1.

Amid the wreckage of Gaza, Hamas’s officials struggle to sound upbeat. The burly interior minister, Fathi Hamad, whose predecessor was killed by an Israeli bomb, defiantly shuns security precautions at his makeshift office in Gaza City’s main police station. “Claims that we are trying to establish an Islamic state are false,” says the minister, who says his preference would be pursuing a degree in media studies. “Hamas is not the Taliban. It is not al-Qaeda. It is an enlightened, moderate Islamic movement.”

Such talk is not the only effort to return to normality. Parasols and beach cabins sprouted this summer along Gaza’s twenty-eight miles of sandy shore, the crowded strip’s principal public park. Two buildings of the Islamic University, Hamas’s most prominent educational institution, had been bombed but the university put on a graduation ceremony with festive lights, a cascade of multicolored balloons, and heart-shaped posters wishing future success to its students, most of whom happen to be women and some of whom flashed jeans and high heels beneath their black gowns. In a theater next to the Palestinian parliament, also shattered by bombs, actresses danced and writhed in the government-sponsored premiere of Gaza’s Girls and the Patience of Job.

Such events reflect one side of the ongoing conflict inside Hamas between the pragmatists who put Gazans’ needs first, and have sought to lighten their lives after years of punishing blockade and intermittent war, and the ideologues who give priority to “the rule of the sharia of God on earth.” Advocates of the latter have tried to apply Islamic law in full, appealing to the Gaza-based and Hamas-controlled Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) to replace the British Mandate–era penal code with a sharia law that provides execution for apostasy, stoning and lashing for adultery, and the payment of blood money counted in camels. So far, the pragmatists have largely frustrated their efforts. “You can’t Islamize the law when the political system is not fully Islamic,” says the PLC’s general director, Nafiz al-Madhoun, who completed a doctorate in law at the University of Minnesota, and once lectured there. “You need to have an Islamic government, judiciary, and political system. And we don’t.”

In response, the ideologues have resorted to other means, introducing sharia by the back door. With the help of Hamas mosques, the Religious Endowments Ministry has commissioned a morality police to “Propagate Virtue and Prevent Vice,” not least by patrolling the beaches for such signs of debauchery as unveiled female bathers and shirtless men. The police have set up arbitration committees in their stations, offering detainees a fast-track resolution by fatwas, or legal opinion, which sometimes comes from the Muslim Scholars League. “The law of God or the law of a judge?” the police have asked petitioners. The Education Ministry insists it has issued no requirement that schoolgirls wear the jilbab, the shapeless body-wrap, but at the start of the school year, some principals did.

The Islamic Resistance Movement (in Arabic, Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiya—hence Hamas) remains powerful, but nearly four years after winning the 2006 elections, and two years after its gunmen overpowered Palestinian Authority (PA) forces to seize control of the strip, Hamas no longer acts like an opposition suddenly thrust into power. Silent a year ago, the Ministry of National Economy now negotiates with entrepreneurs seeking licenses for their latest project. The ministry’s small-business scheme offers interest-free loans for such things as a $5,000 freezer to put a butcher back in business. The Local Affairs Ministry runs a licensing office for the tunnels to Egypt that remain Gaza’s lifeline; the Public Works Ministry is repaving roads with smuggled tar; the Foreign Ministry has commissioned an American journalist to train diplomats; and the Finance Ministry is collecting taxes with increased rigor. A comprehensive Web site (www.diwan.ps) gives details of government appointments and decrees, with greater transparency than the PA, Hamas’s counterpart in Ramallah that once ran both parts of the Palestinians’ territory, but now runs the West Bank alone, and that under an Israeli thumb.

Hamas has revamped the civil service, pruning departments that under the bloated PA had more undersecretaries than clerical secretaries. Initial protests by Fatah loyalists after Hamas’s takeover in June 2007 gave Gaza’s new masters an excuse to lower pay grades and shed jobs. “It was a gift from God. Most were already redundant,” according to an Interior Ministry official who says he has cut his twelve-member staff (including nine directors-general) by a third. With government salaries paid promptly, most of the time, Gazans make use of strike-free municipal services, including buses and schools. Should Gaza again have a functioning railway, Hamas would run trains on time.

