley pits were bussed in by President Ion Iliescu (the same) to beat up student protesters: there were twenty-one deaths and 650 people were injured.

In every post-Communist society some of the old nomenklatura maneuvered themselves back into positions of influence. In Romania they made the transition much more fluently than elsewhere. As a former Central Committee secretary, Iliescu oversaw the removal of the Ceausescus (whose trial and execution on Christmas Day 1989 were not shown on television until three months later); he formed a “National Salvation Front” that took power under his own direction; he re-cycled himself as a “good” Communist (to contrast with the “bad” Ceausescu); and he encouraged collective inattention to recent history. By comparison with Poland, Hungary, or Russia there has been little public investigation of the Communist past—efforts to set up a Romanian “Gauck Commission” (modeled on the German examination of the Stasi archives) to look into the activities of the Securitate have run up against interference and opposition from the highest levels of government.

Transforming a dysfunctional state-run economy into something resembling normal human exchange has proven complicated everywhere. In Romania it was made harder. Whereas other late-era Communist rulers tried to buy off their subjects with consumer goods obtained through foreign loans, under Ceausescu the “shock therapy” advocated after 1989 in Poland and elsewhere had already been applied for a decade, for perverse ends. Romanians were so poor they had no belts left to tighten; and they could hardly be tempted by the reward of long-term improvement. Instead, like Albania and Russia, Romania fell prey to instant market gratification in the form of pyramid schemes, promising huge short-term gains without risk. At its peak one such operation, the “Caritas” scam which ran from April 1992 to August 1994, had perhaps four million participants—nearly one in five of the population. Like “legitimate” privatization, these pyramid schemes mostly functioned to channel private cash into mafias based in old Party networks and the former security services.

Communism was an ecological disaster everywhere, but in Romania its mess has proven harder to clean up. In the industrial towns of Transylvania—in places like Hunedoara or Baia Mare, where a recent leak from the Aural gold mine into the Tisza River poisoned part of the mid-Danubian ecosystem—you can taste the poison in the air you breathe, as I found on a recent visit there. The environmental catastrophe is probably comparable in degree to parts of eastern Germany or northern Bohemia, but its extent is greater: whole tracts of the country are infested with bloated, rusting steel mills, abandoned petrochemical refineries, and decaying cement works. Privatization of uneconomic state enterprises is made much harder in Romania in part because the old Communist rulers have succeeded in selling the best businesses to themselves, but also because the cost of cleaning up polluted water and contaminated soil is prohibitive and off-putting to the few foreign companies who express an initial interest.

The end of communism has brought with it nearly everywhere a beginning of memory. In most places this started with the compensatory glorification of a pre-Communist age but gave way in time to more thoughtful discussion of politically sensitive topics from the national past, subjects on which Communists were typically as silent as nationalists. Of these the most painful has been the experience of World War II and local collaboration with the Germans—notably in their project to exterminate the Jews. Open debate on such matters has come furthest in Poland; in Romania it has hardly begun.

Romania was formally neutral in the early stages of World War II; but under the military dictator Marshal Ion Antonescu the country aligned itself with Hitler in November 1940 and joined enthusiastically in the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, contributing and losing more troops than any of Germany’s other European allies. In May 1946, with Romania firmly under Soviet tutelage, Antonescu was tried and executed as a war criminal. He has now been resurrected in some circles in post-Communist Romania as a national hero: statues have been erected and memorial plaques inaugurated in his honor. Many people feel uneasy about this, but few pay much attention to what would, almost anywhere else, be Antonescu’s most embarrassing claim to fame: his contribution to the Final Solution of the Jewish Question.5

Advertisement

The conventional Romanian position has long been that, whatever his other sins, Antonescu saved Romania’s Jews. And it is true that of the 441,000 Jews listed in the April 1942 census, the overwhelming majority survived, thanks to Antonescu’s belated realization that Hitler would lose the war and his consequent rescinding of plans to deport them to extermination camps. But that does not include the hundreds of thousands of Jews living in Bessarabia and Bukovina, Romanian territories humiliatingly ceded to Stalin in June 1940 and triumphantly reoccupied by Romanian (and German) troops after June 22, 1941. Here the Romanians collaborated with the Germans and outdid them in deporting, torturing, and murdering all Jews under their control. It was Romanian soldiers who burned alive 19,000 Jews in Odessa, in October 1941; who shot a further 16,000 in ditches at nearby Dalnick; and who so sadistically mistreated Jews being transported east across the Dniester River that even the Germans complained.6

