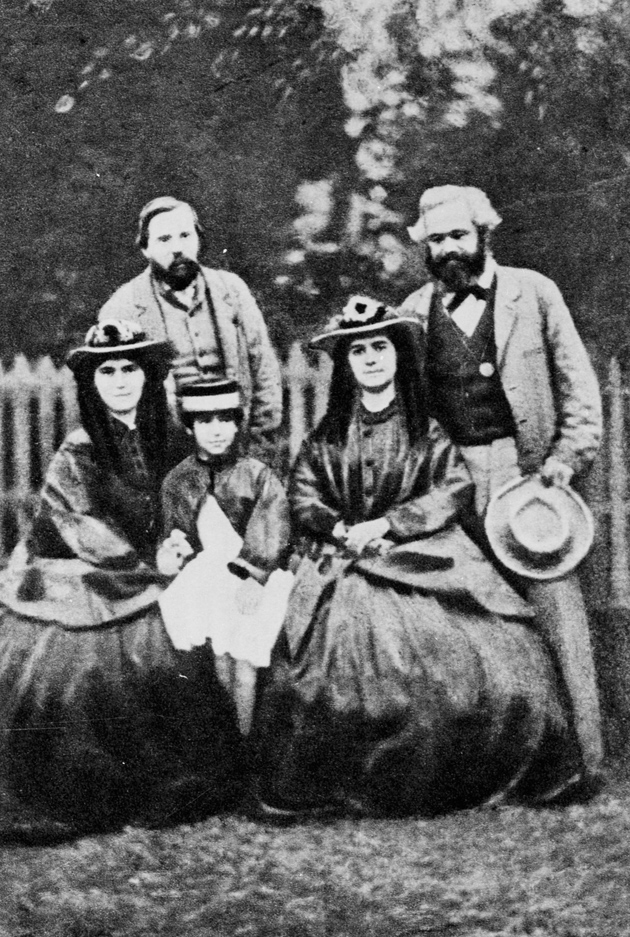

The traffic of pilgrims to the grave of Karl Marx, in London’s Highgate Cemetery, may not be as large as it once was. But at least the grave still exists, presided over by the enormous black bust erected by the British Communist Party in the 1950s, after so many statues of Marx’s heirs have been destroyed. “His name will endure through the ages, and so also will his work,” said Friedrich Engels in a speech at Marx’s funeral, on March 17, 1883; and even if the second part of that prophecy seems doubtful today, the first is surely beyond dispute.

But what about Engels himself? Anyone wishing to visit his resting place will find no place to go. When he died, twelve years after Marx, Engels ordered that his body be cremated and his ashes thrown into the English Channel. It was as if he wanted to make certain that, as Tristram Hunt writes at the end of Marx’s General, “in death as in life there was nothing to detract from the glory of Marx.” Such self-effacement was the constant theme of Engels’s relationship with his best friend, collaborator, and alter ego, from the beginning of their partnership, when they were in their mid-twenties, until its end a lifetime later. “Marx was a genius,” Engels declared, “we others were at best talented.”

Such self-deprecation does not make Engels sound like a very urgent subject for a new biography. The problem is compounded by the fact that, for twenty years, Engels’s primary contribution to the birth of Marxism was to retire from writing and organizing so that he could earn money to support Marx and his family. After 1848, when their activities during the failed German revolution made them personae non grata on the Continent, Marx and Engels moved to England, whose liberalism sheltered them even as they attacked it. Marx’s story during the next two decades is one of great intellectual and human drama. Living in dire poverty in a Soho slum, enduring the deaths of children and his own tormenting illnesses, he gave painful birth to Capital and asserted doctrinal control over the burgeoning Communist movement.

Engels, on the other hand, spent that crucial period working at Ermen and Engels, the family cotton-spinning business in Manchester, sending part of his income to Marx, and living pretty well on what was left over. As Hunt writes, Engels’s existence was that of “a leading Manchester merchant—a sophisticated, high-bourgeois world of dinners, clubs, charitable events, and networking.” It was a double life, not just ideologically but domestically, too. Engels was officially unmarried, and maintained a respectable bachelor apartment for receiving guests, but he was actually living with Mary Burns, a working-class Irishwoman who was effectively his wife. It was a ticklish situation for a man who railed against the sexual exploitation of working women by their employers. “The right of the first night was transferred from the feudal lords to the bourgeois manufacturers,” Engels complained, but his arrangement with Mary—and the way that, after her death, he filled her place with her sister, Lizzy—itself has a rather feudal feel.