International attempts to isolate Hamas have also helped instead to entrench the Islamists. With all but the most basic goods banned from Gaza, smuggling has thrived through supply lines that Hamas controls. Since 2006, despite Israeli bombing and increasingly effective Egyptian policing, the number of tunnels has grown from a few score to over a thousand. “The siege has empowered those the international community wanted to disempower,” a Gazan businessman observed.

Advertisement

Of the nearly 30,000 people the authorities say have received jobs since the party took power, some 25,000 are in the security forces. “You can dial 100 and the police come,” a banker said. “Under the PA, police were afraid of thieves, now the thieves are afraid of them.” Before the Hamas takeover, says another, he and his friends chose their most battered car when they went to a restaurant, for fear of car thefts. This summer, the jammed streets were full of new cars, a tacit rebuke to Israel’s two-year ban on vehicle imports.

The internal calm is matched by an external reprieve. When Israel withdrew in January, leaving 1,387 Gazans dead (according to the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem), thousands homeless, and factories, schools, and infrastructure smashed, Hamas hailed its survival as a great victory. But Israel imposed its own terms, forcing Hamas to quietly drop demands that Israel lift the blockade before Hamas stopped lobbing rockets at the Jewish state. While the range of Hamas’s rockets has increased from fifteen to forty kilometers, bringing Tel Aviv suburbs within reach, Hamas has, since the end of the Israeli incursion, fired rockets rarely if ever, and restrained Islamist rivals, such as Islamic Jihad, from doing the same. Between March 17 and September 22 Gazans fired some eighteen short-range rockets without loss of life. Israel has responded with incursions and sometimes fatal bombings. In effect, Hamas now acts as Israel’s border guard, preventing further attacks. Israel’s swap of twenty female Palestinian prisoners for the first video footage of Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier Hamas captured three years ago, has raised guarded hopes in Gaza of a bigger deal to come. In exchange for Shalit, according to Hamas leaders, Israel will soon release hundreds of Israel’s ten thousand Palestinian prisoners and might even relax the siege.

To the south too, Hamas hints of better times ahead. Whereas in 2008 Hamas brashly punched a hole through Egypt’s border defenses, unleashing an embarrassing stampede of Palestinians into Egyptian shops, Interior Minister Hamad says Hamas now “coordinates fully” with Gaza’s sole Arab neighbor. Hamas even poses as a guardian of Egypt’s national security, not least by killing al-Qaeda’s self-proclaimed preachers and other adherents in Gaza. “Our task now is governance, to consolidate stability rather than continue resistance,” says Hamad.

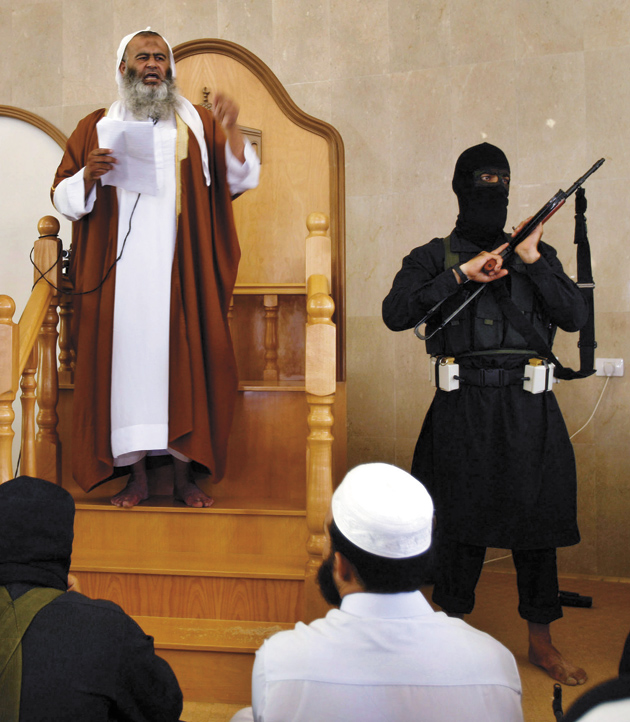

Yet a day after speaking these soothing words, the interior minister offered a very different political horizon. Between towering bodyguards from Hamas’s armed wing, the Qassam Brigades, he delivered an apocalyptic address to a summoned assembly of clan elders. It was angels that chased Israel’s army from Gaza in last winter’s war, he thundered, adding with a numerological flourish that whereas Israel beat twenty-two Arab nations, Gaza’s Islamic resistance had routed the enemy in just twenty-two days. The Jewish state, he concluded, would disappear in 2022.

