1.

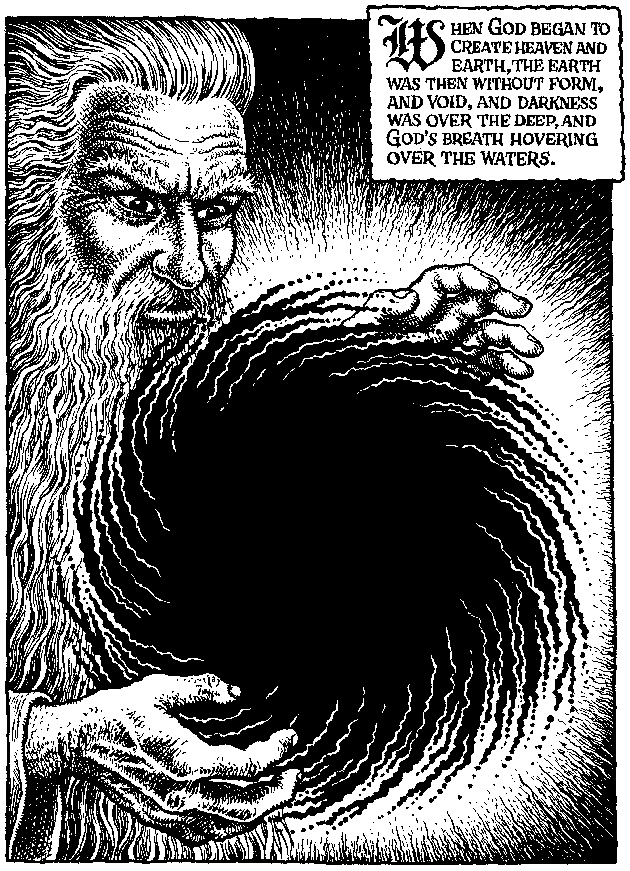

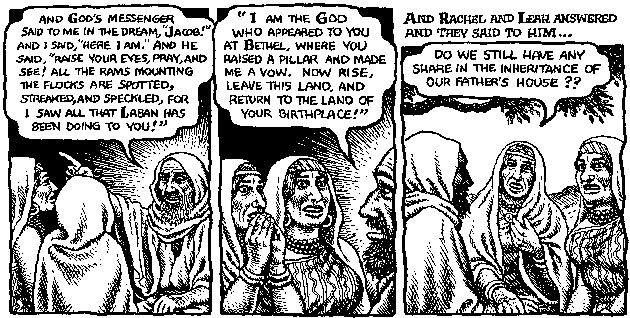

Illustrating the Hebrew Bible has been a grand quest for painters, with Michelangelo and Tintoretto perhaps dividing the palm. A cartoon or comic book reduction of Genesis ideally should be the work of an unlikely fusion of Rembrandt and William Blake. That is not a fair criterion to invoke when considering R. Crumb’s venture into the Book of Genesis. Staring at the women and men of Crumb’s Genesis, I dimly recall someone showing me an issue of Mad magazine. To my untutored view the work of Crumb recalls that publication yet somehow also is touched with what I remember as the doughty proletarian style of Ben Shahn. At the least, Crumb’s cartoons have the initial merit of strangeness in their portrayal of the patriarchs and matriarchs of the first book of the Hebrew Bible.

“Strangeness” is a very rich term and needs narrowing down here. The people of Genesis are indeed picturesque but powerfully ugly in Crumb’s vision. I do not regret the men but the women, from Eve to Rachel, are so dreadful that I am made unhappy. They hardly suffice even if you try to defend Crumb’s approach as one of a healthy realism. What reply could suggest itself to me if a Crumb admirer asserted: “That is what they really looked like, back then”? There was no “back then.” Genesis, like Exodus and Numbers after it, is fabulous tale-telling, and not historical fact. You can call it myth if you want to or whatever you think best fits the tale of the tribe.

The sages said that there were “seventy faces to the Torah”; they might as well have said seven hundred and seventy-seven. By “faces” they meant interpretations, but viewing Crumb I literalize their metaphor and wish he had indeed limned seventy faces. I may put it too drably yet I seem to see just two Crumbian countenances in his Genesis, one female and one male. That may be his dark wit, and I will abandon him awhile for the text of Genesis itself, and then for some personal history of reading the most beautiful modern retelling of Genesis, by Thomas Mann in his tetralogy Joseph and His Brothers.

2.

The central literary character in Genesis is Yahweh or the God. I mean this precisely in the sense that the richest literary character in Shakespeare’s Henry IV plays is Sir John Falstaff, or is Prince Hamlet in his tragedy, or is the Knight of the Sad Countenance in Don Quixote. To assert that the worship of God by Muslims, Christians, and Jews is prayer and praise for a literary character is a reasonable observation but still not advisable in Muslim countries. Even in the United States there are many millions of people who are offended if told that they believe in a literary character, whether the Yahweh of the Hebrew Bible or the Jesus of the gospels or both. Since I myself believe in Falstaff, Hamlet, and Don Quixote, I would be inconsistent not to believe in Yahweh and in Mark’s Jesus, two astonishing literary characters.

