1.

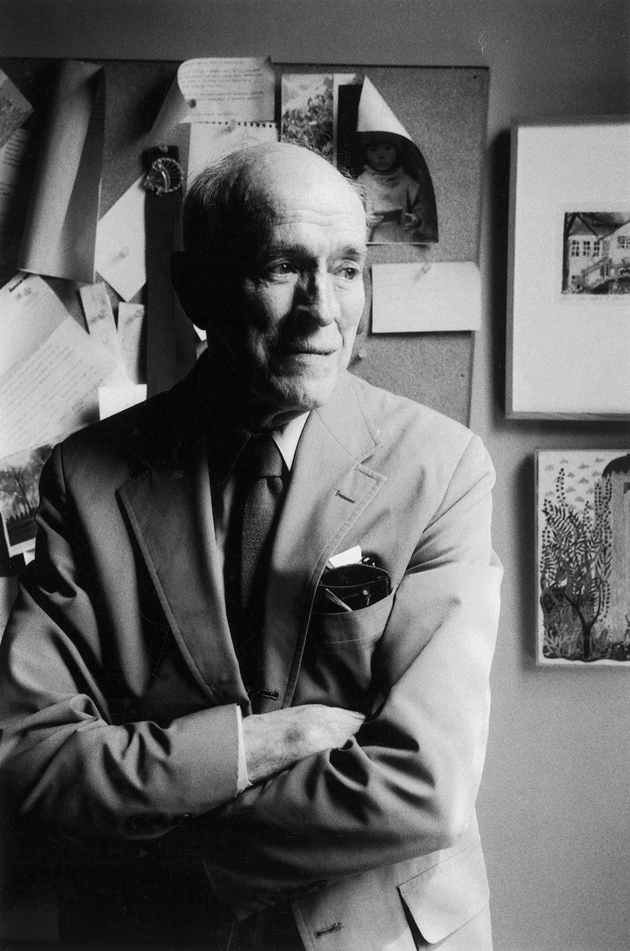

William Maxwell was a plain-speaking, seemingly realistic novelist who wrote autobiographical stories about middle-class life in small towns and urban neighborhoods. At first he tried to imitate Virginia Woolf’s lyricism, but he soon cleansed his style of ornament and exaggeration. He wrote in taut, laconic rhythms that evoked the spare speech of his native Midwest, and portrayed his characters’ inner and outer lives with economical clarity and nuance. His props and characters were indistinguishable from real settings and persons from Lincoln, Illinois, where he was born in 1908, and Manhattan, where he lived most of his adult life until his death in 2000. Almost every episode in his fiction was reconstructed from events in his life, rearranged for concision and elegance. In a few heightened moments in his novels and stories, he imagined what the furniture and fixtures in a room might say if they could speak among themselves, unheard by human ears, but he presented these moments as metaphors for the sad reality of human moods.

Maxwell had two separate careers as a writer; both overlapped his third career as fiction editor of The New Yorker. His first career, as a writer of realistic novels and stories, began when his first novel appeared in 1934 and continued in such books as The Château (1961) and So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980). In 1946, a year after he married a young painter, he began a second career as a writer of magical folktales in the style of Mother Goose and the Brothers Grimm. In these tales the magic hidden beneath the surface of his realistic fiction emerges with explicit and often comic force, and their world is partly the familiar modern one, partly a timeless fairyland, and wholly his own invention.

“Once upon a time,” these tales typically begin. Then a talking bird transforms a woman’s life; or a family of aristocratic English moles, fleeing modern construction, burrows through the earth to China; or a country exists where all children are born wearing masks that they shed every year; or an angry toad curses a child by making her hate her parents. In Maxwell’s realistic fiction no one learns and no one changes. In his folktales, a queen spends a lifetime learning humility and love; a man who tries to be left alone learns to be treasured by many friends.