Such reverses in rhetoric reveal a movement struggling to reconcile two competing audiences: the “international community,” which calls for Hamas to be more moderate, and a core constituency that grows suspicious at any sign it might be selling out. Much as Communist regimes tacked “Democratic” to their names to disguise totalitarianism, Hamas officials use the word “resistance” to hide the waning of their armed struggle. The culture minister, when he attends theatrical productions, speaks of Resistance Culture. The minister of economy hails recent openings of cafés and restaurants as triumphs of the Resistance Economy. “As long as we don’t raise our hands in surrender and continue to struggle, that’s resistance,” he said.

Hamas has failed to achieve the prime requisite for a more normal life: ending the siege. Gaza under Islamist rule is a cul-de-sac. Air and sea routes are blocked. Only the very sick, wounded, or well connected are allowed passage through sporadically opened land crossings to Israel and Egypt. Few now even bother to attempt the humiliating process of crossing the border, either with Israel or Egypt. “You can’t board an Egypt Air plane to get home via Cairo without a fax from Egyptian intelligence,” a Gazan graduate of Harvard Business School said.

While some Gazans profit from the boom in contraband, most people have seen their savings, salaries, and businesses atrophy. For all the talk about entrepreneurs, nine tenths now live below the poverty line, according to the UN, which estimates that living standards have plummeted to pre-1967 levels. In Israel per capita GDP is $27,450; in Gaza it’s two or three dollars a day. Even merchant families collect UN rations.

Advertisement

If war and siege have not crippled Hamas, Gaza’s misery appears to have prompted its greater willingness to compromise and offer its people a political future. Hamas leaders, including the more outspoken exiled leadership based in Damascus, have lately muted criticism of Fatah in the interest of intra-Palestinian reconciliation—even after Abbas’s Palestinian Authority reportedly bowed to Israeli pressure and withdrew its demand for UN action against Israel following Justice Richard Goldstone’s UN report into war crimes by the belligerents in Gaza’s winter war. They have played down the significance of their party’s fiery founding charter, which rejects any recognition of Israel, hinting that they could live with a two-state settlement. In its draft laws, Hamas defines “Palestine” not as the area including Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza but as the geographical district over which the Palestinian National Authority rules. As leaders of Fatah did a generation earlier, some members have discreetly met with Israelis at international conferences, talking peace over breakfast. In addition, within its own fiefdom Hamas’s leaders have decided to suspend declaration of an Islamist state and application of sharia, and to focus on the economy instead.

Such changes in position are offensive to Hamas’s hard-core followers. For what have they struggled, if not for establishing God’s kingdom on earth? Rumors in Gaza reinforce the image of a leadership straying from the straight path. Businessmen working with Hamas are said to be investing tunnel profits in renovating plush hotels, prompting some to speak of an emerging Hamas oligarchy. A minister’s son reportedly deals in drugs, and the son of a Qassam commander smokes water pipes. The security forces, too, seem to be following the pattern of the region’s self-serving police states. Hamas used to threaten external foes and defend its own people, say Gaza’s whisperers. Now it does just the reverse.

After Friday prayers on an August afternoon, Abdel Latif Moussa, a preacher in Rafah, the principal town on the Egyptian border, addressed scores of armed supporters. If Hamas did not have the guts to declare Gaza an Islamic emirate, he said, then he would do so, right here and now. Within hours of Moussa’s sermon, masked fighters from Hamas’s Qassam Brigades surged into the neighborhood. Among the twenty-eight killed were Moussa himself and several Qassam fighters, some felled by the first recorded instance of intra-Palestinian suicide bombing.

