Snark/Art Resource

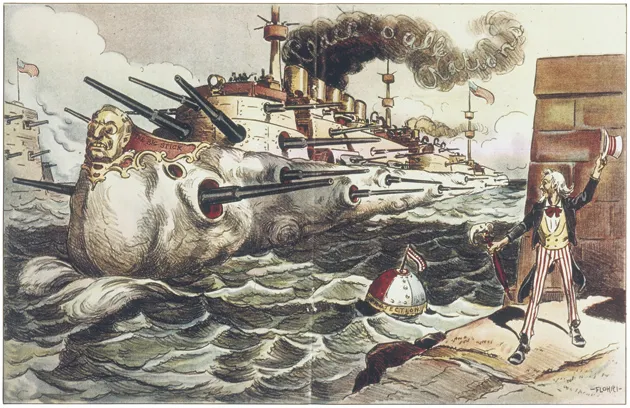

‘Why not build the new 100,000-ton battleship in this shape?’; a caricature by Emil Flohri lampooning Theodore Roosevelt’s aggressive foreign policy, with his bust and the words ‘The Big Stick’ decorating the prow of the ship and the phrase ‘Peace to all Nations’ billowing out of the smokestacks, published in Judge magazine, 1907

1.

Mark Twain managed to name the Gilded Age almost before it had begun. The contentious decades that followed the Civil War have carried other names—the Age of Innocence, the Age of Reform, the Brown Decades.1 But the title of Twain’s novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, co-written with his friend and neighbor Charles Dudley Warner and published in 1873, captured a fundamental ambiguity in how the period is remembered. While the Gilded Age has come to be associated with the fashionable sporting society or “gilded youth” of Newport and Saratoga, as portrayed in the novels of Edith Wharton and Henry James, Twain meant the phrase ironically, to describe the hucksters and cheats who ushered in not a golden age, that pastoral dream of social harmony and material abundance in ancient Greece, but only a gilded one, concealing the dross beneath.

“Who shall say that this is not the golden age of mutual trust,” Twain wrote, “of unlimited reliance upon human promises?”

That is a peculiar condition of society which enables a whole nation to instantly recognize point and meaning in the familiar newspaper anecdote, which puts into the mouth of a distinguished speculator in lands and mines this remark:—“I wasn’t worth a cent two years ago, and now I owe two millions of dollars.”

While the period was conspicuous for its unregulated boom-and-bust economy and the mushrooming new fortunes of men like J.P. Morgan and Andrew Carnegie—what the historian Jackson Lears calls the “galloping conscienceless capitalism of the Gilded Age”—it also featured an unsavory war with Spain in Cuba and the Philippines; the “winning of the West” (the title of a popular book by Theodore Roosevelt) and the almost complete finishing off of the “vanishing” Indian; two severe depressions; the armed suppression of strikers demanding an eight-hour workday rather than the customary twelve; and so many vigilante murders of innocent black men that Mark Twain, in 1901, proposed renaming the country the “United States of Lyncherdom.”

For many historians, the figure who best embodies the conflicts of the period, a man “gilded” in both senses of the word, is the blustering trust-buster and Rough Rider himself, Theodore Roosevelt. His steep ascent from Harvard-educated amateur historian and advocate for the “strenuous life” to public servant as, successively, police commissioner in New York City, assistant secretary of the navy, cavalry officer in Cuba, governor of New York, vice-president, and then, after McKinley’s assassination in 1901, a popular two-term president seems to reflect the possibilities for self-invention during the volatile Gilded Age.

Roosevelt has inspired later politicians, most recently John McCain, who claims his legacy of strategic intervention in business, protection of the wilderness, and robust foreign policy.2 It has proved difficult to puncture Roosevelt’s inflated reputation as the enemy of big business, although he broke up relatively few trusts. According to Richard Hofstadter, in his book The American Political Tradition, Roosevelt was a master of ambiguities:

The straddle was built like functional furniture into his thinking. He was honestly against the abuses of big business, but he was also sincerely against indiscriminate trust-busting; he was in favor of reform, but disliked the militant reformers. He wanted clean government and honest business, but he shamed as “muckrakers” those who exposed corrupt government and dishonest business…. Such equivocations are the life of practical politics, but…Roosevelt had a way of giving them a fine aggressive surge.

