Not long after takeoff from LaGuardia last January 15, as the Charlotte-bound US Airways flight was climbing out smoothly over the Bronx on a northerly heading, something hit the airplane. Something that seemed big. There was a loud noise and a collective gasp from the passengers. Some of them had seen something like a flash of brown going into the engines. The airplane began to wiggle a little and decelerate. The flight attendants were still strapped in their seats not near any windows, but they guessed what had happened. There was a smell of something burning. It had become completely quiet. There was no word from the cockpit. A woman would text her husband, “My flight is crashing.”

The airplane was not crashing, but it was definitely headed down. At about 2,500 feet it had collided with a flock of Canada geese flying southwest; geese are not uncommon in the New York area, their ancient migratory routes passing over it. At least five birds had hit the plane, three or more going into and virtually destroying both engines. The copilot, Jeffrey Skiles, had been at the controls, and he and the pilot, Chesley Sullenberger, had suddenly seen, at the same time, the flock of geese slightly above and ahead.

“Birds!” Sullenberger cried just before they hit.

“Whoa!” Skiles said.

They were fortunate that a bird—Canada geese are large—hadn’t crashed directly into the windshield, but the engines were already banging and winding down. Fire was coming from both of them, flames from one and fireballs from the other. Briefly, for some fifteen seconds, Sullenberger tried to restart the engines and also, more or less instinctively since it was not part of the procedure, he started an auxiliary power unit in the tail to maintain electrical power. His pulse rate must have been high, but he said calmly, “My aircraft,” and took over the controls.

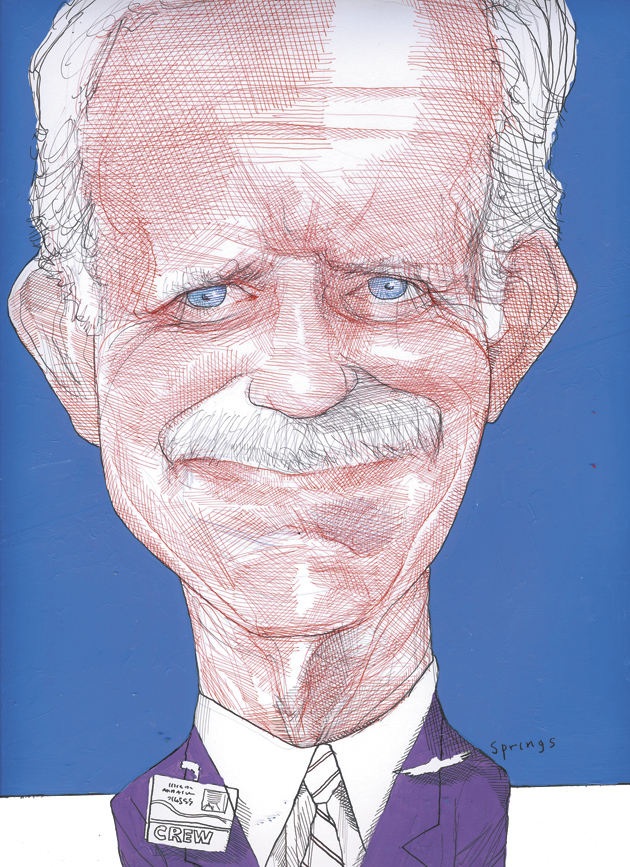

Sullenberger was almost fifty-eight years old, an experienced and steady captain who had been flying since he was sixteen. He had learned to fly in high school in Denison, Texas, from a grass field and had gone on to the Air Force Academy and the beginnings of a career as a fighter pilot, during which he had flown a Vietnam-era fighter, the F-4 Phantom. He had never, in his long flying career, had an engine failure. It was hardly surprising since jet engines are simple in design and extremely reliable although subject to damage if anything reasonably substantial comes into the intake. He called New York Approach and said, “We lost thrust in both engines. We’re turning back towards LaGuardia.”

As Sullenberger began a turn to the left to return to the field, Skiles began working on the checklist of air restarting procedures. They had slowed to a recommended gliding speed. In the cabin no one knew what was happening, although knowledgeable passengers could see that they were turning back and had some idea of the situation.

