1.

Taybeh is a small Palestinian village in the West Bank, ten miles northwest of Jerusalem. The farmhouses that you pass on the road there, the domes of the abandoned caravanserai, the minarets of Ottoman mosques—all are built of honey-colored limestone which changes tone according to the color of the sky. Shepherd boys lead their flocks down steep olive slopes into the strip fields of the valleys; it could almost be Tuscany. Only the concrete phalanx of fast-expanding Israeli settlements on the hilltops reminds you where you are, and brings you back to the tensions and violence that are inescapable here. With their towering cranes and half-built apartment blocks and long lines of solar panels glinting on their roofs, the settlements are surrounded by swarms of yellow bulldozers ripping through the ancient landscape. At the settlement gates sit nests of razor wire, the fortified emplacements of the Israeli army.

The first thing that you notice about Taybeh as you drive in is that the village is full of churches: it is in fact one of the last villages around here still dominated by Palestinian Christians. The second thing you see is that Taybeh has a new brewery, and that the brewery produces (as its signboard proudly proclaims) the only organic beer in the Middle East.

The brewery is the brainchild of Nadim Khoury, a small middle-aged man with an appropriately beery paunch, tight shorts, and dazzlingly white socks tucked into his Nikes. He has a Boston accent and a baseball hat, both dating from the years he spent in the States, first at high school on the East Coast, then learning the business of brewing in California. He made the decision to return home to Palestine in 1993 when the Oslo Accords were signed, to start what he hoped would be Palestine’s answer to Sam Adams. The Israeli military authorities who had governed the West Bank had always blocked his application to open a brewery, but the Palestinian Authority gave him a license within a month. By 1995 the brewery was in business.

For the Christian Palestinian diaspora it was a good time to return. On the wave of optimism that followed Oslo, tens of thousands of middle-class West Bank exiles—many of them from the Palestinian Christian business elite—sold their property in the West and returned home to invest their life savings in the new Palestine. They ranged from recent university graduates to Palestinian multimillionaires who had built up fortunes in the Gulf. There are no exact figures for the amount of private money that flowed back into the West Bank and Gaza during the Nineties but it amounted to several billion dollars, with at least $300 million a year coming in throughout the decade.

Overnight, the landscape changed. Bethlehem, Nablus, and Ramallah are all towns which contain the sprawling refugee camps we know from the news reports, places whose hopelessness breeds the young men and women willing to become Hamas suicide bombers. But side by side with these places, featured far less frequently in the press and television, are new well-to-do middle-class suburbs, where highly educated US and Gulf returnees have settled down in what was, at least until the outbreak of the second intifada, considerable comfort. Even now as you drive through the streets, beside pockets of desperate poverty around the camps, you still pass gleaming CD shops and art galleries, fitness clubs and cappuccino bars. You can even find a Mercedes sales office in Ramallah.

“When we came back, we put in all the family savings,” I was told by Khoury as he showed me the sprawling villa he had just built beside the brewery. Over the door was a tympanum showing Saint George lancing the Dragon; to one side was a deep blue swimming pool: “We took the kids out of high school in Boston and made a nice house for them here. At first things went well,” he said. It was only later that they “didn’t work out like what we had expected.”

Khoury says he always knew that persuading Palestinians to stop drinking Israeli beer was going to be a struggle: “People had developed a taste for this mass-produced stuff. It was always going to take time to educate them about drinking local, naturally produced ale with no additives.” What he did not expect was the difficulties he would have from his more puritanically minded Islamist compatriots who blocked him from selling alcohol in Gaza. Thanks to pressure from Hamas, Gaza is now more or less free of alcohol, though the Palestine Authority has never officially declared that it should be.

But the problems he faced from other Palestinians were nothing like those he faced from the Israeli army once the second intifada broke out in 2000. His production had grown from 200 crates a week in 1995 to 1,200 crates by the end of the decade. Suddenly he found that he couldn’t get his beer out of the village. The Israel Defence Force (IDF) had blocked the roads and would not let his vans out of Taybeh. On the occasions they did, or if he managed to persuade Israeli haulers to distribute it instead, it would still not be allowed into Nablus, Bethlehem, or Ramallah, his three main markets: “The beer would sit at the checkpoints in the sun for days,” Khoury says. “If the IDF didn’t drink or steal it themselves, it would go off in the sun: it has no preservatives. We are now down to 10 percent of what we were producing in 1999. I’ve laid off all our staff and would be bankrupt now if I had borrowed money. We’re only here still because it was family money we used.”