Writing in 1948, when memories of Hitler and Mussolini were still fresh, Hofstadter assessed TR’s style of leadership in relation to theirs, finding that this “herald of modern American militarism and imperialism” embraced many of the tendencies of authoritarian regimes, including “romantic nationalism, disdain for materialistic ends, worship of strength and the cult of personal leadership…a grandiose sense of destiny, even a touch of racism.” He concluded that much of Roosevelt’s violence was verbal, however, and that his boisterous writings, despite occasional insight, consisted of “a tissue of philistine conventionalities, the intellectual fiber of a muscular and combative Polonius.”

2.

In Rebirth of a Nation, Jackson Lears treats as tragedy what Hofstadter viewed as farce; he considers Roosevelt a far more sinister figure than he appears in Hoftstadter’s lenient and occasionally affectionate assessment. Lears explicitly attacks Hofstadter, among the most influential American interpreters of the post–Civil War decades, for “writing the history of winners.” Lears, a professor of history at Rutgers and the editor of the journal Raritan, has written incisively about the period before. In his landmark study No Place of Grace (1981), he examined what he called “antimodern” traits during the Gilded Age: the tendency in such developments as the Arts and Crafts movement and Henry Adams’s embrace of medieval France to adopt cultural values from an earlier and seemingly more “authentic” time and place. Lears has also written about the rise of the American advertising industry and what he calls its “fables of abundance.” In both cases, he examined the uneasy adjustment of Americans to a modern urban, commercial, and industrial society.

Advertisement

His new book draws on kindred concerns, with a more indignant edge regarding the sufferings of ordinary people. In his view, what he calls the “Age of Roosevelt,” with all its collective fantasies of regeneration and national greatness, was conspicuous for its losers: blacks, Indians, immigrants, workers, and victims of American military adventures abroad. If Hofstadter contrasted Roosevelt with Hitler and Mussolini, with some confidence that “it can’t happen here,” Lears has in mind a more immediate comparison with George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, and the ways in which the “war on terrorism” has “revived all the old, destructive fantasies—the belief in America’s capacity to save the world; the faith in the revitalizing powers of combat; the cult of manly toughness in foreign policy.”

Lears identifies two strains of American aspiration during the period between the Civil War and World War I. The first is “a widespread yearning for regeneration” and rebirth: “As daily life became more subject to the systematic demands of the modern corporation, the quest for revitalization became a search for release from the predictable rhythms of everyday.” Regimentation in the workplace and relative comfort at home gave rise among the middle and upper classes to fears of “overcivilization” and “a sense that they had somehow lost contact with the palpitating actuality of ‘real life.'” The desire for revitalization, Lears believes, was “rooted in Protestant patterns of conversion” and “resonated with the American mythology of starting over, of reinventing the self.”

The second tendency, reflected in Lears’s title alluding to D. W. Griffith’s 1915 Civil War film The Birth of a Nation, was a yearning for the thrilling excitement of the battlefield:

Militarist fantasy runs like a red thread from the Civil War to World War I, surfacing in postwar desires to re-create conditions for heroic struggle, coalescing in the imperialist crusades of 1898, overreaching itself in the Great War and subsiding (temporarily) thereafter.

Lost in such fantasies were the reasons for making war in the first place, as in the case of the Civil War itself. “Yankees and Confederates made peace,” Lears maintains, “on the backs of blacks.” The South redrew racial lines after the so-called Compromise of 1877 accorded control of the White House to Northern Republicans in exchange for the lifting of the Northern occupation and an infusion of investment in Southern railroads and infrastructure. Slavery was not mentioned when Confederate and Union veterans of Gettysburg gathered to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the battle, and no one remembered that black soldiers had contributed to the Northern victory. W.E.B. DuBois, on the barely noticed fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, offered a Swiftian “Mild Suggestion” to solve “the Negro Problem”: mass extermination of black people by poisoning.

3.

No one created more “conditions for heroic struggle” than Roosevelt. The bullied boy with weak eyes and a puny physique, who was mortified that his own father had paid a replacement to serve in the Civil War, grew up to become what Lears caustically calls the “poster boy for white-male renewal,” practicing judo in the White House and adopting a “muscular” foreign policy. Lears quotes Roosevelt’s incendiary remarks about Indians: “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.” Leading his band of cowboys and Ivy League athletes in Cuba, Roosevelt boasted that he had killed a Spaniard on San Juan Hill with his bare hands, “like a Jack-rabbit.”