This was by no means Hamas’s first sign of ruthlessness toward fellow Palestinians. During the first intifada against Israeli rule, which erupted soon after Hamas’s official founding in 1987, its nascent armed wing targeted suspected collaborators, prostitutes, and drug dealers as often as it did Israelis. Islamists had long clashed with Fatah activists they called “traitorous” before Hamas’s 2007 putsch against them, which culminated in street fighting that left more than one hundred dead. Since then the Qassam Brigades have sprayed gunfire at Fatah demonstrators and knee-capped Fatah organizers until they stopped demonstrating. They have laid siege to rebellious quarters of hostile clans and lobbed rocket-propelled grenades inside until family elders agreed to surrender.

But during August’s shoot-out in Rafah, Hamas was not fighting “traitors,” but rather its own brothers—people who prayed at the same mosques, studied the same texts, tapped the same financial backers, and used much the same terminology that Hamas used to overthrow Fatah. Such ultra-puritan Islamists are broadly known as Salafists, adherents of a belief system originating in Saudi Arabia that seeks to replicate fully the practices of the Prophet’s companions.

Some Salafists have sought to infiltrate the ranks of Hamas, where they find fertile ground for recruits, particularly in its armed wing. Others have fused their search for purity with a jihadist challenge to the established order. Some eschew politics altogether, limiting their activities to preaching. Though dedicated to eliminating foreign influence, their teachers are among Gaza’s most widely traveled, having studied in South Africa, Pakistan, Yemen, and Europe. Moussa had studied under such teachers in the Khan Yunis town, before shifting to the jihadist track.

Cracks emerged when Hamas drifted from social activism and armed struggle into politics. After Hamas decided to contest the 2006 elections, one of its preachers in Rafah left the movement with scores of followers. God’s will above man’s, he said, and besides Hamas had no business participating in an authority established by agreement with Israel. During the contentious interregnum of national unity government before Hamas’s takeover of Gaza in June 2007, both Fatah and Hamas solicited Salafist support. Unruly clans seeking an Islamist cover to press their claims bolstered their ranks. Amid the chaos, the Salafists sought to enforce their authority by waging a nasty morality campaign against Internet cafés, hairdressers, the American school, and other such places of ill-repute.

Armed confrontation with the Salafists followed fast on the heels of Hamas’s takeover. In July 2007 the Qassam Brigades laid siege to the stronghold of one jihadist group, the Army of Islam, forcing the release of the BBC’s kidnapped correspondent Alan Johnston.

In the months that followed, Hamas fought to extend its control, sending the members of the Army of Islam fleeing to other towns. There they sought to rally support among discontents, challenging Hamas’s legitimacy with harder-line Islamist rhetoric that accused it of selling out both on its application of sharia and its resistance against Israel. They set up new cells, variously claiming affiliation with al-Qaeda and ridding Gaza of idolatry with such acts as removing the statue of Palestine’s unknown soldier from Gaza City’s central square.

One of the largest factions, the jaljalat—Arabic for “the reverberations of thunder”—acquired significant support inside Hamas, and sought to target high-profile visitors to Gaza, reportedly including former President Jimmy Carter. Jund Ansar Allah, the Army of God’s Companions, led by Moussa, was a relatively new addition. Its operations included a cavalry charge by white stallions intended to emulate early Muslim warriors, notwithstanding the landmines on Israel’s fortified border. Qassam Brigades stormed a house in the Khan Yunis refugee camp used by the Jund in mid-July, uncovering money, weapons, and explosive belts. Soon after, a bomb blasted the wedding of a nephew of Fatah’s former strongman in Gaza, Mohammed Dahlan, wounding sixty-one. It was after this that Qassam forces targeted Moussa’s base in Rafah, the Jund’s strongest redoubt with its easy access to tunnels and regional support. Salafists fleeing Rafah found refuge further north, sparking more clashes around Gaza City when Hamas sought to capture them. In two days, Hamas officials said they detained 250 Islamists.

