I mean to say that mere romantic speculation on the power and beauty of machinery keeps it at a continual remove; it can not act creatively in our lives until, like the unconscious nervous responses of our bodies, its connotations emanate from within—forming as spontaneous a terminology of poetic reference as the bucolic world of pasture, plow, and barn.

—Hart Crane, “Modern Poetry” (1930)

1.

Emily Barton has written two remarkable novels in which advances in technology threaten the delicate equilibrium of a community. In The Testament of Yves Gundron (2000), Barton imagined a pre-industrial society on an island off the coast of Scotland, mysteriously untouched by modern civilization. In the village of Mandragora, “a man used a sharp stick to dig a hole for each seed, and furrowed his fields by dragging his fingernails through them and picking out each small stone.” Horses died young, asphyxiated when cords around their necks tightened as they pulled heavily laden carts balanced on a single wheel. Then a farmer named Yves Gundron, inspired by a dream in which he himself is dragging a cart, invents a harness, thus ushering in what he calls in his testament “the coming of the new world.” “Had I known then what terrors my invention would bring us along with its joys, perhaps I would have allowed the idea to drift off like a thousand other daydreams.” An anthropologist from Boston arrives in Mandragora followed by other inquisitive visitors. “Our newfound brethren are mad with questions,” Gundron ruefully concludes, “and everywhere they travel they send beams of light tearing through the countryside and our homes, which brightness strikes terror into my heart. I am done my inventing.”

Like The Testament of Yves Gundron, Barton’s splendid new novel, Brookland, has elements of fantasy, but the narrative sticks more closely to the historical record. Barton doesn’t specify her sources, but the germ of the novel is apparently a note jotted in a scrapbook in 1800 in which Jeremiah Johnson, a prominent citizen of Brooklyn—the village originally settled by Dutch emigrants and variously known as Breukelen, Breukland, Brookline, Brookland, and Brooklandia—reported an intriguing proposal:

It has been suggested that a bridge should be constructed from this village across the East River to New York. This idea has been treated as chimerical, from the magnitude of the design; but whosoever takes it into their serious consideration, will find more weight in the practicability of the scheme than at first view is imagined.1

The passive phrasing conceals the identity of the designer, but it has long been suspected that the visionary bridge was the brainchild of Thomas Pope, a craftsman from New York and a friend of Benjamin Latrobe, the architect of the US Capitol. In 1811, Pope proposed to build what he called a “rainbow bridge” across the tidal surge of the East River; the evocative drawing that accompanied his proposal, with sailing ships rocking in the roiling waters below the graceful cantilevered arch, is reproduced on the title page of Emily Barton’s Brookland.

In suggesting a completely different identity for the genius who came up with the design for the bridge in 1800, and in imagining the actual construction of the rainbow bridge, Barton has created a much richer story than can be pieced together from the shreds of information that have survived concerning Thomas Pope, who appears as a fringe character in Barton’s novel. Brookland is most obviously a historical novel, painstaking in its carefully researched and vividly imagined reconstruction of a vanished world, peopled by families with old Brooklyn names like Schermerhorn, Joralemon, and Hicks. But it is also a novel about the fragility of family ties, about ghosts—architectural as well as human—and about the sacrifices that artists are willing to make in order to fulfill their dreams. Two kinds of history went into the making of Brookland. One is the documentary record of social and political events that serve as background to the novel. The second kind of history is more specifically literary: the ways in which previous writers have evoked the crossing between Brooklyn and Manhattan.

2.

Bridge-building and its disappointments are at the heart of Brookland, Barton’s portrait of the artist as a young woman. The artist in Barton’s novel is Prudence Winship, and her dream is to build a bridge across the East River, connecting the distillery she has inherited from her father on the Brooklyn side to the markets of Manhattan on the other. Since John Augustus Roebling’s Brooklyn Bridge—suspended from cables rather than the cantilevered springboards Prudence imagined—wasn’t opened until 1883, and the action of Brookland is limited to the years between 1772 and 1822, we know from the outset that unless the narrative steps out of history altogether, Prue’s bridge is doomed to disappointment. That the novel nonetheless builds suspense across its considerable span is one of its many strengths. The human cost of the bridge, especially as it plays out among Prue’s extended family, is ultimately of more emotional impact than the fate of the unlikely structure of wood and stone that is constructed high above a 4,400-foot stretch of open water.