The pleasures of air travel, such as they once were, have long since vanished, the result of airline deregulation and the fierce competition that followed, along with the inconveniences of guarding against terrorism. Airline pilots and even flight attendants have seen their pay and prestige inexorably decline over the years.

Of the people to whom you almost blindly entrust your life—surgeons and pilots come to mind—you may get some idea of a surgeon through references, former patients, affiliations, and perhaps from your own impressions during a consultation, but an airline pilot is a remote and unknown figure. He or she is, depending on the country and category of operator, presumably well-trained and capable, but there are, as William Langewiesche points out, more than 300,000 airline pilots in the world, not all of equal experience or ability. There is a low end and a high end and probably a bell curve. From the operating table you can only fall a few feet at the most or gently pass from profound sleep into oblivion, never knowing the difference. In an airplane, though statistically safer than in a car, you are existentially on the edge, and a mischance can send scores or even hundreds of terrified, otherwise unrelated people, as if in The Bridge of San Luis Rey, smashing into the ground. Or water.

Sullenberger had been quickly offered Runway 13 to land on at LaGuardia. He was just descending through 1,900 feet, and the field was still out of sight to the left. He was a precise, mature pilot. At this already crucial point he had two tasks and just one decision. The tasks were, first, to get one or both engines restarted. If he was successful, that would solve things. If not, or in any case, he had to land the airplane someplace. The question was: where? Runway 13 was seven thousand feet long. In a case like this, you might prefer ten thousand feet, but of equal importance was that the water of Flushing Bay came right to the threshold of the runway, there was no overrun or stretch of grass if you hit short. So it would have to work out almost perfectly. It was too risky. He called and said, regarding the offer of the runway, “We’re unable. We may end up in the Hudson.”

Advertisement

There are emergencies that come about slowly, with time to weigh all options—running low on fuel, for example—and emergencies that arrive suddenly, within seconds sometimes. What makes in-flight emergencies different is that the airplane cannot be parked in order to figure things out. Circumstances can be such as to cause confusion and even panic. In primary training, at the time when I went through it, a check flight was certain to include, although it was meant to be a surprise, the throttle being suddenly jerked back to idle and the check pilot announcing, “Forced landing.” You had to look around, quickly judge alternatives, and, adjusting your course and glide, head for the best of them. The forced landing drill would almost never be given just after takeoff, since there was heavy traffic around the field, and we had no radios in the planes.

Fly by Wire is a story with two heroes, one of them the pilot of the stricken plane, and the other the man who had been responsible for the advanced control concepts of the airplane itself, an Airbus A320. This is Bernard Ziegler, the impressive engineer and pilot now in his late seventies and retired, who envisioned, championed, and oversaw the entire generation of airplanes for Airbus, and whose portrait is masterfully drawn. Langewiesche is a pilot himself and has written with an intimacy about flying.* A good portion of Fly by Wire is given over to the Airbus A320, its characteristics, and its excellent design. Cables or hydraulic lines to the control surfaces in airplanes had long since been replaced by electric wires and small motors. The addition of digital computers created what is known as fly-by-wire. It is not a robotic system; the pilot is still in control, although in the A320 the computers have been given great authority. Essentially they prevent the pilot from flying the airplane hazardously. They limit angles of bank and elevation and are programmed to prevent stalls by precisely trading off angle of attack and airspeed and even automatically increasing power if required. A good pilot can do this but perhaps not as invariably or finely as the computer. A less good pilot is definitely made safer.

This is not to say that the airplane cannot crash. The Air France Flight 447 out of Brazil that crashed in the Atlantic last June with 228 people aboard—the cause still unknown—was an Airbus 330. In 1988 one of the first A320s, with 136 passengers aboard, some of whom had never flown before, was part of an unforgettable air show at a small field near Mulhouse in France. The passengers did not know they were taking part in a show; they mainly knew that they would be circling Mont Blanc on the flight.