By the end of the war the Romanian state had killed or deported over half the total Jewish population under its jurisdiction. This was deliberate policy. In March 1943 Antonescu declared: “The operation should be continued. However difficult this might be under present circumstances, we have to achieve total Romanianization. We will have to complete this by the time the war ends.” It was Antonescu who permitted the pogrom in Iasåüi (the capital of Moldavia, in the country’s north-east) on June 29 and 30, 1941, where at least seven thousand Jews were murdered. It was Antonescu who ordered in July 1941 that fifty “Jewish Communists” be exterminated for every Romanian soldier killed by partisans. And it was unoccupied Romania that alone matched the Nazis step for step in the Final Solution, from legal definitions through extortion and deportation to mass extermination.7

If Romania has hardly begun to think about its role in the Holocaust, this is not just because the country is a few years behind the rest of Europe in confronting the past. It is also because it really is a little bit different. The project to get rid of the Jews was intimately tied to the longstanding urge to “Romanianize” the country in a way that was not true of anti-Semitism anywhere else in the region. For many Romanians the Jews were the key to the country’s all-consuming identity problem, for which history and geography were equally to blame.

2.

Peasants speaking Romanian have lived in and around the territories of present-day Romania for many centuries. But the Romanian state is comparatively new. Romanians were for many centuries ruled variously by the three great empires of Eastern Europe: the Russian, the Austro-Hungarian, and the Ottoman. The Turks exercised suzerainty over Wallachia (where Bucharest sits) and Moldavia to its northeast. The Hungarians and latterly the Habsburgs ruled Transylvania to the northwest and acquired the neighboring Bukovina (hitherto in Moldavia) from the Turks in 1775.

The Russians for their part pressed the declining Ottoman rulers to turn over to them effective control of this strategic region. In 1812, at the Treaty of Bucharest, Tsar Alexander I compelled Sultan Mahmud II to cede Bessarabia, then part of eastern Moldavia. “Romania” at this point was not yet even a geographical expression. But in 1859, taking advantage of continuing Turkish decline and Russia’s recent defeat in the Crimean War, Moldavia and Wallachia came together to form the United Principalities (renamed Romania in 1861), although it was not until 1878, following a Turkish defeat at Russian hands, that the country declared full inde-pendence, and only in 1881 was its existence recognized by the Great Powers.

From then until the Treaty of Versailles, the Romanian Old Kingdom, or Regat, was thus confined to Wallachia and Moldavia. But following the defeat of all three East European empires in World War I, Romania in 1920 acquired Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Transylvania, as well as part of northern Bulgaria. As a result the country grew from 138,000 square kilome-ters to 295,000 square kilometers, and doubled its population. The dream of Greater Romania—“from the Dniester to the Tisza” (i.e., from Russia to Hungary) in the words of its national poet Mihai Eminescu—had been fulfilled.

Romania had become one of the larger countries of the region. But the Versailles treaties, in granting the nationalists their dream, had also bequeathed them vengeful irredentist neighbors on all sides and a large minority population (grown overnight from 8 to 27 percent) of Hungarians, Germans, Ukrainians, Russians, Serbs, Greeks, Bulgarians, Gypsies, and Jews—some of whom had been torn from their homelands by frontier changes, others who had no other home to go to. Like the newly formed Yugoslavia, Romania was at least as ethnically mixed as any of the preceding empires. But Romanian nationalist leaders insisted on defining it as an ethnically homogeneous nation-state. Resident non-Romanians—two people out of seven—were “foreigners.”

The result has been a characteristically Romanian obsession with identity.8 Because so many of the minorities lived in towns and pursued commerce or the professions, nationalists associated Romanian-ness with the peasantry. Because there was a close relationship between language, ethnicity, and religion among each of the minorities (Yiddish-speaking Jews, Catholic and Lutheran Hungarians, Lutheran Germans, etc.), nationalists insisted upon the (Orthodox) Christian quality of true Romanian-ness. And because Greater Romania’s most prized acquisition, Transylvania, had long been settled by Hungarians and Romanians alike, nationalists (and not only they) made great play with the ancient “Dacian” origins.9

Today the Jewish “question” has been largely resolved—there were about 760,000 Jews in Greater Romania in 1930; today only a few thousand are left.10 The German minority was sold to West Germany by Ceausescu for between 4,000 and 10,000 deutschmarks per person, depending on age and qualification; between 1967 and 1989 200,000 ethnic Germans left Romania this way. Only the two million Hungarians (the largest official minority in Europe) and an uncounted number of Gypsies remain.11 But the bitter legacies of “Greater Romania” between the World Wars stubbornly persist.