That the basis for Engels’s pleasures and Marx’s work was, ultimately, the exploitation of the proletariat—the very thing the two men dedicated their lives to ending—makes Engels’s Manchester years appear not just undramatic but potentially hypocritical. Engels does not sound very indignant, for instance, when writing to Marx about a day he spent with the Cheshire Hunt: “On Saturday I went out fox-hunting—seven hours in the saddle… At least twenty of the chaps fell off or came down, two horses were done for, one fox killed (I was in AT THE DEATH).” Engels’s pleasure in this aristocratic pastime is not fully explained by the fact that it was supposedly good training for the cavalry maneuvers he would be called upon to lead, come the revolution. But he refused to be embarrassed by his inconsistencies. “Would it ever occur to me to apologise for the fact that I myself was once a partner in a firm of manufacturers?” Engels wrote after his retirement. “There’s a fine reception waiting for anyone who tries to throw that in my teeth!”

Engels’s doubleness, which offers such a striking contrast to Marx’s single-mindedness, is why he proves to be a surprisingly fruitful subject for Tristram Hunt. The book’s original title in the UK was The Frock-Coated Communist, and Hunt makes much of the piquancy of the juxtaposition: the revolutionary in a respectable frock coat, the militant who indulged his taste for wine and women. Engels, Hunt suggests, proves that communism is not just a matter of party congresses and five-year plans, or even of Marx’s boils and pawnshops. “Neither a Leveler nor a statist,” Hunt writes,

Advertisement

this great lover of the good life, passionate advocate of individuality, and enthusiastic believer in literature, culture, art, and music as an open forum could never have acceded to the Soviet communism of the twentieth century, all the Stalinist claims of his paternity notwithstanding.

As this shows, part of Hunt’s case in Marx’s General is that Engels should not be held “responsible for the ter- rible misdeeds carried out under the banner of Marxism-Leninism.” And certainly all the crimes of twentieth-century communism seem far away from the gemütlich Sunday afternoons at Engels’s house in London in the 1870s, after he had retired from business:

The house specialty was a springtime bowl of Maitrank, a May wine flavored with woodruff. There would be German folk songs round the piano or Engels reciting his favorite poem, “The Vicar of Bray,” while the cream of European socialism—from Karl Kautsky to William Morris to Wilhelm Liebknecht to Keir Hardie—all paid court.

Such appealing vignettes, Hunt suggests, can help us rehabilitate Marxism from the avenging prophet Marx by casting it in the more amiable image of Engels. In the same vein, Hunt quotes Engels’s responses to “the highly popular mid-Victorian parlor game ‘Confessions,'” asked him by Marx’s daughter Jenny. “Favourite virtue: jollity,” “Idea of happiness: Chateau Margaux 1848,” “Favourite hero: None”—these answers of Engels are charmingly liberal. Hunt could have shown this even more effectively if he had contrasted them with Marx’s own to the same questionnaire, which Francis Wheen gives in full in his 1999 biography Karl Marx: “Favourite virtue: Simplicity,” “Idea of happiness: To fight,” “Favourite hero: Spartacus.”

Yet if there is a gulf separating Marx from Engels, and Engels from Marxism-Leninism, there is also a connection, which Marx’s General makes it possible to trace. For while Engels found more pleasure in life than Marx, he was no less committed to revolutionary struggle. It did not take Marx or Marxism to turn him into a Communist. And the more likable Engels seems as a man, the more terrible his theoretical ruthlessness becomes. It was Engels, not Marx, who wrote that “history is about the most cruel of all goddesses, and she leads her triumphal car over heaps of corpses.”

Friedrich Engels was born on November 28, 1820, the first son and namesake of a prosperous manufacturer in Barmen, in the Rhineland. The Engelses were Pietists, uniting a severe Calvinist discipline with a sharp eye for business. Hunt quotes a letter Engels’s grandfather wrote to his father before he was born, setting out a Max Weberian creed: “We have to look to our own advantage even in spiritual matters.” In such a home, even the most trivial infraction was treated as a soul-endangering sin. When Engels’s father was scandalized by discovering “a dirty book” in the fourteen-year-old’s desk, it was not the kind of book we might think, but merely “a story about knights in the thirteenth century.” This was bad enough for Engels senior to write, “May God watch over his disposition, I am often fearful for this otherwise excellent boy.”