Maxwell called these tales “improvisations.” Many began as stories he told to his wife in bed at night; she sometimes shook him awake to ask what happened next. At first he thought they were not worth publishing. Then he had some of them printed in limited editions, little magazines, and eventually in the back of The New Yorker. The one book-length critical study of his work, Barbara Burkhardt’s William Maxwell: A Literary Life (2005), passes over them in half a paragraph, but they are his most complex and moving works, the ones nearest the heart of his imagination.

In both art and life Maxwell’s plain style was a mask over a sensibility that had less in common with such chastened realists as his friend John Cheever than with would-be magicians such as W.B. Yeats, whose phrases Maxwell threaded into all his work. The world of his serious fiction looks like the real one, but the ways in which things happen there—the invisible connections between events—are exotic and unreal, driven by primitive magic and unseen forces, sometimes generous, usually malevolent.

More than any other American writer, Maxwell became the object of a cult of admirers who thought of themselves as a “magic circle”1 with Maxwell and his wife at the center; the closest parallels are the cults that gathered around the late-Romantic artist-heroes Stefan George and D.H. Lawrence. Among his circle Maxwell excited “a kind of astonishment” and “a kind of wonderment”—phrases used by the coeditors of a book of memoirs, A William Maxwell Portrait (2004). These editors also write: “There seems to have been almost no one like him in his own time in American letters, perhaps ever.” Almost everyone who remembers Maxwell writes about his gentleness and courtesy, and about the extraordinary gifts he made of time, money, and attention.

Maxwell alone seems to have known how different he was from the saintly image that astonished his friends. He never deluded them. He went out of his way to keep no secrets. In the self-portraits he wove into his serious fiction he is someone who “wants to be liked by everybody,” someone who, with deliberate calculation, “lets the other person know,…by the sympathetic look in his brown eyes, that he wants to know everything.” He gives the forms of friendship, not its substance, because he wants company: “The landscape must have figures in it.” In an overtly autobiographical story—about a man who lives, as Maxwell did, with his wife and daughters on the Upper East Side of Manhattan—he wrote:

Advertisement

There was a fatal flaw in his character: Nobody was ever as real to him as he was to himself. If people knew how little he cared whether they lived or died, they wouldn’t want to have anything to do with him.

And in a late story with the pointed title “What He Was Like,” a daughter reads her dead father’s diaries and tells her husband:

He wasn’t the person I thought he was. He had all sorts of secret desires. A lot of it is very dirty. And some of it is more unkind than I would have believed possible. And just not like him—except that it was him.

Maxwell’s friends, seduced by the flattering sense they got from him and his wife that “you were the most interesting, attractive person they had ever met,” overlooked everything his fictional self-portraits confessed. Almost every memoir about him includes some variant of the awed and grateful declaration “I was one of the circle.”

“Saintly” is a word that recurs in everything written about Maxwell and his work. But in the same way that his friends ignored the primitive, amoral magic that governs the realistic- looking world of his fiction, they ignored his contempt for any ethical understanding of life—any way of thinking in which actions have consequences, and events are the outcome of human choice, not of arbitrary, impersonal forces. For those inside his circle, Maxwell’s magic brought benediction and comfort, but magic is an instrument of power. John Cheever wrote: “It seemed that he was a man who mistook power for love.” A few of his friends were uneasily aware that the magic circle had a guarded perimeter, that its magic was benign only to those allowed inside. One memoir notices Maxwell’s “flintiness” to the excluded, but calls it justified: “I never knew him to be unreasonably cold.”

Maxwell’s realistic fiction comprises six novels and sixty stories. He also wrote forty or more of his folktale “improvisations.” His nonfiction includes Ancestors: A Family History (1972), about his Presbyterian forebears in Scotland and America, and The Outermost Dream (1989), a selection of essays. The Library of America’s two-volume edition collects all his novels, two thirds of his stories, and most of his improvisations. It also reprints eight brief essays that he wrote about his own work, but omits the rest of his nonfiction.

The editor, Christopher Carduff, doesn’t name the stories he leaves out, but most can be tracked down in indexes to The New Yorker.2 One omitted story, “The News of the Week in Review” (1964), is an acid portrait of a neighbor in Westchester, where Maxwell had a country house. He published the story under the name Gifford Brown, a pseudonym he used when he didn’t want neighbors or relatives to notice the unpleasant things he was writing about them. The secular saint portrayed by Maxwell’s friends could never have written it, but the real Maxwell did.