In a recent contribution to Le Monde, revealingly titled “Europe: la plus-value roumaine,” the current prime minister, Adrian Nastase, makes much of all the famous Romanians who have contributed to European and especially French culture over the years: Eugène Ionescu, Tristan Tzara, E.M. Cioran, Mircea Eliade…12 But Cioran and, especially, Eliade were prominent intellectual representatives of the Romanian far right in the 1930s, active supporters of Corneliu Zelea Codreanu’s Iron Guard. Eliade at least, in his mendaciously selective memoirs, never even hinted at any regrets. This would hardly seem a propitious moment to invoke him as part of Romania’s claim to international respect.

Nastase is not defending Eliade. He is just trying, clumsily, to remind his Western readers how very European Romania really is. But it is revealing that he feels no hesitation in enlisting Eliade in his cause. Eliade, like the Jewish diarist Mihail Sebastian, was an admirer and follower of Nae Ionescu, the most influential of the many interwar thinkers who were drawn to the revivalist mysticism of Romania’s fascists.13 It was Ionescu, in March 1935, who neatly encapsulated contemporary Romanian cultural paranoia: “A nation is defined by the friend-foe equation.” Another follower was Constantin Noica, a reclusive thinker who survived in Romania well into the Ceausescu era and has admirers among contemporary Romania’s best-known scholars and writers. Noica, too, suppressed evidence of his membership in the Iron Guard during the Thirties.14

This legacy of dissimulation has left many educated Romanians more than a little unclear about the propriety of their cultural heritage: If Eliade is a European cultural icon, what can be so wrong with his views on the un-Christian threat to a harmonious national community? In March 2001 I spoke about “Europe” in Iasåüi to a cultivated audience of students, professors, and writers. One elderly gentleman, who asked if he might put his question in Italian (the discussion was taking place in English and French), wondered whether I didn’t agree that the only future for Europe was for it to be confined to “persons who believe in Jesus Christ.” It is not, I think, a question one would get in most other parts of Europe today.

3.

The experience of communism did not change the Romanian problem so much as it compounded it. Just as Romanian politicians and intellectuals were insecure and paranoid and resentful about their country’s place in the scheme of things—sure that the Jews or the Hungarians or the Russians were its sworn enemies and out to destroy it—so the Romanian Communist Party was insecure and paranoid, even by the standards of Communist parties throughout Eastern Europe.

In this case it was the Communists themselves who were overwhelmingly Hungarian or Russian or/and Jewish.15 It was not until 1944 that the Party got an ethnic Romanian leader, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej—and one of the compensatory strategies of the Romanian Communists once installed in power was to wrap themselves in the mantle of nationalism. Dej began this in the late Fifties by taking his distance from the Soviets in the name of Romanian interests, and Ceausescu, who succeeded him in 1965, merely went further still.16

This led to an outcome for which the West must take some responsibility. Communism in Romania, even more under Dej than Ceausescu, was vicious and repressive—the prisons at Pitesåüti and Sighet, the penal colonies in the Danube delta, and the forced labor on the Danube–Black Sea Canal were worse than anything seen in Poland or even Czechoslovakia, for example.[17 ]But far from condemning the Romanian dictators, Western governments gave them every encouragement, seeing in Bucharest’s anti-Russian autocrats the germs of a new Tito.

Richard Nixon became the first US president to visit a Communist state when he came to Bucharest in August 1969. Charmed by Nicolae Ceausescu during a visit to Romania in 1978, Senator George McGovern praised him as “among the world’s leading proponents of arms control”; the British government invited the Ceausescus on a state visit in the same year; and as late as September 1983, when the awful truth about Ceausescu’s regime was already widely known, Vice President George Bush described him as “one of Europe’s good Communists.”18

National communism (“He may be a Commie but he’s our Commie”) paid off for Ceausescu and not just because he hobnobbed with Richard Nixon and the Queen of England. Romania was the first Warsaw Pact state to enter GATT (in 1971), the World Bank and the IMF (1972), to get European Community trading preferences (1973) and US Most-Favored-Nation status (1975). Western approval undercut Romanian domestic opposition, such as it was. No US president demanded that Ceausescu “let Romania be Romania.”