In an attempt to deflect a Salafist backlash, Hamas officials have made a show of honoring the Jund’s dead as martyrs, along with their own. They have sought to reaffirm their Islamist credentials with a morality campaign called Fadila, or Virtue, intended to tighten the Islamists’ spiritual grip. The Religious Affairs ministry has hired seven hundred new employees to regulate public mores, by such actions as checking couples’ marriage licenses.

A sense of unease is again enveloping Gaza. Ramadan, a time of festivity, proved desultory, and not just because of the siege. In what is Hamas’s greatest security breach to date, Salafist Web sites published hit lists of Hamas members, detailing their rank in the movement, their tunnel hideouts, and mosques where they can be targeted. Jihadist spiritual mentors did not endorse calls for revenge attacks, and some instead urged unity and calm. But Gaza’s streets and mosques were noticeably more subdued after the Rafah bloodshed. Hamas checkpoints—which had all but disappeared from the Gaza Strip—reappeared in the heart of Gaza City, sometimes during daylight hours. The few foreigners Israel allows to visit, who for months had experienced a brief respite, relaxing on its beaches and Web surfing in its wi-fi-equipped cafés, now tend to venture into Gaza in armored cars.

Hamas’s resilience and ingenuity in the face of intense challenges are a largely untold success story. But its drive for a monopoly of power has swept aside the consensus-building that exemplified Palestinian politics and replaced it with a one-party statelet. Few believe Hamas wants elections anytime soon. Despite the lip service they pay to the electoral process, its leaders are wary of the large part of the Palestinian public that sullenly blames them for prolonging Gaza’s troubles.

Without elections there is scant outlet for organized civil dissent. Opponents seeking to hold Gaza’s authorities to internal account have few means but force. Hamas claims that it has crushed “the deviants,” but in doing so it has deployed the same mosque-storming tactics Fatah once used against it, arousing scorn over its methods. In the absence of a more inclusive approach, Hamas’s greatest achievement—the restoration of Gaza’s stability—sometimes feels as bittersweet a prize to ordinary Palestinians as the “victory” it claims over the Zionist enemy.

2.

In a sense, Hamas has become captive to its own success as it struggles now to reconcile the pressing needs of day-to-day governance with the ideology it preached in opposition, and to reconcile as well its Palestinian cause with its wider Islamic one, and its cult of guns and martyrdom with more pragmatic instincts. As several useful new books on Hamas reveal, such gnawing internal tensions are inherent in the approach that Islamists have adopted to the question of Palestine from its very origins. Seeing the “cause” in millennial terms, as part of a universal struggle, the faith-based movement has badly damaged a polity that was fragile and inchoate before the implantation of Israel, and has struggled mightily to remain unified ever since.

Although Hamas itself is not yet a quarter-century old, it is important to recall that the earliest armed resistance to Zionist colonization was not nationalist, but rather pan-Islamist in inspiration. In his gossip- and fact-packed book Inside Hamas, Zaki Chehab, a pro-Fatah Palestinian journalist, reminds us that the namesake of Hamas’s Qassam Brigades was, in fact, a Syrian who was educated at Cairo’s al-Azhar University. When France occupied Syria in 1920, Ezzedine Qassam briefly led an armed cell, but soon fled to the safety of British-occupied Palestine. As a mosque preacher in Haifa he witnessed the surge in Jewish immigration that followed Hitler’s rise, and began a clandestine campaign to arm Muslim fighters.

Qassam himself was “martyred” by British troops in 1935, at the start of the Palestine Revolt, and then largely forgotten until his memory was revived by Hamas. The uprising he helped inspire was eventually crushed by the British, who in the process effectively decapitated the Palestinians’ nascent leadership. This weakness, compounded by class tensions within Palestinian society, as well as by the marginalizing of its Druze and Christian minorities, proved fatal ten years later, when the better-led, better-equipped, and desperately determined Jewish Yishuv conquered most of historic Palestine.

The 1948 Nakba, or Calamity, left the Palestinians, still leaderless and now physically dispersed, particularly susceptible to Islamist ideas, and to the romantic notion of guerrilla action. Not only had secular Arab armies proved incapable of defending them, but the success of the Jewish state seemed to present an object lesson in the potential of religion as a political force. The displacement of thousands of Palestinian peasants to refugee camps, meanwhile, created conditions of dislocation, squalor, and unemployment similar to those that were to fan Islamist trends in urban slums across the region.