Judaism does not require me to believe in Yahweh but rather to trust in him. I recall once writing that I don’t like him, I don’t trust him, I wish he would go away, but as the strongest of all literary characters he won’t. Homer (or the Homers) gave us Achilles and Odysseus, and Homer’s only possible literary rival, the Yahwist or J writer, earliest author in the Torah, gave us Jacob and Joseph and Tamar, but above all presented us with Yahweh, the supreme fiction among all Western literary personages. Yahweh in Genesis, Exodus, and Numbers is Very Bad News. He is human all too human, surpassing Jacob and Joseph, Achilles and Odysseus. As the God he is crafty, daemonic, jealous, curious, brilliant, cruel, irascible, humorous, above all unpredictable. He defines the uncanny. His name, he says, is Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh, which I translate rather fully as: “I will be present (where and when) I will be present.” The converse is equally true: “And I will be absent (wherever and whenever) I will be absent.” The history of the Jews is the consequence of that willed absence.

3.

What precisely is the Book of Genesis? The stories are familiar: Adam, Eve, and the Serpent; Cain and Abel; Noah and the Flood; the Tower of Babel; Abraham and Sarah; the Akedah, or intended sacrifice, when Isaac nearly is killed by his father Abraham; Jacob, Esau, and the Blessing; Jacob’s all-night wrestling with one of the Elohim; and finally the grand saga of Joseph and his brothers.

I have left out Yahweh, yet Genesis is as much his book as Othello is Iago’s play or The Merchant of Venice is Shylock’s. Yahweh in Genesis is no sky-god but shares the ground with Abraham and Jacob. One should note that the Jacob and Joseph story takes up half of Genesis, Chapters 27–50, and yet the title assigned by the early translation into Alexandrian Greek (and later into Latin) renders the first word of the scroll, Bereshith, Hebrew for “in the beginning.” What begins in Genesis is not only humankind but also Yahweh the God. Unfathered and without origin, he ought to be the most mysterious of gods but that is not how his author, the Yahwist, treats him. He walks about, accepts being argued with by Abraham, and happily devours a copious luncheon prepared for him by Sarah.

Advertisement

Current scholarship tends to dismiss the older hypothesis of a distinct, continuous Yahwist strand or “source” in the Torah, but I am skeptical about the rise and fall of fashions in this domain. Of course preexisting texts and themes have been identified, but the notion of a concourse of tiny fragments gradually being pasted together into the Torah seems to me an absurdity, an insult to any authentic literary mind. A strong authorial personality comes through in the Yahwist parts of the Five Books of Moses. Unlike the Priestly portions, the Yahwist text is refreshingly secular, frequently ironic, and seems to delight in its own outrageousness, as when Jacob tricks Esau out of his father’s blessing. I honor Crumb for implicitly sensing this, even though it is not at all a view favored by the eminent translator Robert Alter, whose version of the Hebrew is for the most part employed here.

Staying with Crumb’s representations may not be delightful but his position toward the story is very refreshing. He is free of stale pieties and he properly has no use for the Priestly sentiments preserved in Genesis. The moral insanity of making divine justice an excuse for human suffering is alien to Crumb. Whatever aesthetic unease I feel in regard to his women is more than answered by his healthy wariness of Yahweh, a sanity I attribute to his graphic exuberance.

4.

I remember my own childhood reaction to Genesis as being unhappiness with Yahweh, mixed with awe. The unhappiness has matured into uneasy rejection (something I was not raised to do) yet the awe remains, since no other person in literature is so uncanny. One has to say “person” because the Yahwist created a personality, a God whose dynamism is uncontrollable, even by himself. Doubtless Yahweh came into being before the Yahwist, but we have no record of it. As he appears in Genesis, Exodus, and Numbers he seems as much his author’s work as Falstaff was Shakespeare’s or Panurge was Rabelais’s. Vitalistic characters in literature—you can add the Wife of Bath and Sancho Panza to Falstaff and Panurge—seem always to have been there, and Yahweh belongs to their florabundant company. We ought to enjoy him as we take pleasure in them, but I admit we cannot, since no one builds temples, cathedrals, and mosques to those more innocent heroic vitalists.

Crumb clearly regards all lingering faith that Genesis is a still-binding Word of God as so much contemporary madness and his drawing works as an art of estrangement. Probably, his illustrated Genesis would have aided me in my 1930s childhood, had it been available. An ardent Blakean before I was ten, I visualized biblical personages in Blake’s mode, which had affinities to eighteenth-century parodic caricaturists like Rowlandson and Gillray.

