The following is based on a lecture given at the New York Public Library in December 2008.

1.

Hello. This voice I speak with these days, this English voice with its rounded vowels and consonants in more or less the right place—this is not the voice of my childhood. I picked it up in college, along with the unabridged Clarissa and a taste for port. Maybe this fact is only what it seems to be—a case of bald social climbing—but at the time I genuinely thought this was the voice of lettered people, and that if I didn’t have the voice of lettered people I would never truly be lettered. A braver person, perhaps, would have stood firm, teaching her peers a useful lesson by example: not all lettered people need be of the same class, nor speak identically. I went the other way. Partly out of cowardice and a constitutional eagerness to please, but also because I didn’t quite see it as a straight swap, of this voice for that.

My own childhood had been the story of this and that combined, of the synthesis of disparate things. It never occurred to me that I was leaving the London district of Willesden for Cambridge. I thought I was adding Cambridge to Willesden, this new way of talking to that old way. Adding a new kind of knowledge to a different kind I already had. And for a while, that’s how it was: at home, during the holidays, I spoke with my old voice, and in the old voice seemed to feel and speak things that I couldn’t express in college, and vice versa. I felt a sort of wonder at the flexibility of the thing. Like being alive twice.

But flexibility is something that requires work if it is to be maintained. Recently my double voice has deserted me for a single one, reflecting the smaller world into which my work has led me. Willesden was a big, colorful, working-class sea; Cambridge was a smaller, posher pond, and almost univocal; the literary world is a puddle. This voice I picked up along the way is no longer an exotic garment I put on like a college gown whenever I choose—now it is my only voice, whether I want it or not. I regret it; I should have kept both voices alive in my mouth. They were both a part of me. But how the culture warns against it! As George Bernard Shaw delicately put it in his preface to the play Pygmalion, “many thousands of [British] men and women…have sloughed off their native dialects and acquired a new tongue.”

Few, though, will admit to it. Voice adaptation is still the original British sin. Monitoring and exposing such citizens is a national pastime, as popular as sex scandals and libel cases. If you lean toward the Atlantic with your high-rising terminals you’re a sell-out; if you pronounce borrowed European words in their original style—even if you try something as innocent as parmigiano for “parmesan”—you’re a fraud. If you go (metaphorically speaking) down the British class scale, you’ve gone from Cockney to “mockney,” and can expect a public tar and feathering; to go the other way is to perform an unforgivable act of class betrayal. Voices are meant to be unchanging and singular. There’s no quicker way to insult an ex-pat Scotsman in London than to tell him he’s lost his accent. We feel that our voices are who we are, and that to have more than one, or to use different versions of a voice for different occasions, represents, at best, a Janus-faced duplicity, and at worst, the loss of our very souls.

Whoever changes their voice takes on, in Britain, a queerly tragic dimension. They have betrayed that puzzling dictum “To thine own self be true,” so often quoted approvingly as if it represented the wisdom of Shakespeare rather than the hot air of Polonius. ” What’s to become of me? What’s to become of me?” wails Eliza Doolittle, realizing her middling dilemma. With a voice too posh for the flower girls and yet too redolent of the gutter for the ladies in Mrs. Higgins’s drawing room.

But Eliza—patron saint of the tragically double-voiced—is worthy of closer inspection. The first thing to note is that both Eliza and Pygmalion are entirely didactic, as Shaw meant them to be. “I delight,” he wrote,

in throwing [Pygmalion] at the heads of the wiseacres who repeat the parrot cry that art should never be didactic. It goes to prove my contention that art should never be anything else.

He was determined to tell the unambiguous tale of a girl who changes her voice and loses her self. And so she arrives like this:

Advertisement

Don’t you be so saucy. You ain’t heard what I come for yet. Did you tell him I come in a taxi?… Oh, we are proud! He ain’t above giving lessons, not him: I heard him say so. Well, I ain’t come here to ask for any compliment; and if my moneys not good enough I can go elsewhere…. Now you know, don’t you? I’m come to have lessons, I am. And to pay for em too: make no mistake…. I want to be a lady in a flower shop stead of selling at the corner of Tottenham Court Road. But they wont take me unless I can talk more genteel.

