In the mid-1980s I made occasional trips to Harbin in Manchuria to report on the Orthodox White Russians who lived there, the remnant of a community that had fled from the new Soviet Union after the revolution. There were once so many of them that parts of Harbin resembled a Russian city. But the upheavals of the Japanese occupation and the Cultural Revolution, emigration, and death had reduced the community to a few dozen by the time I arrived. They attended a restored church with an onion dome where the priest, a handsome young Chinese with a basso profundo voice, was feared by his congregation, who told me they suspected him of being a police spy.

The congregation, still dressed traditionally, with the women in headscarves and the men in boots, was so old and fragile that some could barely stand during the services and would suddenly collapse onto their seats. I became friendly with an eighty-eight-year-old woman who lived alone in a room decorated with a few things from Russia, from which she had fled in 1921 with her husband, a veteran of the tsar’s defeated army. He was dead and her daughters had managed to emigrate. One lived in Philadelphia.

I felt sorry for this lonely old woman, whose husband’s grave had been despoiled during the Cultural Revolution when Red Guards wrecked the foreign cemetery. I said that I would try to help her to leave Harbin and settle with her daughter in Philadelphia. She raised her hands as if in prayer. “Please don’t do that. I spent two years there and came back to Harbin. I’d rather be here.”

For her meticulous and fascinating study of the Slavs—Russians, Ukrainians, Poles—and Jews who lived in Shanghai from the early Twenties until well after the Communist victory in 1949, Marcia Reynders Ristaino has made use of Chinese, Japanese, German, Russian, and English sources to describe the survival of a refugee community that at one time numbered over fifty thousand people. What interests Ms. Ristaino, the senior Chinese acquisitions specialist at the Library of Congress, is

the story of a collection of refugee communities, each consumed by the daily struggle to survive under often overwhelming economic, social, and cultural disadvantages. The daily toll on individual energies and spirits was great. Nevertheless, each community managed to preserve its separate ethnic and cultural identities, one of the key priorities of the victim diaspora tradition.

Shanghai had many advantages for dispersed people such as the ones Ms. Ristaino describes. Control of the city had been wrested from the Chinese primarily by the British in the Opium Wars of 1839 and 1857. The purpose of the treaties that concluded these wars was to open China to foreign trade and exempt foreign merchants from Chinese law; what rapidly emerged was foreign political jurisdiction in what became known as the International Settlement and the French Concession. By World War I foreign powers controlled eight thousand acres of Shanghai. The Western nations did not yield their control over a considerable part of China’s largest city until after the start of World War II.

In fact Western administration of the settlements was fairly informal; there were virtually no immigration controls, which made Shanghai attractive to many different immigrants. There had been a small community of Jews from Baghdad in Shanghai since the early nineteenth century. Some, like the Sassoons and the Kadouries, became very rich, and still prosper in Hong Kong. They had made their fortunes in opium, tea, silk, wool, and cotton, before moving into trams, breweries, banking, and finance. In 1900 they numbered fewer than one hundred families.

So nebulous was Shanghai’s jurisdiction that even after it came under partial Japanese occupation in the late Thirties, European Jews fleeing Nazi persecution continued to arrive there in large numbers. These Jews, whose number eventually exceeded 18,000, joined the more than 30,000 Russians, Poles, Byelorussians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, and Latvians who had fled Russian and Soviet oppression. As Ristaino says, we don’t know the precise numbers of refugees, but taken together this made up a group twice as large as the British, French, and Americans in the long-established Shanghai foreign community, which had led a privileged expatriate life with exclusive clubs, churches, a racetrack, theaters, and restaurants. The Europeans looked down on the refugees as “the other Shanghai”—until, like the Baghdad Jews, they could buy their way into social acceptance.

But the number of foreign residents was dwarfed, as Ristaino says, by at least 150,000 Chinese refugees who had fled the disorders and wars that had beset China since the 1850s. Ristaino only briefly touches on this vast social hinterland; but she observes that the sufferings of the Shanghai Chinese refugees were far more bitter than those of the Europeans, who, for their part, paid little attention to the local people except as servants or laborers. This insensitivity of the foreigners to the plight of the Shanghai Chinese, whether regular residents or refugees, is not surprising when it comes to the well-off expatriates. As for the incoming European refugees, whether Slavs or Jews, Ristaino writes, they “quickly became an underclass in the foreign community.” While they did not

Advertisement

seriously threaten the livelihoods of the Western elite, they were a source of embarrassment for the Westerners, in that these impoverished refugees were white and yet willing to do menial labor alongside Chinese. Their presence seemed to put a substantial dent in the social armor of the white Westerners and threatened to undermine what was widely perceived as their racial superiority.