Lears concedes that Roosevelt expressed anxieties about the “softening” of American society that were widespread among his peers, and writes well about what he calls Roosevelt’s “careful primitivism”—the selective adoption of the “barbarian vigor of peoples he deemed racially inferior to his own.” What he cannot forgive is Roosevelt’s imperialist aspirations, built on the same distinction between barbarian and civilized behavior. Even before the American declaration of war in support of Cuban independence, Roosevelt in his capacity as assistant secretary of the navy had sent a secret order to Commodore George Dewey to attack Spanish forces in the Pacific in case war should break out. Dewey, supported by Filipino insurgents, laid siege to Manila and forced the surrender of the Spanish garrison.

Advertisement

The treaty with Spain that ended what John Hay called the “splendid little war” ceded the Philippines to the United States for $20 million, along with Puerto Rico and Guam. Instead of declaring an independent Philippines, however, the United States secured the beginnings of an empire, which it proceeded to defend, as it turned out, against the very same insurgents, now branded as terrorists, who had supported Dewey in the first place. According to Lears, issues raised by the treaty “have haunted US foreign policy down to the present.”

Some of Lears’s best pages are devoted to the American dissenters from the imperialist agenda, such as William James, who wrote, “God damn the United States for its vile conduct in the Philippine Islands.” Unimpressed by the Republican pledge in the party platform of 1900 to bring Christian sweetness and light to the “dark places of the earth,” Mark Twain wrote a savage polemic called “To the Person Sitting in Darkness”:

Shall we go on conferring our Civilization upon the peoples that sit in darkness, or shall we give those poor things a rest? Shall we bang right along in our old-time, loud, pious way, and commit the new century to the game; or shall we sober up and sit down and think it over first? Would it not be prudent to get our Civilization-tools together, and see how much stock is left on hand in the way of Glass Beads and Theology, and Maxim Guns and Hymn Books, and Trade Gin and Torches of Progress and Enlightenment (patent adjustable ones, good to fire villages with, on occasion), and balance the books, and arrive at the profit and loss, so that we may intelligently decide whether to continue the business or sell out the property and start a new Civilization Scheme on the proceeds?

Lears’s condemnation of Roosevelt’s imperialist leadership is so complete that even Roosevelt’s apparent achievements are sharply qualified in his account. One might think that Roosevelt deserved some credit for brokering the peace between the warring parties in the Russo-Japanese War, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize. Not at all. “In the far East, where TR could not throw his weight around so easily, he could more persuasively impersonate a man on a civilizing mission.” This seems unnecessarily harsh. Surrounded by men like Henry Adams who favored the Russians, and much loose talk about the “Yellow Peril,” Roosevelt saw in the Japanese an upstart nation standing up to a bullying neighbor.

Similarly, Lears devotes a single sentence to Roosevelt’s truly extraordinary exertions in favor of federal protection of wilderness lands, which he calls “TR’s greatest and most lasting achievement.” He ascribes the “main strength” of the legislation that gave us the National Parks and National Forests, placing roughly 230 million acres under federal protection, not to Roosevelt’s decisive advocacy, however, but rather to “popular longings for revitalization through wilderness experience.” “With the frontier officially closed,” he maintains, “upper-class men constructed an ideal wild nature as a backdrop, a challenge, and a foil for masculine struggle.” Even amid this “emerging wilderness cult,” Roosevelt is seen to come up short, with his “domesticated wilderness of Adirondack guides” and the “absurdity” of his African safaris. One could argue that it was Roosevelt himself, however, in his well-publicized exploits as a rancher in the Badlands and hunter in the Adirondacks, who did much to inspire these popular longings for wilderness preservation, not to mention the federal muscle he exercised to fulfill them.

Lears underestimates in this regard what one might call Roosevelt’s vitality as a public performer. One of Lears’s major assumptions is that Americans during the Gilded Age sought opportunities for escape from the increased tedium and regimentation of the workplace. “Sensing a subtle imprisonment, they harbored fantasies of escape.” He has surprisingly little to say about the pervasive escapist theme of “passing” in the popular literature of the period, as black characters passed for white (in, for example, James Weldon Johnson’s Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man ), Jews passed for Gentiles, rich passed for poor, and, in the novels of Jack London, dogs passed for wolves and vice versa. Instead, Lears has persuaded himself that the “escape artist” Harry Houdini, a Jewish immigrant whose real name was Ehrich Weiss, was the perfect hero for spectators longing to escape from “a claustrophobic age.”