Not surprisingly, much of the future generation of Palestinian leaders, including Yasser Arafat, entered politics as members of the Muslim Brotherhood, the fiercely anti-imperialist, pan-Islamist movement founded in Egypt in 1928. Even before 1948, according to Jeroen Gunning, a British academic whose Hamas in Politics is an exemplary political primer on the Islamist party’s evolution, structure, and thought, the Brotherhood was said to have thirty-eight branches in Palestine, with ten thousand members. Ironically, Arafat’s founding of Fatah, the secular party that dominated Palestinian politics until the 1990s, was prompted not by a rejection of Islamist ideas but by the Brotherhood’s move, under intense and frequently brutal pressure from Arab regimes, to abandon “armed struggle” in the 1950s.

A generation later, the resurgence of Islamism among Palestinians very much paralleled its rise across the wider Muslim world. A first generation of degree holders, many of them engineers and doctors, were radicalized not just by Israel’s occupation and colonization of the West Bank and Gaza after the 1967 war, but also by the limited room for advancement within Palestinian society. Blaming the Arabs’ cosmopolitan elite for their series of defeats, the Islamists sensed their own entitlement to power, both as more authentic representatives of the masses and as the true heirs to a tradition of resistance that they saw as being cultural as much as political.

Paul McGeough, an Australian reporter who has written a fascinating account of the rise of Khaled Meshaal, Hamas’s most prominent leader today and the chief of its politburo, quotes him as scoffing at his rivals with the words, “We’re the root; Fatah is a mere branch.” Even at university in Kuwait in the 1970s, where his mosque-preacher father settled after fleeing his West Bank village in 1967, Meshaal refused to join the existing, Fatah-dominated Palestinian students’ union, but insisted on creating a parallel Islamic one. Under his guidance Hamas later refused to join the PLO, the umbrella grouping of Palestinian parties. Hamas also refused to coordinate with others during the 1987–1992 intifada, and refused to participate in national elections before 2005. To the frustration of others it saw itself alone as the Palestinians’ rightful leader.

When the Palestinian mainstream moved, during the 1980s, toward compromise with Israel, Islamist factions shifted into outright opposition. While the Muslim Brotherhood had retained a network inside Palestine, based in mosques and student clubs, Khaled Meshaal and a group of younger Islamists in the diaspora had formed a network of their own, collecting funds from Palestinian workers in the wealthy Gulf states. Their dual effort merged in the creation of Hamas. By the time Yasser Arafat signed the first peace deal with the Israeli enemy in 1993, establishing a proto-state under his rule in Gaza and the West Bank, the new party had the means and determination not merely to challenge his course, but to sabotage the entire “peace process.”

Its effort, pursued mainly by means of a bloody series of bombings targeting Israeli civilians beginning in 1994, brought Hamas global notoriety but not, at first, much popularity among its own people. For most of that decade, Jeroen Gunning writes, opinion polls rarely showed the Islamists gaining more than 20 percent approval, a level that broadly reflected the performance of similar Islamist parties in other countries. Hamas’s slow ascent to victory in the 2006 election came largely as a result of bungling by all of its adversaries.

Indeed, Israel’s mishandling of Hamas began even before the group’s creation. The Israelis turned a blind eye to recruitment by the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1970s and 1980s, largely because they saw the Islamists as a foil to nationalist groups. Belatedly alerted to the arming of Hamas cells during the first intifada, Israel increased its appeal by televising the trial of Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the wheelchair-bound Gaza preacher who was Hamas’s spiritual head, and then by exiling hundreds of Hamas activists to Lebanon, where they had a useful chance to make contact with fellow Islamists such as Hezbollah.