And she leaves like this:

I can’t. I could have done it once; but now I can’t go back to it. Last night, when I was wandering about, a girl spoke to me; and I tried to get back into the old way with her; but it was no use. You told me, you know, that when a child is brought to a foreign country, it picks up the language in a few weeks, and forgets its own. Well, I am a child in your country. I have forgotten my own language, and can speak nothing but yours.

By the end of his experiment, Professor Higgins has made his Eliza an awkward, in-between thing, neither flower girl nor lady, with one voice lost and another gained, at the steep price of everything she was, and everything she knows. Almost as afterthought, he sends Eliza’s father, Alfred Doolittle, to his doom, too, securing a three-thousand-a-year living for the man on the condition that Doolittle lecture for the Wannafeller Moral Reform World League up to six times a year. This burden brings the philosophical dustman into the close, unwanted embrace of what he disdainfully calls “middle class morality.” By the time the curtain goes down, both Doolittles find themselves stuck in the middle, which is, to Shaw, a comi-tragic place to be, with the emphasis on the tragic. What are they fit for? What will become of them?

How persistent this horror of the middling spot is, this dread of the interim place! It extends through the specter of the tragic mulatto, to the plight of the transsexual, to our present anxiety —disguised as genteel concern—for the contemporary immigrant, tragically split, we are sure, between worlds, ideas, cultures, voices—whatever will become of them? Something’s got to give—one voice must be sacrificed for the other. What is double must be made singular.

But this, the apparent didactic moral of Eliza’s story, is undercut by the fact of the play itself, which is an orchestra of many voices, simultaneously and perfectly rendered, with no shade of color or tone sacrificed. Higgins’s Harley Street high-handedness is the equal of Mrs. Pierce’s lower-middle-class gentility, Pickering’s kindhearted aristocratic imprecision every bit as convincing as Arthur Doolittle’s Nietzschean Cockney-by-way-of-Wales. Shaw had a wonderful ear, able to reproduce almost as many quirks of the English language as Shakespeare’s. Shaw was in possession of a gift he wouldn’t, or couldn’t, give Eliza: he spoke in tongues.

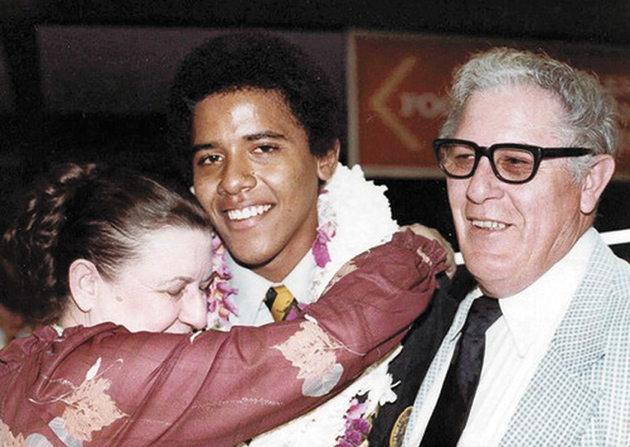

It gives me a strange sensation to turn from Shaw’s melancholy Pygmalion story to another, infinitely more hopeful version, written by the new president of the United States of America. Of course, his ear isn’t half bad either. In Dreams from My Father, the new president displays an enviable facility for dialogue, and puts it to good use, animating a cast every bit as various as the one James Baldwin—an obvious influence—conjured for his own many-voiced novel Another Country. Obama can do young Jewish male, black old lady from the South Side, white woman from Kansas, Kenyan elders, white Harvard nerds, black Columbia nerds, activist women, churchmen, security guards, bank tellers, and even a British man called Mr. Wilkerson, who on a starry night on safari says credibly British things like: “I believe that’s the Milky Way.” This new president doesn’t just speak for his people. He can speak them. It is a disorienting talent in a president; we’re so unused to it. I have to pinch myself to remember who wrote the following well-observed scene, seemingly plucked from a comic novel:

“Man, I’m not going to any more of these bullshit Punahou parties.”