Even if a Romanian Solidarity movement had arisen, it is unlikely that it would have received any Western support. Because the Romanian leader was happy to criticize the Russians and send his gymnasts to the Los Angeles Olympics, the Americans and others said nothing about his domestic crimes (at least until the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev, after which the West had no use for an anti-Soviet maverick dictator). Indeed, when in the early Eighties Ceausescu decided to pay down Romania’s huge foreign debts by squeezing domestic consumption, the IMF could not praise him enough.

The Romanians, however, paid a terrible price for Ceausescu’s freedom of maneuver. To increase the population—a traditional Romanianist obsession—in 1966 he prohibited abortion for women under forty with fewer than four children (in 1986 the age barrier was raised to forty-five). In 1984 the minimum marriage age for women was reduced to fifteen. Compulsory monthly medical examinations for all women of childbearing age were introduced to prevent abortions, which were permitted, if at all, only in the presence of a Party representative.19 Doctors in districts with a declining birth rate had their salaries cut.

The population did not increase, but the death rate from abortions far exceeded that of any other European country: as the only available form of birth control, illegal abortions were widely performed, often under the most appalling and dangerous conditions. In twenty-three years the 1966 law resulted in the death of at least ten thousand women. The real infant mortality rate was so high that after 1985 births were not officially recorded until a child had survived to its fourth week—the apotheosis of Communist control of knowledge. By the time Ceausescu was overthrown the death rate of new-born babies was twenty-five per thousand and there were upward of 100,000 institutionalized children—a figure that has remained steady to the present. In the eastern department of Constanta, abandoned, malnourished, diseased children absorb 25 percent of the budget today.20

The setting for this national tragedy was an economy that was deliberately turned backward into destitution. To pay off Western creditors, Ceausescu obliged his subjects to export every available domestically produced commodity. Romanians were forced to use 40-watt bulbs at home so that energy could be exported to Italy and Germany. Meat, sugar, flour, butter, eggs, and much more were rationed. Fixed quotas were introduced for obligatory public labor on Sundays and holidays (the corvée, as it was known in ancien régime France). Gasoline usage was cut to the minimum and a program of horse-breeding to substitute for motorized vehicles was introduced in 1986.

Traveling in Moldavia or in rural Transylvania today, fifteen years later, one sees the consequences: horse-drawn carts are the main means of transport and the harvest is brought in by scythe and sickle. All socialist systems depended upon the centralized control of systemically induced shortages. In Romania an economy based on overinvestment in unwanted industrial hardware switched overnight into one based on preindustrial agrarian subsistence. The return journey will be long.

Nicolae Ceausescu’s economic policies had a certain vicious logic—Romania, after all, did pay off its international creditors—and were not without mild local precedent from pre-Communist times. But his urbanization projects were simply criminal. The proposed “systematization” of half of Romania’s 13,000 villages (disproportionately selected from minority communities) into 558 agro-towns would have destroyed what remained of the country’s social fabric. His actual destruction of a section of Bucharest the size of Venice ruined the face of the city. Forty thousand buildings were razed to make space for the “House of the People” and the five-kilometer-long, 150-meter-wide Victory of Socialism Boulevard. The former, designed as Ceausescu’s personal palace by a twenty-five-year-old architect, Anca Petrescu, is beyond kitsch. Fronted by a formless, hemicycle space that can hold half a million people, the building is so big (its reception area is the size of a soccer field), so ugly, so heavy and cruel and tasteless, that its only possible value is metaphorical.

Here at least it is of some interest, a grotesque Romanian contribution to totalitarian urbanism—a genre in which Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, Trujillo, Kim Il Sung, and now Ceausescu have all excelled.21 The style is neither native nor foreign—in any case, it is all façade. Behind the gleaming white frontages of the Victory of Socialism Boulevard there is the usual dirty gray, pre-cast concrete, just as a few hundred yards away there are the pitiful apartment blocks and potholed streets. But the façade is aggressively, humiliatingly, unrelentingly uniform, a reminder that totalitarianism is always about sameness; which is perhaps why it had a special appeal to a monomaniacal dictator in a land where sameness and “harmony”—and the contrast with “foreign” difference—were a longstanding political preoccupation.