Advertisement

Khoury gestures to his empty factory and the silent machinery: “But there is no question of going back to Boston,” he says. “You just have to hope. Every day I pray to Saint George. It’s too late to give up.”

Khoury’s dilemma is in some ways a parable of the problems that have always been faced by Palestinian Christians, stuck as they are between their Muslim compatriots—with whom they share many linguistic, cultural, and ethnic traditions—and their Israeli governors, who if they are aware of their existence at all, tend to treat them just as they do other Palestinians: as security hazards and as unwelcome neighbors, to be controlled, kept out, avoided, or ignored.

2.

The Christian community in Palestine is a very ancient one: like the Copts of Egypt, the Palestinian Christians of this area never converted to Islam at the time of the Arab conquest in the seventh century AD, though they did in time take on their conquerors’ language and learn, like their Muslim neighbors, to call their God Allah. Ethnically, they derive from the many different peoples—Canaanites, Jews, Philistines, Byzantines, Bedouin Arabs, Crusaders, European traders, and so on—who have passed through this region since prehistory. During the Byzantine period, when the region was almost entirely Christian, the hinterlands of Palestine were so densely filled with Christian monks and monasteries that, according to one chronicler, “the desert had become a city.” Even as late as the eleventh century, Christians probably still outnumbered Muslims in Palestine: it was the eruption of the Crusades, and the backlash that followed the eventual Muslim victory, that put an end to that.

By 1922, only twenty-six years before the founding of Israel, Christians still made up a full 10 percent of the population of British Mandate Palestine. They were better off and better educated than their Muslim counterparts; they owned almost all the newspapers and filled a disproportionate number of jobs in the Mandate Civil Service. While numerically they still dominated the Old City of Jerusalem, their leaders had already moved out from the narrow streets around the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to build fine villas for themselves in the West Jerusalem suburbs that now house the richest Israeli businessmen. But today the Christians are in retreat, and Taybeh is one of the last major Christian centers left in Palestine. Many are finding that they have no choice except to leave.

This diaspora is part of a wider exodus of Christians from all over the Middle East. For several hundred years under the capricious thumb of the Ottoman sultan, the different faiths of the Ottoman Empire lived, if not in complete harmony, then at least in a kind of pluralist equilibrium. Islam has traditionally been tolerant of religious minorities, and the relatively benign treatment of Christians and Jews under Muslim rule contrasts with the fate of Christendom’s one distinct religious minority, the relentlessly ill-treated European Jews. As recently as the seventeenth century, Huguenot exiles escaping religious persecution in Europe wrote admiringly of the Ottoman policy of religious tolerance: as one of them put it, “There is no country on earth where the exercise of all religions is more free and less subject to being troubled, than in Turkey.” The same broad pluralism that gave refuge to the Jews expelled by the bigoted Catholic kings from Spain and Portugal protected the Eastern Christians in their ancient homelands. A century ago, a quarter of the population of the Levant was still Christian; in Istanbul, that proportion rose to almost half.

But with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century, its fringes—the Balkans, Cyprus, eastern Anatolia, the Levant—have suffered decades of bloodletting. Everywhere pluralism has been replaced with a savage polarization. Religious minorities have fled to places where they can be majorities, and others have abandoned the region altogether, seeking out places less heavy with history, such as America or Australia. In the Middle East today the Christians are a small minority of 12 million, struggling to keep afloat amid 180 million non-Christians, with their numbers shrinking annually. In the past twenty years, at least three million have left to make new lives for themselves in the West. According to the historian Professor Kamal Salibi, the Christians have simply had enough: “It’s a feeling,” he told me in Beirut, “that fourteen centuries of having all the time to be smart, to be ahead of the others, is long enough. The Arab Christians tend to be intelligent, well-qualified, highly educated people. Now they just want to go somewhere else.”