“Yeah, that’s what you said the last time….”

“I mean it this time…. These girls are A-1, USDA-certified racists. All of ’em. White girls. Asian girls—shoot, these Asians worse than the whites. Think we got a disease or something.”

“Maybe they’re looking at that big butt of yours. Man, I thought you were in training.”

“Get your hands out of my fries. You ain’t my bitch, nigger…buy your own damn fries. Now what was I talking about?”

“Just ’cause a girl don’t go out with you doesn’t make her a racist.”

This is the voice of Obama at seventeen, as remembered by Obama. He’s still recognizably Obama; he already seeks to unpack and complicate apparently obvious things (“Just ’cause a girl don’t go out with you doesn’t make her a racist”); he’s already gently cynical about the impassioned dogma of other people (“Yeah, that’s what you said the last time”). And he has a sense of humor (“Maybe they’re looking at that big butt of yours”). Only the voice is different: he has made almost as large a leap as Eliza Doolittle. The conclusions Obama draws from his own Pygmalion experience, however, are subtler than Shaw’s. The tale he tells is not the old tragedy of gaining a new, false voice at the expense of a true one. The tale he tells is all about addition. His is the story of a genuinely many-voiced man. If it has a moral it is that each man must be true to his selves, plural.

Advertisement

For Obama, having more than one voice in your ear is not a burden, or not solely a burden—it is also a gift. And the gift is of an interesting kind, not well served by that dull publishing-house title Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance with its suggestion of a simple linear inheritance, of paternal dreams and aspirations passed down to a son, and fulfilled. Dreams from My Father would have been a fine title for John McCain’s book Faith of My Fathers, which concerns exactly this kind of linear masculine inheritance, in his case from soldier to soldier. For Obama’s book, though, it’s wrong, lopsided. He corrects its misperception early on, in the first chapter, while discussing the failure of his parents’ relationship, characterized by their only son as the end of a dream. “Even as that spell was broken,” he writes, “and the worlds that they thought they’d left behind reclaimed each of them, I occupied the place where their dreams had been.”

To occupy a dream, to exist in a dreamed space (conjured by both father and mother), is surely a quite different thing from simply inheriting a dream. It’s more interesting. What did Pauline Kael call Cary Grant? ” The Man from Dream City.” When Bristolian Archibald Leach became suave Cary Grant, the transformation happened in his voice, which he subjected to a strange, indefinable manipulation, resulting in that heavenly sui generis accent, neither west country nor posh, American nor English. It came from nowhere, he came from nowhere. Grant seemed the product of a collective dream, dreamed up by moviegoers in hard times, as it sometimes feels voters have dreamed up Obama in hard times. Both men have a strange reflective quality, typical of the self-created man—we see in them whatever we want to see. ” Everyone wants to be Cary Grant,” said Cary Grant. ” Even I want to be Cary Grant.” It’s not hard to imagine Obama having that same thought, backstage at Grant Park, hearing his own name chanted by the hopeful multitude. Everyone wants to be Barack Obama. Even I want to be Barack Obama.

2.

But I haven’t described Dream City. I’ll try to. It is a place of many voices, where the unified singular self is an illusion. Naturally, Obama was born there. So was I. When your personal multiplicity is printed on your face, in an almost too obviously thematic manner, in your DNA, in your hair and in the neither this nor that beige of your skin—well, anyone can see you come from Dream City. In Dream City everything is doubled, everything is various. You have no choice but to cross borders and speak in tongues. That’s how you get from your mother to your father, from talking to one set of folks who think you’re not black enough to another who figure you insufficiently white. It’s the kind of town where the wise man says “I” cautiously, because “I” feels like too straight and singular a phoneme to represent the true multiplicity of his experience. Instead, citizens of Dream City prefer to use the collective pronoun “we.”