My wife tells me that she was given a Bible comics by her grandfather during her 1930s childhood, but I never saw it. My own encounter with an equivalent came in the New York Daily Mirror, August to September 1944, a running cartoon series of Thomas Mann’s Joseph the Provider, illustrations by C.B. Falls, in the then-new translation by H.T. Lowe-Porter. To my fourteen-year-old eyes, Falls was routine stuff, but the cartoon presentation led me to Mann’s great tetralogy, Joseph and His Brothers (not collected until 1956). Even at fourteen I felt a sense of diminishment as I went from the wonderful Tales of Jacob on to the almost as charming Young Joseph and then the rather inadequate Joseph in Egypt and the tiresome Joseph the Provider, where Joseph assumed the role and manner of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Lowe-Porter’s translation now reads like a parody of the King James Bible’s Genesis, and happily has been replaced by the admirable 2005 version of John E. Woods. I have just reread Mann’s saga for the first time in twenty years, and though the progressive decline from volume to volume still is there, Woods recovers The Stories of Jacob and Young Joseph so that they deserve to stand with his translations of Buddenbrooks, The Magic Mountain, and Doctor Faustus.

Advertisement

In 1990, I published The Book of J, much influenced by Mann’s Joseph saga, for the German master permanently recaptured the ironies of the Yahwist, which I wished to bring forward again. The Yahwist and Mann alike emphasize the beauty of Rachel and her son Joseph, which clashes with Crumb’s visual imagination, but disarmingly Crumb says: “I’m not very good at drawing attractive women actually.” Mann’s homoeroticism warms his treatment of Joseph, whose impishness also delights Yahweh. I relish the great Bible translator William Tyndale on this: “And the Lord was with Joseph, and he was a lucky fellow.”

Mann’s triumph is his Jacob, who is very close to the Yahwist’s original and in Mann as in Genesis rather close to Yahweh himself. Yahweh and Jacob are crafty tricksters, adept at evading consequences. The Blessing of Yahweh stays with Jacob and Joseph even as later, in the Book of Samuel, it will be conferred on David. But what is the Blessing in the Hebrew Bible? I have taught myself to translate it as a promise of “more life” going on into “a time without boundaries.” Whatever the darker aspects of Yahweh—and they are myriad—this is his glory, if we could believe even that.

Mann’s Yahweh has an uneasy relationship to his heavenly retinue, who resent the creation of man and who sense that their ambivalent God seeks to improve himself by becoming more conscious through awareness of human suffering. The Yahwist has no such illusions about a maturing Godhead. In Exodus 4:24 Yahweh attempts to murder poor Moses when the reluctant prophet is asleep at a night encampment in the Negev on his way back to Egypt. No justification or explanation is provided. Yahweh’s dreadful intention is particularly abominable since Moses gave in after his sensible attempt to evade his election by Yahweh. Neither we nor Moses ever come to understand why Yahweh has chosen him, let alone the sudden will to murder him in the wilderness night.

5.

Mann’s beautiful Prelude to Joseph and His Brothers is titled “Descent into Hell,” but that is another irony since the actual immersion is into the primordial past. In section 8 of the Prelude, Mann identifies his Joseph with the myth of the primal man—gnostic, hermetic, kabbalistic—who was both androgynous and divine, and who fell in love with his own watery reflection, and so fell indeed, outward and downward into our material world of space and time. Mann speaks of this man, who will become his Joseph, as a “narcissistic image so full of tragic charm.” He might be speaking of himself, now that the homoerotic secret of his own life has been divulged to his admirers, though Death in Venice and other masterworks by him should have informed us in any case.

The Hebrew Bible could not be clearer that the four-letter YHWH is God’s true name, since it is employed more than six thousand times. Yahweh must be a very old name, since it is what the God is called in the great war song of Deborah and Barak (Judges, Chapter 5), which may go back to the twelfth century before the Common Era. No one could call Yahweh a “narcissistic image so full of tragic charm.” He is a whirlwind, a fire, a battle cry, himself a man of war, and most himself when uttering rhetorical questions.

Yahweh has a preference for patriarchs but the Yahwist prefers matriarchs (as does Crumb). Mann singles out Tamar, who seduces her father-in-law Judah, in order to secure her and her sons by him a place in the Blessing (Genesis 38:6–27). For me, at least, the saving interlude in Joseph the Provider is the story of Tamar. Slyly, Mann has the immensely aged Jacob fall in love with Tamar, and then prevail upon his son Judah, heir of the Blessing, to marry her in turn to his two sickly sons, Er and Onan. When Yahweh kills them both, Judah denies Tamar his only remaining son. Her Jacob-like expedient is to disguise herself as a prostitute and have him beget two sons upon her, one of whom will be King David’s ancestor. Mann celebrates her vitality and her will, certainly Yahwistic qualities.

I regret not being more gracious to Crumb, who has returned me to Genesis, to meditate again upon Yahweh, who for me is an endless cause of meditation as are Falstaff and Hamlet. Yahweh keeps assuring the Patriarchs that he desires a Covenant with them, and they are eager to trust in his word. He may hold the universal and eternal record for untrustworthiness among all gods and examples of godliness. One could wish that Thomas Mann, and not the Yahwist, had been his prime author.

This Issue

December 3, 2009