Of all the Arab nations created out of the ruins of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, the Emirate of Transjordan was the most ill-favored. A barren splinter of land tapering south to the Red Sea, its borders made no political or geographical sense. It was home to just 230,000 people, and had a single railway line and scarcely a road. Crucially, in later years—1948–1949, 1967—it would be drowned in waves of Palestinian refugees. Plagued by water scarcity, it had few industrial resources and no oil.

This roughcast nation was created by the British in a spirit of mixed expediency and guilt. In 1916 the Hashemite Sha-rif Hussein of Mecca, titular guardian of Arabia’s holy places, instigated the Great Arab Revolt against the Turks, with the fragile understanding that the British had promised him rule over a postwar Arab Middle East. Instead, the liberated lands were parceled up between the colonial powers, first in secret in the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement between Britain and France, and then at the 1919 Paris peace conference. The embittered sharif remained king of the Arabian Hijaz (which he was to lose to Saudi rivals in 1924, when it became Saudi Arabia), while the British assumed control of Iraq and Palestine, and the French of Syria and Lebanon. Soon afterward, the sharif’s third son, Faisal, was handed Iraq as a consolation prize for losing Syria; and by a stroke of the pen, Churchill, then colonial secretary, accorded the sharif’s second son, the ambitious Abdullah, the makeshift Transjordan Emirate under British mandate—but (as the foreign secretary, Lord Curzon, commented) he was “much too big a cock for so small a dunghill.”

Abdullah was the grandfather, mentor, and model of the young King Hussein. As a Hashemite and descendant of the Prophet, Abdullah conceived his ancestral destiny as leader of the Arab peoples. With the outbreak of the Arab–Jewish war in 1948, he moved his British-trained Arab Legion into the Palestinian heartland, and the ensuing peace left him in control of territory a few miles from the Mediterranean, with the prize of East Jerusalem. So together with Israel—and perhaps in tacit collusion—Abdullah aborted Palestinian hopes for a state; and it was a Palestinian nationalist who shot him dead in 1951 outside the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem before the horrified eyes of his grandson. Hussein himself only survived the assassin’s second bullet because it ricocheted off the medal (for school fencing) that his grandfather had insisted he wear.

The enlarged but fragile kingdom became Hussein’s patrimony a year later, when his mentally ill father abdicated. Hussein was crowned king at the age of seventeen, and soon found himself on the political tightrope that he was to tread until his death forty-six years later. Few gave the boy-king long to reign, or even to live. A monarch in a republican age, legitimized by a British Empire that was fading, he found himself governing a country half of whose inhabitants were hostile Palestinians, surrounded by volatile Arab states and a newly forceful Israel. The cold war loomed in the background, and his treasury was empty. His entire reign was spent in crisis, domestic or foreign. He survived countless assassination attempts, from the machine-gunning of his motorcade by fedayeen in 1970 (twice) to the poisoning of his medicine and food—but the would-be assassin first practiced on the palace cats, whose deaths betrayed him.

Three English-language biographies of the King were published before his death,1 but none was as full or as deeply researched as the two under review (and neither book cites them much). Both the present works, inevitably, are more political than personal studies. Virtually the King’s whole life was spent in foreign affairs, and his story becomes the story of the Middle East over half a century.

Avi Shlaim’s Lion of Jordan: The Life of King Hussein in War and Peace is the fuller and more passionately engaged. Shlaim, a professor of international relations at Oxford, is prominent among the so-called “new historians,” Israeli scholars who have radically reassessed Zionist history and the foundation of Israel. Together with Benny Morris and Ilan Pappé (whose political views have now drastically diverged), he has critically analyzed the founding myths of Israel, sometimes using declassified Israeli documents. Lion of Jordan follows on from Shlaim’s Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and the Partition of Palestine, published in 1988. Alongside extensive interviews with Jordanian, Israeli, and Western officials, he is the first to have full access to the papers of Dr. Yaacov Herzog, the high Israeli government official most intimately involved in Hussein’s first, secret contacts with the Israelis.