Where, then, does Romania fit in the European scheme of things? It is not Central European in the geographical sense (Bucharest is closer to Istanbul than it is to any Central European capital). Nor is it part of Milan Kundera’s “Central Europe”: former Habsburg territories (Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Galicia)—a “kidnapped West”—subsumed into the Soviet imperium. The traveler in Transylvania even today can tell himself that he is in Central Europe—domestic and religious architecture, the presence of linguistic minorities, even a certain (highly relative) prosperity all evoke the region of which it was once a part. But south and east of the Carpathian Mountains it is another story. Except in former imperial cities like Timisåüoara, at the country’s western edge, even the idea of “Central Europe” lacks appeal for Romanians.22

If educated Romanians from the Old Kingdom looked west, it was to France. As Rosa Waldeck observed in 1942, “The Romanian horizon had always been filled with France; there had been no place in it for anyone else, even England.”23 The Romanian language is Latinate; the administration was modeled on that of Napoleon; even the Romanian fascists took their cue from France, with an emphasis on unsullied peasants, ethnic harmony, and an instrumentalized Christianity that echoes Charles Maurras and the Action Française.

The identification with Paris was genuine—Mihail Sebastian’s horror at the news of France’s defeat in 1940 was widely shared. But it was also a palpable overcompensation for Romania’s situation on Europe’s outer circumference, what the Romanian scholar Sorin Antohi calls “geocultural Bovaryism”—a disposition to leapfrog into some better place. The deepest Romanian fear seems to be that the country could so easily fall right off the edge into another continent altogether, if it hasn’t already done so. E.M. Cioran in 1972, looking back at Romania’s grim history, captured the point: “What depressed me most was a map of the Ottoman Empire. Looking at it, I understood our past and everything else.”

An open letter to Ceausescu from a group of dissident senior Communists in March 1989 reveals comparable anxieties: “Romania is and remains a European country…. You have begun to change the geography of the rural areas, but you cannot move Romania into Africa.” In the same year the playwright Eugène Ionescu described the country of his birth as “about to leave Europe for good, which means leaving history.”24

The Ottoman Empire is gone—it was not perhaps such a bad thing and anyway left less direct an imprint on Romania than it did elsewhere in the Balkans. But the country’s future remains cloudy and, as always, humiliatingly dependent upon the kindness of strangers. About the only traditional international initiative Romania could undertake would be to seek the return of Bessarabia (since 1991 the independent state of Moldova), and today only C.V. Tudor is demanding it.25 Otherwise politically active people in Bucharest have staked everything on the European Union. Romania first applied to join in 1995 and was rejected two years later (a humiliation which, together with a cold shoulder from NATO, probably sealed the fate of the center-right government). In December 1999 the EU at last invited Romania (along with Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Malta, and Turkey) to begin negotiations to join.

Romania will be a hard pill for Brussels to swallow, and most Eurocrats privately hope it won’t join for a long time. The difficulties faced by the German Federal Republic in absorbing the former GDR would be dwarfed by the cost to the EU of accommodating and modernizing a country of 22 million people starting from a far worse condition. Romanian membership in the EU would bring little but headaches. Western investors will surely continue to look to Budapest, Warsaw, or Prague, especially once these are firmly within the EU. Who will pour money into Bucharest? Today, only Italy has significant trade with Romania; the Germans have much less, and the French—oh irony!—trail far behind.

Romania today, Mr. Nastase’s best efforts notwithstanding, brings little to Europe. Unlike Budapest or Prague, Bucharest is not part of some once-integrated Central Europe torn asunder by history; unlike Warsaw or Lju-bljana, it is not an outpost of Catholic Europe. Romania is peripheral and the rest of Europe stands to gain little from its presence in the union. Left outside it would be an embarrassment, but hardly a threat. But for just this reason Romania is the EU’s true test case.

Hitherto, membership in the EEC/ EC/EU has been extended to countries already perceived as fully European. In the case of Finland or Austria, membership in the union was merely confirmation of their natural place. The same will be true of Hungary and Slovenia. But if the European Union wishes to go further, to help make “European” countries that are not—and this is implicit in its international agenda and its criteria for membership—then it must address the hard cases.