2.

Maxwell’s father, who worked for an insurance company, appears throughout his serious fiction with only slight changes from Maxwell’s memories of him as blunt and remote. Maxwell’s older brother lost a leg in a childhood accident but remained athletic and boisterous—one of Maxwell’s pseudonymous stories portrays him as a racist boor—while Maxwell himself remained fragile and bookish. When Maxwell was six a young teacher’s assistant walked him to and from kindergarten and sang to his father’s piano accompaniment at the family’s musical evenings at home. Maxwell’s mother died in the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918–1919, two days after bearing a third son. He was ten years old. “The worst that could happen had happened,” he wrote later, “and the shine went out of everything.” All his work is shadowed by her death, which he seems to have experienced less as an event in his personal history than as a condition of the world, like the Fall of Man.

Not quite three years after his mother’s death, his father married the teacher’s assistant. A year and a half later the family moved from Lincoln to Chicago. “I was removed from Lincoln at the age of fourteen,” Maxwell said, “and so my childhood and early youth were encapsulated so to speak, in a changeless world.” He overcame his loss by writing down his memories and preserving them from change:

I have a melancholy feeling that all human experience goes down the drain, or to put it more politely, ends in oblivion, except when somebody records some part of his own experience…. In a very small way I have fought this, by trying to recreate in a form that I hoped would have some degree of permanence the character and lives of people I have known and loved.

In high school he became passionate about art and literature. One summer, doing chores at an artists’ colony in Wisconsin, he was befriended by the playwright and novelist Zona Gale, who gave him maternal literary advice. At the University of Illinois a teacher handed him the newly published To the Lighthouse; for the rest of his life he both adulated Virginia Woolf and rebelled against her influence. He planned to get a Ph.D. and become an English professor, but a bad grade in German ended his graduate school fellowship and sent him into freelance work.

Advertisement

He was twenty-five when he wrote his first novel, Bright Center of Heaven (1934). Years later he refused to reissue it, calling it derivative and, in its mixture of lyricism and cleverness, “stuck fast in its period.” These are precisely its charms. The book is an insouciant American fantasia on the first section of To the Lighthouse. Mrs. Ramsay presiding over the assorted guests in her summer house in Scotland becomes the motherly Mrs. West at her Wisconsin farm that doubles as an artist colony. The amateur painter Lily Briscoe is split into an eccentric young artist and a temperamental pianist. In place of the timid couple who get engaged under Mrs. Ramsay’s influence, Maxwell’s young lovers are an actress and a college teacher who reads Yeats to her and does not yet know she is pregnant. Mrs. Ramsay’s triumphant boeuf en daube is Americanized into Mrs. West’s picnic interrupted by rain.

In To the Lighthouse the Ramsays’ summer idyll is followed by sudden death and a world war. In Bright Center of Heaven the world of injustice and death arrives in the person of Jefferson Carter, a black lecturer on social themes who is annoyed with himself for accepting Mrs. West’s hospitality when he ought to be campaigning against the judicial lynching of the Scottsboro Boys. Before the day is out, he takes offense at a remark that may or may not have been racist, and leaves.

Race prejudice is a recurring theme in Maxwell’s work, and he later thought he had mishandled it in his melodramatic treatment of Jefferson Carter. But the point of the episode was that a magic circle devoted to art and beauty always closes itself off against harsh realities. This was a truth that Maxwell seemed to forget when he and his wife had a magic circle of their own.

Bright Center of Heaven leaves almost all its story lines unresolved, and the future remains open for all its characters. (After reading the manuscript, Zona Gale wondered whether she had misplaced the final chapter.) All of Maxwell’s later novels, in contrast, end in visions of stasis, futility, and helplessness. Their characters have all the attributes of real persons except one: they have no future.