Shlaim writes in frustration that Jordan has “no proper national archive.” But Nigel Ashton, senior lecturer in international history at the London School of Economics and Political Science, was granted unique access in 2007 to its nearest equivalent, the Royal Hashemite Archives in Amman, which contains the King’s private correspondence. His King Hussein of Jordan: A Political Life, while less expansive than Shlaim’s book, is a scrupulously balanced and finely documented account, buttressed by his own (smaller) range of interviews and new archival research.

Advertisement

Both historians, of course, must negotiate a minefield of complex and still politically charged issues. Jordan’s modern history is entwined with that not only of Israel, but of the often opaque doings of its Arab neighbors (whose archives are closed) and of Britain and the United States. The leitmotif of both books is the tortuous and unflagging peacemaking efforts, both official and secret, of King Hussein with Israel. But these are interspersed with wars and internal crises enough to break the will of a less high-spirited man.

Early in his reign, Hussein, pilloried by the Arabs as a colonial lackey (he had been educated at Harrow and Sandhurst), divested himself of overt British tutelage and sacked General John Bagot Glubb, the commander of his Arab Legion, with uncharacteristic brutality. That same year the still naive King almost pitched himself against Israel during the Suez crisis. Thereafter, with the British connection severed, his need for financial and military security was continuous. He dabbled with liberal democracy but ended by staging a royal coup against his “leftist” prime minister, Suleiman Nabulsi, and faced down mutinous officers in his own army.

The appointment and dismissal of governments became a regular tactic of his paternalist autocracy. In 1958, when his cousin King Faisal of Iraq was bloodily overthrown, he shored up his faltering reign—now the last Hashemite kingdom—with the help of British arms: a bitter humiliation in Arab eyes. Then came the disastrous June 1967 war, in which Jordan lost the West Bank to Israel and received a flood of 200,000 refugees.

How was it, Shlaim asks rhetorically, that in the aftermath of this debacle Jordan attained such diplomatic stature? The answer, he writes,

largely lies in the personality and policies of King Hussein. He was a strong, energetic and charismatic leader who commanded the attention of the great powers by sheer persistence and force of personality. Hussein’s unique brand of personal diplomacy enabled Jordan to exert an influence in foreign affairs that was out of all proportion to its real power. Hussein was the only Arab ruler who had intimate relations with America and relations of any kind at all with Israel, the greatest taboo in Arab politics.

The conviction of his Hashemite destiny, together with some vital natural optimism, carried Hussein through over thirty years’ more trials: through war against his own bitter Palestinian subjects in 1970; the precarious balancing act of the 1973 October war (in which he committed an armored brigade to support Syria); the Camp David conference in which Egypt made a separate peace with Israel; the rise of the Palestine Liberation Organization; and the 1991 Gulf War in which the King notoriously backed Saddam Hussein.2

After the outbreak of the first intifada in 1987 and the upsurge of Palestinian resistance within the occupied territories, Hussein started to disengage from the West Bank, relinquishing representation of the Palestinian people to the PLO. Six years later, in 1993, Israel and the PLO signed a peace accord in Oslo, and the following autumn Jordan and Israel concluded their own treaty. This secured Hussein’s kingdom from extremists on either side eager to convert Jordan into an alternative Palestinian homeland, and it opened the way—Hussein believed—to a more trusting future. For the King, it was the zenith of his career, a “warm peace” realized in friendship with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

Then everything crumbled. Rabin was assassinated by a right-wing zealot at a peace rally in Tel Aviv, making way for the hard-line Benjamin Netanyahu, and the hoped-for West Bank accord faded away as Hussein’s own health declined. He died in 1999 in a hospital bed in Amman, aged sixty-three, with his fourth wife beside him. But his legacy, however fragile, was a workable Jordanian state, less harsh than its neighbors, whose people—almost half Palestinian—were to prove enterprising and flexible in a growing economy.