Advertisement

The Winship family, in Barton’s account, is firmly rooted in the early history of the American Republic. Matthias Winship, son of a prominent Puritan minister in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, escapes from the seminary by boarding a ship in Boston Harbor and sailing for “the West Indies, slaves, and rum.” An unbeliever, Matthias further defies his father’s expectations by learning to distill gin in England. He returns to America with his dissenting English wife, Roxana—“half melancholic and half minx”—and they settle in the still-rural farming village of Brookland, a convenient location for shipping gin to Manhattan or up the Hudson. The Winships have three daughters, and give two of them traditional Puritan names, Prudence and Temperance, as a profane joke. In the absence of a male heir, Prudence is trained to run the distillery in partnership with Temperance, a sturdy helper when she’s sober. Prue eventually marries a kindly surveyor named Ben Horsfield; “Tem,” a beautiful woman with raven-black hair, refuses all suitors, most notably the flashy dresser Ezra Fischer, the lone Jew in the community, who runs a ferry across the East River—the ferry that any successful bridge will render obsolete.

A third sister, Pearl, is born without a voice. Prue is convinced that Pearl’s dumbness is the result of a curse that, jealous of her parents’ attentions, she uttered before Pearl’s birth; she carries this guilty conviction into her adulthood, and it colors her ambivalent feelings toward her younger sister. Pearl wears a little silver-bound book around her neck by means of which she communicates her cryptic thoughts. She turns out to be a gifted artist as well. With her black hair, sloe-eyed expression, and diminutive body, Pearl is—as the other characters often note—an “uncanny” presence in the novel. In his essay “The Theme of the Three Caskets,” Freud wondered why the third sister in folk tales and literature is so often reticent or dumb, like Cordelia in King Lear or Offenbach’s La Belle Hélène: “La troisième ne dit rien./Elle eut le prix tout de même.” (The third says nothing; she got the prize all the same.) Freud concluded that the third sister represented death, and that men chose her in order to give themselves the illusion that death was a matter of choice, thus “making friends with the necessity of dying.”

The man who chooses Pearl Winship is a minister from Massachusetts named Will Severn, who arrives in town to take over Brooklyn’s Congregational church. Severn represents the gentler version of Calvinism that spread through American churches during the first half of the nineteenth century in revulsion against Puritan tenets such as infant damnation. Severn preaches a gospel of love, entreating his flock to love their enemies. “More people make shipwreck on this passage of Scripture than on any other,” he tells them. “The whole shore along here is thick with wrecks.” We are presumably meant to recognize in Severn’s intimacy with Pearl a version of the Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale’s illicit love for Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter, which results in another uncanny Pearl.

In her portrayal of Severn, Barton may also be thinking of the Brooklyn minister Henry Ward Beecher, who preached his own gospel of love (or “gospel of gush,” according to his enemies) before being accused of adultery with one of his parishioners in a well-publicized trial of 1875. As Beecher’s reputation collapsed, the Brooklyn Bridge—its tower on the Brooklyn side nearly finished as the trial was going forward—took the place of Beecher’s Plymouth Church as a source of local pride. As David McCullough writes, “The plain, barnlike church, never much of an architectural beauty, had been replaced by the immense Gothic bridge.”2 It is another strength of Brookland that these literary and historical echoes are never obtrusive.

The central theme of the novel is Prudence Winship’s determination to build a bridge. Barton constructs the narrative in such a way that we are party to Prue’s “dark-minded” thoughts throughout the book. She is fifty when the novel begins, in January of 1822. Her own daughter, Recompense, from whom she is estranged and who is expecting a child of her own, has asked her for the story of the bridge, which has haunted her own unhappy childhood. Barton may have been tempted to tell the story entirely in letters, as with so many eighteenth-century novels, but she uses instead a hybrid form: part letters from Prue and part third-person narration strictly limited to her point of view, with periodic reminders that in such passages we are reading paraphrases of her letters. We are thus spared long stretches of awkward pastiche—only some parts have period-specific punctuation and archaic spelling such as “metaphorickal” and “unremark’d”—while at the same time feeling transported to an earlier time and place.

Advertisement

The idea of the bridge comes to dominate Prue’s imagination in young adulthood after three deaths in quick succession leave her in charge of the distillery and her destiny. The first of the deaths is that of an aging slave named Johanna who runs the Winship household. An intimacy has developed between the brittle Johanna and Prue’s lonely mother; after Johanna dies, Roxana descends into a deep depression and slowly starves herself to death. Matthias’s body is found soon after in the mill-race that powers the distillery; Prue is convinced that her father deliberately leapt from the retaining wall, plunging to his death.