Maxwell’s second novel, They Came Like Swallows (1937), is based on his mother’s last weeks at home and her fatal illness in a maternity ward. The title is a fragment from Yeats’s “Coole Park, 1929,” a poem about an older woman’s power to shape and focus everything around her. The story is told from the points of view of Maxwell himself (portrayed as two years younger than he was) and his older brother. The older brother is convinced that their mother died because he forgot to keep her out of the room where the younger brother was in bed with flu. Later someone explains that this could not have caused her death, because she contracted the disease many weeks later. Things happen as they do because life is inherently tragic, not as the effect of human acts. The brother imagines a plot—a connected sequence of events—where there is only a story.

All of Maxwell’s novels have a story but no plot. A plot is the means by which fiction portrays the consequences of actions, but it is not like a pool table; one event never mechanically causes another. In a plot each event provokes other events by making it possible for them to happen—possible but not inevitable, because human beings are always free to choose their response to provocation. Maxwell succumbed to an error common among writers who, as he did, organize their work for the finest possible rhythms and textures: the error of thinking of plot as mechanical and therefore trivial. As he explained to John Updike: “Plot, shmot.”3

Maxwell continued his life story in The Folded Leaf (1945), a novel about adolescence. The sensitive Lymie Peters becomes passionately attached to an athlete in high school. Then, after both go on to the same college, Lymie falls shyly in love with a literary young woman. When she and the athlete fall in love with each other, Lymie tries to kill himself by slashing his throat. The narrator alone knows that Lymie and his friends are doomed to live out patterns inherited from a remote past. Fraternity members at an initiation, for example, “were reenacting, without knowing it, a play from the most primitive time of man.”

Maxwell wrote this while he was being psychoanalyzed by Theodor Reik, a disciple of Freud with interests in anthropology and art. Reik believed that a writer’s work pointed toward the hidden potentialities of his life. Reading the manuscript of Maxwell’s novel, he found a bleak, hopeless final scene in which Lymie’s two lost loves visit him in hospital and play a childish game with their hands. Reik persuaded Maxwell to add something that would give Lymie a future. When the book appeared in print it had a new final chapter in which Lymie, revived by hope, plants flowers in the forest:

Although he didn’t realize it, he had left his childhood (or if not all, then the greater part of it) behind in the clearing. Watched over by tree spirits, guarded by Diana the huntress and the King of the Woods, it would be as safe as anything in the world.

It would never rise and defeat him again.

This was false to the rest of the book, but Reik cared more about Maxwell’s future than about his novels. For a paperback reprint in 1959 (reproduced in the Library of America edition) Maxwell restored the bleaker ending.

While he was in analysis, Maxwell met Emily Gilman Noyes and badgered her into marrying him. What he seems to have brought away from Reik was the relieved discovery that he was not doomed by his own hopelessness, that his despair over his mother’s death need not prevent him from becoming gregarious, generous, and sympathetic. This was perhaps not what Reik had hoped to give him. Some of his later novels and stories portray a man who convinces a woman to marry him and then cannot give her the love she desires. The only life and love that were real to him remained locked in his memory of his first ten years.

3.

Time Will Darken It (1948), Maxwell’s fourth novel, is an autobiographical fantasy. Set in 1912, it portrays what should have happened but didn’t in 1918–1919 when his mother died. Austin King—Maxwell’s father, reimagined as a lawyer like Maxwell’s grandfather—has a four-year-old daughter (Maxwell was four in 1912) and his wife is pregnant with their second child. A visiting cousin’s daughter stays to found a kindergarten and neurotically throws herself at Austin King. In real life, Maxwell’s mother died after giving birth, and his father courted and married the kindergarten teacher’s assistant. In the novel, the mother survives a difficult childbirth and Austin King is appalled by the young teacher’s approaches. In the end the teacher (like one of Maxwell’s aunts) stupidly throws kerosene on a smoldering fire, and leaves town scarred and humiliated. The mother is irritated with the father but the family stays intact. Maxwell said he learned from a dream how the novel should end, and its sepia-toned realism masks a child’s magical fantasy of vengeance.