In 1937 the Japanese, in de facto control of much of Shanghai, began dismantling Western rule over the city, and by 1941 they were interning the Western elite. Most of the Jews stayed in enclaves, which were not traditional ghettos—they were not forcibly confined to them—while the Slavs remained more or less free to live where they wished.

The Shanghai described in Port of Last Resort was a unique, often bizarre, place.1 Within its less than thirteen square miles immigrants could sink into prostitution, crime, despair, and suicide, or maneuver themselves into various conditions of prosperity, or at least survival. The Jews, no matter how sad and disappointing their shattered families and hopes, had escaped German and East European persecution, but they were always aware of what might still happen to them. By the late Thirties there were agents of Nazi Germany among the 3,000 Germans in Shanghai. One of them, later known as “the Butcher of Warsaw,” was hanged in Poland after the war.

Many of the Germans were violently anti-Semitic and eager to persuade the Japanese to deal harshly with “the Jewish question.” But Ristaino shows that in the Jewish enclaves there were synagogues, schools, publishing houses, book stalls, theaters, and small businesses. Many of the Germans, she writes, made frequent outings to Hongkou, the main Jewish enclave, “in order to enjoy the familiar life and entertainment in its cafés and shops. Hongkou reminded even the anti-Semites of home, offering the kind of food and goods they liked and renewing their cherished connection with German culture and traditions.”

It was the Jews’ preservation of this culture in the midst of their own continued bickering among different degrees of orthodoxy, nationalities, professions, and cultural backgrounds that enabled them to survive as well as they did. Ristaino has searched official records, examined their diaries and letters, and interviewed some survivors. For most Slavs, by contrast, who also bickered and conspired against one another, life in the settlements tended to be miserable. With few exceptions they were poor and saw themselves as social and political outcasts. The Slavs’ political weakness, Ristaino notes, lay primarily in their leaders, some of them former White Russian senior officers who brought with them their pre-Shanghai factionalism and provoked antagonism by claiming to speak for all Russians, or all Poles, or all Ukrainians. The Slavs also imagined they might return some day to the countries from which they had fled, an illusion sustained by few Jews. Unlike the Jews, the Slavs who finally emigrated from Shanghai rarely if ever hold reunions.

“In the end,” Ristaino emphasizes, “Judaism enabled the Jewish diaspora in Shanghai to overcome its major differences and sustain itself as a community.” Despite the discrimination against them in Shanghai and despite considerable differences among the assimilated German Jews, the religious Jews from the Baltic states (whose yeshivas made Shanghai a center of traditional Jewish learning), and the Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews, there was, Ristaino writes,

a layering of identities: one might be a stateless German, be of the Ashkenazi tradition, have a certain level of income, skill, or education…. In the end, being Jews put them in touch with a tradition, networks, resources, and an encompassing identity that was sustaining even in the worst of times.

Ristaino does not avoid the details of those bad times. At one point, one quarter of the younger Russian women in Shanghai were full- or part-time prostitutes, so many indeed that the League of Nations issued a shocked report on them. Jewish women, too, worked as prostitutes to support their families, and some husbands left their tiny flats so that their wives could entertain their clients.

Ristaino’s account is particularly revealing in showing how the Japanese declined to follow German practice and persecute the Jews. This became a major point of contention between the Axis partners. Japan’s policy was, Ristaino says, “highly ambivalent.” One factor was the lingering gratitude of the Japanese toward the American-Jewish tycoon Jacob Schiff who, during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, had organized $410 million in loans to the Japanese side—about one half of Japan’s total expenditure on the war. Schiff thought he was helping defeat a regime that was persecuting Russian Jews. So grateful were the Japanese that Schiff was granted an audience with the emperor. (The loans increased Russian anti-Semitism. Ristaino quotes from the diary of a Russian veteran of the war: “We know you [the Jews] sold us to the Japanese.”) Many of the 30,000 Jewish conscripts in the tsar’s armies, who could not become officers, began the flight of Russian Jews to Harbin in Manchuria and thence to Shanghai.

Advertisement

Quite apart from the Schiff loans, by 1937 Tokyo began to consider a role for Jews in Japan’s expanding empire. The Japanese were urged on by Dr. Abraham Kaufman, president of the Hebrew Association of Harbin, whom the Japanese invited to form an umbrella organization of all Hebrew groups in China and Japan. He complied, in part to secure Japanese help in limiting the widespread anti-Semitism among the Harbin White Russians. He hoped, too, according to Ristaino, to persuade the Japanese to help Jews fleeing Europe settle in East Asia. In December 1939 Kaufman, now the organizer of Jewish groups from Central Asia to Kobe, wrote to the Japanese emperor thanking him for the unprejudiced protection enjoyed by Jews living in East Asia. He suggested that further protection would cause international Jewry to be grateful; for their part, the East Asian Jews would promise support for the Japanese New Order. The Japanese saw the possibility of Jewish financial help, especially from the US, for what came to be known as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.2