Romania is perhaps the hardest: a place that can only overcome its past by becoming “European,” which means joining the European Union as soon as possible. But Romania has scant prospect of meeting EU criteria for membership in advance of joining. Thus Brussels would need to set aside its present insistence that applicant countries conform to “European” norms before being invited into the club. But there is no alternative in Romania’s case. Romanian membership will cost West Europeans a lot of money; it will do nothing for the euro; it will expose the union to all the ills of far-eastern Europe. In short, it would be an act of apparent collective altruism, or at least unusually enlightened self-interest.

But without such a willingness to extend its benefits to those who actually need them, the union is a mockery—of itself and of those who place such faith in it. Already the mere prospect of joining, however dim, has improved the situation of the Hungarian minority in Transylvania and has strengthened the hand of reformers—without pressure from Brussels, the government in Bucharest would never, for example, have overcome Orthodox Church objections last year and reformed the humiliating laws against homosexuality. As in the past, international leverage has prompted Romanian good behavior.26 And as in the past, international disappointment would almost certainly carry a price at home.

In 1934 the English historian of Southeastern Europe R.W. Seton-Watson wrote, “Two generations of peace and clean government might make of Roumania an earthly paradise.”27 That is perhaps a lot to ask (though it shows how far the country has fallen). But Romania needs a break. The fear of being “shipwrecked at the periphery of history in a Balkanized democracy” (as Eliade put it) is real, however perverse the directions that fear has taken in the past.

“Some countries,” according to E.M. Cioran, looking back across Romania’s twentieth century, “are blessed with a sort of grace: everything works for them, even their misfortunes and their catastrophes. There are others for whom nothing succeeds and whose very triumphs are but failures. When they try to assert themselves and take a step forward, some external fate intervenes to break their momentum and return them to their starting point.”28

The last Romanian elections, with a third of the vote going to Tudor, were a warning shot. What keeps Ion Iliescu and his prime minister out of the hands of their erstwhile nationalist allies is the promise of Europe. If Romania is not to fall back into a slough of resentful despond, or worse, that promise must be fulfilled.

This Issue

November 1, 2001

-

1

I am deeply grateful to Professor Mircea Mihâies for bringing Plai cu Boi to my attention.

↩ -

2

For an excellent discussion of Tudor’s politics and a selection of cartoons from Politica and România Mare, see Iris Urban, “Le Parti de la Grande Roumanie, doctrine et rapport au passé: le nationalisme dans la transition post-communiste,” in Cahiers d’études, No. 1 (2001) (Bucharest: Institut Roumain d’Histoire Récente). See also Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, “The Return of Populism—The 2000 Romanian Elections,” in Government and Opposition, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Spring 2001), pp. 230–252.

↩ -

3

For data see The Economist, World in Figures, 2001 edition.

↩ -

4

For an evocative account of life in interwar Bukovina after its reunion with Moldavia in 1920, see Gregor von Rezzori, The Snows of Yesteryear (Vintage, 1989).

↩ -

5

The infamous prison at Sighet, in the Maramuresåü region on Romania’s northern border with Ukraine, has been transformed into a memorial and museum. There is full coverage of the suffering of Communist Romania’s many political prisoners, rather less reference to Sighet’s even more notorious role as a holding pen for Transylvanian Jews on their way to Auschwitz. This was not the work of Romanians—the region had been returned to Hungary by Hitler in August 1940—but the silence is eloquent.

↩ -

6

“The behavior of certain representatives of the Rumanian army, which have been indicated in the report, will diminish the respect of both the Rumanian and German armies in the eyes of public [sic] here and all over the world.” Chief of Staff, XI German Army, July 14, 1941, quoted in Matatias Carp, Holocaust in Romania: Facts and Documents on the Annihilation of Romania’s Jews, 1940–1944 (Bucharest: Atelierele Grafice, 1946; reprinted by Simon Publications, 2000), p. 23, note 8. There is a moving account of the deportation of the Jews of Bukovina and Bessarabia, the pogrom in Iasåüi, and the behavior of Romanian soldiers in Curzio Malaparte, Kaputt (Northwestern University Press, 1999; first published 1946).

↩ -

7

See Carp, Holocaust in Romania, p. 42, note 34, and pp. 108–109. Radu Ioanid accepts the figure of 13,266 victims of the Iasåüi pogrom, based on contemporary estimates. See his careful and informative The Holocaust in Romania: The Destruction of Jews and Gypsies Under the Antonescu Regime, 1940–1944 (Ivan R. Dee, 2000), p. 86.

↩ -

8

See Irina Livezeanu, Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building and Ethnic Struggle, 1918–1930 (Cornell University Press, 1995), an important book.