Hamas’s subsequent resort to hideous “martyrdom operations,” as suicide bombings were called, owed much to Hezbollah’s inspiration and perhaps also to its technical expertise. Israel’s response of targeted assassinations hugely bolstered Palestinian sympathy for Hamas, even as it served to radicalize its followers. As Paul McGeough’s book makes abundantly clear, for instance, Khaled Meshaal, a relative hard-liner, rode to dominance within Hamas on the wave of outrage that followed Israel’s botched attempt to poison him in Amman in 1997. By contrast, when in 2003 Israel succeeded in murdering Ismail Abu Shanab, a respected Gazan intellectual with an engineering degree from Colorado State University, it eliminated a Hamas official who had argued passionately against suicide bombings and in favor of a long-term truce.

Israel’s dramatic acceleration of Jewish settlement in the occupied territories during the 1990s, and its systematic undermining of the Palestinian economy by means of roadblocks and closures, convinced many Palestinians that Hamas was perhaps correct in judging the peace process a sham. Even as Yasser Arafat’s credit waned among his own people, both Israel and the Clinton administration pushed him to crack down on Hamas. This he did, with some brutality and considerable success, in a campaign that put hundreds of Hamas activists into Palestinian prisons. Yet rather than being rewarded for risking the anger of his own people, Arafat was simply pressured to do more, and told that he would be held to account for any atrocity carried out by Hamas.

In effect if not in intention, Israel handed the Islamists veto power over the peace process. It also so weakened Arafat that when Israel floated the possibility of an offer at Camp David in 2000, the Palestinian leader shied from pursuing it, largely because he feared he could not swing his people to support it. When, in the autumn of 2000, the second intifada broke out in the wake of this failure, Arafat felt obliged to ride the violence rather than attempt to contain it, and soon lost control of his movement as local Fatah activists strove to outdo Hamas in fury.

Arafat was hardly a mere victim. His Fatah party proved just as helpful to Hamas as their mutual enemy. Not only did his suppression of the group smack to many Palestinians of treachery but Arafat’s cronies were notoriously corrupt and incompetent. Their handling of the 2006 legislative elections that swept Hamas to power, brilliantly described by Gunning, was almost farcically self-destructive. As Zaki Chehab quotes a Gazan voter telling him at the time, “We don’t believe in Hamas’s political views, but we want to show the Fatah leadership that we have alternatives.”

Yet Hamas may also claim much credit for its success. In stark contrast to Fatah, it has acted with strategic vision, careful planning, and steely discipline. Much of its leadership has deeper local roots, and is generally of a higher caliber: in the cabinet it formed after the 2006 election, no fewer than seven of its twenty-four ministers held advanced degrees from American universities. Politicians such as Meshaal are far more charismatic on television than Arafat’s hapless successor, Mahmoud Abbas.

With its clandestine structure of local cells and a dispersed leadership that operates by consensus, Hamas has proved extremely resilient to attack. Despite the bloodiness and apparent futility of its methods in combating Israel, it has shown both a high degree of managerial competence and a responsiveness to Palestinian public opinion that can be surprising for a religiously inspired organization. Yet the need to placate its ideological core, combined with Hamas’s evolution of a structure that links Meshaal and his money, safely offshore, directly to Qassam commanders, so bypassing political scrutiny by their less strident colleagues, also builds in rigidity on key issues, most obviously that of peace. Sadly, Hamas’s inflexibility has often proved, in the eyes of its constituents, to have been vindicated by events.

Hamas is unlikely to be budged anytime soon from its Gaza stronghold. It is playing a waiting game, hoping that other forces will blink before it does: that the international community will feel shamed into relieving the siege of Gaza, or that Egypt’s hostile regime will fall, or that Benjamin Netanyahu’s Israel will prove so stingy in its dealings with Mahmoud Abbas that the Fatah government on the West Bank will collapse. But in the meantime Hamas is under pressure to deliver something more than bravado to its people. Perhaps, as Gunning suggests, it will one day admit that its armed struggle against Israel (unlike against its internal rivals) has been largely symbolic, and that its declaration of a divine right to Palestine represents more of a credo than a political program. Gunning declines to judge whether, with regard to hopes for Middle Eastern peace, Hamas is what political science would term an “absolute spoiler,” or only a limited one. But as he says, politics is never static, nor are political organizations.

—Gaza and Cairo, October 6, 2009

This Issue

November 5, 2009