Advertisement

For the Palestinian Christians, their diaspora began in the Nakba—Catastrophe—of 1948. In the fighting that led to the creation of the State of Israel, 70 percent of the Palestinian Christians, along with around 700,000 of their Muslim compatriots, fled or were driven out of their ancestral homes into exile abroad. During the Six-Day War of 1967, a second exodus took place: a further 18,000 Christian men, women, and children fled. Since then the Christians of the Palestinian territories have continued to emigrate. In Ramallah 66 percent of the Christians have gone; in Bethlehem it’s just over 50 percent. Seventy-two Christian families—nearly three hundred people—emigrated from Bethlehem last year alone. Today Christian Palestinians make up less than 2 percent of the population of Israel-Palestine. Every year their proportion of the population decreases as the hemorrhage of Christians is matched by the influx of Israeli settlers. There are now said to be more Jerusalem-born Christians in Sydney than are left in Jerusalem. More Bethlehemites live in Chile than Bethlehem.

It is the same throughout the West Bank. Most of the young Christians I met already had made applications with one embassy or another. Being on the whole middle-class professionals, they find it easier to leave, have the money and the skills to start again, and find their applications getting preferential treatment. Canada is now the current destination of choice, the US being perceived as too Arabaphobic even for Christian Arabs.

In Bethlehem, which has the largest Christian community in the area, I met a Christian cameraman who had worked with the BBC but lost his job after Bethlehem was put under extended curfew. “Everyone who can has plans to emigrate,” he told me. He pointed toward the wall of new settlements encircling Bethlehem. Huge Israeli Merkava tanks were dug in under camouflage netting, their guns pointing out over Bethlehem’s churches and mosques, bazaars and piazzas. “Frankly, at the moment, you have to be crazy to live here if you have a choice.”

Either way, the people who are going are the young, the bright, the technocrats, and the moderates: exactly the people both Palestine and Israel will need to bring prosperity to any future state if a peace solution is ever found. Ironically, of course, this exactly mirrors the situation across the battle lines in Israel, where there is also a steady drain of liberals emigrating from the country in an attempt to escape the rival fanaticisms of the conflict. In the long term it sometimes seems as if it will just be the fundamentalist settlers left to confront their opposite numbers in Hamas, with fewer and fewer secular moderates remaining to keep the crazies on both sides from each other’s throats.

This emigration matters. The Christian Arabs have always protected the Arab world from the extremes of political Islam. Since the nineteenth century, they have taken a vital part in defining a secular Arab identity: men like Michel Aflaq, founder of the Ba’ath Party, and George Antonius, who wrote The Arab Awakening, were both Christian. Edward Said, the most influential contemporary intellectual in the Arab world, is also a Palestinian Christian. If the Christians continue to emigrate, the Arabs will find it much harder to defend themselves against radical Islamism.

There is another reason to lament the emigration of the Christian Arabs. Christianity is not a Western religion. It was born in Jerusalem and received its intellectual superstructure in cities such as Antioch, Constantinople, and Alexandria. At the Council of Nicea, where the words of the Creed were thrashed out in 325 AD, there were more bishops from Persia and India than from Western Europe. Those Eastern Christians who are now leaving the Middle East preserve many of the most ancient liturgies and traditions still surviving from the early Church. Without the local Christian population, the most important and ancient shrines in the Christian world will be left as museum pieces, preserved only for the curiosity of tourists. Christianity will no longer exist in the Holy Land as a living faith.

3.

The Christians have a variety of reasons for leaving. A few admit that they are worried by the rise of militant Islam, and fear that in time their place in Palestinian society may be under threat as the Muslim Palestinians become increasingly radicalized. As recently as the early years of the twentieth century, Muslim, Jewish, and Christian Palestinians would still come together, as they had done for centuries, to pray at saints’ shrines common to all the three faiths. One of these was the Church of St. George in Beit Jala on the West Bank where Jews and Muslims would join their Christian neighbors to pray to the saint the Muslims knew as al-Khadr and the Jews as Elias. Today the Jews are nowhere to be seen. Muslim Palestinians still come, but fewer each year. This polarization seems irreversible.

The biggest problem facing the Christians is that America is Christian too. Whatever its Eastern origins, today Christianity’s center of gravity is firmly in the West. The remaining Eastern Christians now find themselves caught between their coreligionists in the US and their strong cultural and linguistic links with their Muslim compatriots.

Nothing does more to unite the fractious Islamic world, or to turn it against its Christian minorities, than a US attack on one or another prostrate Muslim state. The US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq are exactly the sort of adventure that the Eastern Christians have learned to dread, and, as at the time of the Crusades, it is they who are getting persecuted for what is seen as the aggression of the Christian West. So far the only Christian communities to have been directly targeted by militants in revenge for US attacks are the Egyptian Copts and Pakistani Protestants, both of whom have been gunned down in Islamist attacks, sometimes while in church. But with the continuing radicalization of the Palestinian Muslims it is now far from inconceivable that the same could eventually happen in Palestine.