He had reason to be afraid; he was rearing his would-be destroyer. In the 1840s, when Engels was openly preaching communism around Barmen, his father told a friend: “You can’t imagine how much this grieves a father: first my father endowed the Protestant parish in Barmen, then I built a church and now my son is tearing it down.” “That’s the story of our times,” the friend replied. Indeed, Engels’s relationship with what he called “my fanatical and despotic old man” seems to prefigure those of the Kirsanovs in Fathers and Sons or the Verkhovenskys in The Possessed.

The difference is that Engels was too much of a realist—and too devoted to his mother—simply to break with his family, which would have meant condemning himself to a life of poverty. Rather, his revolutionary education took place within the establishment, in tandem with his progress in his bourgeois career. In 1837, Engels left the Gymnasium to begin working in the family firm. The next year he went to Bremen, where he apprenticed as a clerk in a linen-exporting company, while also making his first mild experiments with rebellion. At this stage, Hunt shows, this mainly took the form of growing a mustache, and writing a poem about it: “We are not philistines, so we/Can let our mustachios flourish free.”

Things became more serious when Engels moved to Berlin, where he performed his required year of military service. This was the start of his lifelong interest in military matters, which earned him the nickname “General,” to which Hunt’s title alludes. (Marx was “Moor,” for his dark complexion.) More important, Engels was also attending lectures at the University of Berlin, especially those of Friedrich Schelling, Hegel’s great antagonist. “Ask anybody in Berlin today on what field the battle for dominion over German public opinion is being fought,” Engels wrote, “and if he has any idea of the power of the mind over the world he will reply that this battlefield is the University, in particular Lecture-hall No. 6, where Schelling is giving his lectures in the philosophy of revelation.” As Hunt notes, this was no understatement: in addition to Engels, the audience included Jacob Burckhardt, Mikhail Bakunin, and Søren Kierkegaard.

Advertisement

At the university, Engels made contact with the Young Hegelians and cemented his hostility to the established order in Germany. Earnest as his politics were, they did not make him humorless: he had a dog named Nameless, whom he trained to growl at anyone Engels identified as an aristocrat. In fact, when Engels first met Marx, in 1842, Marx disdained him as a typically frivolous coffeehouse revolutionary. Marx, who was two years older than Engels, had just become editor of the Cologne newspaper Rheinische Zeitung, and hoped to transform it into a forum for serious discussion of communism. He wanted nothing to do with what he called the “rowdiness and blackguardism” of Engels’s Berlin circle, and when Engels visited the paper’s offices, his reception by Marx was “distinctly chilly.”

But Engels was about to prove that he was a much more serious Communist than Marx had thought. From late 1842 until the summer of 1844, Engels lived in Manchester, sent there by his father to learn the intricacies of the international cotton trade; “Manchester Exchange,” he wrote, “is the thermometer which records all the fluctuations of industrial and commercial activity.” But he was also exploring the realities of life among the victims of the industrial revolution, to which his intimacy with Mary Burns gave him unusual access.

Engels was hardly the only writer to engage in what Hunt calls “favella tourism” in Manchester. On the contrary, the city had already become a symbol of the power and the misery of the new industrial order, and everyone who thought seriously about the condition-of-England question had to come to grips with it. Carlyle’s Past and Present, Disraeli’s Sybil, Dickens’s Hard Times, and Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South were among the literary treatments of the subject, and they drew on a host of official reports on the poverty, sickness, ignorance, and despair afflicting the city’s workers.

What set The Condition of the Working Class in England apart from all these books was that Engels’s was not intended to cajole or shame the rich into doing their duty by the poor. Rather, Engels promised while writing it, “I shall be presenting the English with a fine bill of indictment. I accuse the English bourgeoisie before the entire world of murder, robbery and other crimes on a massive scale.” And he was certain that only a violent revolution could put an end to those crimes. “The war of the poor against the rich will be the most bloodthirsty the world has ever seen,” Engels predicted, and no parliamentary legislation or Dickensian sentimentality could avert it. “Even if some of the middle classes espouse the cause of the workers—even if the middle classes as a whole mended their ways—the catastrophe could not be avoided.”