Maxwell and his wife made a four-month visit to France in 1948, and he spent the next dozen years trying to write a novel about it. Until shortly before publication, The Château (1961) was a leisurely story about an American couple baffled by the character and history of the landlady and guests in the château where they have rented a room. The mostly realistic narrative is interrupted by moments when the style turns magical while the actual events remain plausible. The furniture expresses its feelings:

Oh heartbreaking—what happens to children, said the fruitwood armoire…. The dressing table, modern, with its triple way of viewing things, said: It is their own doing and redoing and undoing.

In one harrowing extended episode, the furniture and the characters join in a silent ensemble:

“My likeness is here among the others,” the boy in the photograph said….

“The house is cold and damp and depressing,” Barbara Rhodes’s reflection said to the reflection of M. Carrère.4

Maxwell left unresolved all the mysteries that puzzle the American couple. How, for example, did their aristocratic landlady lose her husband and her money? Maxwell’s friend Francis Steegmuller, reading the manuscript to correct Maxwell’s French, kept demanding explanations, so Maxwell added an epilogue in the form of a dialogue between the narrator and a reader, in which he waves away the reader’s request for the missing links of a coherent plot: “I don’t know that any of those things very much matters,” the narrator says. “They are details. You don’t enjoy drawing your own conclusions about them?” As a sop to the reader, the narrator explains away the landlady’s mystery with a melodramatic plot summary that reads like a parody of Balzac. The epilogue answers the reader’s questions by insulting him for having asked them.

In the years when he was writing this book Maxwell began to attract his magic circle of admirers, and began to express his faith that writing—the imaginative art of memory—is the highest of all callings. His friends were speaking literally when they recalled that “his religion had been literature” or that, to him, “writing” and “his god…were the same thing.”

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the religion of art was effectively a High Church movement, favoring esoteric doctrines and ornamental, ritualistic styles. By his example, and through his influence on the writers he edited at The New Yorker, Maxwell founded a Low Church movement with a laconic style and a bleak dogma of hopelessness. Maxwell’s friends make vague, veiled allusions to the emotional price his wife and daughters paid for his ascetic devotion to art. “Nevertheless,” one says,

he was unrepentant when he confronted this aspect of his life…. “If I had to do it all over again I don’t suppose I would change anything. The writer in me would say, how dare you?”

The writer in him demanded absolute devotion. His older daughter recalls that he told her, without irony: “I want you to stay home and take care of me. I want you not to get married, and if you try to get married, I will try to undercut it so it doesn’t work.”5

Among his circle Maxwell spoke of himself in messianic pronouncements. “I grieve for everybody who was ever born,” he wrote to one friend. He said to another: “I saw people all around me, saw what they were like, understood what they were going through, and without waiting for them to love me, loved them.” The New Yorker writer Alec Wilkinson, in his mostly worshipful memoir, My Mentor: A Young Man’s Friendship with William Maxwell (2002), was only twice disappointed by him: once over a trivial matter, once because Maxwell had nothing to say when he begged for advice about his failing marriage and his love for another woman. “I knew only that I had asked for help and that he had refused to consider the matter.”

But Maxwell had no hidden wisdom that he was holding back. He was incapable of thinking about erotic and moral choices for the same reason he was contemptuous about plot: he cared about art and the past, not about choices that might shape the future. “The best thing I can do for you is listen,” he once told Wilkinson.

Maxwell’s last and shortest novel, So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980), is the summa theologica of his religion of art. Its story recreates the forgotten events that occurred in Lincoln, Illinois, in 1921, when a husband killed his wife’s lover and himself. Before the killings, Maxwell had been casually friendly with the killer’s son, whom he calls Cletus Smith. A few years later, in his Chicago high school, Maxwell was surprised to see Cletus in a hallway, but passed by silently, and never saw him again.