Yet the Palestinian Christians all insist that it is not their Muslim neighbors that are causing them to emigrate, so much as the brutality of the Israelis: “I don’t know one family which has left because of the Muslims,” I was told by Carol Michel, a young Palestinian Christian working in the Lutheran International Center in Bethlehem. “It’s the Israelis that have turned Bethlehem into a big prison. We are locked in and cannot leave. Every year they grab more of our land. All I want is a normal life. I love Bethlehem—but I want to live, to be free again. Every year my father said the next year would be better. But now he’s sixty-four and it’s still getting worse. I don’t think anyone in the West realizes how we suffer here. Our only hope is to emigrate.”

The emigrating Palestinian Christians repeat the same grievances: they are leaving to escape the curfews, the arrests, the targeted (and sometimes untargeted) killings, the midnight searches, the house demolitions, and the constant petty humiliations inflicted on them by the Israeli occupation troops. They leave to escape the forcible expropriation of their land, the diversion of water from ancient Palestinian villages to the new Israeli settlements, the continual closure of schools and universities. Most of all they flee the lack of hope: the growing awareness that the second intifada has failed, that Arafat and Oslo are finished, that the road map looks unworkable. There is a nagging fear that the US might eventually, tacitly, consent to some right-wing Israeli government ethnically cleansing the remaining Palestinian population.

Since the beginning of the disastrous second intifada, unemployment has risen to 65 percent and everyone has accumulated debts. Increasingly, people have no money for food, and rely upon coupons distributed by the Red Cross. Even many of the middle class find they lack food. Things were especially bad last December, when, following a rash of suicide bombings, for six weeks the Israelis broke the curfew of Bethlehem only for an hour or two, twice a week—giving no time even for family shopping. Just before last Christmas, I spoke to my former landlady in Bethlehem, a relatively prosperous Roman Catholic, who told me over the phone that she only had water and crackers to live on until the next break in the curfew: “For once I hope that the Israelis won’t lift the curfew during Christmas,” she added. “We don’t have money to buy my kids presents.”

What really rattled the Christians in Bethlehem was the muted response of the West to the Israeli siege of the Church of the Nativity last year: “Why did the Christians in the West not try to help us?” asks Fuad Kokaly, the mayor of Beit Sahour, just below Bethlehem. “We feel we have been abandoned.” Like most of his community Kokaly was profoundly depressed by the way much of the press and television uncritically bought the Israeli line that Muslim “terrorists” had taken the priests hostage. According to Palestinian priests involved in the siege, they had chosen to stay with the besieged Palestinians they had grown up with, several of whom were their own Christian parishioners. “Western Christians have a duty to secure our future,” says Kokaly. “This is the Holy Land, the land of the Nativity. Sometimes we think the Western Christians have simply forgotten their brothers in the East.”

While the siege was going on, Israeli troops occupied Bethlehem, and made their presence felt. Much damage was done. New Russian immigrants in the IDF, many of them fresh from the war in Chechnya, behaved particularly brutally. One of the worst cases of vandalism was the destruction of a new arts and conference center run by the Lutheran Church. The pastor, the Reverend Mitri Raheb, showed me how Israeli troops had smashed up the $2 million center, blowing up workshops, shattering windows and fax machines, shooting up the photocopiers, and bringing down ceilings with explosive charges in an oddly pointless bout of thuggery.

The pastor described to me how on April 5, 2002, drunken Russian-speaking IDF soldiers held him at gunpoint for six hours, making racist remarks about how ugly and filthy Arabs were, while they smashed up the center he had spent five years creating:

They destroyed everything. I told them this was church property and asked them why they were doing this. They said, “You Christians are siding with the Muslims and you will pay the price. If you were wise you would see that.” I replied, “The real wise man transforms his enemy into a neighbor, but you are transforming a neighbor into an enemy.” They just told me to shut up and pointed their guns at me. We complained to the IDF, and produced evidence that they had caused over half a million dollars of damage; but of course nothing happened. There was no compensation. There never is.

When you talk to the Palestinian Christians the question that constantly recurs is whether the time has finally come to leave. Bethlehem is now completely encircled with new Israeli settlements, and the new “security fence” has led to the confiscation of most of Bethlehem’s remaining agricultural land. And while the Israeli settlers can move freely over the West Bank, all the Palestinians are prevented by the IDF from leaving their towns. Many Palestinian business people are now on the verge of bankruptcy.