At first the Japanese had been suspicious of the Jews. A Japanese cabinet-level committee, which had read the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, concluded that an international conspiracy of Jewish financiers was working to oppose Japan’s plans for China. This was true of Sir Victor Sassoon, the most prominent of the Baghdad Jews in Shanghai and a major supporter of Chiang Kai-shek. But other Japanese officials, including officers like Colonel Yasue Norihiro, who had translated the Protocols into Japanese, told military and Foreign Ministry officials in 1938,

Obviously we should not follow Germany’s example…. We should protect them [the Jews] and let them enjoy the benefits of our imperial prestige…. I do not see any reason why we should have them as an enemy…. Through the Jews in the Far East, we can advertise our hospitality to [American Jews]….

A committee chaired by Prime Minister Konoe concluded that “extreme persecution or rejection [of Jews] as practiced by Germany would be contrary to the spirit of equality for all races that our Empire has been advocating.” Because Japan needed “to introduce foreign capital for economic construction,” it should avoid worsening relations with the US.

By June 1939 the president of the Shanghai Ashkenazi Jewish Communal Association, Morris S. Bloch, had written to the American philanthropist David A. Brown that there was “not a better nor a richer country in the world” than Manchukuo, the Japanese puppet state in Manchuria. Shanghai’s Ashkenazi leaders were enraged by Sassoon’s claims that Japan’s corrupt government was so unpopular that the Japanese people might rise up against it; they issued a statement describing the Japanese as “humanitarian and unprejudiced,” and insisted that “irresponsible statements of private individuals” should be ignored.” A navy captain, Inuzuka Koreshige, the officer in charge of liaison with the Shanghai Jews and a “serious researcher and author of studies on the Jews,” supervised a plan to settle thirty to seventy thousand Jews in Shanghai over the next two decades, using a huge projected sum from American Jews, some of it to be used for securing jobs for the Jews and the rest to finance iron, lathes, and fuel for Japan “without conditions.”

Inuzuka helped arrange the entry to Shanghai of the Polish and Baltic yeshivas, consisting of one hundred students and their rabbis, and he was repeatedly entertained and thanked by members of the Jewish community. After Pearl Harbor, when all the plans for American help collapsed, Inuzuka and Colonel Yasue were recalled to Japan. Inuzuka, honored during his farewells as a “friend of the Jews,” was invited to become the honorary president of the Shanghai Hebrew Society for the Study of Nipponese Culture. Inuzuka was no friend of the Jews; but he had believed that by not persecuting them Japan might receive financial support from American Jews.

The ambivalent Japanese attitude toward the Jews, a combination of admiration and fear, Ristaino contends, led to Japan’s establishment of the Shanghai ghetto, in which the Jews could sustain their own cultural life and survive better than the Shanghai Slavs, not to mention the Jews’ friends and relatives in Nazi-occupied Europe.

No part of this Japanese encounter with the Jews is more remarkable than the career of the diplomat Sugihara Chiune, referred to nowadays as “the Japanese Schindler.” Working in the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Latvia, he saved six to ten thousand Jews in 1939 and 1940 by issuing transit visas enabling them to escape to Japan and from there to the Dutch possessions in the Caribbean and other places of safety. Sugihara is often described by Jews and Japanese as a brave man who defied orders from Tokyo. Ristaino argues convincingly that Sugihara was in fact following the government’s policy of favoring Jews. Such instructions were issued as well to Japanese consulates in Manchuria, Mongolia, and Vladivostok. It appears that Sugihara’s career was not, as some have claimed, damaged by saving the Jews; he went on to serve in other important posts.

Fluent in German and Russian (he was a convert to Russian Orthodoxy), Sugihara was probably an intelligence agent reporting on German and Russian military plans. When he finally returned to Japan in 1947, after almost two years in Soviet internment, he was suddenly ordered to resign from the diplomatic service. He then spent many years working for Japanese firms in Moscow and, according to Ristaino, “it seems not inconceivable that he actually left the Foreign Ministry in order to become a spy for Japan in Moscow.”3 None of this makes Sugihara less admirable.

When the Pacific war ended, the Shanghai Jews, who had feared some sort of cataclysm in the final weeks before the Japanese surrender, burst out of the ghetto and for weeks, in the words of a young Jew, were “in a most jubilant state.” The Americans arrived accompanied by vast quantities of aid and a need for clerks, secretaries, drivers, craftsmen, and mechanics, which both Slavs and Jews could supply. Help for the European Jews came from international Jewish organizations. Neither the Slavs nor the Chinese population enjoyed such good fortune, although the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) sent more help to China than any other country. Amid runaway inflation and corruption, a potential scandal arose: UNRRA officials declared that Chinese had been “inured for generations to stoical acceptance of cold, rags, disease, and hunger.” European refugees, therefore, received more than Chinese refugees, but it was officially arranged that “UNRRA reports on this operation would be distributed only outside China.”