One could argue with equal plausibility that it was TR himself, with all his bluster and bravado, who was the supreme American performer of the age. Americans eager for imaginative escape could find it in their swashbuckling president, with his dramatic speeches, his cinematic cavalry escapades, and his theatrical forays into the wilds in search not only of bear but moments of exaltation in nature. Hofstadter notes that Roosevelt’s “talents as a comedian were by no means slight.” If Americans often felt trapped in their tedious routines, Roosevelt, “with his variety and exuberance and his perpetual air of expectation, restored the consciousness of other ends that made life worth living.”3

4.

“Is Life Worth Living?” happened to be the title of a speech that William James, who succumbed periodically to bouts of lethargy and depression, gave in 1895. Casting about for reasons to engage in daily existence that often seemed devoid of zest and challenge, he resorted to the military metaphors of the age:

If this life be not a real fight, in which something is eternally gained for the universe by success, it is no better than a game of private theatricals from which one may withdraw at will. But it feels like a real fight—as if there were something really wild in the universe which we, with all our idealities and faithfulnesses, are needed to redeem.

This is movingly stated, especially the arresting phrase about “something really wild.” But Lears, detecting a worrisome symptom in James’s combative rhetoric, wonders why life has to be “a real fight” to make it worth living. Why did Americans continue to insist, even as the evidence mounted of the horrors of armed combat, on martial heroism as the true measure of the value of life?

Throughout Rebirth of a Nation, Lears reserves his highest praise for those who favored nonintervention over military engagement. He quotes approvingly Mark Twain’s antiheroic assessment of war, based on his own brief service in a Confederate militia, as “the killing of strangers against whom you feel no personal animosity: strangers whom, in other circumstances, you would help if you found them in trouble, and who would help you if you needed it.” Lears sees no convincing reason for American participation in World War I. “One did not have to be a sentimental pacifist to see this.” He concedes that World War II was a “justifiable war,” perhaps not quite the same thing as a justified one. Here again, one feels the pressure of recent events, and in particular how the attacks of September 11, as Lears puts it, “brought militarism back with a vengeance, providing the idea of regenerative war with a luster it had not enjoyed (outside Fascist circles) for nearly a century.”

During the closing pages of his book, Lears moves ever closer to a pacifist position, always differentiating it from a merely “sentimental” opposition to war. He seems, in this regard, to fear the kinds of criticism that Theodore Roosevelt and his strenuous crew would level at pacifists of all stripes.4 Lears ends Rebirth of a Nation with a scene not from the historical record but from Pat Barker’s World War I novel The Ghost Road, in which a grievously wounded veteran of trench warfare with much of his jaw blown off, under the care of the neurologist W.H.R. Rivers, repeats something that sounds like “Shotvarfet” and turns out to be “It’s not worth it,” a cry taken up by other wounded men in the ward. Lears comments:

Amid the official language of war, then and now, it is worth recalling that darkened ward of broken men and their dark, insistent truth. They remind us that sometimes a pacifist stance is the least sentimental of all, the most thoroughly embedded in the viscera of experience.

This Issue

January 14, 2010

-

1

These overlapping “ages” do not coincide exactly. Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence (1920) is set in New York and Newport during the 1870s; Richard Hofstadter’s The Age of Reform (1955) extends from 1890 to 1940; Lewis Mumford’s The Brown Decades (1931) is a study of the arts in America from 1865 to 1895. While the Gilded Age is generally considered to begin after the Civil War, there is less agreement about when it ended. Some date it to the “closing” of the American frontier during the 1890s while others see Theodore Roosevelt’s efforts to regulate trusts, beginning in 1902, as inaugurating a “Progressive Era” in American politics. Jackson Lears, in the book under review, sees more continuity than change during the period from 1877 to 1920.

↩ -

2

See Adam Nagourney and Michael Cooper, “McCain’s Conservative Model? Roosevelt (Theodore, That Is),” The New York Times, July 13, 2008.

↩ -

3

Stuart Sherman’s suggestion, as summarized by Richard Hofstadter in The American Political Tradition (Knopf, 1948), p. 208.

↩ -

4

Having grown up in a Quaker family, I can say that I’ve met very few sentimental pacifists in the Society of Friends. They are, for the most part, fierce and pragmatic in their opposition to war.

↩