Throughout his campaign Obama was careful always to say we. He was noticeably wary of “I.” By speaking so, he wasn’t simply avoiding a singularity he didn’t feel, he was also drawing us in with him. He had the audacity to suggest that, even if you can’t see it stamped on their faces, most people come from Dream City, too. Most of us have complicated back stories, messy histories, multiple narratives.

It was a high-wire strategy, for Obama, this invocation of our collective human messiness. His enemies latched on to its imprecision, emphasizing the exotic, un-American nature of Dream City, this ill-defined place where you could be from Hawaii and Kenya, Kansas and Indonesia all at the same time, where you could jive talk like a street hustler and orate like a senator. What kind of a crazy place is that? But they underestimated how many people come from Dream City, how many Americans, in their daily lives, conjure contrasting voices and seek a synthesis between disparate things. Turns out, Dream City wasn’t so strange to them.

Or did they never actually see it? We now know that Obama spoke of Main Street in Iowa and of sweet potato pie in Northwest Philly, and it could be argued that he succeeded because he so rarely misspoke, carefully tailoring his intonations to suit the sensibility of his listeners. Sometimes he did this within one speech, within one line: “We worship an awesome God in the blue states, and we don’t like federal agents poking around our libraries in the red states.” Awesome God comes to you straight from the pews of a Georgia church; poking around feels more at home at a kitchen table in South Bend, Indiana. The balance was perfect, cunningly counterpoised and never accidental. It’s only now that it’s over that we see him let his guard down a little, on 60 Minutes, say, dropping in that culturally, casually black construction “Hey, I’m not stupid, man, that’s why I’m president,” something it’s hard to imagine him doing even three weeks earlier. To a certain kind of mind, it must have looked like the mask had slipped for a moment.

Which brings us to the single-voiced Obamanation crowd. They rage on in the blogs and on the radio, waiting obsessively for the mask to slip. They have a great fear of what they see as Obama’s doubling ways. “He says one thing but he means another”—this is the essence of the fear campaign. He says he’s a capitalist, but he’ll spread your wealth. He says he’s a Christian, but really he’s going to empower the Muslims. And so on and so forth. These are fears that have their roots in an anxiety about voice. Who is he? people kept asking. I mean, who is this guy, really? He says sweet potato pie in Philly and Main Street in Iowa! When he talks to us, he sure sounds like us—but behind our backs he says we’re clinging to our religion, to our guns. And when Jesse Jackson heard that Obama had lectured a black church congregation about the epidemic of absent black fathers, he experienced this, too, as a tonal betrayal; Obama was “talking down to black people.” In both cases, there was the sense of a double-dealer, of someone who tailors his speech to fit the audience, who is not of the people (because he is able to look at them objectively) but always above them.

The Jackson gaffe, with its Oedipal violence (“I want to cut his nuts out”), is especially poignant because it goes to the heart of a generational conflict in the black community, concerning what we will say in public and what we say in private. For it has been a point of honor, among the civil rights generation, that any criticism or negative analysis of our community, expressed, as they often are by white politicians, without context, without real empathy or understanding, should not be repeated by a black politician when the white community is listening, even if ( especially if) the criticism happens to be true (more than half of all black American children live in single-parent households). Our business is our business. Keep it in the family; don’t wash your dirty linen in public; stay unified. (Of course, with his overheard gaffe, Jackson unwittingly broke his own rule.)