↩ -

9

The reference is to the Imperial Roman province of Dacia. Romanian antiquarians claim that Dacian tribes survived the Roman occupation and maintained unbroken settlement in Transylvania; Hungarians insist that when the Magyars arrived from the east in the tenth century the place was essentially empty, with Romanians coming later. For what it is worth, both sides are probably in error. Meanwhile the Dacia motorworks still manufactures a Romanian car—the Dacia 1300—familiar to middle-aged Frenchmen as the Renault 12 (first appearance: 1969). The Hungarians have nothing remotely so ancient with which to compete.

↩ -

10

Whatever the Jewish “problem” was about, it had little to do with real or imagined Jewish economic power. The accession of Bessarabia and Bukovina in 1920 added hundreds of thousands of Jews to Romania’s population. Most of them were poor. The Bessarabian-born writer Paul Goma describes his father’s response to the fascists’ cry of “Down with the Jews!”: “But how much further down could our little Jew get than the village shopkeeper?” See Paul Goma, My Childhood at the Gate of Unrest (Readers International, 1990), p. 64. Nevertheless, according to Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, founder in 1927 of the League of the Archangel Michael (later the Iron Guard), “The historic mission of our generation is the solution of the Jewish problem.” Codreanu is quoted by Leon Volovici in Nationalist Ideology and AntiSemitism: The Case of Romanian Intellectuals in the 1930s (Pergamon, 1991), p. 63. Codreanu was homicidal and more than a little mad. But his views were widely shared.

↩ -

11

Just this year the Hungarian government passed a status law giving certain national rights and privileges to Hungarians living beyond the state’s borders. This has understandably aroused Romanian ire at what some see as renewed irredentist ambition in Budapest; from the point of view of the Hungarians of Transylvania, however, the new law simply offers them some guarantees of protection and a right to maintain their distinctive identity. For a sharp dissection of identity debates and their political instrumentalization after communism, see Vladimir Tismaneanu, Fantasies of Salvation: Democracy, Nationalism, and Myth in Post-Communist Europe (Princeton University Press, 1998), notably Chapter 3, “Vindictive and Messianic Mythologies,” pp. 65–88.

↩ -

12

Adrian Nastase, “Europe: la plus-value roumaine,” Le Monde, July 23, 2001.

↩ -

13

On Sebastian, Eliade, and the anti-Semitic obsessions of Bucharest’s interwar literati, see Peter Gay’s review of Sebastian’s Journal, 1935–1944: The Fascist Years (Ivan R. Dee, 2000) in The New York Review, October 4, 2001. For a representative instance of Eliade’s views on Jews, see for example Sebastian’s diary entry for September 20, 1939, where he recounts a conversation with Eliade in which the latter is as obsessed as ever with the risk of “a Romania again invaded by kikes” (p. 238). Sebastian’s diary should be read alongside that of another Bucharest Jew, Emil Dorian: The Quality of Witness: A Romanian Diary, 1937–1944 (Jewish Publication Society of America, 1982).

↩ -

14

On Noica see Katherine Verdery, National Ideology Under Socialism: Identity and Cultural Politics in Ceausescu’s Romania (University of California Press, 1991), Chapter 7, “The ‘School’ of Constantin Noica.” Ionescu is quoted by Sebastian, Journal, p. 9.

↩ -

15

Among the most important leaders of the Romanian Party, first in exile in Moscow and then in Bucharest, until she was purged in 1952 was Ana Pauker, daughter of a Moldavian rabbi. See Robert Levy, Ana Pauker: The Rise and Fall of a Jewish Communist (University of California Press, 2000).

↩ -

16

See the comprehensive analysis by Vladimir Tismaneanu, “The Tragicomedy of Romanian Communism,” in Eastern European Politics and Societies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Spring 1989), pp. 329–376. Khrushchev, who had little time for Romanians, sought to confine them to an agricultural role in the international Communist distribution of labor; Dej and Ceausescu preferred to secure national independence via a neo-Stalinist industrialization drive.