On the political context of this extraordinary life, Avi Shlaim claims that it is the historian’s duty not only to record but to evaluate. He has said elsewhere: “My view is that the historian is a judge, and above all a hanging judge.”3 In Lion of Jordan, he throws down his challenge at the outset:

My own view is that the Balfour Declaration [the 1917 British statement favoring a Jewish home in Palestine] was one of the worst mistakes in British foreign policy in the first half of the twentieth century. It involved a monumental injustice to the Palestine Arabs and sowed the seeds of a never-ending conflict in the Middle East.

Whether this pronouncement is seen as admirably candid or needlessly provocative, the next seven hundred–odd pages are a powerful, richly researched history, buttressed by a wide range of invaluable interviews. It makes for compulsive but somber reading. Shlaim’s access to the papers of Yaacov Herzog (he calls them “a real treasure trove”) inaugurates a fascinating narrative of the King’s (or his adviser Zaid Rifa’i’s) secret meetings with Israeli officials, including Golda Meir, Yigal Allon, Moshe Dayan, Abba Eban, Shimon Peres, Yitzhak Rabin, and Yitzhak Shamir. He describes fifty-five such meetings in all (and there were probably more). They took place in the privacy of a Jewish doctor’s house in London, or on a ship in the Aqaba Bay, or in the solitude of the Araba desert south of the Dead Sea. For Hussein they were a safety valve and a wishful avenue of hope.

Advertisement

The initial meetings have been documented previously (in Michael Bar- Zohar’s biography of Herzog) but not in this nuanced and human detail. Some of these conclaves were bafflingly insubstantial. But later, after the loss of the West Bank in 1967, the repeated failure to trade land for peace in accordance with UN Resolution 242, the cornerstone of most negotiations, they became grimly predictable. The PLO, of course, was its own worst enemy, and often, in Shlaim’s delicate phrasing, “put doctrinal purity above practical progress.” But for Shlaim the greater burden of blame falls elsewhere:

By its actions Israel revealed that it preferred land to peace with its neighbors. Soon after the end of the 1967 war it began to build settlements in the occupied territories. Building civilian settlements on occupied territory was not just illegal under international law but a major obstacle to peace.

And again, the “allegation of Israeli territorial expansionism and diplomatic intransigence after the war is fully supported by the Israeli documentary record.”

Shlaim held seventy-six interviews with Jordanian officials alone, most importantly with General Ali Shukri, director of Hussein’s private office from 1976; his Israeli interviewees include Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin. All these flesh out his history more than they alter its substance, but there are revelations too, especially concerning the King’s alliance with Saddam Hussein (he visited Baghdad more than sixty times). After a secret meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir just before the 1991 Gulf War, Hussein was even able to pass on to Saddam a barely veiled Israeli threat of nuclear retaliation if Iraq fired chemical warheads into Israel. (They were never fired.) It emerges too that after the King’s treaty with Israel there was a well-developed Syrian plot to assassinate him.

Shlaim’s interviews included an intense, two-hour meeting with the King. His portrait of Hussein is more intimate, affectionate, and engaged than Nigel Ashton’s in King Hussein of Jordan, but he is not blind to Hussein’s faults. The King could be naive and fatally impulsive: danger fired and concentrated his mind. He had no head for paperwork or economics (unlike his brother Prince Hassan) and was indulgent of corruption, including his own. Shlaim goes so far as to attribute to him “a deplorable neglect of internal affairs and especially the welfare of his people.” He was a poor judge of character (although Ashton says he wasn’t). As a young man he was brutal over the divorce of his first wife and in the dismissal of the long-serving General Glubb; and his final days were marred by his treatment of the loyal Prince Hassan, who had been widely seen as his likely heir but was passed over in favor of the King’s oldest son, Abdullah.