Until Obama, black politicians had always adhered to these unwritten rules. In this way, they defended themselves against those two bogeymen of black political life: the Uncle Tom and the House Nigger. The black politician who played up to, or even simply echoed, white fears, desires, and hopes for the black community was in danger of earning these epithets—even Martin Luther King was not free from such suspicions. Then came Obama, and the new world he had supposedly ushered in, the postracial world, in which what mattered most was not blind racial allegiance but factual truth. It was felt that Jesse Jackson was sadly out of step with this new postracial world: even his own son felt moved to publicly repudiate his “ugly rhetoric.” But Jackson’s anger was not incomprehensible nor his distrust unreasonable. Jackson lived through a bitter struggle, and bitter struggles deform their participants in subtle, complicated ways. The idea that one should speak one’s cultural allegiance first and the truth second (and that this is a sign of authenticity) is precisely such a deformation.

Right up to the wire, Obama made many black men and women of Jackson’s generation suspicious. How can the man who passes between culturally black and white voices with such flexibility, with such ease, be an honest man? How will the man from Dream City keep it real? Why won’t he speak with a clear and unified voice? These were genuine questions for people born in real cities at a time when those cities were implacably divided, when the black movement had to yell with a clear and unified voice, or risk not being heard at all. And then he won. Watching Jesse Jackson in tears in Grant Park, pressed up against the varicolored American public, it seemed like he, at least, had received the answer he needed: only a many-voiced man could have spoken to that many people.

A clear and unified voice. In that context, this business of being biracial, of being half black and half white, is awkward. In his memoir, Obama takes care to ridicule a certain black girl called Joyce—a composite figure from his college days who happens also to be part Italian and part French and part Native American and is inordinately fond of mentioning these facts, and who likes to say:

I’m not black…I’m multiracial…. Why should I have to choose between them?… It’s not white people who are making me choose…. No—it’s black people who always have to make everything racial. They’re the ones making me choose. They’re the ones who are telling me I can’t be who I am….

He has her voice down pat and so condemns her out of her own mouth. For she’s the third bogeyman of black life, the tragic mulatto, who secretly wishes she “passed,” always keen to let you know about her white heritage. It’s the fear of being mistaken for Joyce that has always ensured that I ignore the box marked “biracial” and tick the box marked “black” on any questionnaire I fill out, and call myself unequivocally a black writer and roll my eyes at anyone who insists that Obama is not the first black president but the first biracial one. But I also know in my heart that it’s an equivocation; I know that Obama has a double consciousness, is black and, at the same time, white, as I am, unless we are suggesting that one side of a person’s genetics and cultural heritage cancels out or trumps the other.

But to mention the double is to suggest shame at the singular. Joyce insists on her varied heritage because she fears and is ashamed of the singular black. I suppose it’s possible that subconsciously I am also a tragic mulatto, torn between pride and shame. In my conscious life, though, I cannot honestly say I feel proud to be white and ashamed to be black or proud to be black and ashamed to be white. I find it impossible to experience either pride or shame over accidents of genetics in which I had no active part. I understand how those words got into the racial discourse, but I can’t sign up to them. I’m not proud to be female either. I am not even proud to be human—I only love to be so. As I love to be female and I love to be black, and I love that I had a white father.

It’s telling that Joyce is one of the few voices in Dreams from My Father that is truly left out in the cold, outside of the expansive sympathy of Obama’s narrative. She is an entirely didactic being, a demon Obama has to raise up, if only for a page, so everyone can watch him slay her. I know the feeling. When I was in college I felt I’d rather run away with the Black Panthers than be associated with the Joyces I occasionally met. It’s the Joyces of this world who “talk down to black folks.” And so to avoid being Joyce, or being seen to be Joyce, you unify, you speak with one voice.

And the concept of a unified black voice is a potent one. It has filtered down, these past forty years, into the black community at all levels, settling itself in that impossible injunction “keep it real,” the original intention of which was unification. We were going to unify the concept of Blackness in order to strengthen it. Instead we confined and restricted it. To me, the instruction “keep it real” is a sort of prison cell, two feet by five. The fact is, it’s too narrow. I just can’t live comfortably in there. ” Keep it real” replaced the blessed and solid genetic fact of Blackness with a flimsy imperative. It made Blackness a quality each individual black person was constantly in danger of losing. And almost anything could trigger the loss of one’s Blackness: attending certain universities, an impressive variety of jobs, a fondness for opera, a white girlfriend, an interest in golf. And of course, any change in the voice. There was a popular school of thought that maintained the voice was at the very heart of the thing; fail to keep it real there and you’d never see your Blackness again.