For many of the Russians, who had been overwhelmingly anti-Soviet, the German invasion brought about new sympathy for the Motherland. Moscow was urging them to return and visas, even for known White Russians, were easy to obtain. Hearing that churches were being reopened and that officers now, as in tsarist times, were wearing epaulets, four thousand Shanghai Russians returned only to find themselves persecuted, and sometimes consigned to camps; when news of their hardships reached Shanghai many Slavs claimed stateless status. Anti-foreign sentiment was growing in Shanghai, where the desperate Chinese wanted to occupy the Europeans’ apartments and houses. Of the European Jews, Ristaino writes, 40 percent wanted to go to the US. Twenty-one percent preferred to go to Palestine, which was still closed to them. Five thousand German-born Jews in Shanghai had no difficulty emigrating to the US. The Baltic yeshiva Jews, supported by a powerful American lobby, received priority visas. But Shanghai Jews born in other countries with small quotas for admission to the United States were competing for entry with 750,000 Jewish displaced persons from Europe. In 1947 6,670 Shanghai Jews were still unsure of their futures. Some 2,676 left for Israel. In 1950 twelve hundred Jews remained in Shanghai.

Some Russians and Ukrainians were welcomed by Australia and Argentina. Special legislation brought Shanghai Russians who were considered to have escaped Chinese communism to the US. In 1951, when the last of them arrived in San Francisco, one refugee said, “The remnants of Old Russia, unshakable in their fundamental principles…have been trying for thirty-three years to build up their new lives…. Let us all be worthy of this, to obtain rights without obligations may destroy all that has with such hardships been gained and will create a wrong impression concerning the bulk of White Russian Refugees from China.” In 1956 there were 171 Jews left in Shanghai. In 1955, 110 of them had left for the Soviet Union. Their lives proved to be so difficult that the following year only ten made the journey. In 1967 fifteen Jews were reported in Shanghai, and in 1982 the Hong Kong South China Morning Post reported the death of the last Shanghai Jew. In one of her final passages, Marcia Ristaino makes what I found to be her only mistake. When the last Pole died, she says, there was left “only one person from the foreign refugee community in all China, an elderly woman in Harbin.” She probably has in mind the last Jew. There were over thirty Orthodox Russian refugees living in Harbin in the late Eighties.

Ms. Ristaino has written a remarkable book. She describes well the lives of heroes, villains, spies, collaborators, prostitutes, and many other people simply doing their best to survive. The vast numbers of Chinese, whose situation in Shanghai was overwhelmingly more desperate and hopeless than that of the Jews and the Slavs, are only a bleak, silent presence in her book, but they are not Marcia Ristaino’s subject. She has been able to reconstruct a largely ignored history of suffering, fear, alienation, and appeals to God by people far from home. When we look at the lives of the tens of thousands of Shanghai refugees, and particularly the lives of the Jews, many had happier endings than they ever expected.

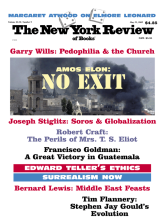

This Issue

May 23, 2002

-

1

Its character in the period of foreign domination has been colorfully and expertly portrayed, for example, in Lynn Pan, Shanghai: A Century of Change in Photographs, 1843–1949 (New Amsterdam Books, 1990); Shanghai Sojourners, edited by Frederic Wakeman Jr. and Wen-hsin Yeh (Institute of East Asian Studies, 1992); Frederic Wakeman Jr., Policing Shanghai, 1927–1937 (University of California Press, 1995) and The Shanghai Badlands: Wartime Terrorism and Urban Crime, 1937–1941 (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

↩ -

2

Only a year before, however, the president of the American Jewish Congress, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, wrote to a colleague of Kaufman’s: “I think it wholly vicious for Jews to give support to Japan, as truly fascist a nation as Germany or Italy…. I promise that everything I can do to thwart your plans I will do.”

↩ -

3

For accounts emphasizing Sugihara’s heroism, see Hillel Levine, In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked His Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews from the Holocaust (Free Press, 1996); and Yukiko Sugihara, Visas for Life, translated by Hiroki Sugihara (Edu-Comm.Plus, 1995). Ristaino mentions also Dr. Ho Fang-shan, the Chinese consul general in Vienna, who from 1938 to 1940 issued “thousands of Shanghai exit visas to fleeing Austrian Jews.” Unlike Sugihara, apparently, Dr. Ho defied the orders of the Chinese ambassador in Berlin. Not long ago the Taipei government wished to honor the memory of Dr. Ho, “the Chinese Schindler”; his family refused because the Kuomintang, the ruling party in the government in 1940, had treated him badly.

↩