It is in part as a monument to her father that Prue decides to build a bridge. She grew up during the American Revolution, when “Death was everywhere”; British corpses buried in Brooklyn soil give a special flavor to the locally grown asparagus. Even as a child Prue, with her “natively dark imagination,” has had the fantasy that Manhattan represents the “Other Side,” a world of the dead to which shades are conveyed on a “spirit ferry”:

I came to believe the Isle of Mannahata was, in fact, the City of the Dead. Once I had chanced upon this notion,—which another might have tossed out, but which I, made nervous by the sights & sounds of the war & by my mother’s weird rules governing my ingress and egress, determined could be nothing but the dark truth the world strove to hide from children,—everything I saw across the water added to New-York’s sepulchral mystery. All those goods that travelled thither were offerings to appease the shades.

The design of the bridge comes to Prue—as the prompting for a new harness came to Yves Gundron—in a dream: two cantilevered springboards extending from each shore and meeting above the middle of the river. But another image in the dream, Pearl with her tongue cut out and her hair in a “blazing mandorla of fire,” is a disturbing premonition that any success in the building of the bridge will bring suffering to Pearl.

3.

In a book like Brookland, in which carefully researched details form the background of Prue’s “chimerical” schemes, the antiquarian and the visionary must find balance. Emily Barton trusts the reader to take an interest in the minutiae of fermentation, condensation, and distillation, as Prue learns the “hot, noisy, fragrant, and complicated” art of making gin. Equally arcane are the details of engineering in designing the great bridge. Barton relies on a sequence of striking images to carry Prue’s ambition forward. Early on there is a sepia-tinged evocation of the frozen-over East River, when children and adults from both sides of the river venture out onto the “ice bridge”—“bumpy, dull gray, and dirty with ash, twigs, trapped fish, and bits of the week’s papers.”

Particularly poignant is the moment when Pearl shows Prue her drawing of the bridge at 1/250th its final dimensions, like some vast panorama by Frederic Church or a monumental Chinese landscape painting:

They bent over the scroll like reapers, untied the ribbon, and began to pull the ends apart. They had gone no more than a foot when the unfurling image stopped Prue still. There was a schooner tacking into the wind, with her sails as round and full as life and her sailors pulling on her halyards. The water through which the ship plowed was murky and rough…. High above arched the most delicate part of the bridge…. The bridge continued to soar across its great arc, unfurling until it was half as wide as the broad side of the room.

Such visionary moments, resembling Joyce’s “epiphanies,” provide satisfying points of arrival and reflection in the novel. The only slight sag in the narrative occurs as invention and design yield to the more mundane requirements of raising funds and political support for the bridge.

As the novel progresses Prue’s ambition verges on monomania. She mortgages the distillery and her house to forward the plan; she is jealous of any credit accorded anyone else, including her husband and sisters; she seems all but oblivious to the suffering and risk to others incurred by her relentless intentions. Barton’s epigraph, from the eighteenth-century haiku master Yosa Buson in Robert Hass’s translation, hints at the devil’s bargain she seems to have made:

Chrysanthemum growers—

You are the slaves

of chrysanthemums!

At times, Barton implies that success at any art requires some sacrifice; at others we feel that Prue’s willingness to build her bridge at any cost resembles Ahab’s obsession with the white whale or the mania of Hawthorne’s black-veiled minister. When it turns out that the plans for the bridge are faulty, relations between Prue and her loyal husband, who has overseen construction of the foundation, grow cool: “He was as sweet with me as ever,” Prue remarks, “but it was as if I wore a black veil when I spoke with him.”

Prue’s attitude toward her slaves is another blind spot in this conflicted heroine. A slaveholder who knows she cannot run the distillery “at profit entirely on paid labor,” Prue takes pride in the humane treatment of her slaves but never considers freeing them. It is clear from Craig Wilder’s history of race relations in Brooklyn that Prue’s attitudes toward slavery are typical of her generation: “White Brooklynites’ way of life and their ambitions tied them to…African bondage,” Wilder notes. “Over time Brooklyn earned a reputation as a major commercial and industrial city, but its path to wealth tied it to slavery for the rest of that institution’s history in the United States.”3 The gradual and staggered policy of manumission adopted by New York State played out until 1827.4 Like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s much earlier The Minister’s Wooing, Brookland is a salutary reminder that slaves were an essential part of the growth and prosperity of cities in the Northeast well into the nineteenth century.

4.