It never looked as if it would end this way. In 1998 after having been away from Palestine for ten years, Reem Abu-Aitah sold her computer business in Birmingham, England, and set one up in Bethlehem: “It was a great place,” she said. “We did it up. It looked really good: a nice open place you could walk around and choose your laptops and desktops. We’d just gone into profit when Sharon went to al-Aqsa….” in September 2000.

Within ten days our shop was caught in the crossfire between Bethlehem and [the Israeli settlement of] Gilo. We had to lie on the floor for hours watching the tracers shooting past. It was horrible. Bullets were hitting the walls…. One of our neighbors was killed, just sitting in her house.

Since then we have barely sold a single computer. No one has the cash for a new laptop, even if we could get them through the checkpoints. Occasionally we get calls from our suppliers in Tel Aviv and they’re saying, “Do you want an order?” They don’t seem to understand that we can’t even get out of our houses to go to the office without the Israeli army shooting us. Last month the shop was only open for three days. The rest was curfew. Many times I think of emigrating again. But the business keeps me here. We have invested everything. What can we do?

Some, however, have made a conscious decision to remain. Marwan Tarazi is one of the leading young Palestinian software designers: he helped design Arabic MS-DOS. A Greek Orthodox Christian, five years ago he returned home from an extended spell in Canada intent on rebuilding his country. “I earn about a quarter of what I used to in Canada, and of course it’s irritating not being able to go windsurfing and mountain biking like I used to in Montreal,” he says. “But my duty is here.”

Marwan’s current project is developing software for Bir Zeit University to allow the courses to be taught over the Internet so that students can continue studying under closure: “You can have all the curfews in the world,” he said, “but if you have a well-educated people, you have the basis for a developed country. The Israelis have closed down the schools and whole generations of kids are coming out with compromised educations. It’s going to have a catastrophic effect. But thanks to this program we already have Ramallah kids bedding down in the net cafés doing their courses while the IDF rampage outside. It’s working.”

Marwan shrugs his shoulders: “You’ve got to understand we are living in a horror show here. Its very easy to go nuts. You just have to keep believing in the future.”

Ten years ago, when I traveled around the West Bank talking to Palestinian Christians for my book From the Holy Mountain: A Journey among the Christians of the Middle East,1 it was difficult to find anything up to date written on the community, its history, and its current decline. Today that situation is very different.

Much the best book is Charles Sennott’s study The Body and the Blood: The Middle East’s Vanishing Christians and the Possibility for Peace.2 Sennott, a prize-winning correspondent for The Boston Globe, is a skilled, wise, and perceptive reporter with an unusually observant eye for small telling details: he notices for example how Palestinian Christian girls automatically put their pendant crosses away beneath their blouses when they pass through Muslim areas of Palestinian towns. They will not pass through such areas at all if they are wearing short sleeves or miniskirts. Sennott’s research is solid and reliable, and above all he is balanced and fair-minded: as a Boston Catholic whose wife is Jewish he has an empathy with both sides of the divide. Unusually for books that stress the plight of the Palestinians, it has received enthusiastic reviews in Israel itself.

Sennott emphasizes how few people outside the Middle East are even aware of the existence of Arab Christians: he points out that during Pope John Paul II’s historic pilgrimage to the Holy Land in March 2000, the indigenous Christians were overlooked, pushed aside, and forgotten. He also suggests that the final collapse of Palestinian Christian society seems imminent: already, he says, in one Jerusalem parish, there are no longer enough Christian men left to carry the coffin at funerals. The decline seems irreversible.

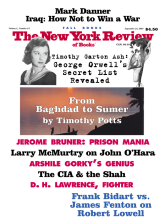

This Issue

September 25, 2003

-

1

Holt, 1997.

↩ -

2

If the book has a defect it is a lack of discussion of Palestinian Christian history. Fortunately several good books on the subject are available: see Anthony O’Mahony, The Christian Heritage of the Holy Land (Scorpion Cavendish, 1995), Palestinian Christians: Religion, Politics and Society in the Holy Land (Melisende, 1999), The Christian Communities of Jerusalem (University of Wales Press, 2003), and Christians in the Holy Land, edited by Michael Prior (World of Islam Festival Trust, 1994).

↩