I had a dream: Israeli Arab students, enraged by the war in Gaza, were protesting at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. A counterdemonstration by Jewish students erupted. When the head of university security, a Holocaust survivor, tried to intervene, the Arab students called him a Nazi.

Actually, I didn’t dream this. Shlomo Avineri, a political scientist at the university, related the incident, which occurred in the first days after Israel began its Gaza war on December 27. But dreams cut to the quick. There’s no point denying that a line of sorts runs from the forty-three people killed by Israeli fire near a United Nations school in Gaza on January 6 back to the Palestinian Nakba (catastrophe) of 1948 and to Berlin, 1945.

History is relentless. Sometimes its destructive gyre gets overcome: France and Germany freed themselves after 1945 from war’s cycle. So, even more remarkably, did Poland and Germany. China and Japan scarcely love each other but do business. Only in the Middle East do the dead rule. As Yehuda Amichai, the Israeli poet, once observed, the dead vote in Jerusalem. Their demand for blood is, it seems, inexhaustible. Their graves will not be quieted. Since 1948 and Israel’s creation, retribution has reigned between the Jewish and Palestinian national movements.

I have never previously felt so despondent about Israel, so shamed by its actions, so despairing of any peace that might terminate the dominion of the dead in favor of opportunity for the living.

More than dreams, I’ve been having nightmares. I cannot see a scenario in which any short-term Israeli tactical victory over Hamas is not overwhelmed by the long-term strategic cost of this war. Khaled Meshal, the political director of Hamas in Damascus, declared fifteen days into the war that it had “destroyed the last chance for negotiations.” A little over a year after the Bush administration’s much-heralded Annapolis conference, a Mideast peace has never seemed more distant. On Israel–Palestine, as much else, the outgoing president’s capacity to exit in flames is conspicuous.

But before I get to that, let me return, for a moment, to those protesting Israeli Arab students. There are about 1.3 million Arab citizens of Israel, or a little less than 20 percent of the population. Their loyalties are divided, but never before have they protested so vigorously. That’s a fair guide to the virulence of Arab sentiment, stoked by graphic around-the-clock coverage of the Gaza carnage from the al-Jazeera and al-Arabiya networks. President Bashar al-Assad of Syria, resorting to the same loaded World War II lexicon, has called Gaza “a concentration camp,” a term also recently used by Cardinal Renato Martino, the head of the Vatican Council for Justice and Peace.

These jackboot allusions—which include Meshal’s reference to a Gaza “holocaust”—are untenable: a Jewish minority in any Arab state of the size of the Arab minority in Israel is unimaginable. Israel remains a small island of relatively liberal democracy in a repressive Arab sea. But it is ghettoizing itself, not least from the agonizing plight of the estimated 1.5 million Palestinians crammed into the narrow strip of land that is Gaza.

The high-tech security fence built to wall off the West Bank and the near-hermetic sealing of Gaza since the Israeli withdrawal in 2005 are in the end attempts to shut out reality. Palestinians have become a vague abstraction to most Israelis not within the range of Hamas rockets: out of sight, out of mind. Israel, shamefully, has even prevented international journalists from getting into Gaza to tell the story as they see it. Long before a six-month cease-fire crumbled in mid-December (a little over a month after the November 4 Israeli military raid into Gaza that killed six Hamas militants), Israel had also cut delivery of critical supplies of food, medicine, fuel, fertilizer, cash, and spare parts to a trickle. Gaza bakeries were idled, banks closed, salaries unpaid. A society where unemployment routinely runs at almost 50 percent was in a state of breakdown.

But what do Blackberrying Israelis on their six-lane, wall-flanked highways know of that? In this context the hallucinogenic appeals of the government of caretaker prime minister Ehud Olmert to ordinary Palestinians in Gaza, asking them to realize that Hamas is their common enemy, become more understandable. Mark Regev, Olmert’s spokesman, has accused Hamas of “holding hostage” these Palestinians. Under aerial and tank bombardment from an alien power, with more than one thousand dead (about 40 percent of them women and children) and several thousand wounded, that’s not how most people would view their democratically elected government.

Tzipi Livni, the foreign minister, who despises Olmert, has meanwhile talked about changing “the equation” in Gaza. The only changed equation I see over time is more entrenched hatred for Israel in Gaza: those myriad dead and wounded have relatives, some of whom may one day strap on suicide belts.