But in general, Shlaim writes, Hussein was acknowledged to be courageous, sincere, and remarkably humane:

My sympathy with him as a person was enhanced by the discovery that his efforts to work out a peaceful solution to the conflict in the Middle East met, for the most part, with ignorance and indifference on the part of the top American policy-makers and dishonesty and deviousness on the part of the Israeli ones.

Whereas Shlaim’s blow-by-blow account of Hussein’s career reads as a somberly addictive saga, Nigel Ashton’s King Hussein of Jordan: A Political Life is cooler, more measured, and more concise, even at four hundred–plus pages. It is a very lucid and careful work. Ashton, like Shlaim, makes use of precisely targeted personal interviews, including some that remain anonymous (although, curiously, he omits Prince Hassan). In particular those with Awn al-Khasawneh—Jordan’s leading lawyer at the 1991 Madrid conference that inaugurated a (false) negotiating dawn—are telling about the delicacy of Jordan’s situation.

Ashton’s crucial contribution, however—besides his innate fairness—is the sudden and unfettered access he gained to the hitherto closed Royal Hashemite Archives, whose disclosures obliged him virtually to rewrite his book. Hussein’s papers, which grew ampler in the later years of his reign, include correspondence not only with leading Arab and some Israeli figures, but with every contemporary American president and British prime minister. There is even an exchange with Mikhail Gorbachev.

The many letters of interest or importance include those from presidents Sadat and Carter around the time of the Camp David summit, where Egypt made its unilateral peace; the airily fulsome handwritten missives of Saddam Hussein, whom the King so unwisely supported; correspondence with George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton; and above all the revealing exchanges between a disillusioned Hussein and a blustering Reagan on the 1986 Iran–contra scandal. Reagan’s understanding of the Middle Eastern quagmire was so limited that in private he seems hastily to have agreed with Hussein about almost everything. At a 1981 meeting, according to the future king, Prince Abdullah,

the King had spent thirty minutes alone with the president, who had come out agreeing with much of what he had said. Reagan’s staff had had to back-pedal hastily and thereafter he was never allowed to spend any time alone with Hussein.

More light-heartedly, Reagan attempted small talk by inquiring about the quality of fishing in the (fatally saline) Dead Sea, and whether to introduce Californian fish into it. He even pursued this unpromising topic by letter. It was typical of Hussein’s good manners that he drew the line so delicately under the absurdity:

Mr. President, a while ago I received your message pertaining to the subject of the possibility of introducing fish into the Dead Sea. I was most touched by your thoughtfulness in this regard which prompted your investigating the possibility. We had, in any event, reconciled ourselves to the fact that the Dead Sea is dead….

As with Shlaim, Ashton’s new material fleshes out and finesses history rather than drastically altering it, but it lends Ashton’s work a judicious precision and authority. There are passages in which his judgments diverge from those of Shlaim, but they are not many. Shlaim imagines that at one point Saddam Hussein might have withdrawn voluntarily after invading Kuwait; Ashton, more convincingly, thinks not. And Ashton treats less enthusiastically the Jordanian–Israeli peace treaty, which Shlaim—empathizing with Hussein—hails as the pinnacle of the King’s reign.

More remarkable is the overall concurrence between these two historians of such different temperaments. Ashton too finds that

the covert dialogue with Hussein after 1967 seems to have been pursued from the Israeli side more as an extension of domestic political rivalries, and as a holding operation, than as a serious peace process.

And both men see Hussein’s proud Hashemite heritage as crucial to his cast of mind and sense of destiny. This was ingrained very early, through the influence of his powerful mother, Zain al-Sharaf, and of his revered grandfather Abdullah, and underlay Hussein’s mission to achieve peace not only for Hashemite Jordan but for the wider Arab world.