How absurd that all seems now. And not because we live in a postracial world—we don’t—but because the reality of race has diversified. Black reality has diversified. It’s black people who talk like me, and black people who talk like L’il Wayne. It’s black conservatives and black liberals, black sportsmen and black lawyers, black computer technicians and black ballet dancers and black truck drivers and black presidents. We’re all black, and we all love to be black, and we all sing from our own hymn sheet. We’re all surely black people, but we may be finally approaching a point of human history where you can’t talk up or down to us anymore, but only to us. He’s talking down to white people —how curious it sounds the other way round! In order to say such a thing one would have to think collectively of white people, as a people of one mind who speak with one voice—a thought experiment in which we have no practice. But it’s worth trying. It’s only when you play the record backward that you hear the secret message.

3.

For reasons that are obscure to me, those qualities we cherish in our artists we condemn in our politicians. In our artists we look for the many-colored voice, the multiple sensibility. The apogee of this is, of course, Shakespeare: even more than for his wordplay we cherish him for his lack of allegiance. Our Shakespeare sees always both sides of a thing, he is black and white, male and female—he is everyman. The giant lacunae in his biography are merely a convenience; if any new facts of religious or political affiliation were ever to arise we would dismiss them in our hearts anyway. Was he, for example, a man of Rome or not? He has appeared, to generations of readers, not of one religion but of both, in truth, beyond both. Born into the middle of Britain’s fierce Catholic–Protestant culture war, how could the bloody absurdity of those years not impress upon him a strong sense of cultural contingency?

It was a war of ideas that began for Will—as it began for Barack—in the dreams of his father. For we know that John Shakespeare, a civic officer in Protestant times, oversaw the repainting of medieval frescoes and the destruction of the rood loft and altar in Stratford’s own fine Guild Chapel, but we also know that in the rafters of the Shakespeare home John hid a secret Catholic “Spiritual Testament,” a signed profession of allegiance to the old faith. A strange experience, to watch one’s own father thus divided, professing one thing in public while practicing another in private. John Shakespeare was a kind of equivocator: it’s what you do when you’re in a corner, when you can’t be a Catholic and a loyal Englishman at the same time. When you can’t be both black and white. Sometimes in a country ripped apart by dogma, those who wish to keep their heads—in both senses—must learn to split themselves in two.

And this we still know, here, at a four-hundred-year distance. No one can hope to be president of these United States without professing a committed and straightforward belief in two things: the existence of God and the principle of American exceptionalism. But how many of them equivocated, and who, in their shoes, would not equivocate, too?

Fortunately, Shakespeare was an artist and so had an outlet his father didn’t have—the many-voiced theater. Shakespeare’s art, the very medium of it, allowed him to do what civic officers and politicians can’t seem to: speak simultaneous truths. (Is it not, for example, experientially true that one can both believe and not believe in God?) In his plays he is woman, man, black, white, believer, heretic, Catholic, Protestant, Jew, Muslim. He grew up in an atmosphere of equivocation, but he lived in freedom. And he offers us freedom: to pin him down to a single identity would be an obvious diminishment, both for Shakespeare and for us. Generations of critics have insisted on this irreducible multiplicity, though they have each expressed it different ways, through the glass of their times. Here is Keats’s famous attempt, in 1817, to give this quality a name:

At once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.

And here is Stephen Greenblatt doing the same, in 2004:

There are many forms of heroism in Shakespeare, but ideological heroism—the fierce, self-immolating embrace of an idea or institution—is not one of them.