Emily Barton has written of her admiration for George Eliot’s novels, especially the “long, discursive chapters” of The Mill on the Floss, in which, as in Brookland, “a difficult protagonist… ultimately loses the fight.” The reader may long to give advice to Maggie Tulliver and Prudence Winship, to warn them to choose a more suitable mate or to settle for less in their chaotic lives. But as I finished reading Brookland, it was Willa Cather who came most insistently to mind—Cather whose first novel, Alexander’s Bridge, is also about a heroic designer with outsized ambitions whose flaws are projected onto his great bridge. In several of her subsequent novels, Cather addresses another of Barton’s themes, the human cost of success for a woman artist. Cather’s The Song of the Lark charts the strange emptying out of the successful artist’s personal life as the imaginative life comes to dominate her existence. “Her artistic life,” as Cather observed, “is the only one in which she is happy, or free, or even very real.” This is Prue’s fate as well, so difficult for her sisters and daughter to fathom.

But what of the bridge itself? Emily Barton is hardly the first writer to give central significance to a bridge, or to suggest that bridges link the living and the dead. In T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, “A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,/I had not thought death had undone so many.” The crossing of the East River has inspired two poetic masterpieces, Walt Whitman’s magnificent “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” (published in its first version in 1856) and Hart Crane’s The Bridge (1930).

What is notable about these poems for Barton’s purposes is the way each poet internalizes the bridge, making it an allegory of emotional and spiritual transitions or “crossings.” In “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” Whitman writes of those “dark patches” of the soul, so similar to Prudence Winship’s “dark-mindedness.”

It is not upon you alone the dark patches fall,

The dark threw its patches down upon me also,

The best I had done seem’d to me blank and suspicious,

My great thoughts as I supposed them, were they not in reality meagre?

Nor is it you alone who know what it is to be evil,

I am he who knew what it was to be evil,

I too knitted the old knot of contrariety….

Whitman, who grew up in Brooklyn and often took the ferry across the river, appears as a character in Hart Crane’s sequence inspired by the Brooklyn Bridge. Crane was fascinated by the German-born engineer John Roebling, the friend and student of Hegel who didn’t live to see the completion of his long-imagined project of spanning the East River. Crane lived in Roebling’s former lodgings in Brooklyn as he composed the lines of his own epic about Roebling’s structure of stone and steel. But Crane considered Whitman the true poet of the machine age. It was Whitman who, in Crane’s view, had discerned “New verities, new inklings in the velvet hummed/Of dynamos,” and whose vision of humanity linked by “that span of consciousness…/The Open Road” had summoned the great bridge into reality:

Our Meistersinger, thou set breath in steel;

And it was thou who on the boldest heel

Stood up and flung the span on even wing

Of that great Bridge, Our Myth, whereof I sing!

In her first two novels, Emily Barton has taken on for herself Crane’s self-appointed task to “absorb the machine, i.e., acclimatize it as naturally and casually as trees, cattle, galleons, castles, and all other human associations of the past.” But something else is at work in Barton’s finely tuned vision, it seems to me, though I raise it with some hesitation since it is nowhere explicit in Brookland. I mean the events of September 11, 2001, and their aftermath, coinciding with the period during which Barton, living in Brooklyn, wrote Brookland. The Brooklyn Bridge itself was rumored to be on the list of potential al-Qaeda targets, with Osama bin Laden reportedly threatening to bring down “the bridge in the Godzilla movie.”5 Barton appears to be alluding obliquely to the attacks of September 11 in her references to the “twin towers” of Prudence Winship’s bridge, in her attention to the “retaining wall” of her father’s distillery, which is also the site of his death, and in her notion of the bridge as a monument to the dead. Whatever we make of these apparent allusions, Emily Barton has written a moving testimonial to the dead on both sides of the river.

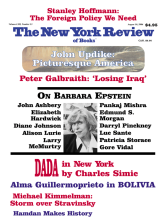

This Issue

August 10, 2006

-

1

Henry R. Stiles, A History of the City of Brooklyn, Vol. 1 (1867), pp. 383–384, quoted in Alan Trachtenberg, Brooklyn Bridge: Fact and Symbol(University of Chicago Press, revised edition, 1979), p. 23. David McCullough, writing in The Great Bridge(Simon and Schuster, 1972), also assumes that Thomas Pope proposed the bridge in 1800 (p. 24).

↩ -

2

McCullough, The Great Bridge, pp. 327–328.

↩ -

3

Craig Steven Wilder, A Covenant with Color: Race and Social Power in Brooklyn (Columbia University Press, 2000), pp. 44–45.

↩ -

4

Wilder, A Covenant with Color, p. 19. Wilder notes that “In 1830, three years after emancipation was to have been completed, 75 black people remained enslaved in New York State.” By 1840, the number had been reduced to four, and another law was passed in 1841 to end slavery in the state.

↩ -

5

David Rennie, “Plot to Destroy Brooklyn Bridge,” Telegraph (UK), June 20, 2003.

↩