It is here that a nagging question arises that is never quite confronted: How far did the King’s Hashemite allegiance, even in his own mind, conflict with his dedication to Arab (and especially Palestinian) peace? There is no ready answer. But Shlaim and Ashton agree broadly on the periods of optimism that arose, although each gives them a subtly different emphasis, Shlaim warmer and more engaged, Ashton more circumspect. Of these, the so-called London Agreement in 1987 between Hussein and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres raised momentary hope, but was doomed by Israeli domestic division. Then came the Madrid conference of 1991, at which the Palestinians—“long the missing party, at the Middle East conference table”—were at last represented in their own right. Finally the extraordinary friendship that flowered between Hussein and Yitzhak Rabin lit its own beacon of reconciliation. Rabin, writes Ashton,

was a unique figure among Israeli prime ministers: the one man who had arrived at a complete and thorough-going conviction that it was time to make a historic compromise between Zionism and Arab nationalism. This was what made him so dangerous a figure for extremists on both sides.

If Rabin’s assassination was, in a sense, the unluckiest event of Hussein’s career, there were others more of his own making. The King’s reluctant assent to the establishment of the PLO in 1964, under pressure from Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, spelled the eventual end of the fantasy of Jordan and Palestine as one country, and opened a new door to violence.

Perhaps this would have happened anyway; but the King’s loss of the West Bank to Israel in 1967 was the result of serious misjudgments. As the Arab nations slid into war with Israel under popular pressure and their own rivalries, Hussein impulsively signed a defense treaty with Nasser that placed his Arab Legion under Egyptian command and allowed foreign Arab armies into Jordan. On the opening day of the war Israel sent messages warning the King not to act; but they were ignored. Later Hussein was to say that he either had to enter the war or see his country—with half its population Palestinian—torn apart by civil war. Shlaim doubts the inevitability of this slide into the abyss, while Ashton accepts it. But the West Bank, they agree, was lost militarily, not through Israeli greed, but through Arab internal politics and disarray.

What is missing from both of these distinguished biographies is any evocation, or rounded portrait, of the King himself. There is little even of the personal quirks and details that are often so eloquent. The authors are political historians, after all, and Hussein’s character becomes relevant chiefly as the (frustrated) engine of his politics. Shlaim’s work evolved from a political monograph, and Ashton aptly subtitles his book A Political Life.

Ashton, however, mentions that when the British Foreign Office drew up social “topics of conversation” before one of the King’s state visits, it included waterskiing, motorboats, skin-diving, aircraft, and youth culture. Hussein never quite shed his playboy image. Outdoor life became a passion, and perhaps a release. He loved piloting his own plane (to the horror of Henry Kissinger). The eruption of the October 1973 war found him riding his motorbike with Queen Alia behind him (a similar image—but now with Queen Noor behind him—adorns the back of Ashton’s book).

Hussein was not a long-term strategist, still less an intellectual. He worked by intuition. It was his boyish and emotional nature, perhaps, that made him vulnerable to such larger-than-life figures as Nasser and Saddam Hussein. But of his courage (and impetuousness) there can be no doubt. The British, with condescending affection, dubbed him the PLK, the Plucky Little King. The tragedies in his reign plunged him into nervous despondency, but never quite into despair.

Hussein’s youthful autobiography Uneasy Lies the Head (1962) suggests a man more lonely and vulnerable than either Ashton or Shlaim intimates. His confidence evolved slowly, piecemeal. The astute Dr. Herzog, on his first meeting with the twenty-eight-year-old monarch, wrote:

I was struck by the apparent contradictions in his posture—maturity with leadership, levity with dignity, escapism with responsibility. The almost crushing burden of perilous leadership seemed to have caught his youth unaware.

These, perhaps, were the twin personalities that enabled Hussein to engage in tough realpolitik while preserving his youth’s idealism, and to neglect the internal affairs and material well-being of his country yet remain notably compassionate. “Forgiving and co-opting opponents,” says Shlaim, “became an enduring part of Jordan’s political culture.”