For Keats, Shakespeare’s many voices are quasi-mystical as suited the Romantic thrust of Keats’s age. For Greenblatt, Shakespeare’s negative capability is sociopolitical at root. Will had seen too many wild-eyed martyrs, too many executed terrorists, too many wars on the Catholic terror. He had watched men rage absurdly at rood screens and write treatises in praise of tables. He had seen men disemboweled while still alive, their entrails burned before their eyes, and all for the preference of a Latin Mass over a common prayer or vice versa. He understood what fierce, singular certainty creates and what it destroys. In response, he made himself a diffuse, uncertain thing, a mass of contradictory, irresolvable voices that speak truth plurally. Through the glass of 2009, “negative capability” looks like the perfect antidote to “ideological heroism.”

From our politicians, though, we still look for ideological heroism, despite everything. We consider pragmatists to be weak. We call men of balance naive fools. In England, we once had an insulting name for such people: trimmers. In the mid-1600s, a trimmer was any politician who attempted to straddle the reviled middle ground between Cavalier and Roundhead, Parliament and the Crown; to call a man a trimmer was to accuse him of being insufficiently committed to an ideology. But in telling us of these times, the nineteenth-century English historian Thomas Macaulay draws our attention to Halifax, great statesman of the Privy Council, set up to mediate between Parliament and Crown as London burned. Halifax proudly called himself a trimmer, assuming it, Macaulay explains, as

a title of honour, and vindicat[ing], with great vivacity, the dignity of the appellation. Everything good, he said, trims between extremes. The temperate zone trims between the climate in which men are roasted and the climate in which they are frozen. The English Church trims between the Anabaptist madness and the Papist lethargy. The English constitution trims between the Turkish despotism and Polish anarchy. Virtue is nothing but a just temper between propensities any one of which, if indulged to excess, becomes vice.

Which all sounds eminently reasonable and Aristotelian. And Macaulay’s description of Halifax’s character is equally attractive:

His intellect was fertile, subtle, and capacious. His polished, luminous, and animated eloquence…was the delight of the House of Lords…. His political tracts well deserve to be studied for their literary merit.

In fact, Halifax is familiar—he sounds like the man from Dream City. This makes Macaulay’s caveat the more striking:

Yet he was less successful in politics than many who enjoyed smaller advantages. Indeed, those intellectual peculiarities which make his writings valuable frequently impeded him in the contests of active life. For he always saw passing events, not in the point of view in which they commonly appear to one who bears a part in them, but in the point of view in which, after the lapse of many years, they appear to the philosophic historian.

To me, this is a doleful conclusion. It is exactly men with such intellectual peculiarities that I have always hoped to see in politics. But maybe Macaulay is correct: maybe the Halifaxes of this world make, in the end, better writers than politicians. A lot rests on how this president turns out—but that’s a debate for the future. Here I want instead to hazard a little theory, concerning the evolution of a certain type of voice, typified by Halifax, by Shakespeare, and very possibly the President. For the voice of what Macaulay called “the philosophic historian” is, to my mind, a valuable and particular one, and I think someone should make a proper study of it. It’s a voice that develops in a man over time; my little theory sketches four developmental stages.

The first stage in the evolution is contingent and cannot be contrived. In this first stage, the voice, by no fault of its own, finds itself trapped between two poles, two competing belief systems. And so this first stage necessitates the second: the voice learns to be flexible between these two fixed points, even to the point of equivocation. Then the third stage: this native flexibility leads to a sense of being able to “see a thing from both sides.” And then the final stage, which I think of as the mark of a certain kind of genius: the voice relinquishes ownership of itself, develops a creative sense of disassociation in which the claims that are particular to it seem no stronger than anyone else’s. There it is, my little theory—I’d rather call it a story. It is a story about a wonderful voice, occasionally used by citizens, rarely by men of power. Amidst the din of the 2008 culture wars it proved especially hard to hear.