In fact, while most of Engels’s book is devoted to the plight of the working class, its motive force—the animus that makes it such electric reading, even today—is his feelings about his own class, the bourgeoisie. For while Engels gathered the material for the book in Manchester, he actually wrote it in his family home in Barmen, in late 1844. That summer, on the way back from England, he had stopped in Paris and met Marx again. This time, he recalled, “our complete agreement in all theoretical fields became evident,” and their great friendship began. Now, back in his provincial, pious home, the memory of Manchester and the excitement of Paris catalyzed Engels’s overwhelming disgust with his father and his father’s class. As he wrote to Marx in January 1845:

…Barmen is too hideous, the waste of time is too hideous, and what is particularly hideous is to remain not only a bourgeois but actually a factory owner, a bourgeois actively engaged against the proletariat. A few days in my old man’s factory led me once more to realize fully this hideousness which I had begun to overlook…. If I did not have to record in my book each day those ghastly stories from English society I believe I would have begun to get into a rut, but that at least has kept my anger on the boil.

That boiling can be heard in Engels’s repeated insistence that the bourgeoisie is beyond redemption. “The members of the bourgeoisie are imprisoned by the class prejudices and principles which have been ruthlessly drummed into them from childhood. Nothing can be done about people of this sort,” he writes. Indeed, the incorrigibility of the bourgeoisie is central to Engels’s vision of class conflict. It is not a matter of the hard-heartedness of this or that factory owner, or even of all the factory owners; the problem is a capitalist system that is structurally oppressive. That is why only revolution, not reform, can help the proletariat.

It creates an interesting tension in Condition, then, when the reader realizes how consistently Engels’s evidence for the malfeasance of the bourgeoisie is drawn from bourgeois sources. Take this passage, on homelessness and prostitution in London’s parks:

But let all men, whether of theory or of practice, remember this—that within the most courtly precincts of the richest city on GOD’S earth, there may be found, night after night, winter after winter, women—young in years—old in sin and suffering—outcasts from society—ROTTING FROM FAMINE, FILTH AND DISEASE. Let them remember this, and learn not to theorize but to act.

The opposition of theory and practice sounds Marxist; but in fact this call to arms is quoted from an editorial in The Times. Likewise, many of Engels’s lurid details and damning statistics come from official reports like Edwin Chadwick’s Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, which was commissioned by a Whig government and published under a Tory one, in 1842. Indeed, while Engels insists that the workers cannot hope for redress from a bourgeois-aristocratic Parliament, he can’t help but note that “although the middle classes at the moment are the main—indeed the only—power in Parliament, nevertheless the last session (1844) was in effect a continuous debate on working-class conditions.”

All this suggests that far from being obdurate, England’s ruling classes were taking action—slowly and as yet inadequately—to solve the problems caused by the industrial revolution. These problems were, it is useful to remember, totally unprecedented, not just in English but in human history. The sudden eruption of vast polluted slums in the North of England baffled both the institutions of government and the prevailing theories of economics and society. Engels was writing at perhaps the worst period in Manchester’s history, before the introduction of free trade, the expansion of the franchise, unionization, and regulation of factory work and child labor helped to improve the lives of the workers. Yet he insisted that what he witnessed in Manchester were “working class conditions in their ‘classical’ form,” and that things could not get better without getting worse.

The Condition of the Working Classin England was the first expression of Engels’s lifelong belief that revolution was just around the corner. The cycle of boom and bust, he wrote in the book’s conclusion, meant that

the next [economic] crisis should (on the analogy of previous crises) occur in 1852 or 1853…. But before that crisis arrives the English workers will surely have reached the limits of their endurance…. Popular fury will reach an intensity far greater than that which animated the French workers in 1793.

The year 1853 came and went, and Engels postponed the reckoning: “This time there’ll be a day of wrath such as has never been seen before…all the propertied classes in the soup, complete ruin of the bourgeoisie…. I, too, believe that it will all come to pass in 1857,” he wrote to Marx. In 1865, when the American Civil War had cut off cotton exports to England and devastated Manchester, Engels was sanguine again: “I imagine by next month the working people themselves will have had enough of sitting about with a look of passive misery on their faces.”

It is impossible, reading such prophecies, not to be reminded of the disappointed members of some chiliastic cult, constantly recalculating the date of the apocalypse. And here lies the most significant aspect of Engels’s story. There was only one Marx; but there have been many millions of Marxists, and Engels was the first of these. His dilemma was the same one faced by generations of committed revolutionaries since: How should one live in a dying world that is on the verge of transformation?

