In response to:

The Torch of Karl Kraus from the October 23, 2008 issue

To the Editors:

Concerning Adam Kirsch’s “The Torch of Karl Kraus” [NYR, October 23, 2008]: Richard Wagner’s famous essay “Jewishness in Music” does not contain the remark that Heinrich Heine “lied his way to the status of poet.” On the contrary: Wagner repeatedly praised Heine—who had inspired him to compose his opera The Flying Dutchman—for his extraordinary poetic gifts and for his intellectual and artistic integrity in castigating “all the illusions of self-deception,” particularly among his fellow Jews. Indeed, Wagner’s description of Heine reminds one of Kraus himself. Wagner also had a few kind words for another Jew, Ludwig Boerne, whose conversion had been more sincere than that of Heine.

Henry Wassermann

Professor, Department of History,

Philosophy and Jewish Studies

The Open University of Israel

Raanana, Israel

Adam Kirsch replies:

I am baffled by Henry Wassermann’s complaisant reading of Wagner’s famous anti-Semitic essay, “Judaism in Music.” Paul Reitter is quite correct when he writes in The Anti-Journalist that, according to Wagner, Heine “lied his way to the status of poet” ( sich zum Dichter log )—or, as William Ashton Ellis, the nineteenth-century translator of Wagner’s prose works, rendered it, “duped himself into a poet.” Wagner goes on to refer to Heine’s poems as “versified lies” ( gedichteten Lügen ).

And the praise for Heine’s “intellectual and artistic integrity” to which Professor Wassermann alludes is the most left-handed of compliments, as a glance at the essay makes clear. “At the time when Goethe and Schiller sang among us, we certainly know nothing of a poetizing Jew,” Wagner writes; “at the time, however, when our poetry became a lie, when every possible thing might flourish from the wholly unpoetic element of our life, but no true poet”—at that moment, Heine emerged as “a highly-gifted poet-Jew.” In other words, Heine was the poet of the age because the age was inartistic and inauthentic —“Judaized,” in Wagner’s sense of the word.

For Professor Wassermann to speak of Wagner’s “kind words” for Ludwig Boerne is still more incomprehensible to me, for what Wagner meant to praise was precisely Boerne’s self-hatred; Wagner commended him for realizing that “to become Man…means firstly for the Jew as much as ceasing to be Jew.” If “Wagner’s description of Heine reminds one of Kraus himself,” it is only because Kraus was infected by the very anti-Semitic clichés that Wagner helped release into the bloodstream of German culture. This is, indeed, one of the major theses of Paul Reitter’s book.

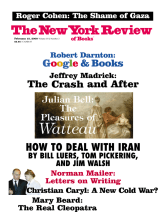

This Issue

February 12, 2009