In this lecture I have been seeking to tentatively suggest that the voice that speaks with such freedom, thus unburdened by dogma and personal bias, thus flooded with empathy, might make a good president. It’s only now that I realize that in all this utilitarianism I’ve left joyfulness out of the account, and thus neglected a key constituency of my own people, the poets! Being many-voiced may be a complicated gift for a president, but in poets it is a pure delight in need of neither defense nor explanation. Plato banished them from his uptight and annoying republic so long ago that they have lost all their anxiety. They are fancy-free.

“I am a Hittite in love with a horse,” writes Frank O’Hara.

I don’t know what blood’s

in me I feel like an African prince I am a girl walking downstairs

in a red pleated dress with heels I am a champion taking a fall

I am a jockey with a sprained ass-hole I am the light mist

in which a face appears

and it is another face of blonde I am a baboon eating a banana

I am a dictator looking at his wife I am a doctor eating a child

and the child’s mother smiling I am a Chinaman climbing a mountain

I am a child smelling his father’s underwear I am an Indian

sleeping on a scalp

and my pony is stamping in

the birches,

and I’ve just caught sight of the

Niña, the Pinta and the Santa

Maria.

What land is this, so free?

Frank O’Hara’s republic is of the imagination, of course. It is the only land of perfect freedom. Presidents, as a breed, tend to dismiss this land, thinking it has nothing to teach them. If this new president turns out to be different, then writers will count their blessings, but with or without a president on board, writers should always count their blessings. A line of O’Hara’s reminds us of this. It’s carved on his gravestone. It reads: “Grace to be born and live as variously as possible.”

But to live variously cannot simply be a gift, endowed by an accident of birth; it has to be a continual effort, continually renewed. I felt this with force the night of the election. I was at a lovely New York party, full of lovely people, almost all of whom were white, liberal, highly educated, and celebrating with one happy voice as the states turned blue. Just as they called Iowa my phone rang and a strident German voice said: “Zadie! Come to Harlem! It’s vild here. I’m in za middle of a crazy Reggae bar—it’s so vonderful! Vy not come now!”

I mention he was German only so we don’t run away with the idea that flexibility comes only to the beige, or gay, or otherwise marginalized. Flexibility is a choice, always open to all of us. (He was a writer, however. Make of that what you will.)

But wait: all the way uptown? A crazy reggae bar? For a minute I hesitated, because I was at a lovely party having a lovely time. Or was that it? There was something else. In truth I thought: but I’ll be ludicrous, in my silly dress, with this silly posh English voice, in a crowded bar of black New Yorkers celebrating. It’s amazing how many of our cross-cultural and cross-class encounters are limited not by hate or pride or shame, but by another equally insidious, less-discussed, emotion: embarrassment. A few minutes later, I was in a taxi and heading uptown with my Northern Irish husband and our half-Indian, half-English friend, but that initial hesitation was ominous; the first step on a typical British journey. A hesitation in the face of difference, which leads to caution before difference and ends in fear of it. Before long, the only voice you recognize, the only life you can empathize with, is your own. You will think that a novelist’s screwy leap of logic. Well, it’s my novelist credo and I believe it. I believe that flexibility of voice leads to a flexibility in all things. My audacious hope in Obama is based, I’m afraid, on precisely such flimsy premises.

It’s my audacious hope that a man born and raised between opposing dogmas, between cultures, between voices, could not help but be aware of the extreme contingency of culture. I further audaciously hope that such a man will not mistake the happy accident of his own cultural sensibilities for a set of natural laws, suitable for general application. I even hope that he will find himself in agreement with George Bernard Shaw when he declared, “Patriotism is, fundamentally, a conviction that a particular country is the best in the world because you were born in it.” But that may be an audacious hope too far. We’ll see if Obama’s lifelong vocal flexibility will enable him to say proudly with one voice “I love my country” while saying with another voice “It is a country, like other countries.” I hope so. He seems just the man to demonstrate that between those two voices there exists no contradiction and no equivocation but rather a proper and decent human harmony.

This Issue

February 26, 2009