↩ -

18

For the American story, see Joseph F. Harrington and Bruce J. Courtney, Tweaking the Nose of the Russians: Fifty Years of American–Romanian Relations, 1940–1950 (East European Monographs/Columbia University Press, 1991). Even The Economist, in August 1966, called Ceausescu “the De Gaulle of Eastern Europe.” As for De Gaulle himself, on a visit to Bucharest in May 1968 he observed that while Ceausescu’s communism would not be appropriate for the West, it was probably well suited to Romania: “Chez vous un tel régime est utile, car il fait marcher les gens et fait avancer les choses.” (“For you such a regime is useful, it gets people moving and gets things done.”) President François Mitterrand, to his credit, canceled a visit to Romania in 1982 when his secret service informed him of Romanian plans to murder Paul Goma and Virgil Tanase, Romanian exiles in Paris.

↩ -

19

“The foetus is the socialist property of the whole society” (Nicolae Ceausescu). See Katherine Verdery, What Was Socialism and What Comes Next? (Princeton University Press, 1996); Ceausescu is quoted on p. 65.

↩ -

20

Even today, Romania’s abortion rate is 1,107 abortions per 1,000 live births. In the EU the rate is 193 per thousand, in the US 387 per thousand.

↩ -

21

And Le Corbusier.

↩ -

22

From a Transylvanian perspective, Bucharest is a “Balkan,” even “Byzantine,” city. I am deeply grateful to Professor Mircea Mihaies, Adriana Babeti, and the “Third Europe” group at the University of Timisåüoara for the opportunity of an extended discussion on these themes in October 1998. Our conversation was transcribed and published last year, with a generous introduction by Professor Vladimir Tismaneanu, as Europa Iluziilor (Iasåüi: Editura Polirom, 2000), notably pp. 15–131.

↩ -

23

R.G. Waldeck, Athene Palace (Robert McBride, 1942; reprinted by the Center for Romanian Studies, Iasåüi, 1998). The quote is from the reprint edition, p. 10.

↩ -

24

For Cioran see E.M. Cioran, Oeuvres (Paris: Gallimard, 1995), p. 1779: “Ce qui m’a le plus déprimé, c’est une carte de l’Empire ottoman. C’est en la regardant que j’ai compris notre passé et le reste.” The letter to Ceausescu is cited by Kathleen Verdery in National Ideology Under Socialism, p. 133. For Ionescu’s bleak prophecy, see Radu Boruzescu, “Mémoire du Mal—Bucarest: Fragments,” in Martor: Revue d’Anthropologie du Musée du Paysan Roumain, No. 5 (2000), pp. 182–207.

↩ -

25

Note, though, that in 1991 the present prime minister (then foreign minister) committed himself to an eventual reunification “on the German model.” Likewise President Ion Iliescu, in December 1990, denounced the “injuries committed against the Romanian people” (in 1940) and promised that “history will find a way to put things completely back on their normal track.” See Charles King, The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture (Stanford University/Hoover Institution Press, 2000), pp. 149–150. The Romanian-speaking population of destitute Moldova would like nothing better. But Romania just now does not need to annex a country with large Russian and Ukrainian minorities, an average monthly wage of around $25 (when paid), and whose best-known export is the criminal trade in women.

↩ -

26

Repeal of anti-Jewish laws was the price of international recognition for the newly independent Romanian state in 1881. In 1920 the Versailles powers made citizenship rights for Jews and other non-Romanians a condition of the Trianon settlement. In both cases the Romanian state avoided compliance with the spirit of the agreement, but nonetheless made concessions and improvements that would not have been forthcoming without foreign pressure.

↩ -

27

R.W. Seton-Watson, A History of the Roumanians (Cambridge University Press, 1934), p. 554; also cited in King, The Moldovans, p. 36.

↩ -

28

E.M. Cioran, “Petite Théorie du Destin” (from La Tentation d’Exister), Oeuvres, p. 850. The French original reads: “Il y a des pays qui jouissent d’une espèce de bénédiction, de grâce: tout leur réussit, même leurs malheurs, même leurs catastrophes; il y en a d’autres qui ne peuvent aboutir, et dont les triomphes équivalent à des échecs. Quand ils veulent s’affirmer, et qu’ils font un bond en avant, une fatalité extérieure intervient pour briser leur ressort et pour les ramener à leur point de départ.“November 1, 2001An election flyer for Corneliu Vadim Tudor’s Romania Mare (Greater Romania) Party, listing twelve famous Romanians—“Apostles of the Nation”—who died violent deaths “on the Altar of the Fatherland.” In addition to Vlad Tepeåüs (Dracula) and Nicolae Ceauåüsescu, note the presence of Ion Antonescu, the wartime dictator and ally of Hitler.

↩