The pilot was an Airbus convert and enthusiast, forty-four years old with thousands of flying hours and an excellent reputation. There were to be two passes over the field, the first slow and the second at speed. The minimum altitude was to be one hundred feet. There were 15,000 spectators. You can see a film of it all on YouTube: Mulhouse, Airbus A320, mislabeled “during take-off.” The airplane, wheels down, full flaps, nose high on the very edge of a stall, flies serenely along barely thirty feet above the ground. The pilot had disengaged the automatic throttle advancement, which presumably one should not be able to do, in order to hold the plane on the very knife edge a second or two longer than the computers would allow, and then to shove the throttles forward himself. He did it too late. The airplane, refusing to stall but without the power it needed to go higher, plowed into the trees, first the tail and then gradually, as if drawn into the forest, the rest:

For the air show spectators, the sight was surreal. First the airplane sailed by them almost within reach, with some announcer finding things to say. Then they watched it sail away and, without the slightest urgency, continue smoothly into the trees. Lifted by its wings, and still largely under control, it sank slowly from sight with its nose held high, until only the nose was visible moving forward through the forest like the head of a swimmer refusing to drown.

A great burst of flame marks the end. Actions of the flight attendants saved almost all lives. Langewiesche’s descriptions of accidents in addition to this one are particularly dramatic and convincing. Accident reports are frequently like legal documents or autopsies, but, without being sensational, he makes them compelling.

Advertisement

Sullenberger, in his Airbus A320, continued with Skiles to try to restart the engines, and amid unnecessary and irrelevant voice alarms going off in the cockpit, continued talking to the controller. Teterboro, an airport off to the right in New Jersey and no closer than LaGuardia, was briefly considered, but, like Newark, rejected. The decision had really been made. The best choice was the Hudson.

Ditching is best done with power. The general assumption is that the airplane will be going down in the ocean somewhere, perhaps in a bay. With its landing gear up and at close to normal touchdown speed, the airplane is flown parallel to any waves and between them, and the aft section is the first to come into contact with the water. There have been only a few airliner ditchings and apparently only one without power, in Java, just seven years before Sullenberger’s. That plane also ditched into a river (and one person, a flight attendant, died).

The need for power is obvious: the pilot wants to be in complete control of the descent, holding it off just above a stall and allowing the tail to touch and then smoothly setting the rest of the fuselage down like a boat launched at more than a hundred miles an hour. The only ditching I know about personally—they were, of course, commonplace during World War II—happened just off Oahu in August 1947. I was a lieutenant in a Troop Carrier squadron, and we were awakened in the middle of the night to help search for a B-17 carrying the US ambassador to Japan that had gone down only an hour or so earlier.

The B-17 was from MacArthur’s flight section in Tokyo and was on the way to Washington, D.C., with the ambassador, who was carrying the draft of the US–Japanese peace treaty in a lead-weighted briefcase. Crossing the Pacific in those days was done in long, slow stages, stopping to refuel at Guam, Kwajalein, and Oahu. It turned out that the refueling at Kwajalein had been careless, the gas tanks had not been “sticked”—their contents visually checked with a calibrated stick, the normal procedure—and the gauges on the instrument panel, more trustworthy in the lower ranges, had suddenly gone down when the airplane was between Johnston Island and Oahu, showing not enough fuel to reach either. The pilot, hoping against hope that they were wrong, continued until one by one the engines quit.

The navigator of the flight, whom I knew, said that they sat listening as the engines went silent and then started down, the altimeter slowly and hesitantly unwinding. The lights were on in the main cabin that had been fitted up for travel, and the plane’s landing lights were on. In their brightness, as they neared the water, the large black swells of the ocean could be seen. The plane started into a trough but then the wingtip hit a wave and, lights still on, as in the Titanic, the plane started up in a big cartwheel. They could hear the rivets singing as they tore from the metal of the wing, the navigator said, and over the plane went, plunging into darkness. He survived, in a life vest, floating with some others in the ocean until the next day, but the ambassador, George Atcheson, and the draft treaty did not.