Now, a half-century afterward, he writes a novel about Cletus and the murders as “a roundabout, futile way of making amends” for his silence. He knows his gesture may be futile, but only a priest of the religion of art could even imagine making amends to someone by writing a novel about him. The priest of art summons his congregation to join him in conferring an imagined life on his lost friend:

The reader will also have to do a certain amount of imagining. He must imagine a deck of cards spread out face down on a table, and then he must turn one over, only it is not the eight of hearts or the jack of diamonds but a perfectly ordinary quarter of an hour out of Cletus’s past life.

Maxwell imagines this quarter-hour—and every other episode—with focused inwardness, and renders it in the dignified, conversational style he spent a lifetime perfecting. But his attention never strays from the transforming power of art. In playful moments he imagines what Cletus’s dog thinks about the story; in exalted ones he finds solace far from Illinois, in the Museum of Modern Art, where Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture The Palace at 4 A.M. evokes a vision of imaginative freedom:

In the Palace at 4 A.M. you walk from one room to the next by going through the walls. You don’t need to use the doorways. There is a door, but it is standing open, permanently. If you were to walk through it and didn’t like what was on the other side you could turn and come back to the place you started from. What is done can be undone. It is there that I find Cletus Smith.

So Long, See You Tomorrow is Maxwell’s most elegant and intricate novel, but its egoism and moral blindness leave an unpleasant taste.

Reviewers praised Maxwell’s fiction for what they called its “wisdom”—which is better understood as a child’s hopelessness expressed in an adult voice. Maxwell had a child’s shrewd perception of adult delusions (“People with no children have perfectionism to fall back on,” is one of many telling examples), and a child’s anxious knowledge of what is lost by growing up. But Maxwell’s serious work suffers from a child’s naive sense that adult life is a series of puzzlingly disconnected episodes, and a child’s ignorance of the ways in which an adult’s present moment is affected by both choice and circumstance, linked to a remembered past and a hoped-for future.

In Maxwell’s folktale improvisations, in contrast, his imagination is childlike, not childish, and these quick, deft fantasies shine with a sense of possibility and wonder unlike anything else in American fiction. In Maxwell’s serious writings, art is the salvation of life. In his improvisations, art is life’s lonely shadow. One of these improvisations, “A Fable Begotten of an Echo of a Line of Verse by W.B. Yeats,” tells the story of the “monument to Unaging Intellect” in a city marketplace. (In “Sailing to Byzantium” Yeats calls works of art “monuments of unageing intellect.”) For many years an old storyteller has been telling tales on the monument’s steps:

He had told so many stories with the recognition that the monument was at his back that he had come to have an affection for it. What he had no way of knowing was that the monument had come to have an affection for him.

The storyteller was never a great artist, and now he tends to lose the thread of his tales. But the monument, doomed to “an eternity of marble monumentality,” is grateful even for his fragmentary “once-upon-a-times.” One day, thinking no one is listening, he tells a tale about an old loving couple:

When the storyteller said, “From living together they had come to look alike,” the monument said, “Oh, it’s too much!” For there is no loneliness like the loneliness of Unaging Intellect.

The moral and emotional truths that Maxwell’s wise-sounding realistic novels studiously deny are the same truths that his wild and naive-sounding improvisations triumphantly and movingly affirm.

This Issue

April 29, 2010

-

1

Harriet O’Donovan Sheehy, “William Maxwell and Emily Maxwell,” The Guardian, August 26, 2000.

↩ -

2

The digital edition of The New Yorker, available online and in disk-based formats, contains the full contents of the magazine. The index identifies Maxwell as the author of his pseudonymous stories, but it is oddly incomplete, and fails to list some of his signed pieces. An almost full list may be found in Robert Owen Johnson’s An Index to Literature in the New Yorker (Scarecrow Press, four volumes, 1969–1976), listed under his own name and three pseudonyms: Jonathan Harrington, W.D. Mitchell, and Gifford Brown.

↩ -

3

John Updike, “Imperishable Maxwell,” The New Yorker, September 8, 2008.

↩ -

4

Silent dialogue was a technique Maxwell learned from Virginia Woolf. This exchange occurs in Between the Acts (1940):

↩ -

5

Interview with Jacki Lyden, All Things Considered, National Public Radio, August 24, 2008.

↩