But for the King’s living presence we must turn to the inimitable James Morris, who witnessed Hussein announce the overthrow and murder of his beloved cousin Faisal of Iraq in 1958:

He walked into the conference room of his palace closely surrounded by officers, officials, policemen, security guards, walking quickly and tensely to the head of the table. His face was lined and tired, and moisture glistened in the corners of his eyes…. “I have now had confirmation,” he said slowly, “of the murder of my cousin, brother, and childhood playmate, King Feisal of Iraq, and all his royal family.” He paused, his eyes filling, his lip trembling, a muscle working rhythmically in the side of his jaw, and then he said it again, in identical words, but with a voice that was awkwardly thickening…. And raising his head from his notes, Hussein added in his strange formal English: “They are only the last in a caravan of martyrs.”4

The moderate Jordanian politician Marwan Muasher receives honorable mention in Shlaim’s book as the first Jordanian ambassador to Israel after the 1994 treaty. His The Arab Center: The Promise of Moderation is in part a political memoir, in part an agenda for a solution to today’s eight-year stagnation of the Arab–Israeli peace process.

Muasher was the Jordanian spokesman at the Madrid conference. While ambassador in Washington he was an intimate witness to the closing months of Hussein’s reign, and gives a moving, firsthand account of how the dying King saved an agreement that edged the peace process forward. His narrative of this, and of the royal succession crisis, has its own historical value.

Thereafter, his account of the Jordanian maneuvers for peace have all the gloomy ring of déjà vu. The Saudi-sponsored Arab Peace Initiative that he fostered in 2002—a rare show of collective Arab action—foundered in Palestinian–Israeli violence. Now, six years later, with the road map at a dead end and the Israeli separation wall gone up—affecting the lives (he reckons) of more than 200,000 Palestinians—Muasher makes a strenuous call for US reinvestment in the peace process. Already blueprints are in place, he feels (the Arab and Geneva Peace Initiatives or the Clinton parameters proposed in 2000) and time is running out.

Two familiar factors lend urgency to his plea. One is the retreat of secular Arab nationalism before the advance of radical Islam, which threatens not only Israel but what Muasher calls the Arab Center—the internationally moderate core of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. The second is the demographic Palestinian time bomb: the forecast that within the area of historical Palestine (Israel, the West Bank, Gaza) the number of Arabs will exceed that of Jews within a generation.

Muasher’s principled but pragmatic voice is not that of the historian but rather of a crusading diplomat. His book is endorsed by his own king, Abdullah II of Jordan, and by President Clinton. In its resilience there is an echo of the old king, Hussein. But Muasher is a Jordanian Christian, not a Hashemite patriarch, and he argues, inter alia, for Arab governments to reform their systems in the interests of civil society and international partnership. As for peace with Israel, he suggests that the US, the UN, the European Union, and Russia together present a two-state solution, based on the most moderate previous initiatives, give the parties a limited time to work out the details, and then quickly conduct a plebiscite on a permanent settlement. He writes:

Any return to a gradual political process is, in my opinion, futile. Many forces against peace stand ready to derail the process if given the chance. Time has revealed their determination and capabilities.

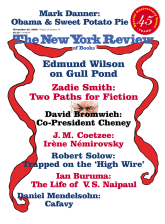

This Issue

November 20, 2008

The Co-President at Work

At Gull Pond

Two Paths for the Novel

-

1

Peter John Snow, Hussein: A Biography (Barrie and Jenkins, 1972); James Lunt, Hussein of Jordan: Searching for a Just and Lasting Peace (William Morrow, 1989); Roland Dallas, King Hussein: A Life on the Edge (London: Profile, 1998).

↩ -

2

Shlaim recalls, however, that during the 1980–1988 Iran–Iraq war, “America and Britain used Hussein and his generals to arm Saddam Hussein covertly.” Jordan, he writes, “was the perfect front for covert American operations, whether they involved intelligence sharing or the supply of arms.” The CIA station in Amman “played a part in promoting these clandestine shipments to Baghdad.”

↩ -

3

Interview with Elliott Colla in Middle East Report, May 10, 2002.

↩ -

4

James Morris, The Hashemite Kings (Pantheon, 1959).

↩