For Engels, this was an even more difficult problem than it was for, say, the Seventh-Day Adventists (whose prophet, William Miller, initially predicted that 1843 would be the end of days). For, like Marx, Engels inherited from Hegel the paradox that history at once requires and negates the freedom of individual men. In the influential 1878 polemic known as Anti-Dühring, in which Engels offered an accessible restatement of Marxist principles (and, less happily, tried to use the theory of dialectical materialism to explain nature and mathematics), he attempted to heal this paradox by redefining freedom: “Freedom does not consist in the dream of independence of natural laws, but in the knowledge of those laws and in the possibility thus afforded of making them work systematically towards definite ends.” But this only sharpens the dilemma, for what could be more absurd than “working systematically” to implement a natural law, like gravity?

The implications of this question for Engels’s work on behalf of Marx and Marxism were, of course, profound. Engels had nothing but contempt for the idea that socialism could be the gift of an inspired prophet, as the followers of Fourier and Saint-Simon seemed to believe. He was careful to praise Marx not as a lawgiver, but as the discoverer of laws that had always been in operation. “Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of organic nature,” he said in his eulogy, “so Marx discovered the law of development of human history.” Yet the analogy is crucially flawed, for while The Origin of Species did nothing to accelerate or divert the course of evolution, TheCommunist Manifesto was an intervention into the very class conflict it diagnosed. As Engels went on to say:

Marx was before all else a revolutionist. His real mission in life was to contribute, in one way or another, to the overthrow of capitalist society and of the state institutions which it had brought into being, to contribute to the liberation of the modern proletariat.

It was only because Marx was uniquely capable of advancing that cause that Engels willingly devoted his life to him.

To Hunt, as to most writers on the subject, Engels’s decision to spend the prime of his life doing work he disliked in order to support Marx’s labors inspires admiration and pity. “In truth, the middle decades of Engels’s life were a wretched time…an era of nervous, sapping sacrifice,” Hunt writes. Edmund Wilson said the same thing in To the Finland Station, likening Marx and Engels to the positive and negative poles of a battery: “Marx was to play the part of the metal of the positive electrode, which gives out hydrogen and remains unchanged, while Engels was to be the negative electrode, which gradually gets used up.”

Reading Marx’s General, however, makes one wonder whether Engels really was stuck at the negative pole of the partnership. For surely it was Marx who piled up the “misery” and “agony of toil,” at his desk in London, and Engels who enjoyed the “accumulation of wealth.” The difference between them was brought out most starkly in the autumn of 1848, the year of revolutions, when Marx and Engels thought they might actually be seeing their dreams come true. Marx had started a new radical newspaper, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, in Cologne, with Engels and other comrades. After Engels gave a fiery speech to an open-air workers’ meeting, he was threatened with arrest and forced to flee the city, while Marx stayed behind, agitating for democratic revolution even as the reaction gathered force.

But instead of going to Paris, or Venice, or one of the other battlefields of the continent, Engels set out on a long walking tour of the French countryside. He drank wine (“What a diversity, from Bordeaux to Burgundy,…from Petit Macon or Chablis to Chambertin”), slept with country girls, and admired the trees. When he got to Auxerre, he joked that the town looked like a “red republic with all its horrors,” when in fact it was simply streaming with the juice of the wine harvest. This sudden holiday, in the middle of the revolution for which he had been waiting his whole life, led Wilson to remark on the “Jekyll-and-Hyde personality” that Engels displayed: ferocious and acerbic with Marx, amiable and pleasure-loving when on his own.

This was, perhaps, Engels’s solution to the problem of waiting out a dying world. He would not live in the agony of historical expectation, like Marx, but savor the fallen present, deferring the rigors of salvation into the ever-receding future, where other people would have to endure them. Kierkegaard, Engels’s old classmate at the University of Berlin, summarized his objection to Hegel by comparing him to a man who, having constructed a grand palace, decides to live in a shed next door; the palace was the absolute future, the shed the existential present. Engels, one might say, did just the reverse. The Communist future would be an enormous shed; but till it came, he would enjoy the little palace of the present. Appropriately enough, this tension appears even in Engels’s last will and testament. After making a large bequest to Germany’s Social Democratic Party, to advance the proletarian revolution, he went on to instruct the party leader August Bebel: “Drink a bottle of good wine on it. Do this in memory of me.”

This Issue

October 22, 2009