Sullenberger’s first announcement to the cabin, when the die had been cast and they were going to end up in the river, was “This is the captain. Brace for impact.” Although three and a half minutes, the time that elapsed between hitting the geese and landing in the river, seems leisurely enough—a man can run close to a mile in that length of time—the pair in the cockpit were too occupied to explain, even in the briefest terms, what was going on.

The order came as a surprise to nearly everyone. One man said out loud, “What does that mean?” Soon enough he figured it out…. The most astute passengers had known for a while that they were descending over the Hudson, and would not be returning to LaGuardia, but some had held out hope that they were headed for Newark instead. Now they knew that the airplane was going to crash into the river. The flight attendants did not know it, because…they had no eye-level windows while seated in their positions, and were expected to rely on instructions from the cockpit…. They therefore reacted purely by rote, chanting, “Brace! Brace! Heads down! Stay down!” with no idea of how high they were, where they were, or what was going on.

A man in the back had the poise and presence of mind to call out, “Exit row people, get ready!” A woman mid-plane with a baby boy on her lap did not know what to do. The man next to her asked if he could brace her son for her, and she passed the child to him, and he did.

In the cockpit the ground warning alarm had begun, an automatic voice repeating that the plane was too low. Sullenberger called for the flaps on the wings to be extended in order to slow the plane for impact. At two hundred feet he began breaking his glide and ballooned a little. They were at 150 knots—about 180 miles an hour. He lowered the nose slightly and then, pulling back on the stick in the last few seconds before touching down, his airspeed spent, remarked coolly to Skiles, “Got any ideas?”

“Actually not,” Skiles said.

They touched the water at an optimum angle, nose slightly high, 120 knots. The left engine tore away, the plane’s belly ripped open toward the rear, and the aircraft skimmed to a stop. There was such heavy spray that the passengers near the windows thought they had gone entirely underwater.

The evacuation of the plane was all one could hope for. Water entered quickly. There was an eighty-five-year-old woman who needed a walker, plus several children aboard. In the rear, the floor had buckled and a beam had broken through. There was more water there; it rose to almost chest-high before everyone was out. The flight had been sold out—only one empty seat. The flight attendants, three women all in their fifties, were exemplary. Doreen Welsh, the oldest, in the rear, had the greatest difficulties and was seriously injured. People tried to swim in the river, some slipped into the water and were pulled back, all ended up standing on the wings, some waist deep in water, or in the inflated slides and rafts. Sullenberger and Skiles had all along been moving through the cabin assisting and handing out life vests. In the end Sullenberger went through the deep water in the cabin one last time to make certain no one was left. The water was bone-chillingly cold, but within five minutes the first of the rescue boats was at the plane. There had been no casualties. All survived.

Chesley Sullenberger and his entire crew had performed admirably. The event was so spectacular, in full view of Manhattan and the New Jersey side of the Hudson, and it ended so happily that the public embraced it. It seemed a miracle, and Sullenberger, decent, conscientious, serious, was a hero. It was a life-changing event, he said in an interview, not only for himself but for everyone on the airplane and their families. It was also true that some of his passengers, having been rescued, simply went back to LaGuardia and caught a later plane, just as at Mulhouse twenty of the passengers had simply walked from the burning wreckage through the forest to the autoroute and hitchhiked home.

A “miracle.” On examination it seems more like a bit of luck and a job perfectly done. Airline crashes normally produce so many fatalities that this was an unexpectedly nice outcome. Whether the computerized characteristics of the A320 were an important element in that outcome seems uncertain. Langewiesche gives the airplane credit for smoothing out the slight ballooning in the last moments and easing it in the optimum position onto the water as Sullenberger held the stick full back, but given Sullenberger’s abilities and good judgment, along with the weather and other circumstances, it seems likely that he would have accomplished the same thing in a Boeing, and that no autopilot or computer we can conceive of could have handled the emergency half as well.

This Issue

January 14, 2010

-

*

See James Fallows’s review in these pages of Langewiesche’s Inside the Sky: A Meditation on Flight (Pantheon, 1998), January 14, 1999.

↩