Advertisement

As for Ehud Barak, the third of the sound-bite-mouthing Israeli troika and leader of the Labor Party, his talk as defense minister of deepening and broadening the Gaza campaign has not been unrelated to an attempt to deepen and broaden his appeal among Israelis who see him as a peacenik. His poll numbers have been rising. The subtext of political maneuvering ahead of the February 10 elections, in which Livni as leader of the centrist Kadima party is also a candidate for prime minister, has been one of the more repellent aspects of the Gaza war. Benjamin Netanyahu, the conservative Likud leader who is still ahead in polls, has been conspicuously silent: the murkier the outcome in Gaza, it seems, the more he would tend to benefit.

The heroic Israeli narrative has run its course.

But what of the intolerable Hamas Qassam rockets on the Israeli city Sderot, the fourteen Israelis killed by those rockets since 2005 (four of them in the current violence), the vile annihilationist language of the Hamas Charter? Yes, there has to be a response to Hamas, but this is the wrong one.

It’s been wrong since James Wolfensohn, the former World Bank president, saw his attempts to get economic activity going in Gaza in 2005 thwarted by border closure and “everything getting wasted.” After a year in that job, marginalized, Wolfensohn slipped away. He told me that “the view on the American and Israeli side was that you could not trust the Palestinians, and the result was not to build more economic activity, but to build more barriers. And I personally did not think that was the way forward.” Consistent with this bridge-breaking approach was the ostracism, from Israel and the United States, which followed the Hamas victory in the free and fair January 2006 elections for the Legislative Council of the Palestinian Authority.

Israel has the right to hit back at Hamas when attacked—but not to blow Gaza to pieces, or deprive people of food, water, and medicine. In at least one appalling incident at Zeitoun, on the east of Gaza City, where children were found next to their mothers’ days-old corpses, the International Red Cross has accused Israel of an “unacceptable” failure “to meet its obligation under international law to care for and evacuate the wounded.” Israel denies targeting civilians, accuses Hamas of using civilians as human shields, and says it works in “close cooperation” with international aid organizations. But at some point—and I would say a couple of hundred dead children in Gaza are already well past that point—such denials become pointless: the facts speak for themselves. No invocation of collateral damage or legitimate defense can excuse such wanton killing. As Avi Shlaim, a professor of international relations and former soldier in the Israeli army, has observed, the Gaza offensive “seems to follow the logic of an eye for an eyelash.”

There is another right that Israel does not have: to delude its people into thinking that peace is achievable without coming to terms with the deeply entrenched Middle Eastern realities that are Hamas and Hezbollah, organizations still viewed in the US government and Congress almost exclusively through the prism of terror, but whose grassroots political movements present a far more complex, variegated picture. The logic of the Israeli offensive, if there is one, must surely be that Hamas can be so weakened as ultimately to crumble. That is also the logic of the relentless blockade that persisted during the six-month cease-fire despite Israel’s earlier commitment, as part of the deal, to opening border crossings. But such logic is flawed. Hamas is not going away. As Brigadier General (Res.) Shmuel Zakai, the former commander of the Israel Defense Forces’ Gaza Division, told Ha’aretz on December 22:

We could have eased the siege over the Gaza Strip, in such a way that the Palestinians, Hamas, would understand that holding their fire served their interests. But when you create a tahadiyeh [truce], and the economic pressure on the Strip continues, it’s obvious that Hamas will try to reach an improved tahadiyeh, and that their way to achieve this is resumed Qassam fire.

Israel, backed by the United States, has been intent on proving that Hamas must wither and die rather than exploring ways in which it, like the Palestine Liberation Organization before it, can move toward being part of a two-state solution. That is a strategic mistake. Hamas, even with perhaps three hundred of its leaders and militants killed, has been strengthened as a political and social movement by Olmert’s last fling, the reckless foray of a failed leader.

Advertisement

I had another dream: that Israeli Arabs, in need of work and cash, were building bomb shelters for Jews in Sderot. Like the first, it proved to be true. Money still talks in the Middle East. Alas, the dead talk louder.

—January 15, 2009

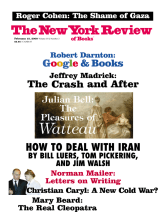

This Issue

February 12, 2009